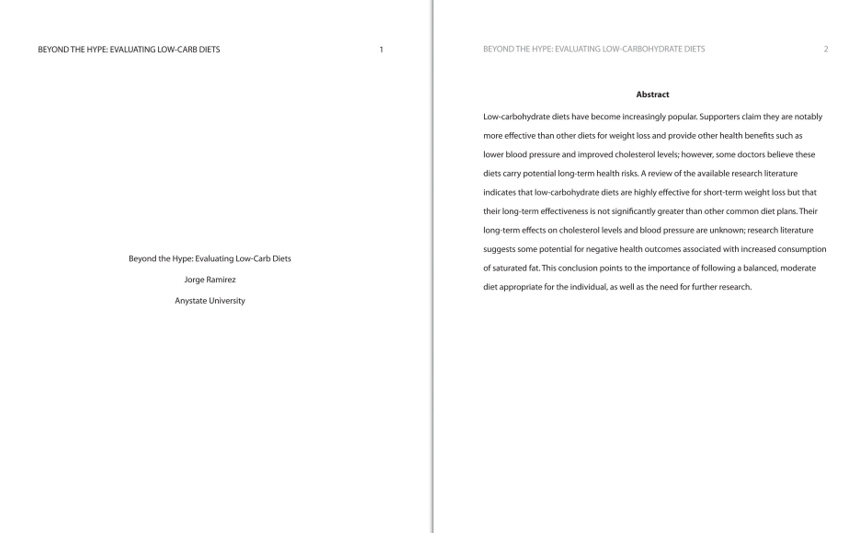

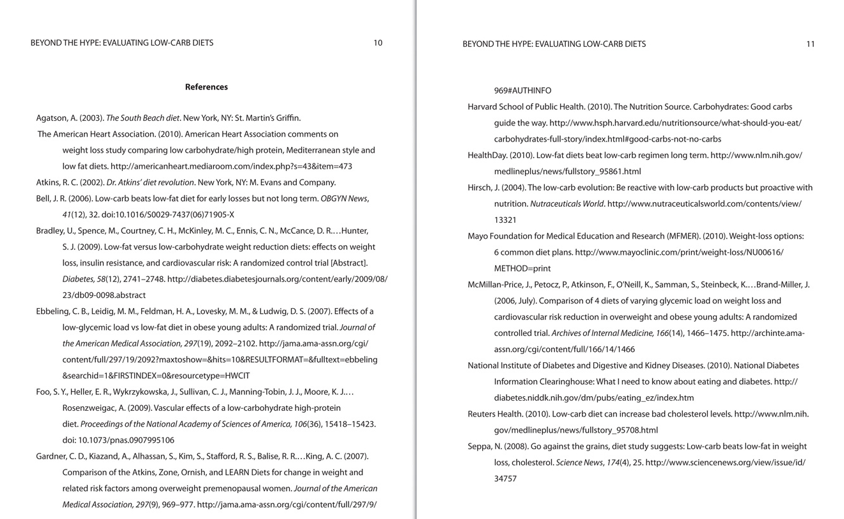

This section provides detailed information about how to create the references section of your paper. You will review basic formatting guidelines and learn how to format bibliographical entries for various types of sources.

Formatting the References Section: The Basics

At this stage in the writing process, you may already have begun setting up your references section. This section may consist of a single page for a brief research paper or may extend for many pages in professional journal articles. As you create this section of your paper, follow the guidelines provided here.

Formatting the References Section

To set up your references section, use the insert page break feature of your word-processing program to begin a new page. Note that the header and margins will be the same as in the body of your paper, and pagination continues from the body of your paper. (In other words, if you set up the body of your paper correctly, the correct header and page number should appear automatically in your references section.) See additional guidelines below.

Formatting Reference Entries

Reference entries should include the following information:

- The name of the author(s)

- The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

- The full title of the source

- For books, the city of publication

- For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

- For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

- For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

See the following examples for how to format a book or journal article with a single author.

- Use author’s last name and initials followed by periods.

- Use a single space between parts of the entry. Include periods and other punctuation as indicated.

- Use sentence case for book titles.

- Use standard postal abbreviations for the state where the source was published

- Use a colon between the city of publication, and the publisher.

Atkins, R.C. (2002). Dr. Atkin’s diet revolution. New York, NY: M. Evans and Company.

- Use sentence case for article titles. Do not use quotation marks around the title.

- Use title case for journal titles and italicize the title.

- Include the volume number in italics followed by the issue number in parentheses, with no space between them.

- Include commas after the journal title and issue number.

- Include the page number(s) where the article appears. Use an en dash between page numbers.

Bass, D. N. (2010). Frad in the lunchroom? Education Next, 10(1), 67-71.

The following box provides general guidelines for formatting the reference page. For the remainder of this chapter, you will learn about how to format bibliographical entries for different source types, including multiauthor and electronic sources.

- Include the heading References, centered at the top of the page. The heading should not be boldfaced, italicized, or underlined.

- Use double-spaced type throughout the references section, as in the body of your paper.

- Use hanging indentation for each entry. The first line should be flush with the left margin, while any lines that follow should be indented five spaces. Note that hanging indentation is the opposite of normal indenting rules for paragraphs.

- List entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. For a work with multiple authors, use the last name of the first author listed.

- List authors’ names using this format: Smith, J. C.

- For a work with no individual author(s), use the name of the organization that published the work or, if this is unavailable, the title of the work in place of the author’s name.

- For works with multiple authors, follow these guidelines:

- For works with up to seven authors, list the last name and initials for each author.

- For works with more than seven authors, list the first six names, followed by ellipses, and then the name of the last author listed.

- Use an ampersand before the name of the last author listed.

- Use title case for journal titles. Capitalize all important words in the title.

- Use sentence case for all other titles—books, articles, web pages, and other source titles. Capitalize the first word of the title. Do not capitalize any other words in the title except for the following:

- Proper nouns

- First word of a subtitle

- First word after a colon or dash

- Use italics for book and journal titles. Do not use italics, underlining, or quotation marks for titles of shorter works, such as articles.

Set up the first page of your references section and begin adding entries, following the APA formatting guidelines provided in this section.

- If there are any simple entries that you can format completely using the general guidelines, do so at this time.

- For entries you are unsure of how to format, type in as much information as you can, and highlight the entries so you can return to them later.

Formatting Reference Entries for Different Source Types

As is the case for in-text citations, formatting reference entries becomes more complicated when you are citing a source with multiple authors, citing various types of online media, or citing sources for which you must provide additional information beyond the basics listed in the general guidelines. The following guidelines show how to format reference entries for these different situations.

Print Sources: Books

For book-length sources and shorter works that appear in a book, follow the guidelines that best describes your source.

A book by two or more authors

List the authors’ names in the order they appear on the book’s title page. Use an ampersand before the last author’s name.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

An edited book with no author

List the editor or editors’ names in place of the author’s name, followed by Ed. or Eds. in parentheses.

Myers, C., & Reamer, D. (Eds.). (2009). 2009 nutrition index. San Francisco, CA: HealthSource, Inc.

An edited book with an author

List the author’s name first, followed by the title and the editor or editors. Note that when the editor is listed after the title, you list the initials before the last name.

Dickinson, E. (1959). Selected poems & letters of Emily Dickinson. R. N. Linscott.(Ed.). Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

*Capitalize “Ed.” when the abbreviation refers to an editor.

TIP: The previous example shows the format used for an edited book with one author—for instance, a collection of a famous person’s letters that has been edited. This type of source is different from an anthology, which is a collection of articles or essays by different authors. For citing works in anthologies, see the guidelines later in this section.

A translated book

Include the translator’s name after the title, and at the end of the citation, list the date the original work was published. Note that for the translator’s name, you list the initials before the last name.

Freud, S. (1965). New introductory lectures on psycho-analysis (J. Strachey, Trans.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton. (Original work published 1933).

A book published in multiple editions

If you are using any edition other than the first edition, include the edition number in parentheses after the title.

A chapter in an edited book

List the name of the author(s) who wrote the chapter, followed by the chapter title. Then list the names of the book editor(s) and the title of the book, followed by the page numbers for the chapter and the usual information about the book’s publisher.

Hughes, J.R., & Pierattini, R. A. (1992). An introduction to pharmacotherapy for mental disorders. In J. Grabowski & G. VandenBos (Eds.), Psychopharmacology (pp. 97 -125). Washington, DC: American Psychology Association.

*Include the abbreviation “pp.” when listing the pages where a chapter or article appear in a book.

A work that appears in an anthology

Follow the same process you would use to cite a book chapter, substituting the article or essay title for the chapter title.

Beck, A. T., & Young, J. (1986). College blues. In D. Goleman & D. Heller (Eds.), The pleasures of psychology (pp. 309-323). New York, NY: New American Library.

*Include the abbreviation “pp.” when listing the pages where a chapter or article appears in a book.

An article in a reference book

List the author’s name if available; if no author is listed, provide the title of the entry where the author’s name would normally be listed. If the book lists the name of the editor(s), include it in your citation. Indicate the volume number (if applicable) and page numbers in parentheses after the article title.

The census. (2006). In J.W. Wright (Ed.), The New York Times 2006 almanac (pp. 268-275). New York, NY: Penguin.

*Capitalize proper nouns that appear in a book title.

Two or more books by the same author

List the entries in order of their publication year, beginning with the work published first.

Swedan, N. (2001). Women’s sports medicine and rehabilitation. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers.Swedan, N. (2003). The active woman’s health and fitness handbook. New York, NY: Perigee.

If two books have multiple authors, and the first author is the same but the others are different, alphabetize by the second author’s last name (or the third or fourth, if necessary).

Carroll, D., & Aaronson, F. (2008). Managing type II diabetes. Chicago, IL: Southwick Press. Carroll, D., & Zuckerman, N. (2008). Gestational diabetes. Chicago, IL: Southwick Press.

Books by different authors with the same last name

Alphabetize entries by the authors’ first initial.

Smith, I. K. (2008). The 4-day diet. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Smith, S. (2008). The complete guide to Navy Seal fitness: Updated for today’s warrior elite (3rd ed.). Long Island City, NY: Hatherleigh Press.

*Capitalize the first word of a subtitle.

A book authored by an organization

Treat the organization name as you would an author’s name. For the purposes of alphabetizing, ignore words like The in the organization’s name. (That is, a book published by the American Heart Association would be listed with other entries whose authors’ names begin with A.)

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV (4th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

A book-length report

Format technical and research reports as you would format other book-length sources. If the organization that issued the report assigned it a number, include the number in parentheses after the title. (See also the guidelines provided for citing works produced by government agencies.)

Jameson, R., & Dewey, J. (2009). Preliminary findings from an evaluation of the president’s physical fitness program in Pleasantville school district. Pleasantville, WA: Pleasantville Board of Education.

A book authored by a government agency

Treat these as you would a book published by a nongovernment organization, but be aware that these works may have an identification number listed. If so, include it in parentheses after the publication year.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2002). The decennial censuses from 1790 to 2000 (Publication No. POL/02-MA). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Offices.

Revisit the references section you began to compile in Exercise 27.1. Use the guidelines provided to format any entries for book-length print sources that you were unable to finish earlier.

Review how Jorge formatted these book-length print sources:

- Atkins, R. C. (2002). Dr. Atkins’ diet revolution. New York, NY: M. Evans and Company.

- Agatson, A. (2003). The South Beach diet. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Print Sources: Periodicals

An article in a scholarly journal

Include the following information:

- Author or authors’ names

- Publication year

- Article title (in sentence case, without quotation marks or italics)

- Journal title (in title case and in italics)

- Volume number (in italics)

- Issue number (in parentheses)

- Page number(s) where the article appears

DeMarco, R. F. (2010). Palliative care and African American women living with HIV. Journal of Nursing Education, 49(5), 1–4.

An article in a journal paginated by volume

In these types of journals, page numbers for one volume continue across all the issues in that volume. For instance, the winter issue may begin with page 1, and in the spring issue that follows, the page numbers pick up where the previous issue left off. (If you have ever wondered why a print journal did not begin on page 1, or wondered why the page numbers of a journal extend into four digits, this is why.) Omit the issue number from your reference entry.

Wagner, J. (2009). Rethinking school lunches: A review of recent literature. American School Nurses’ Journal, 47, 1123–1127.

An abstract of a scholarly article

At times you may need to cite an abstract—the summary that appears at the beginning—of a published article. If you are citing the abstract only, and it was published separately from the article, provide the following information:

- Publication information for the article

- Information about where the abstract was published (for instance, another journal or a collection of abstracts)

Romano, S. (2005). Parental involvement in raising standardized test scores. [Abstract]. Elementary Education Abstracts, 19, 36.

*Use this format for abstracts published in a collection of abstracts.

Simpson, M. J. (2008) Assessing educational progress: Beyond standardized testing. Journal of the Association for School Administrative Professionals, 35(4), 32-40. Abstract obtained from Assessment in Education, 2009, 73(6), Abstract No. 537892.

*Use this format for abstracts published in another journal.

A journal article with two to seven authors

List all the authors’ names in the order they appear in the article. Use an ampersand before the last name listed.

Barker, E. T., & Bornstein, M. H. (2010). Global self-esteem, appearance satisfaction, and self-reported dieting in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(2), 205–224.

Tremblay, M. S., Shields, M., Laviolette, M., Craig, C. L., Janssen, I., & Gorber, S. C. (2010). Fitness of Canadian children and youth: Results from the 2007–2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Reports, 21(1), 7–20.

A journal article with more than seven authors

List the first six authors’ names, followed by a comma, an ellipsis, and the name of the last author listed. The article in the following example has sixteen listed authors; the reference entry lists the first six authors and the sixteenth, omitting the seventh through the fifteenth.

Straznicky, N.E., Lambert, E.A., Nestel, P. J., McGrane, M. T., Dawood, T., Schlaich, M. P., … Lambert, G. W. (2010). Sympathetic neural adaptation to hypocaloric diet with or without exercise training in obese metabolic syndrome subjects. Diabetes, 59(1), 71-79.

*Because some names are omitted, use a comma and ellipsis, rather than an ampersand, before the final name listed.

Writing at work

The idea of an eight-page article with sixteen authors may seem strange to you—especially if you are in the midst of writing a ten-page research paper on your own. More often than not, articles in scholarly journals list multiple authors. Sometimes, the authors actually did collaborate on writing and editing the published article. In other instances, some of the authors listed may have contributed to the research in some way while being only minimally involved in the process of writing the article. Whenever you collaborate with colleagues to produce a written product, follow your profession’s conventions for giving everyone proper credit for their contribution.

A magazine article

After the publication year, list the issue date. Otherwise, treat these as you would journal articles. List the volume and issue number if both are available.

A newspaper article

Treat these as you would magazine and journal articles, with one important difference: precede the page number(s) with the abbreviation p. (for a single-page article) or pp. (for a multipage article). For articles whose pagination is not continuous, list all the pages included in the article. For example, an article that begins on page A1 and continues on pages A4 would have the page reference A1, A4. An article that begins on page A1 and continues on pages A4 and A5 would have the page reference A1, A4–A5.

Corwin, C. (2009, January 24). School board votes to remove soda machines from county schools. Rockwood Gazette, pp. A1-A2.

*Include ths section in your page reference.

A letter to the editor

After the title, indicate in brackets that the work is a letter to the editor.

Jones, J. (2009, January 31). Food police in our schools [Letter to the editor]. Rockwood Gazette, p. A8.

A review

After the title, indicate in brackets that the work is a review and state the name of the work being reviewed. (Note that even if the title of the review is the same as the title of the book being reviewed, as in the following example, you should treat it as an article title. Do not italicize it.)

Penhollow, T.M., & Jackson, M.A. (2009). Drug abuse: Concept, prevention, and cessation [Review of the book Drug abuse: Concepts, prevention, and cessation]. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33(5), 620-622.

*Italicize the title of the reviewed book only where it appears in brackets.

Revisit the references section you began to compile in Exercise 27.1. Use the guidelines provided above to format any entries for periodicals and other shorter print sources that you were unable to finish earlier.

Electronic Sources

Citing articles from online periodicals: URLs and Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs)

Whenever you cite online sources, it is important to provide the most up-to-date information available to help readers locate the source. In some cases, this means providing an article’s URL, or web address. (The letters URL stand for uniform resource locator.) Always provide the most complete URL possible. Provide a link to the specific article used, rather than a link to the publication’s homepage.

As you know, web addresses are not always stable. If a website is updated or reorganized, the article you accessed in April may move to a different location in May. The URL you provided may become a dead link. For this reason, many online periodicals, especially scholarly publications, now rely on DOIs rather than URLs to keep track of articles.

A DOI is a Digital Object Identifier—an identification code provided for some online documents, typically articles in scholarly journals. Like a URL, its purpose is to help readers locate an article. However, a DOI is more stable than a URL, so it makes sense to include it in your reference entry when possible. Follow these guidelines:

- If you are citing an online article with a DOI, list the DOI at the end of the reference entry.

- If the article appears in print as well as online, you do not need to provide the URL. However, include the words Electronic version after the title in brackets.

- In other respects, treat the article as you would a print article. Include the volume number and issue number if available. (Note, however, that these may not be available for some online periodicals).

An article from an online periodical with a DOI

List the DOI if one is provided. There is no need to include the URL if you have listed the DOI.

Bell, J. R. (2006). Low-carb beats low-fat diet for early losses but not long term. OBGYN News, 41(12), 32. doi:10.1016/S0029-7437(06)71905-X

An article from an online periodical with no DOI

List the URL. Include the volume and issue number for the periodical if this information is available. (For some online periodicals, it may not be.)

Laufer-Cahana, A. (2010, March 15). Lactose intolerance do’s and don’ts. Salon. Retrieved from http://www.salon.con/food/feature/2010/03/15/lactose_intolerance_ayala

*Used the words “Retrieved from” before the URL

**This publication is online-only, so a URL must be included in the citation.

***Do not include a period after the URL.

Note that if the article appears in a print version of the publication, you do not need to list the URL, but do indicate that you accessed the electronic version.

Robbins, K. (2010, March/April). Nature’s bounty: A heady feast [Electronic version]. Psychology Today, 43(2), 58.

A newspaper article

Provide the URL of the article.

McNeil, D. G. (2010, May 3). Maternal health: A new study challenges benefits of vitamin A for women and babies. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/04/health/04glob.html?ref=health

An article accessed through a database

Cite these articles as you would normally cite a print article. Provide database information only if the article is difficult to locate.

TIP: APA style does not require writers to provide the item number or accession number for articles retrieved from databases. You may choose to do so if the article is difficult to locate or the database is an obscure one. Check with your professor to see if this is something they would like you to include.

An abstract of an article

Format these as you would an article citation, but add the word Abstract in brackets after the title.

Bradley, U., Spence, M., Courtney, C. H., McKinley, M. C., Ennis, C. N., McCance, D. R.…Hunter, S. J. (2009). Low-fat versus low-carbohydrate weight reduction diets: Effects on weight loss, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular risk: A randomized control trial [Abstract]. Diabetes, 58(12), 2741–2748. http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/early/2009/08/23/db00098.abstract

A nonperiodical web document

The ways you cite different nonperiodical web documents may vary slightly from source to source, depending on the information that is available. In your citation, include as much of the following information as you can:

- Name of the author(s), whether an individual or organization

- Date of publication (Use n.d. if no date is available.)

- Title of the document

- Address where you retrieved the document

If the document consists of more than one web page within the site, link to the homepage or the entry page for the document.

American Heart Association. (2010). Heart attack, stroke, and cardiac arrest warning signs. Retrieved from http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3053

An entry from an online encyclopedia or dictionary

Because these sources often do not include authors’ names, you may list the title of the entry at the beginning of the citation. Provide the URL for the specific entry.

Addiction. (n.d.) In Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/addiction

Data sets

If you cite raw data compiled by an organization, such as statistical data, provide the URL where you retrieved the information. Provide the name of the organization that sponsors the site.

US Food and Drug Administration. (2009). Nationwide evaluation of X-ray trends: NEXT surveys performed [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Radiation-EmittingProducts/RadiationSafety/NationwideEvaluationofX- RayTrendsNEXT/ucm116508.htm

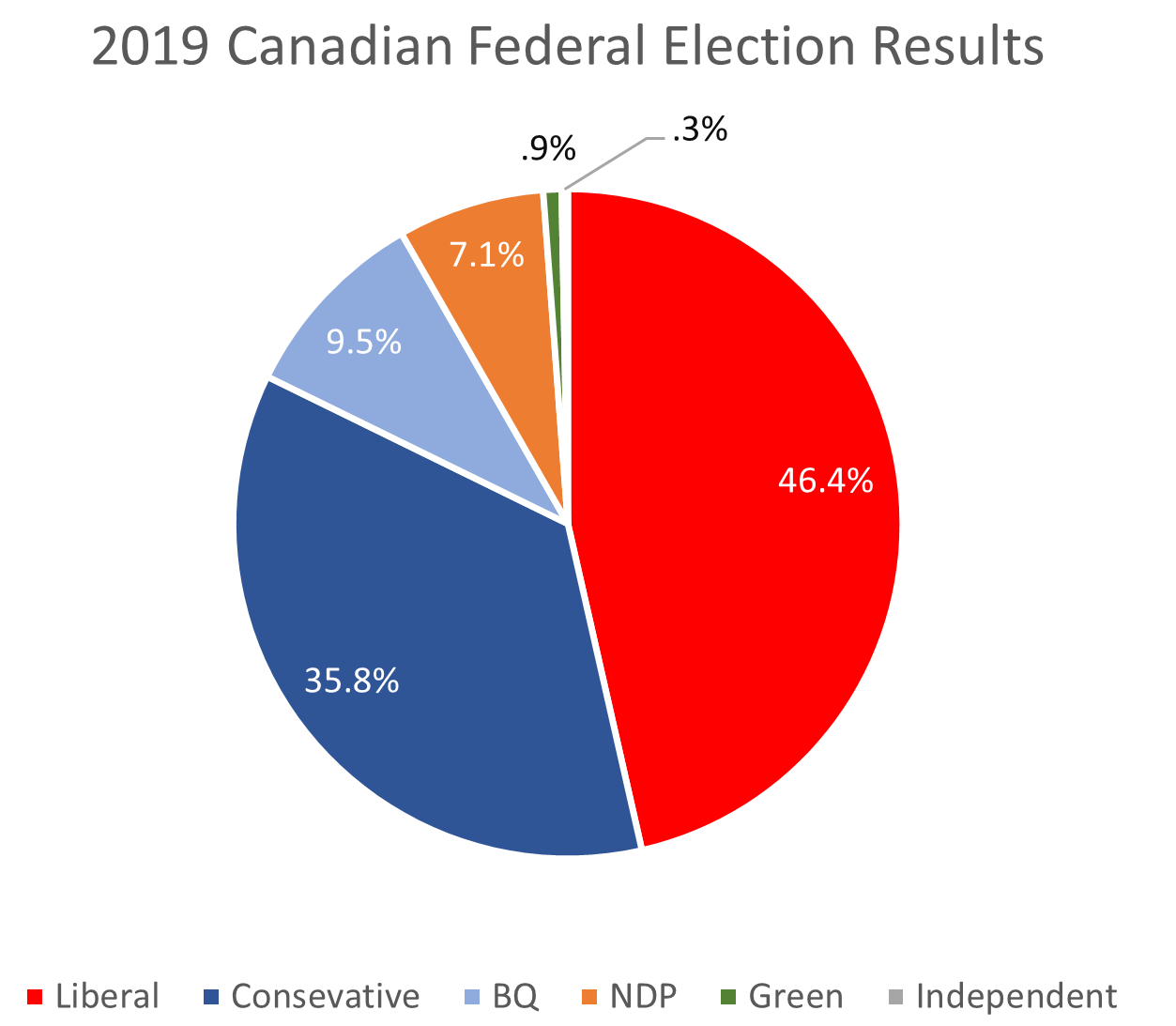

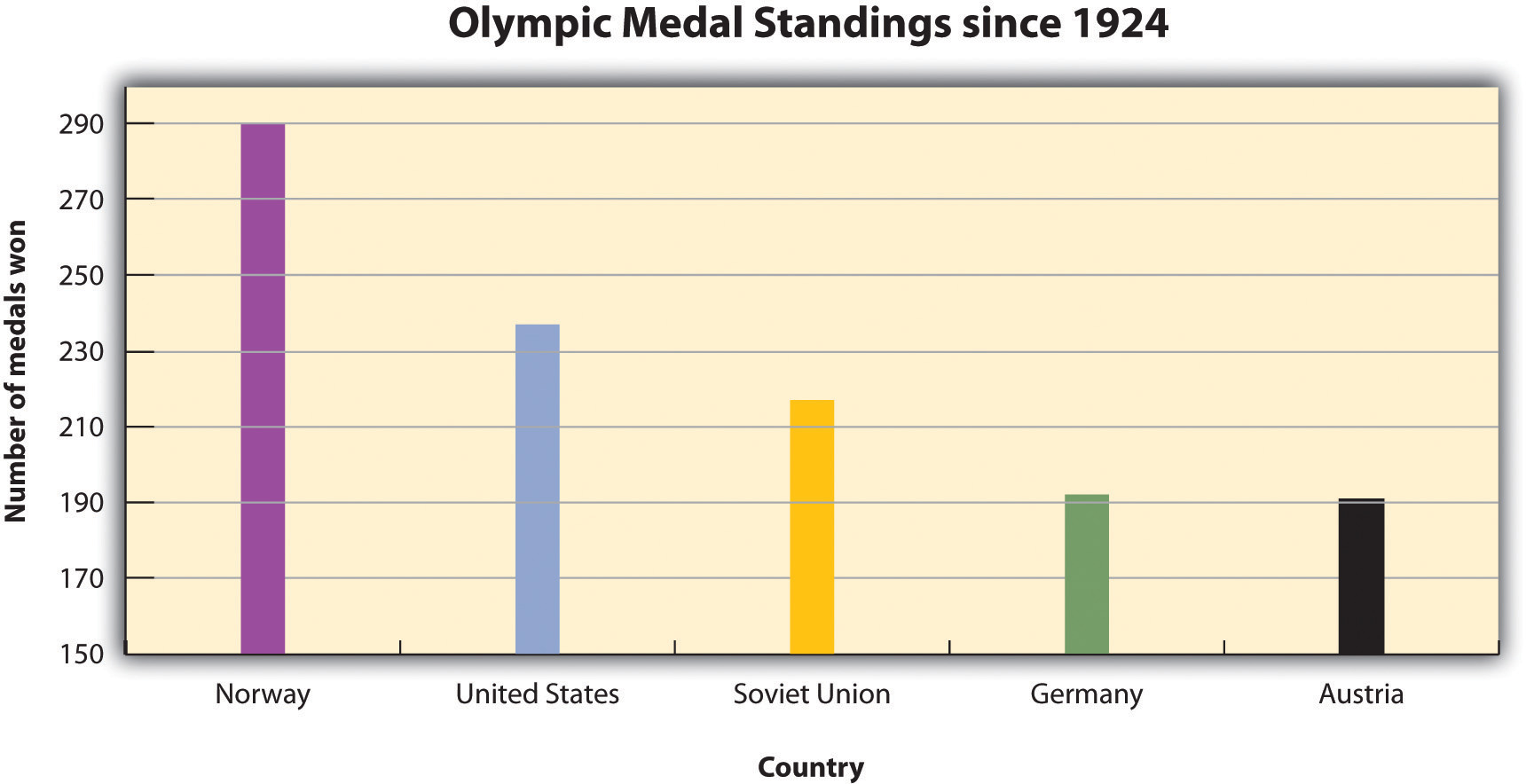

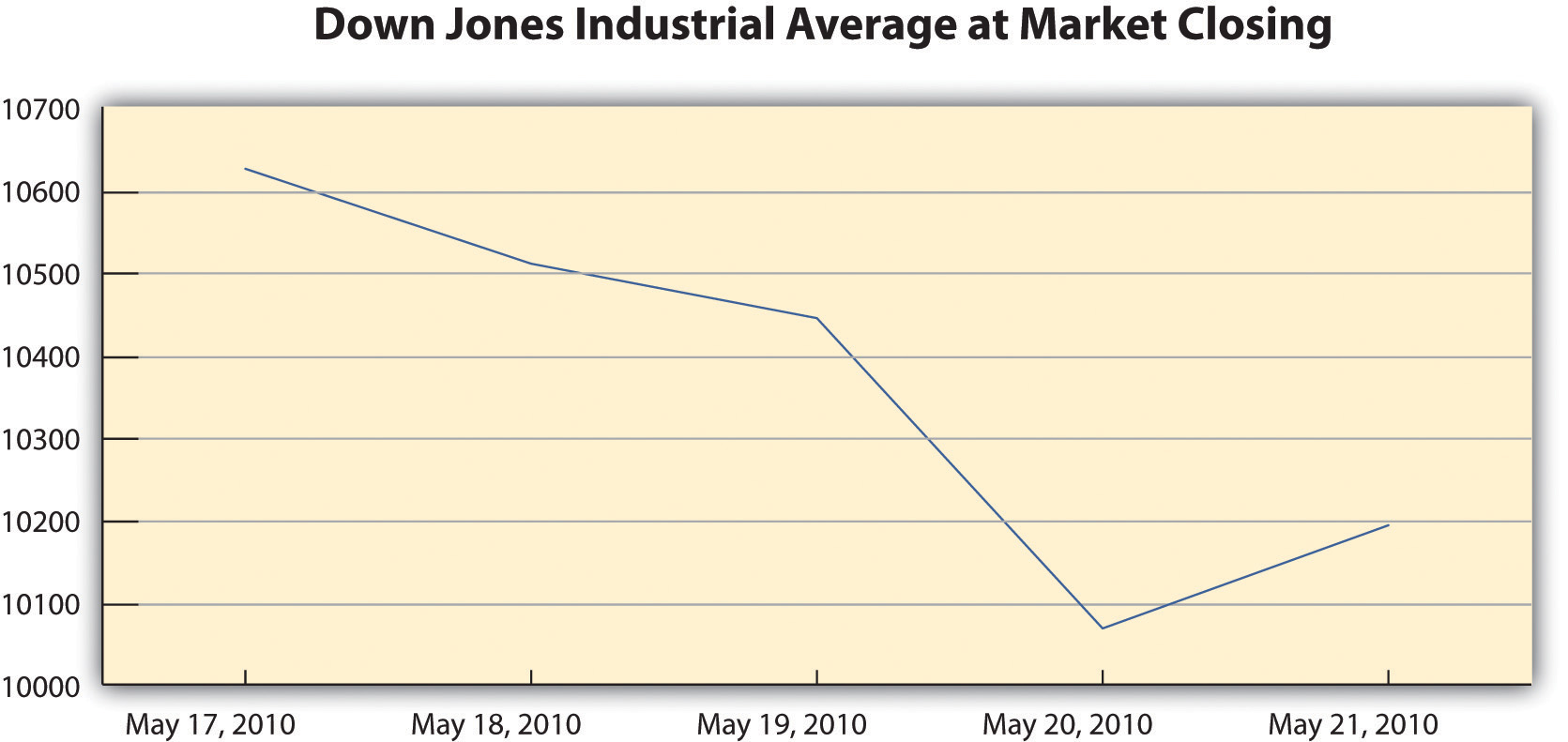

Graphic data

When citing graphic data—such as maps, pie charts, bar graphs, and so on—include the name of the organization that compiled the information, along with the publication date. Briefly describe the contents in brackets. Provide the URL where you retrieved the information. (If the graphic is associated with a specific project or document, list it after your bracketed description of the contents.)

US Food and Drug Administration. (2009). [Pie charts showing the percentage breakdown of the FDA’s budget for fiscal year 2005]. 2005 FDA budget summary. Retrieved from mhttp://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/ReportsManualsForms/Reports/BudgetReports/2005FDABudgetSummary/ucm117231.htm

An online interview (audio file or transcript)

List the interviewer, interviewee, and date. After the title, include bracketed text describing the interview as an “Interview transcript” or “Interview audio file,” depending on the format of the interview you accessed. List the name of the website and the URL where you retrieved the information. Use the following format.

Davies, D. (Interviewer), & Pollan, M. (Interviewee). (2008). Michael Pollan offers president food for thought [Interview transcript]. Retrieved from National Public Radio website: http://www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=100755362

An electronic book

Electronic books may include books available as text files online or audiobooks. If an electronic book is easily available in print, cite it as you would a print source. If it is unavailable in print (or extremely difficult to find), use the format in the example. (Use the words Available from in your citation if the book must be purchased or is not available directly.)

Chisholm, L. (n.d.). Celtic tales. Retrieved from http://www.childrenslibrary.org/icdl/BookReader?bookid= chicelt_00150014&twoPage=false&route=text&size=0&fullscreen=false&pnum1=1&lang= English&ilang=English

A chapter from an online book or a chapter or section of a web document

These are treated similarly to their print counterparts with the addition of retrieval information. Include the chapter or section number in parentheses after the book title.

Hart, A. M. (1895). Restoratives—Coffee, cocoa, chocolate. In Diet in sickness and in health (VI). Retrieved from http://www.archive.org/details/dietinsicknessin00hartrich

A dissertation or thesis from a database

Provide the author, date of publication, title, and retrieval information. If the work is numbered within the database, include the number in parentheses at the end of the citation.

Coleman, M.D. (2004). Effect of a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet on bone mineral density, biomarkers of bone turnover, and calcium metabolism in healthy premenopausal females. Retrieved from Virginia Tech Digital Library & Archives: Electronic Theses and Dissertations. (etd-07282004-174858)

*Italicize the titles of theses and dissertations.

Computer software

For commonly used office software and programming languages, it is not necessary to provide a citation. Cite software only when you are using a specialized program, such as the nutrition tracking software in the following example. If you download software from a website, provide the version and the year if available.

Internet Brands, Inc. (2009). FitDay PC (Version 2) [Software]. Available from http://www.fitday.com/Pc/PcHome.html?gcid=14

A post on a blog or video blog

Citation guidelines for these sources are similar to those used for discussion forum postings. Briefly describe the type of source in brackets after the title.

Fazio, M. (2010, April 5). Exercising in my eighth month of pregnancy [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://somanyblogs.com/~faziom/postID=67

*Do not italicize the titles of blog or video blog postings.

A television or radio broadcast

Include the name of the producer or executive producer; the date, title, and type of broadcast; and the associated company and location.

West, Ty. (Executive producer). (2009, September 24). PBS special report: Health care reform [Television broadcast]. New York, NY, and Washington, DC: Public Broadcasting Service.

A television or radio series or episode

Include the producer and the type of series if you are citing an entire television or radio series.

Couture, D., Nabors, S., Pinkard, S., Robertson, N., & Smith, J. (Producers). (1979). The Diane Rehm show [Radio series]. Washington, DC: National Public Radio.

To cite a specific episode of a radio or television series, list the name of the writer or writers (if available), the date the episode aired, its title, and the type of series, along with general information about the series.

Bernanke, J., & Wade, C. (2010, January 10). Hummingbirds: Magic in the air [Television series episode]. In F. Kaufman (Executive producer), Nature. New York, NY: WNET.

A motion picture

Name the director or producer (or both), year of release, title, country of origin, and studio.

Spurlock, M. (Director/producer), Morley, J. (Executive producer), & Winters. H. M. (Executive producer). (2004). Super size me. United States: Kathbur Pictures in association with Studio on Hudson.

A recording

Name the primary contributors and list their role. Include the recording medium in brackets after the title. Then list the location and the label.

Smith, L. W. (Speaker). (1999). Meditation and relaxation [CD]. New York, NY: Earth, Wind, & Sky Productions.

Székely, I. (Pianist), Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Performers), & Németh, G. (Conductor). (1988). Chopin piano concertos no. 1 and 2 [CD]. Hong Kong: Naxos.

A podcast

Provide as much information as possible about the writer, director, and producer; the date the podcast aired; its title; any organization or series with which it is associated; and where you retrieved the podcast.

Kelsey, A. R. (Writer), Garcia, J. (Director), & Kim, S. C. (Producer). (2010, May 7). Lies food labels tell us. Savvy consumer podcasts [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from http://www.savvyconsumer.org/podcasts/050710

Revisit the references section you began to compile in Exercise 27.1.

- Use the APA guidelines provided in this section to format any entries for electronic sources that you were unable to finish earlier.

- If your sources include a form of media not covered in the APA guidelines here, consult with a writing tutor or review a print or online reference book. You may wish to visit the website of the American Psychological Association or the Purdue University Online Writing lab, which regularly updates its online style guidelines.

- Give your paper a final edit to check the references section.

your citations for these kinds of sources according to APA guidelines.

Text Attributions

- This chapter was adapted from “Creating a References Section” in Writing for Success by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution (and republished by University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing). Adapted by Allison Kilgannon. CC BY-NC-SA.