Sight-Reading for Guitar by Chelsea Green is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Sight-Reading for Guitar by Chelsea Green is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The author, specialists at the Center for Learning & Teaching (American University in Cairo), and members of the Rebus Community have decided to launch this open series ahead of its full completion. We want to equip you with a quality open resource for teaching and learning by which you can successfully adjust to circumstances arising from the current COVID-19 health crisis and resultant physical distancing protocols.

We strive to complete the first edition of the series in the coming weeks to months. As a result, you can expect to see the following updates (to be recorded in the Version History):

Adapted from Christina Hendricks’ What is an Open Textbook

An open textbook is like a commercial textbook, except: it is publicly available online free of charge (and at low-cost in print), and it has an open license that allows others to reuse it, download and revise it, and redistribute it. This book has a Creative Commons Attribution license, which allows reuse, revision, and redistribution so long as the original creator is attributed. Additionally, most duets in the Let’s Play Compositions category have a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license, which bears an additional stipulation that the content may not be used for commercial purposes. This license was adopted in large part to credit the composers who generously contributed their duets to the series.

In addition to saving students money, an open textbook can be revised to be better contextualized to one’s own teaching. For example, in an open textbook one may add in examples more relevant to one’s own context or the topic of a course, or embedded slides, videos, or other resources. Note from the licensing information for this book that one must clarify in such cases that the book is an adaptation.

A number of commercial publishers offer relatively inexpensive digital textbooks (whether on their own or available through an access code that students must pay to purchase), but these may have certain limitations and other issues:

None of these is the case with open textbooks. In this open resource, Sight-Reading for Guitar: The Keep Going Method Book and Video Series, students can download materials in this series and keep it for as long as they wish. They can interact with it in multiple formats: on the web (YouTube lectures, PDFs, and streaming MP3s); MP3s; as a physical print book (coming soon), and more. Further, they can add notes and annotations via Hypothes.is.

See the Licensing & Attribution Information section for more information on what the open license on this book allows, and how to properly attribute the work when reusing, redistributing, or adapting.

“Chelsea Green is not just a wonderful performer but a born, deeply instinctual, and highly empathic teacher. Sight reading is a painful weak spot for not just beginners but for even high-level players (who do their best to avoid situations calling for it). Chelsea lays out a sounding plan in her “Keep Going Method” that offers an appealing path—challenging without being intimidating, substantial while full of fun. A great strength is the applicability to a wide range of levels and backgrounds. This made a pianist want to go out and buy a guitar.”

— Robert S. Winter, Distinguished Professor of Music Emeritus, UCLA; Creator of Music in the Air (first all-digital history of Western and world musics)

CLT Project Lead: Maha Bali

CLT Project Manager: Nadine Aboulmagd

Video Filming and Editing: Hassan Labib and Ahmad El Zorkani

Student Technology Assistants: Farida Harouni, Mennatallah Khalil, Abdel Rahman Diaa and Amr Adel Gouhar

Support: Tarek El Maghraby

Project Managers: Apurva Ashok and Zoe Wake Hyde

Susan Jones, Shehab M. Mohamed and Youmna Zakaraya

John Baboukis, Alan Berman, Alan Levine, Walter Marsh, Mark Popeney, Randy Rusk and Peter Yates

The original compositions were commissioned with grant funding from the American University in Cairo.

Frank Bartscheck, Philip Graulty, Mary Green, Jazz Hands, Karim Frège, Ahmed Hossam Refai, Mohamed Abou Rehab and Nick Romeliotis

Bahaa El Ansary, John Baboukis, Ashraf Fouad, Joan Greenwald, Eric Kiernowski, Paweł Kuźma, Walter Marsh, Brandon Mayer, Mark Popeney, Emile Porée, Felix Salazar and Peter Yates

The theoretical content, musical arrangements, compositions and guitar performances are by Chelsea Green (unless otherwise attributed).

Sight-Reading for Guitar: The Keep Going Method Book & Video Series teaches and trains guitarists from all musical backgrounds to understand, read and play modern staff notation in real time. Sight-reading is a juggling act. Good sight-reading demands that we see, understand, process and physically react to notation with speed and accuracy. If we linger too long on any mental, emotional or physical response, all the balls come tumbling down. This method imparts and reinforces the knowledge, skills, behaviors and attitudes needed to overcome sight-reading challenges in a fun and effective manner.

Sight-reading is especially difficult to master on the guitar, for a variety of reasons. Each reason is carefully addressed in this series. The first reason is due to the unique design of the instrument. The sight-reading guitarist must be able to: (A) play multiple pitches at the same time, (B) find multiple locations for the same pitch and (C) not look at her hands while reading notation.

The second reason has to do with attitude. Learning to sight-read can be emotionally uncomfortable. Since most guitarists learn to sight-read alone, they can mistakenly believe their frustration is a reason to quit. Bear in mind that all good sight-readers have experienced frustration. They are good at sight-reading, in large part, because they developed the right attitudes and behaviors to overcome discomfort.

The main obstacle, however, is that most guitar methods don’t emphasize the most important thing about sight-reading, which is to keep going. In order to develop the synthesis of seeing, understanding, processing and reacting to information in real time, students must train in playing to the end of the piece without stopping, regardless of mistakes and other distractions.

Beginning sight-readers learn quickly when paired with experienced sight-readers. This is why duets (songs for two instruments) are at the heart of this method. Every unit contains exercises and compositions with play-along duets. You, the student, will play the Guitar 1 part of the duet along with the recording. The recording contains the Guitar 2 part, which is played by the more experienced sight-reader. The recording will not stop playing when a mistake is made, which will inspire you to keep going.

The series consists of twenty-two units in total. It starts at a beginner level and progresses to an intermediate-advanced level. Each unit contains two sections: theoretical and practical. The theoretical section presents descriptions of musical symbols. This information can be learned from the video at the beginning of each unit, or from the written content directly below the video. Knowledge gained in the theoretical section is applied in the practical section, which contains sight-reading tips, attitude tips and play-along duets. Along the way, you will encounter hundreds of stylistically diverse duets and dozens of original compositions created for this series by an internationally diverse group of composers!

At the completion of this series, guitarists will be able to sight-read most of the notes playable on the guitar, intervals, basic chords, time signatures, key signatures, challenging rhythms, ornaments, expressions, articulations, navigation symbols, dynamics, tempi, notations for specialized guitar techniques and much more. More importantly, guitarists who have successfully completed the series will cultivate useful attitudes and behaviors for sight-reading. This method does not teach every notation applicable to guitar music. However, it does impart enough theoretical knowledge and practical skill for guitarists to successfully guide themselves toward a comprehensive understanding of guitar notation.

No prior knowledge of music theory or modern standard notation is required. In other words, when it comes to music theory and sight-reading experience, you can be a complete beginner. Of course, you will need a guitar. All types of six-string guitars in standard tuning can be used: electric, steel-string or nylon-string. You can use a pick or fingers to play the exercises and compositions.

A minimum level of intermediate playing technique is required. You are ready for this series if you can play scales and switch chords in medium-fast tempi (see the video above for a demonstration of minimum requirements). This series does not teach guitar playing technique. However, links to existing resources about relevant techniques or music theory are included for further study.

I strongly advise you to print the scores and sight-read from hard copies. The collection of exercises and compositions, entitled Keep Going Scores, is available in the Appendix. Sight-reading is easier to develop when scores are at eye level, preferably on a music stand. This placement ensures good posture, easy page turning and consistent skill acquisition. If printing is not an option then you can sight-read from soft copies, which are available in each unit.

Two types of learners can use this series.

This series is designed for a variety of learners in a variety of contexts. As a result, some content is available in several forms.

In this unit you will learn three notes, six rhythms and the most common time signature. Every unit in this series consists of two sections. The first section is theoretical. You will learn to recognize and understand the symbols used in music notation, especially as they relate to the guitar. The second section is practical. You will pluck rhythms and play duets with a recorded guitar part. Why duets? Duets inspire you to continue playing, or keep going, if you make a mistake. According to many studies, as well as my experience as a musician and educator, this method is the most efficient and fun way to become a great sight-reader. Let’s get started!

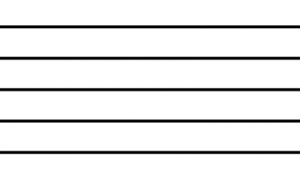

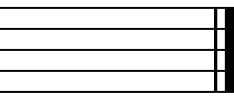

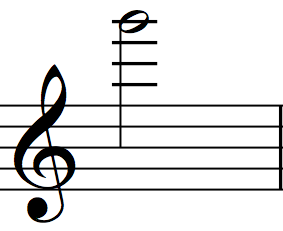

The staff consists of five equally spread out lines, which create four empty spaces. Pitch names are determined by the position of notes on the staff. Notes placed higher on the staff are higher in pitch than notes placed lower on the staff.

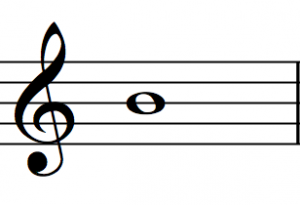

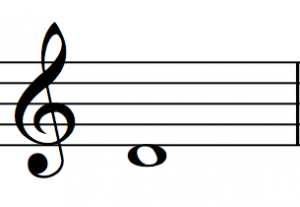

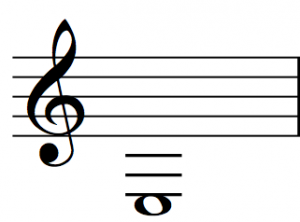

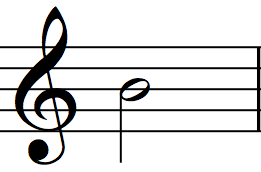

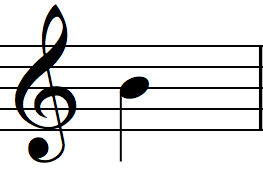

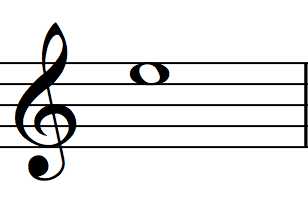

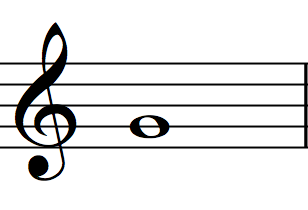

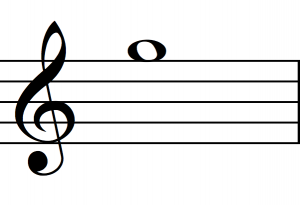

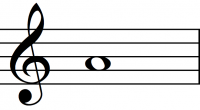

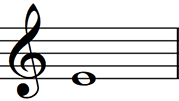

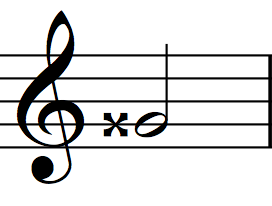

This symbol is called a G-clef. When it is placed on the staff in the manner of the example it is referred to as a treble clef. The treble clef is positioned at the beginning of each staff. Guitar music is written in treble clef, although it sounds an octave lower than written.

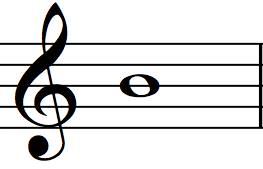

The note ‘B’ is in on the middle line of the staff. Think of in-be-tween. It is played as the second string open.

The note ‘D’ is directly below the staff. Think of ‘D’ for down because it is down below the first staff line. It is played as the fourth string open.

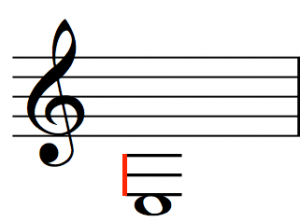

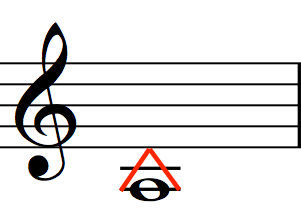

The note ‘E’ is below the third leger line. The extra lines below the staff are called leger lines. Notice that they are evenly spaced and are meant to be an extension of the staff. The note ‘E’ is played as the sixth string open. To remember the pitch ‘E’, imagine a vertical line placed to the left of the three leger lines. Notice how it makes an upper case letter ‘E’ (as shown below).

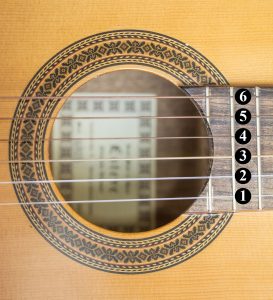

The strings on the guitar are numbered 1 through 6 from the floor upward. For example, the note ‘B’ is played as the second string open.

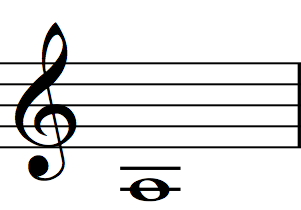

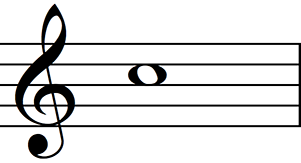

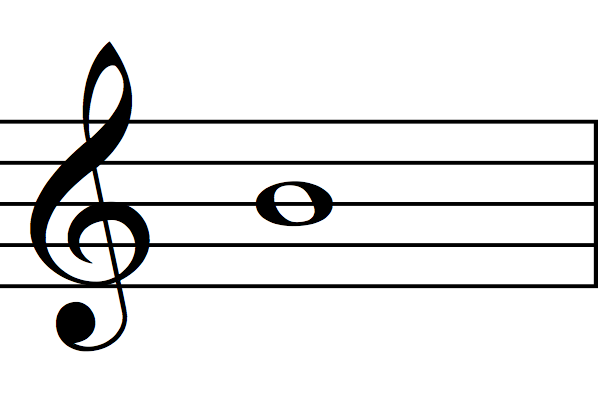

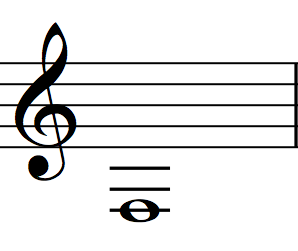

A whole note sustains for 4 beats. The whole note consists of an oval shape that is not colored in.

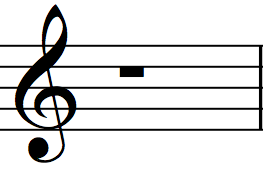

A whole rest creates silence for 4 beats. The whole note rest looks like a top hat placed upside down.

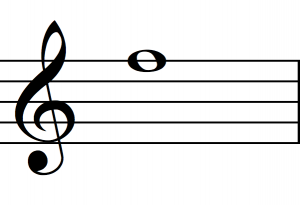

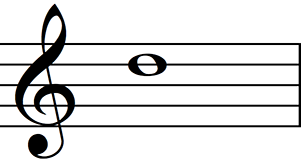

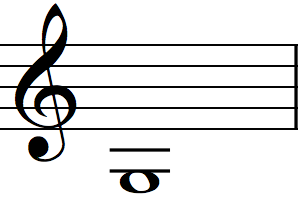

A half note sustains for 2 beats. The half note consists of an open note head and a stem.

A half rest creates silence for 2 beats. The half-note rest looks like a top hat right side up.

A quarter note sustains for 1 beat. The quarter note consists of a note head that is filled in and a stem.

A quarter rest creates silence for 1 beat. The quarter note rest is a somewhat squiggly line.

Note: I have used the note ‘B’ in the pitched examples above for the whole, half and quarter notes. However, any pitch can have any rhythm. Pitches and rhythms are the main building blocks of standard music notation and are combined in countless ways. To be an excellent sight-reader, it is important to be quick at recognizing, processing and playing pitches and rhythms.

Most songs have a steady beat. Composers typically clump the beats into groups of 2, 3 or 4, with an accent placed on the first beat of the group. The following symbols and concepts are essential to understanding rhythm in standard notation.

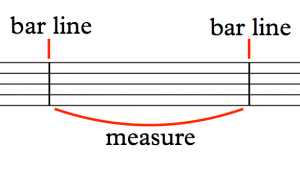

Bar lines divide the staff into measures. A measure is the space between two bar lines. Measures are important because they contain the groups of beats. If the song is grouped into four beats per measure, that means each measure must add up to four beats—no more, no less.

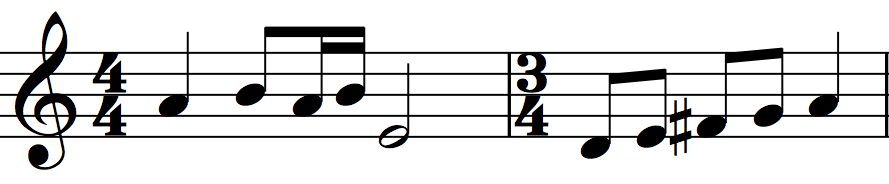

The time signature is placed at the beginning of a piece. It contains two numbers. The top number expresses how many beats are in a measure. The bottom number expresses what type of note value usually receives one beat. Think of the bottom number as a fraction with the number 1 on top. For example, in the case of the time signature to your left, 1/4 refers to a quarter note. Therefore, a 4/4 time signature = 4 x 1/4 notes per measure. Or, put another way, a 4/4 time signature contains four quarter notes per measure.

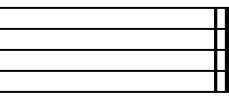

The double bar line marks the end of a musical section. Notice that both vertical lines are the same width.

The ending bar line marks the end of an entire composition. Notice that the second line vertical line is thicker than the first.

Let’s Play |

Knowledge of music notation is critical, but knowledge is not enough. Physical posture, mental attitude and good habits contribute to sight-reading successes as well. Throughout the series you will receive sight-reading tips, quotes, proverbs, poems and aphorisms to inspire keep going sight-reading.

Make sure your guitar-playing posture maintains a relatively steady guitar. When your guitar is steady you don’t have to look at your hands very often. To be a good sight-reader your eyes need to be focused on the score, not on your hands. Also, make sure your guitar-playing posture doesn’t unnecessarily strain your muscles or joints. If you have trouble with posture, I suggest you work with a teacher and/or do more careful research on the topic before launching into this series.

The most important attitude for sight-reading is what I call the keep going attitude. The keep going attitude is more concerned with keeping the pulse than perfecting pitches and rhythms. Remember, you are playing exercises. The exercises in this series are not precious. You are playing them for your personal growth, not for a performance. So, don’t worry if the music sounds messy or ugly! The only thing you must actively strive to do is to stay with the pulse.

Have fun! If you make a mistake, I suggest you laugh. Sight-reading does not have to be drudgery. Discovery, irony and even a bit of recklessness are the right attitudes for keep going sight-reading. My mentor, Theodore Norman, used to good-naturedly tease my bad sight-reading with ridiculous descriptions intended to lighten the mood, and it helped. He also advocated that guitarists respond to mistakes by nodding the head up and down, instead of left to right, to create a sense of confidence.

One way to make sight-reading more fun is to do it with another musician. I suggest you do this series with a friend. If that is not possible, treat yourself like a friend.

Count the beats 1-2-3-4- out loud, regardless of what the music demands. In other words, count throughout the entire exercise, even when you have rests. Some students experience difficulty counting out loud and playing at the same time. If you find it difficult, don’t give up! You will be able to master this skill with a bit of practice. Once you have mastered counting out loud while sight-reading, you can easily count silently, in your head.

Let’s Play Rhythms |

It’s time to put this knowledge to practice. Every unit begins with a few play-along exercises that require you to sight-read a variety of rhythms while plucking only one pitch. Click on the blue phrase with the word Score to open the musical notation in another window. Then, click on the play button under Audio to start the play-along track. Wait for the count-in to start the song. Remember, it is critical that you keep up with the beats, even if you make a mistake. Don’t forget to count out loud.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=5

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=5

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=5

Let’s Play Duets |

At the end of every unit, we will play duets. The duets encourage you to keep up with the beat. In my experience, students who stop to fix mistakes in the middle of an exercise take a long time to learn to sight-read. However, students who keep going with the beat, especially when they make mistakes, learn to sight-read quickly.

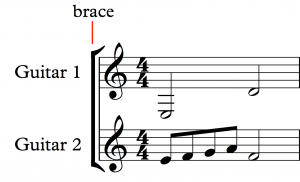

Duet notation is different from solo notation. Duet notation includes a brace that joins two staves. The word staves (rhymes with caves) refers to more than one staff. When two ore more staves are joined by brace, the unit is called a system. The system indicates that the music on both staves are to be played at the same time and according to the same pulse.

Notice the top staff is labeled Guitar 1 and the bottom staff is labeled Guitar 2. You, the student, will read from the Guitar 1 staff while I play from the Guitar 2 staff in the prerecorded, play-along tracks below. Throughout this series, you are only expected to play Guitar 1. The notation for Guitar 1 has been carefully designed to progressively build upon the concepts introduced in each unit.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=5

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=5

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=5

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=5

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=5

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

In this unit you will learn three more notes, eighth-note rhythms and two more time signatures. We will continue to follow the same procedure in which you learn symbols and then sight-read them in the Let’s Play section below. Let’s begin!

‘E’ is in the top space of the staff. It is played as the first string open.

‘G’ is on the second line of the staff. It is played as the third string open.

‘A’ is on the leger second line. It is played as the fifth string open. To remember the pitch A, imagine two diagonal lines that touch at the top and run tangentially along the note head. Notice how it makes an upper case letter A.

Rhythms

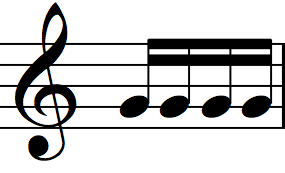

An eighth note sustains for half of a beat. The eighth note can be written in two ways: either with a beam or a flag.

When eighth notes are grouped, each note consists of a note head that is filled in, a stem and a beam. Notice that the beam connects two eighth notes.

When eighth notes are not grouped each note contains a flag(instead of a beam).

The eighth rest creates silence for half of a beat. It consists of a diagonal line with a small flag.

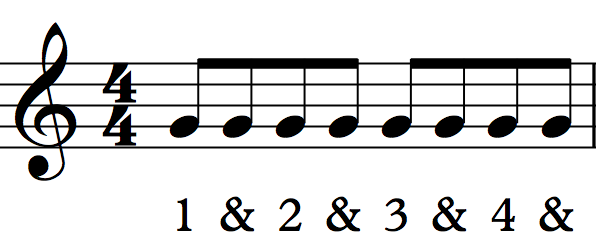

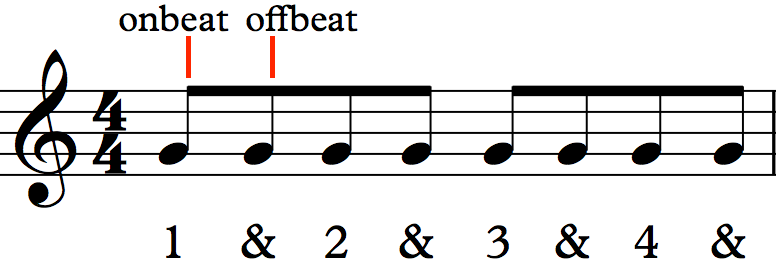

The first half of the beat receives a number that represents the beat’s placement in the measure. The second half of the beat receives the word and (represented by the symbol &). Whenever music contains eighth-note rhythms I suggest you count with ‘&’ throughout the entire piece, even when you encounter quarter, half and whole-note rhythms. This will help you maintain a steady beat.

The 2/4 time signature = 2 x 1/4 notes per measure. In other words, there are 2 quarter notes per measure. When measures contain two beat groupings, musicians refer to the music as being in duple meter. It is important to allow yourself to feel the groupings of twos and accent certain sounds accordingly.

The 3/4 time signature = 3 x 1/4 notes per measure. In other words, there are 3 quarter notes per measure. When measures contain three beat groupings, musicians refer to the music as being in triple meter. It is important to allow yourself to feel the groupings of threes and accent certain sounds accordingly. By the way, 4/4 time is considered quadruple meter because the measures contain four beat groupings.

Let’s Play |

A recent study suggests that sight-reading improves when musicians focus on the feel of the meter, instead of individual beats.Penttinen, Marjaana and Huovinen, Erkki. "The Early Development of Sight-Reading Skills in Adulthood: A Study of Eye Movements." Journal of Research in Music Education, vol. 59, no. 2, 2011, pp. 196-220. To play with the feel of the meter, start by emphasizing the first beat of each measure more than the others.

If you want to learn more about time signatures and meter please visit: http://openmusictheory.com/meter.html

For the last few decades, music educators have studied a phenomenon called chunking. Chunking is when musicians visually perceive patterns rather than individual notes. It turns out that skilled sight-readers chunk.Gromko, Joyce Eastlund. "Predictors of Music Sight-Reading Ability in High School Wind Players." Journal of Research in Music Education, vol. 52, no. 1, 2004, pp. 6-15.

You all chunk when you read words. Most of you see the letters d-o-g and immediately say dog. This is an example of chunking. But, remember what it was like when you had to sound out each individual letter: dee-oh-gee? That is pre-chunking.

The exercises under the heading Let’s Play Patterns are designed to help you process individual notes into patterns as quickly as possible. It is important to trust your instincts. I would rather you attempt to play a pattern and make mistakes than to not try at all.

Let’s Play Rhythms |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

The next exercise will have a two beat count-in because there is a 2/4 time signature at the beginning of the score. Since the smallest rhythmic value in Ex. 2.3 is an eighth note, you need to count 1&2&. From now on, please remember that the count-in always corresponds with the time signature.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

The next two exercises will have a three beat count-in because there is a 3/4 time signature at the beginning of the each score. Since the smallest rhythmic value in Ex. 2.4 is a quarter note, you simply need to count 123. However, since the smallest rhythmic value in Ex. 2.5 is an eighth note, you need to count 1&2&3&.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

Let’s Play Patterns |

The Let’s Play Patterns category will help you develop the ability to chunk. The exercises in this category are presented as guitar duets.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

Let’s Play Duets |

The exercises in this series are progressive and cumulative. They contain information you learned in this unit as well as previous units. As a result, you may need to review the symbols you learned in Unit 1.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=27

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

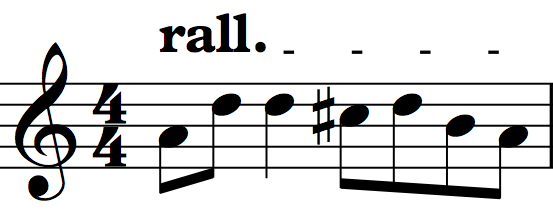

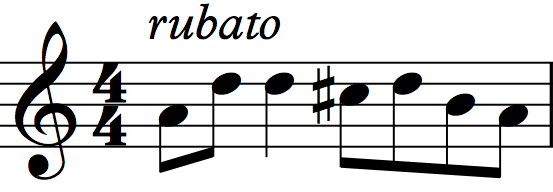

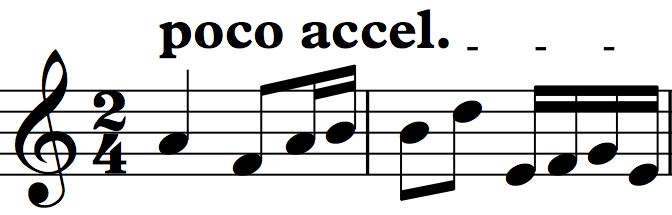

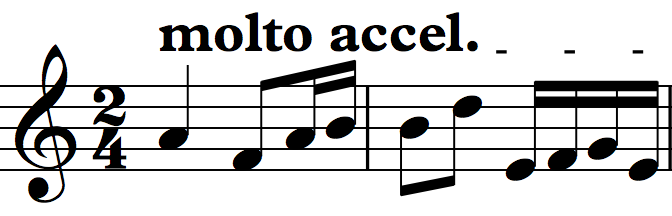

In this unit you will learn two fretted notes on the first string and a variety of tempo indicators.

‘F’ is on the top line of the staff. To play ‘F’, fret the first fret on the first string.

‘G’ sits directly on top of the staff. To play ‘G’, fret the third fret on the first string.

Tempo

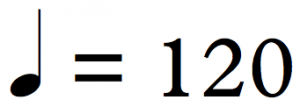

Tempo is the speed, or pace, of a piece. It can be conveyed in two ways: in beats per minute (BPM) or with descriptive words.

BPM is the most precise way to convey tempo. A rhythmic value is equated to a number that represents beats per minute. In the example, a quarter note equals 120 beats per minute, which means that the pace will unfold as two beats per second. To find an exact BPM, you can purchase a metronome or visit this free site: https://www.metronomeonline.com/.

Descriptive Words

Prior to the invention of the metronome, composers used descriptive words to indicate tempo. Many composers continue to employ these words along with or instead of metronome markings. Below is a list of ten commonly used tempo indicators. Italian words are traditionally used. You will probably encounter other words (in Italian, French, German and other languages) that are not listed here. Most of the time, the definition can be found with an online search.

| Tempo | How to Play | Approx. BPM |

| Largo | broadly | 40-60 |

| Lento | slowly | 45-60 |

| Larghetto | a little faster than Largo | 60-66 |

| Adagio | moderately slow | 66-76 |

| Andante | walking pace | 76-108 |

| Moderato | moderately | 108-120 |

| Allegro | happy, or fast | 120-168 |

| Vivace | lively and fast | 168-176 |

| Presto | very fast | 168-200 |

| Prestissimo | faster than Presto | higher than 200 |

Let’s Play |

If you drop the rhythm—meaning you lose your place while sight-reading—I suggest you play only the first beat of each measure. This will allow you to mentally keep your place in the rhythmic scheme. When that becomes manageable, play only the first and third beats of examples in 4/4 time. Finally, when that becomes manageable, play the entire exercise.

Theodore Norman advocated this method and many guitarists have used it to become great sight-readers. However, this is but one creative solution to a sight-reading obstacle. All great sight-reading guitarists engage in creative problem solving. Think of an obstacle as an opportunity to invent a creative solution. Then, create a solution and put it into action.

Let’s Play Rhythms |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

Let’s Play Patterns |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

Let’s Play Duets |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=55

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

In this unit you will learn two fretted notes on the second string and articulations.

‘C’ is in on the third space of the staff. To play ‘C’, fret the first fret on the second string.

‘D’ is on the fourth line of the staff. To play ‘D’, fret the third fret on the second string.

Articulations direct musicians to vary the emphasis of notes, and control the endings as well as the beginnings of the sounds. A phrase is a collection of notes that can be perceived as a coherent idea. Articulations alter one or more of the following aspects of a note or phrase: dynamic (loud or soft), duration (long or short) or relation to neighboring notes. Some of the most common articulations are described below.

The tenuto is a straight line. It directs you to sustain the note for the full duration of its indicated rhythmic value, or even slightly longer.

The accent is a sideways wedge. It directs you to play the note louder than its surrounding notes.

The marcato is an upward wedge. It directs you to play the note even louder than a note with an accent mark.

The staccato is a dot. It directs you to play the note shorter than its rhythmic value indicates, without speeding up.

The fermata is a semi-circle with a dot in the middle. It directs you to sustain the note(s) for longer than its indicated value, and in accordance to your musical taste. NOTE: Throughout this series, a note with a fermata symbol will be held for twice its indicated duration.

The mezzo-staccato (AKA portato or articulated legato) is a combination of a tenuto and staccato (over one note) or a slur and staccato (over more than one note). It directs you to play the phrase with a smooth yet pulsing articulation.

The breath is a comma. It directs you to pause after its preceding note, without interrupting the flow of the tempo.

The slur is a curved line that connects two or more notes. It directs you to play legato. Legato means to play the notes as a smooth and connected phrase. Sometimes the word legato will appear below the phrase.

The pull-off is a type of slur. It directs you to pluck the string to sound the first note of the group and pull the fretting finger(s) off the string to refresh string vibration for the remaining note(s) of the group. The word pull is misleading since to sound the second note, the fretting finger actually plucks the string, in a downward direction. Pull-offs are usually implied when a slur connects a higher note to a lower note. Sometimes, the letter ‘P’ is placed above the slur.

The hammer-on is another type of slur. It directs you to pluck the string for the first note of the group and hammer the fretting finger(s) onto the string to refresh string vibration for the subsequent note(s) of the group. Hammer-ons are usually implied when a slur connects a lower note to a higher note. Sometimes, the letter ‘H’ is placed above the slur.

The guitar is one of the only instruments that can consistently play multiple notes at once. As a result, one guitar can produce different conceptual elements—such as a bass line, harmony and melody—at the same time. In some genres of guitar music—such as the fugues of J.S. Bach—one guitar can produce concurrent melodies. These different musical elements are referred to as voices. Music notation strives to convey distinct voices on one score by assigning down stems to lower voices (bass) and up stems to higher voices (usually the main melody). The practice of using stem direction to show different voices is meant to help guitarists make sense of the notated musical material.

The notation above suggests two voices: a sustained bass note and a melody. Both parts are written in the same measure. The different stem directions set the voices apart. The down stem on note ‘A’ suggests it belongs to a sustained bass note. The up stem on note ‘C’ suggests it belongs to the melody. The quarter rest that precedes ‘C’ belongs to the melody too. Notice that each voice adds up to 2 beats.

Let’s Play |

Cultivate a calm demeanor. It is normal to experience uncomfortable emotions while sight-reading, especially for beginners. Nervousness, frustration, anger, panic, confusion and shame are just a few of the many feelings that arise. Allow calmness to enter into this assortment of emotions, like a ray of light piercing a stormy sky.

Let’s Play Rhythms |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=133

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=133

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=133

Let’s Play Patterns |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=133

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=133

Let’s Play Duets |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=133

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=133

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=133

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

In this unit you will learn two fretted notes on the third string and two types of dotted rhythms. You will also be introduced to the concept of syncopation.

‘A’ is in the second space of the staff. To play ‘A’, fret the second fret on the third string.

You already learned to read this note as the open second string. However, this same pitch can be played on the fourth fret of the third string as well. When you see this note in music notation you can choose whether you want to play it as the second string/open (AKA no fretting) or the third string/fourth fret.

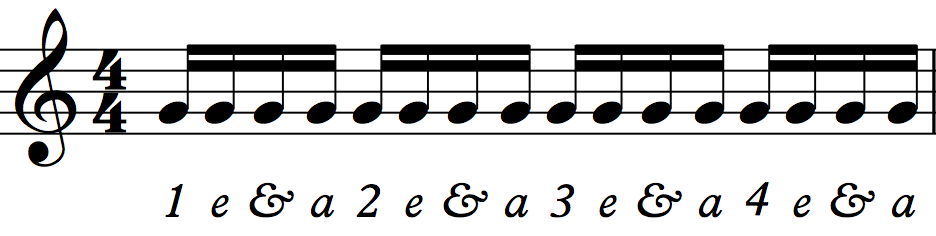

The rhythmic concepts learned in this unit often create an energizing and exciting musical effect known as syncopation. To understand syncopation you must first understand the terms onbeat and offbeat. Remember how to count eighth notes in 4/4 time?

In this example, the onbeats occur on the numbers 1,2,3,4 and the offbeats occur on the &‘s. Onbeats usually get more strength and emphasis than offbeats. The listener expects to hear emphasis on the onbeat. Syncopation plays with those expectations. When syncopation occurs, musical emphasis is either partially, or completely, placed on the offbeats rather than the onbeats. Syncopation can occur for a few beats, or for the entire piece. The following dotted rhythms often facilitate syncopation.

The dotted half note sustains for 3 beats. The dotted half note consists of a half note with a dot positioned close to the notehead.

The dotted half rest creates silence for 3 beats. The dotted half rest consist of a half note rest with a dot positioned to its right.

The dotted quarter note sustains for 1.5 beats. The dotted quarter note consists of a quarter note with a dot positioned close to the notehead.

The dotted quarter rest creates silence for 1.5 beats. The dotted quarter rest consists of a quarter note rest with a dot positioned to its right.

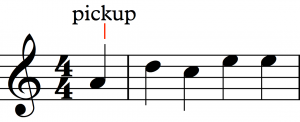

The pickup (AKA anacrusis) is a note, or small collection of notes, that precedes the first downbeat in a musical section or phrase. The downbeat is the first onbeat of each measure.

Let’s Play |

Most people experience difficulty when learning to sight-read syncopated rhythms. Find scores that contain syncopated rhythms and pluck the rhythms only. In other words, ignore the changing pitches and choose only one pitch to play so that you can focus all your attention on sight-reading rhythms. You can apply this approach to the duets in this series.

However, for a more comprehensive resource, I recommend using the book, Modern Reading Text in 4/4 for All Instruments by Louis Bellson and Gil Breines. Make sight-reading rhythms a part of your daily practice. It will increase your confidence and effectiveness in a matter of days!

Let’s Play Rhythms |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=224

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=224

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=224

Let’s Play Patterns |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=224

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=224

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=224

Let’s Play Duets |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=224

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=224

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=224

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

In this unit you will learn two notes on the fourth string, ornaments and the tie.

‘E’ is on the first space of the staff. To play ‘E’, fret the second fret on the fourth string.

‘F’ is in the first space of the staff. To play ‘F’, fret the third fret on the fourth string.

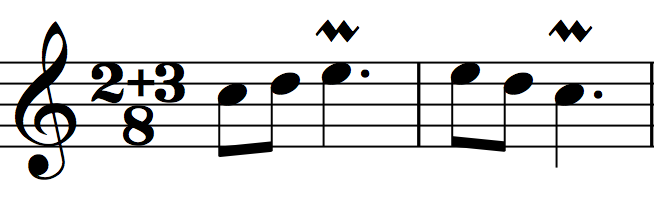

Ornaments typically embellish melody. However, ornaments can embellish harmony as well. Notice that many of the ornaments described below demand consideration of both pitch and rhythmic duration.

The acciaccatura is a note grouping in which a grace note with a line through the stem ties to a principal note. The grace note is played slightly before the downbeat of the principal note.

The bend is usually notated as upward curving line, sometimes with an arrow on the end. This symbol leaves the exact pitch of the bent note up to the performer. It can also be notated as two conjoining diagonal lines. This symbol specifies the exact pitch of the bent note. The bend directs you to either push the vibrating string toward the ceiling or pull it toward the floor. Both actions raise the pitch of the vibrating string.

The bend and release is usually notated as upward and downward curving line. It can also be notated as three conjoining diagonal lines. It directs you to pluck, bend and return the string to its starting pitch.

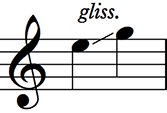

The glissando is commonly written as either a wavy or straight diagonal line connecting two notes. Sometimes the abbreviation ‘gliss.’ for glissando sits atop of the line. The glissando is a continuous slide from the starting to ending note.

The slide (AKA portamento) is commonly written as a diagonal line. Sometimes the abbreviation ‘sl.’ for slide or ‘port.’ for portamento sits atop the line. Slides can connect two specified notes with a continuous motion, in the manner of a glissando. Yet, sometimes only one note is specified and the performer can determine the other note. Typically, the performer can choose the rhythmic nuance of a slide as well.

The appoggiatura is a note grouping in which a grace note (the note in small font) ties to a principal note. The grace note is played on the downbeat of the principal note and takes approximately half its rhythmic value.

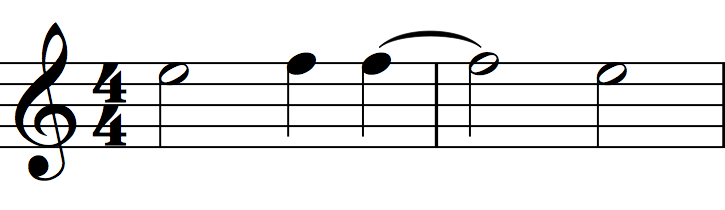

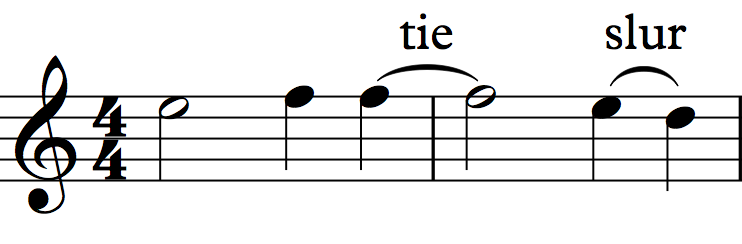

The tie is a curved line that connects notes of the same staff position and name. Tied notes sustain for the sum of their rhythmic values. Usually, the tie connects two notes across a barline. For guitarists, the tie directs us to initiate the sound by plucking only the first of the two notes and allow the second of the two notes to sustain for its stated duration. In other words, we only pluck once, not twice.

The tie may look like the slur but they function in dramatically different ways. The tie alters rhythm whereas the slur alters articulation. To tell them apart, remember the following: the tie connects two notes of the same pitch whereas the slur connects notes of different pitches.

Let’s Play |

Embrace the unexpected. Sometimes the most innovative sounds and meaningful insights arise during sight-reading. You only get one chance to have a first musical encounter with a piece. Open yourself up to the possibility of an inspiring first impression.

Let’s Play Rhythms |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=709

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=709

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=709

Let’s Play Patterns |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=709

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=709

Let’s Play Duets |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=709

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=709

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=709

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

In this unit you will learn two fretted notes on the sixth string and dynamics.

‘F’ is on the third leger line below the staff. To play ‘F’, fret the first fret on the sixth string.

‘G’ is underneath the second leger line below the staff. To play ‘G’, fret the third fret on the sixth string.

The word dynamic refers to variations in loudness. Since music notation developed over a vast period of time and place (and continues to develop) there are a few ways to notate dynamic. The dynamics in this section relate to the Italian words piano (soft), forte (strong) and mezzo (half). The list below includes the symbol, its Italian name and its musical direction. It is organized from the softest to the loudest dynamic.

| Symbol | Italian name | Musical direction |

| ppp | pianississimo | extremely soft |

| pp | pianissimo | very soft |

| p | piano | soft |

| mp | mezzopiano | moderately soft |

| mf | mezzoforte | moderately loud |

| f | forte | loud |

| ff | fortissimo | very loud |

| fff | fortississimo | extremely loud |

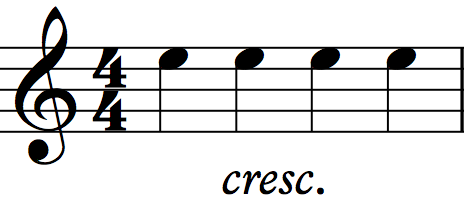

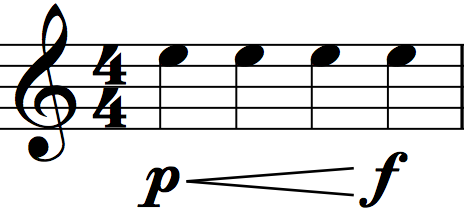

The crescendo, directs you to grow louder. The word means “increasing” in Italian.

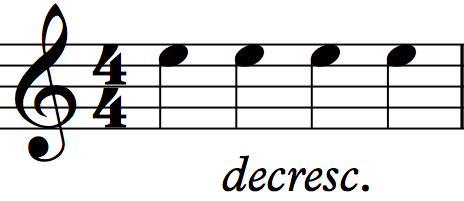

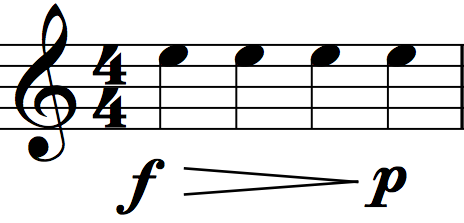

The decrescendo directs you to grow softer. The word means “decreasing” in Italian.

The diminuendo directs you to grow softer. The word means “diminishing” in Italian.

Hairpins direct you to either grow louder or softer over time. They are usually placed under the staff and relate to the notation directly above. A hairpin crescendo that widens from left to right directs you to grow louder.

A hairpin decrescendo that narrows from left to right directs you to grow softer.

The sforzando involves a sudden and loud accent. It is short for subito forzando, which means “suddenly, with force” in Italian.

The molto is a modifier that is usually paired with another dynamic (as in the example above). The word means “much” in Italian. It directs you to enact a more dramatic change of dynamic.

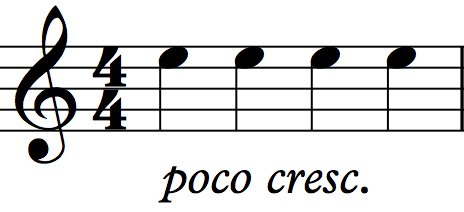

The poco is a modifier that is usually paired with another dynamic (as in the example above). The word means “little” in Italian. It directs you to enact a more subtle change of dynamic.

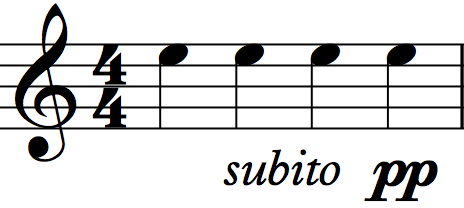

The subito is a modifier that is usually paired with another dynamic (as in the example above). The word means “suddenly” in Italian. It directs you to instantly change dynamic.

Let’s Play |

Dynamic changes force us to listen to the acoustic space, other players and our own playing. Attentive listening can create relaxation and exhilaration at the same time. Become acquainted with the diverse effects of careful listening as you sight-read.

Let’s Play Rhythms |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=928

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=928

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=928

Let’s Play Patterns |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=928

Let’s Play Duets |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=928

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=928

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

In this unit you will learn simple and compound meters. You will also begin to sight-read compositions created especially for this series!

Simple vs. Compound Meter Explained

In Unit 2 you learned to describe meter in terms of how a measure is broken down into beats. Duple meter is broken into two beats per measure; triple meter into three beats per measure; and quadruple meter into four beats per measure.

The terms introduced in this unit—simple and compound—describe how a beat is broken down into smaller subdivisions. Simply put, beats are typically subdivided (AKA broken down) into twos or threes. Meters that subdivide most of the beats into two equal parts are called simple meters; meters that subdivide most of the beats into three equal parts are called compound meters. This seemingly small distinction makes huge difference in feel. For me, music in simple meter feels angular, whereas music in compound meter feels round. Let’s explore this distinction further.

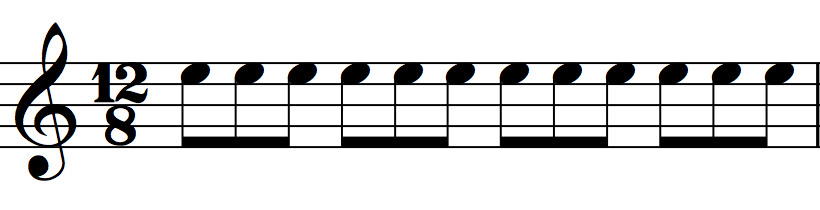

Both examples below consist of four beats per measure and are therefore in quadruple meter. However, the first one is in simple quadruple meter and the second is in compound quadruple meter.

In simple meter most beats are broken into two equal parts. Notice how the eighth notes are beamed in groups of two to emphasize the subdivision of the beat.

Therefore, in simple meter, each beat is represented by a quarter note.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

In compound meter most beats are broken into three equal parts. Notice how the eighth notes are beamed in groups of three to emphasize the subdivision of the beat.

Therefore, in compound meter, each beat is represented by a dotted-quarter note.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

Six Types of Standard Meter

Similarly, duple and triple meters can be expressed in simple and compound as well. Thus, there are six types of standard meter in Western music:

In simple duple meter most beats divide into eighth notes. There are two beats per measure and each beat is a quarter note.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

In simple triple meter most beats divide into eighth notes. There are three beats per measure and each beat is a quarter note.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

In simple quadruple meter most beats divide into eighth notes. There are four beats per measure and each beat is a quarter note.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

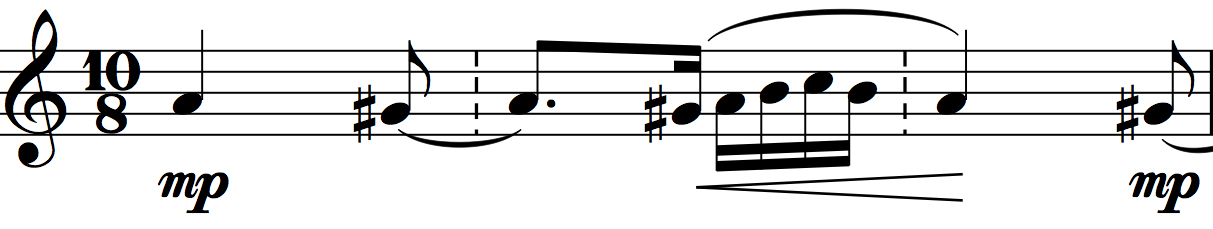

In compound duple meter most beats divide into three eighth notes. There are two beats per measure and each beat is equivalent to a dotted-quarter note. This meter can be counted in a variety of ways. The graphic above presents two options. I recommend using the second option because it emphasizes the duple feel.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

In compound triple meter most beats divide into three eighth notes. There are three beats per measure and each beat is equivalent to a dotted-quarter note. This meter can be counted in a variety of ways. The graphic above presents two options. I recommend using the second option because it emphasizes the triple feel.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

In compound quadruple meter most beats divide into three eighth notes. There are four beats per measure and each beat is equivalent to a dotted-quarter note. This meter can be counted in a variety of ways. The graphic above presents two options. I recommend using the second option because it emphasizes the quadruple feel.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

The Hemiola

The hemiola is a device in which rhythmic accents switch from two beats subdivided in three parts to three beats subdivided in two parts (or vice versa). It creates excitement and energy. I suggest you emphasize the change in accent whenever you encounter a hemiola.

When a hemiola appears in compound meter the rhythmic accents switch from two beats subdivided in three parts to three beats subdivided in two parts.

When a hemiola appears in simple meter the rhythmic accents switch from three beats subdivided in two parts to two beats subdivided in three parts.

To determine meter, you can employ the following short cut. Look to the top number of the time signature.

| Simple duple | 2 |

| Simple triple | 3 |

| Simple quadruple | 4 |

| Compound duple | 6 |

| Compound triple | 9 |

| Compound quadruple | 12 |

Simple Meter

As you learned in Unit 2, the bottom number of the time signature, in simple meter, corresponds to the type of note that becomes a single beat (AKA pulse, in this case). Therefore, if the bottom number is ‘4,’ then each beat is represented by a quarter note. It’s pretty simple, which is why it is called simple meter.

Compound Meter

In compound meter, the bottom number of the time signature corresponds to the type of note that becomes a one-third division of the beat (AKA pulse, in this case). If compound meter is notated such that the dotted-quarter note is the beat (as in the examples above) then the eighth note is the one-third division of the dotted-quarter. Hence, the number ‘8’ takes the place of the bottom number of the time signature.

Let’s Play |

Sight-reading empowers you to engage with music you may have never heard before. Many musicians derive oodles of joy from bringing music notation to life for the first hearing. It is like unwrapping a present! Further, sight-reading creates an opportunity to decide whether a piece is worth investing the time needed to make it performance-ready.

When I started sight-reading for the purpose of scouting new performance repertoire, I finally stopped confusing the act of sight-reading with the act of performing. When I sight-read, my goal is to get a sense of the shape, character and difficulties of a piece. Sometimes, mistakes do not get in the way of achieving that goal, which is why they can be ignored. However, when I prepare for performance, my goal is to master the shape, character and difficulties of a piece. In this case, mistakes are crucial to goal attainment. Mistakes are obstacles that, when overcome, clear the path to greater mastery.

I want you to experience the difference between a sight-reading attitude and a performance-preparation attitude. This was one of my motivations for commissioning composers to write over thirty original duet compositions for this series. You do not have to perfect these compositions. All you have to do is sight-read them. If you don’t like the piece, feel free to continue through the series without mastering it. However, if you do like one or more of the compositions, I encourage you to shift from a sight-reading attitude to a performance-preparation attitude so you can add them to your performance repertoire. The original compositions are available in the Appendix as a collection entitled The Obelisks.

Let’s Play Rhythms |

Throughout this unit the count-in click for pieces in compound meter will include the eighth note subdivision of each beat. An emphasis will be placed on the beginning of each beat to help establish the compound meter feel .

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

Let’s Play Patterns |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

Let’s Play Duets |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

The compositions composed for this series are complied into a collection called The Obelisks. The collection is available for viewing and downloading in the Appendix (forthcoming). I hope you are inspired to perform these pieces and learn about the composers who contributed to this series.

Let’s Play Compositions |

These compositions are under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=961

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

In this unit you will learn more notes on the first string, accidentals and the eighth-note triplet.

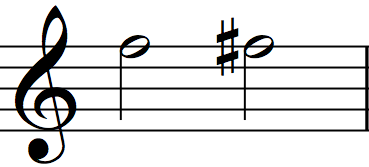

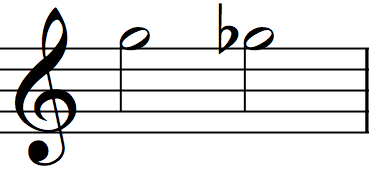

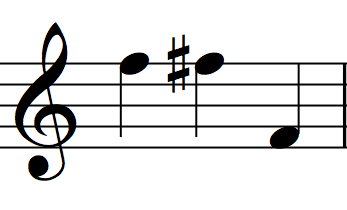

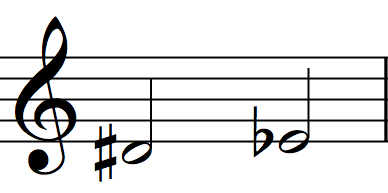

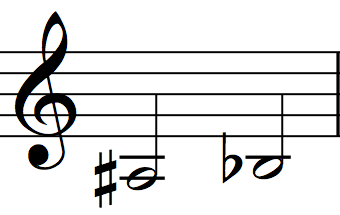

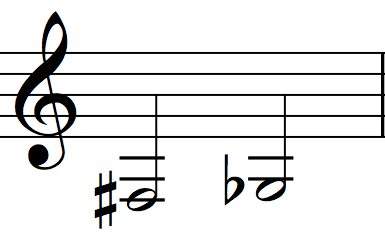

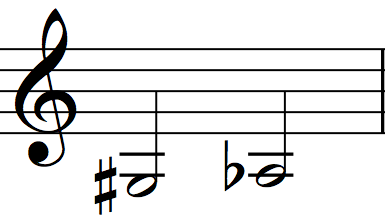

Accidentals are symbols that pair with a notes to create new notes. Three common accidentals are: the sharp (♯), the flat (♭) and the natural (♮).

| Name | Symbol | Effect |

| Sharp | ♯ | The sharp raises pitch up one fret. |

| Flat | ♭ | The flat lowers pitch down one fret. |

| Natural | ♮ | The natural cancels the effect of a sharp or flat. |

In this example, ‘F’ is played as the first fret/first string. ‘F♯’ is played as the second fret/first string. Since they produce different pitches, they are considered different notes.

In this example, ‘G’ is played as the third fret/first string. ‘G♭’ is played as the second fret/first string.

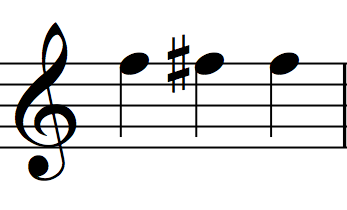

In this example, ‘F’ is played as the first fret/ first string; ‘F♯’ is played as the second fret/first string; ‘F♮’ is played as the first fret/first string again. The natural symbol cancelled the sharp of the previous note.

Notice how the placement of the accidental in speech and writing is different from the placement of the accidental in music notation. For example, the sharp symbol follows the note when we say or write ‘F♯,’ whereas the sharp symbol precedes the note in music notation.

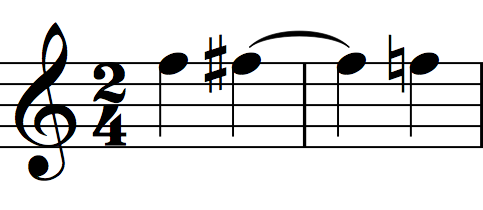

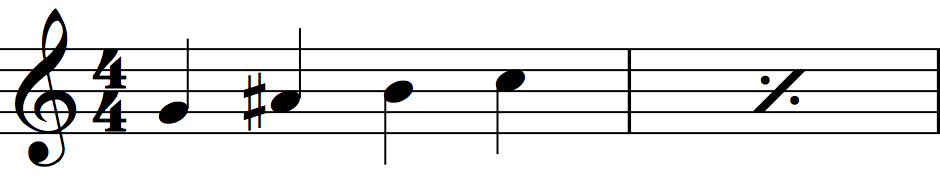

Accidentals apply to successive notes on the same staff position for the remainder of the measure in which they occur, unless explicitly changed by another accidental. The effect of the accidental ends once a barline is passed (there is one exception to this rule, which will be discussed below, under the heading The Tie & Accidentals).

In the example above, the ‘F’ on beat one is played as the first fret, the ‘F♯’ on beat two is played as the second fret and the ‘F♯’ on beat three is played as the second fret as well. The note on beat three is indeed an ‘F♯’ even though the sharp was not added to it in the score.

In the example above, the ‘F’ on beat one is played as the first fret/first string, the ‘F♯’ on beat two is played as the second fret/first string and the ‘F’ on beat three is played as the third fret/fourth string. The note on beat three is an ‘F’ (not and ‘F♯’) because the ‘F’ on beat two is a different staff position than the ‘F’ on beat three.

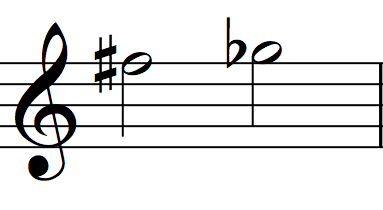

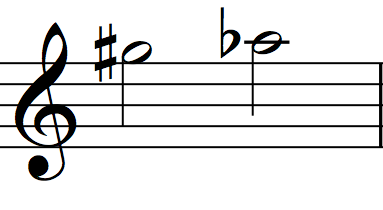

Did you notice in the first two examples that ‘F♯’ and ‘G♭’ are both played as the second fret/first string? ‘F♯’ and ‘G♭’ create the same pitch. For that reason, we call them enharmonic equivalents. Enharmonics (for short) are notes that create the same pitch, despite being notated differently. If you are curious to know more about enharmonics, you may enjoy taking a music theory course.

F♯ and G♭are enharmonics. To play ‘F♯’ and ‘G♭’, fret the second fret on the first string.

‘G♯’ and ‘A♭’ are enharmonics. To play ‘G♯’ and ‘A♭’, fret the fourth fret on the first string.

‘A’ is on the first leger line above the staff. To play ‘A’, fret the fifth fret on the first string.

When a note that has been altered by an accidental ties to the same note across a barline, the accidental is carried through. However, subsequent notes at the same staff position in the second bar are not affected by the accidental that was carried through with the tied note.

In this example, the tied note on beat one/measure two is an F♯. However, the note on beat two/measure two is an F natural. Some scores will include the natural as a helpful reminder. This is called a courtesy accidental. Bear in mind that some scores do not include courtesy accidentals. In this case, you are expected to know the rule and play the correct pitch.

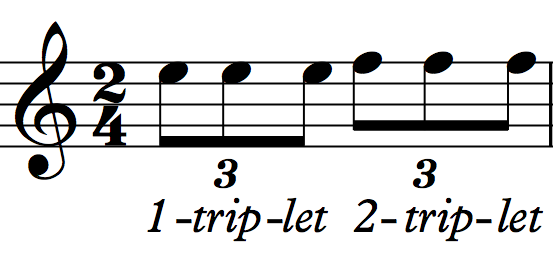

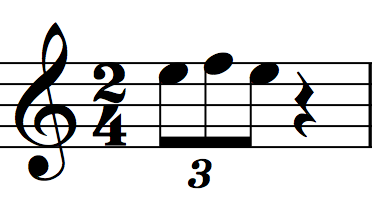

In Unit 2 you learned to subdivide the quarter note into two equal parts using eighth notes. The example above contains an eighth-note triplet, which subdivides a quarter note into three equal parts. Notice that three eighth notes are beamed together along with a hovering number ‘3’. The number ‘3’ is what alters the math of the eighth note. In a triplet, each eighth note represents one-third of a beat.

The eighth-note triplet can include a two-third/one-third grouping as well. In the example above, the quarter note sustains for two-thirds of a beat and the eighth note sustains for one-third of a beat.

Let’s Play |

It is important to develop the feel of the triplet subdivision through focused practice. I recommend counting triplets along with a metronome click. Set the metronome to quarter note = 80 BPM and count ‘ta-ki-te’ in the space of every click. Alternatively, you can count ‘1-trip-let, 2-trip-let.’ Make sure the subdivisions are equally spaced and that you say ‘ta‘ or the beat number at the same time as the click. Triplets have a unique feel. You will begin to intuitively transition from the triplet feel to the non-triplet feel and back after dedicated and focused practice.

Let’s Play Rhythms |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1023

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1023

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1023

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1023

Let’s Play Patterns |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1023

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1023

Let’s Play Duets |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1023

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1023

Let’s Play Compositions |

This composition is under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1023

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

In this unit you will learn more fretted notes on the third string, symbols for small-scale repetition and fingerings.

‘G♯’ and ‘A♭’ are enharmonics. To play ‘G♯’ or ‘A♭’, fret the first fret on the third string.

‘A♯’ and ‘B♭’ are enharmonics. To play ‘A♯’ or ‘B♭’, fret the third fret on the third string.

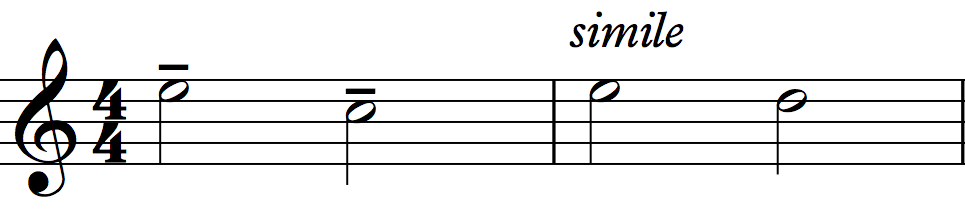

The simile means “in a similar way.” Sometimes it is seen in notation as the abbreviation sim. It directs you to continue playing in the manner previously marked. In the example below, the simile refers to the tenuto articulations.

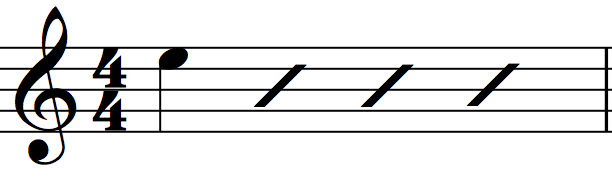

The one-beat repeat is a diagonal line placed in the middle of the staff. It directs you to repeat the music from the preceding beat. It is important to mention that this symbol is often employed in jazz and popular music and suggests that you strum according to style or personal taste.

The one-measure repeat consists of a diagonal line with a dot on either side that is placed in the middle of an empty measure. It directs you to repeat the music from the preceding measure.

The two-measure repeat consists of two diagonal lines with dots on either side that is placed on the barline between two empty measures. It directs you to play the music from the two preceding measures.

The four-measure repeat consists of four diagonal lines with dots on either side that is placed on the barline between four empty measures. It directs you to play the music from the four preceding measures.

Fingerings specify which fingers to use and where to place them. The plucking-hand and fretting-hand each have a unique set of symbols.

The plucking-hand fingering convention is universal. Each italicized letter corresponds with a Spanish word for a specific finger (with the exception of the pinky finger). See the example below.

| Symbol | Spanish | English |

| p | pulgar | thumb |

| i | indicio | index |

| m | medio | middle |

| a | annular | ring |

| e or x | pinky |

The fretting-hand fingering convention is more complicated because it can involve up to three extra symbols per note. Fingerings can easily clutter the score with too much visual information, which is why I recommend playing from scores in which composers or editors apply fingering notations sparingly. Two fretting-hand fingering conventions are explained in this unit: the standard method and Norman method (named for its inventor, Theodore Norman). Both methods use Arabic numerals to represent fretting-fingers.

| Symbol | Finger |

| 1 | index |

| 2 | middle |

| 3 | ring |

| 4 | pinky |

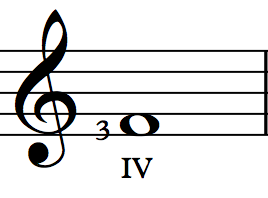

In the standard method, Arabic numbers (without circles) represent fretting fingers; circled Arabic numbers represent string numbers; and Roman numerals represent fret numbers. See the example of the standard method below.

| Symbol | Direction | |

| Arabic number 3 | Fretting finger | |

| Circled Arabic number 3 | String number | |

| Roman numeral IV | Fret number |

In the Norman method, Arabic numbers (without circles) represent fretting fingers and Roman numerals represent string numbers. Fret numbers are typically not employed in the Norman method because there is only one place per string where a note of the same staff position can be played. Therefore, if you are given the string number you can determine the suggested fret number on your own. See the example of the Norman method below.

| Symbol | Direction | |

| Arabic number 3 | Fretting finger | |

| Roman numeral IV | String number |

I believe the Norman method is more effective than the standard method at reducing the amount of visual information on the score. It also fosters an intuitive approach to sight-reading. However, because the standard method is more common, it will be applied to most compositions and exercises throughout the series.

Let’s Play |

If the score you intend to sight-read contains a lot of fingerings, do not feel inclined to follow them at first. More often than not, an editor (not a composer) adds fingerings to a score as helpful suggestions. In this case, the editor’s fingerings are not mandatory. However, sometimes a composer will assign fingerings in order to achieve a particular timbre or phrasing. In this case, fingerings provide deeper insight into a composer’s musical intentions. In either case, fingerings do not need to factor into a first or second sight-reading encounter. Remember, too much visual information on the page can slow down mental processing.

Let’s Play Rhythms |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

Let’s Play Patterns |

Remember, Roman numerals represent string numbers.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

In the next exercise, the simile in measure 3 directs you to continue accenting in the manner of measures 1 and 2.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

Let’s Play Duets |

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

Let’s Play Compositions |

These compositions are under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

The piece below provides two sight-reading opportunities. I suggest you sight-read the Guitar 1 melody first and the vocal melody second.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1066

You have completed this unit! If you kept up with the beat and accurately played approximately 70% of the pitches and rhythms, you are ready for the next unit. Feel free to repeat the exercises. However, do not play them so often that you memorize them. Once you memorize the notation, you are no longer developing the skill of sight-reading.

In this unit you will learn more fretted notes on the fourth string, sixteenth rhythms and dotted eighth rhythms. You will also learn how to apply these rhythms in both simple and compound meters.

‘D♯’ and ‘E♭’ are enharmonics. To play ‘D♯’ or ‘E♭’, fret the first fret on the fourth string.

‘F♯’ and ‘G♭’ are enharmonics. To play ‘F♯’ or ‘G♭’, fret the fourth fret on the fourth string.

You already learned to read this note as the open third string. However, this same pitch can be played as the fifth fret of the fourth string as well.

In simple meter, a sixteenth note sustains for one-quarter of a beat. The sixteenth note can be written in two ways: either with two beams or two flags.

Four sixteenth notes are written here. The sixteenth note consists of a note head that is colored in, a stem and two beams. In this example, the beam connects four sixteenth notes. Four sixteenth notes add up to one quarter note.

In this example, the sixteenth notes contain flags instead of beams.

A sixteenth rest creates silence for one-quarter of a beat. The sixteenth rest consists of a diagonal line with two small flags.

The first sixteenth receives a number, which represents the beat’s placement in the measure. The second sixteenth receives the sound ‘ee.’ The third sixteenth receives the word ‘&.’ The fourth sixteenth receives the sound ‘ah.’ When you play music with sixteenth rhythms, I suggest you count with “1e&a…” throughout the entire piece, even when you encounter eighth, quarter, half and whole note rhythms. This will help you maintain a steady beat. View the video above for examples of counting throughout this unit.

The dotted eighth note sustains for three-quarters of a beat. The dotted eighth note consists of an eighth note with a dot positioned close to the notehead.

The dotted eighth rest creates silence for three-quarters of a beat. The dotted eighth rest consists of an eighth rest with a dot positioned close to the symbol.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1068

Since the dotted eighth holds for three-quarters of a beat and the sixteenth holds for one-quarter of a beat, they frequently beam together to form a group that adds up to one beat. The example above shows two combinations that frequently appear in music.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1068

Eighth notes and sixteenth notes also frequently beam together to adds up to one beat. The example above shows three possible combinations.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1068

In Unit 9 you learned the following about compound meter: the dotted quarter note sustains for a beat and the eighth note sustains for one-third of a beat. Therefore, the sixteenth note sustains for one-sixth of a beat. The graphic above shows two possible ways of counting sixteenths in compound meter.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1068

Eighth notes and sixteenth notes frequently beam together to form groups that add up to one beat. The example above shows three of the many possible combinations.

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: https://press.rebus.community/sightreadingforguitar/?p=1068