Note: Many of these definitions are taken or based upon the writing of the original authors. See the Source Chapter Attributions page for more information.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A

Ability Model: an approach that views EI as a standard intelligence that utilizes a distinct set of mental abilities that (1) are intercorrelated, (2) relate to other extant intelligences, and (3) develop with age and experience.

Abnormal Psychology: The application of psychological science to understanding and treating mental disorders.

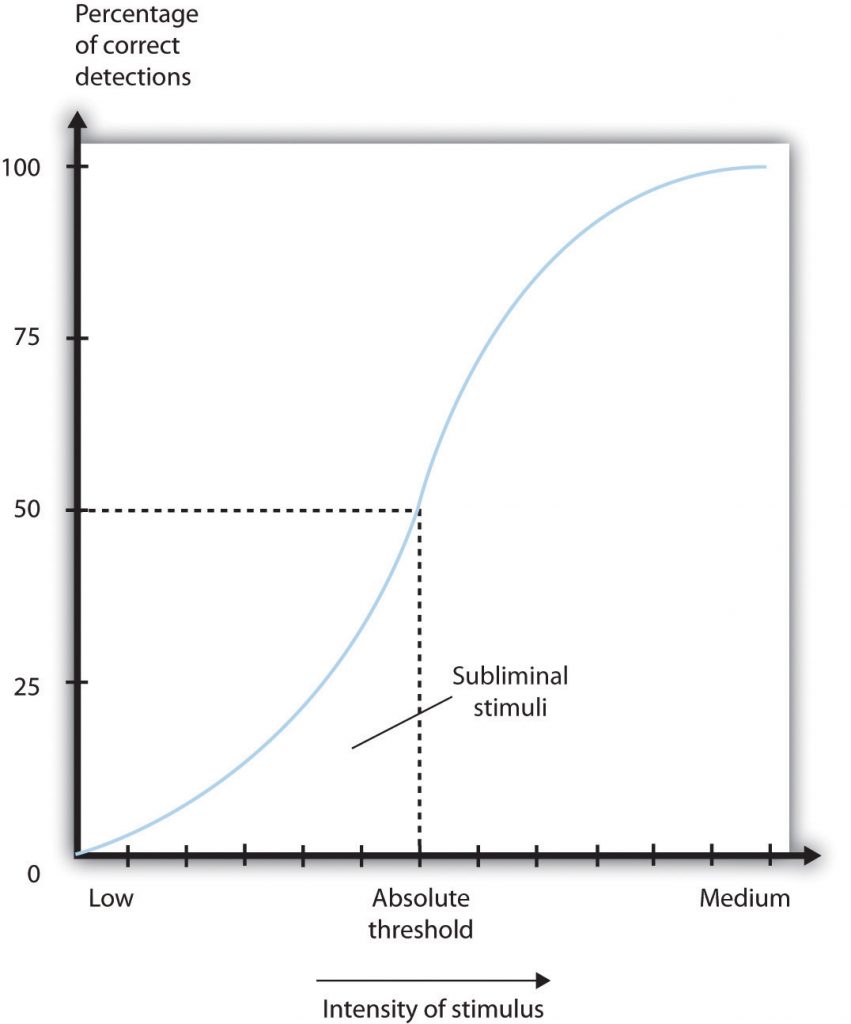

Absolute Threshold of a Sensation: the intensity of a stimulus that allows an organism to just barely detect it.

Access: Conscious experience that recalls experiences from memory.

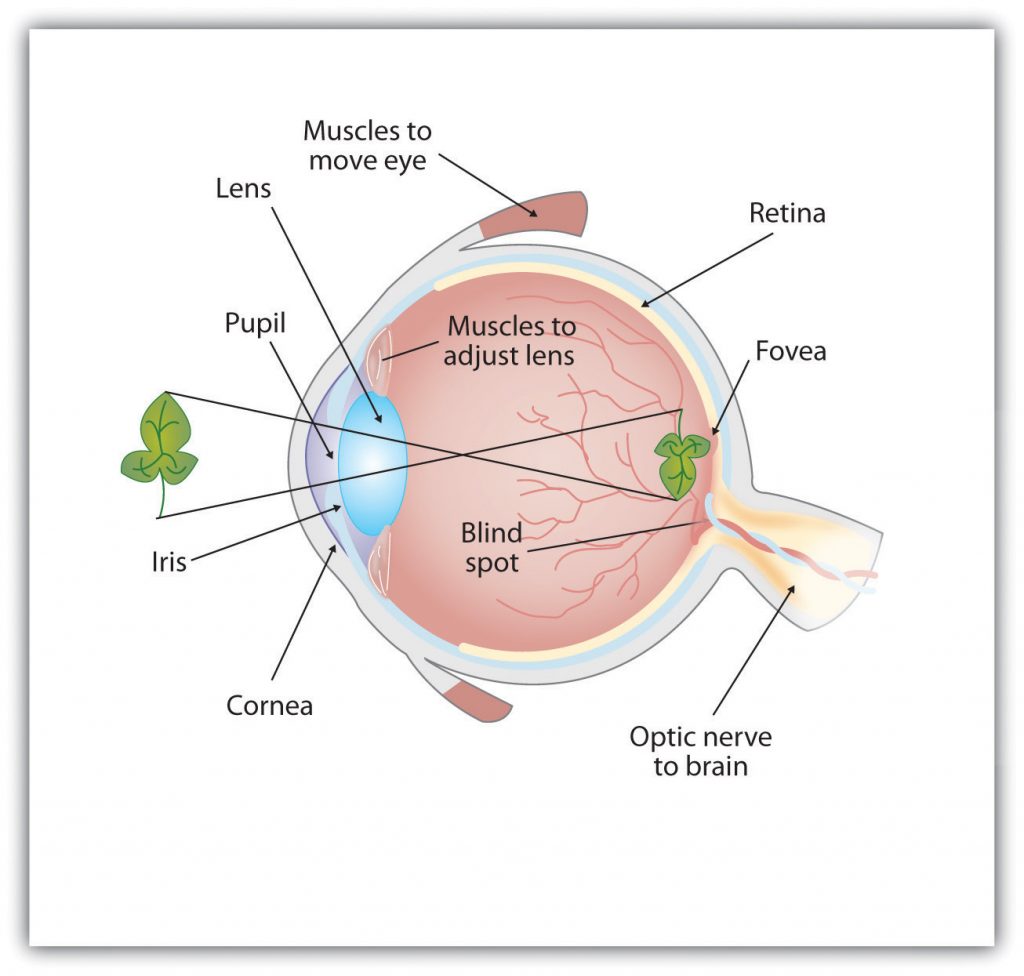

Accommodation: helps determine visual depth. As the lens changes its curvature to focus on distant or close objects, information relayed from the muscles attached to the lens helps us determine an object’s distance.

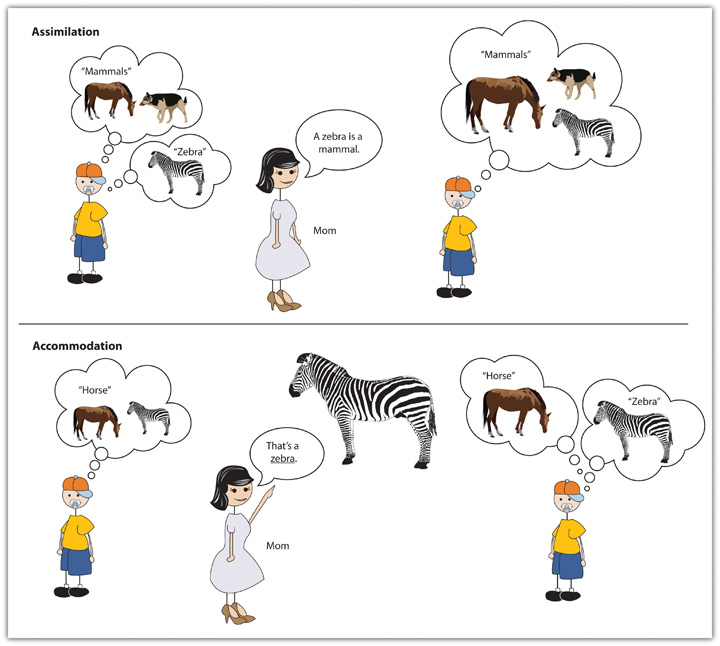

Accommodation: Learning new information and thus changing the schema.

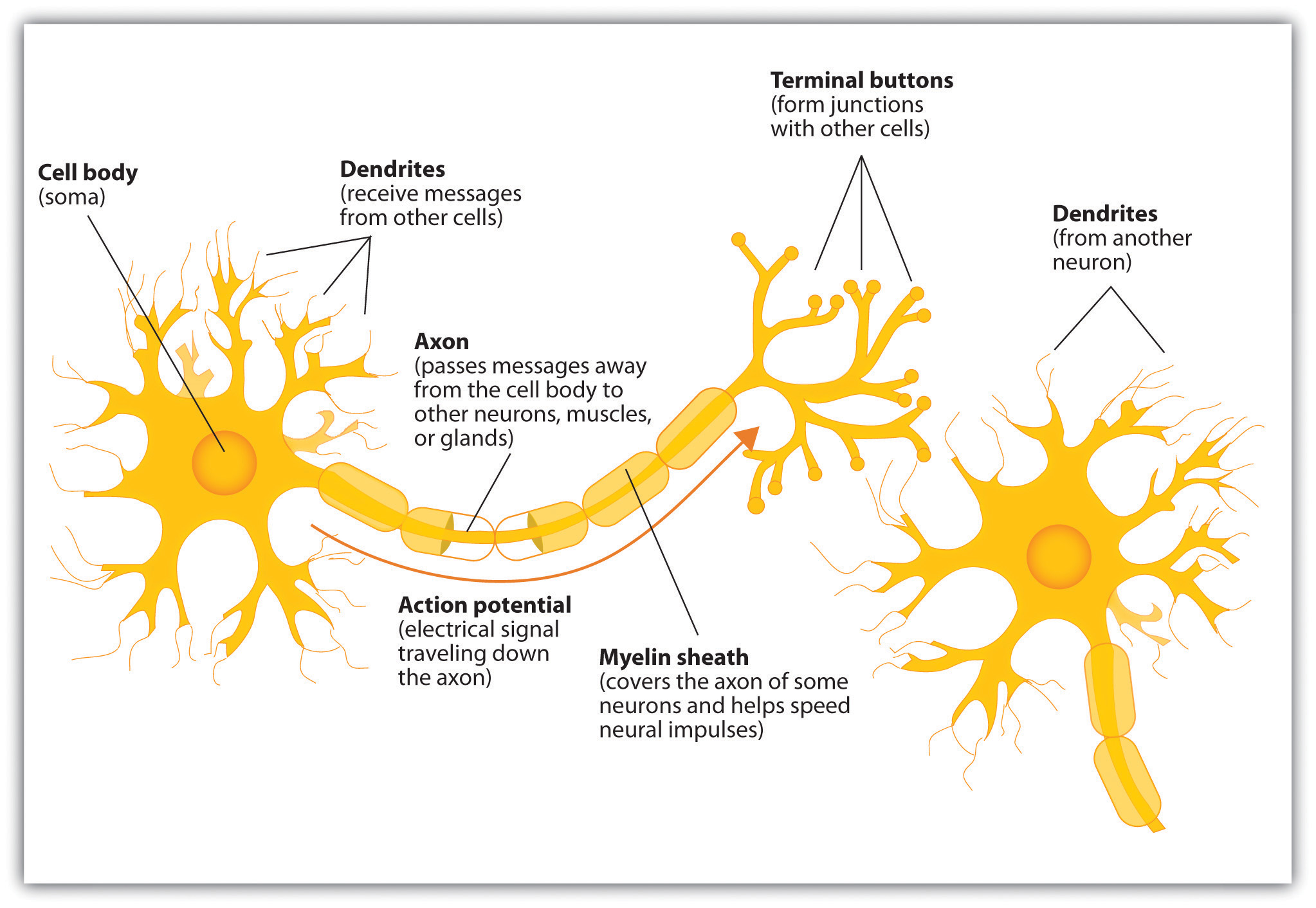

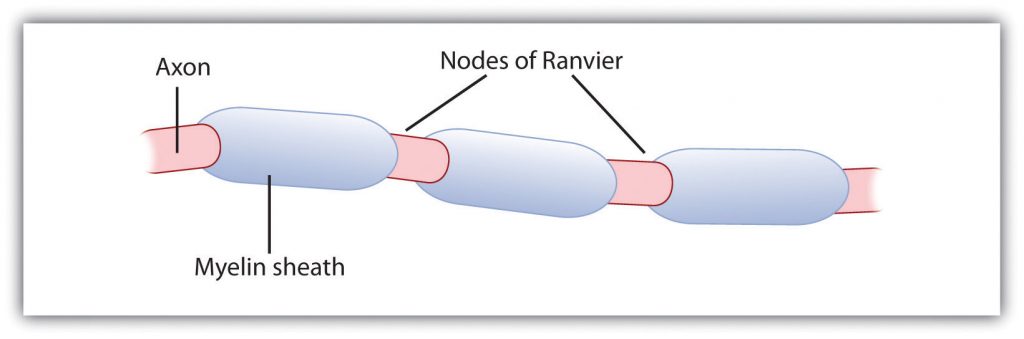

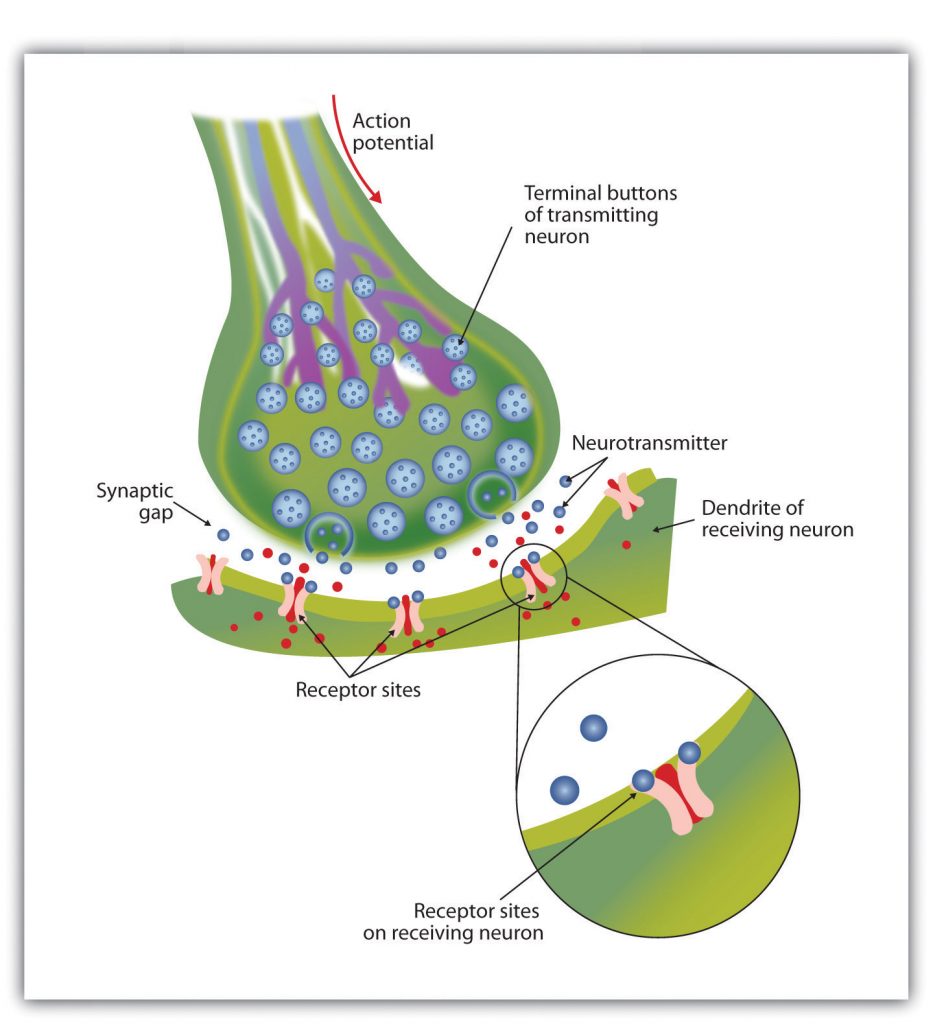

Action Potential: The change in electrical charge that occurs in a neuron when a nerve impulse is transmitted.

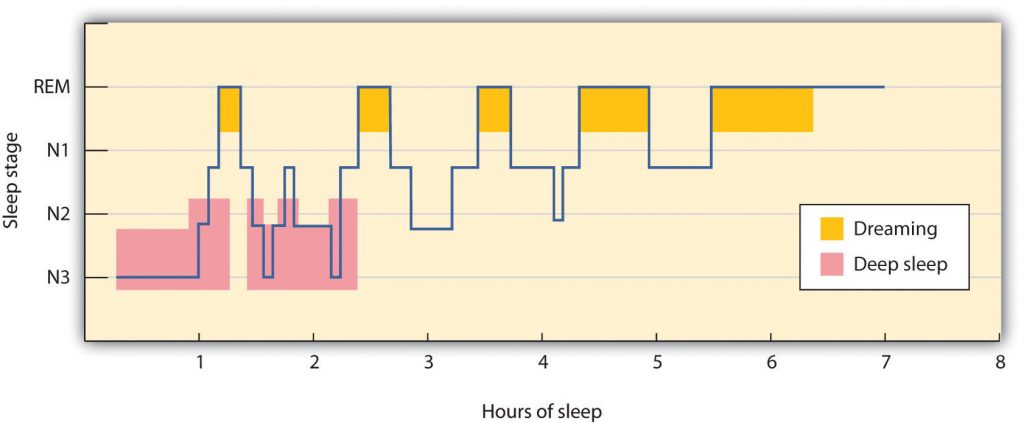

Activation-Synthesis Theory of Dreaming: A prominent neurobiological theory of dreaming that states dreams don’t actually mean anything, and people construct dream stories after they wake up to make sense of nonsensical brain impulses.

Active Imagination: Activating our imaginal processes in waking life in order to tap into the unconscious meanings of our symbols.

Adaptations: Internal mechanisms that are products of natural selection and helped our ancestors get around the world, survive, and reproduce. Evolved solutions to problems that historically contributed to reproductive success.

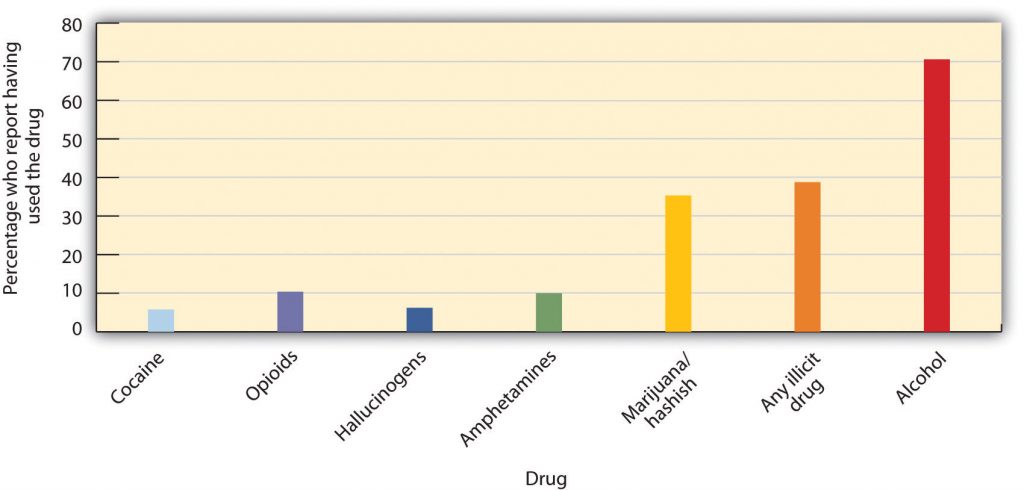

Addiction: When the user powerfully craves the drug and is driven to seek it out, over and over again, no matter what the physical, social, financial, and legal cost.

Adherence: Accurately and regularly following medical orders and recommendations.

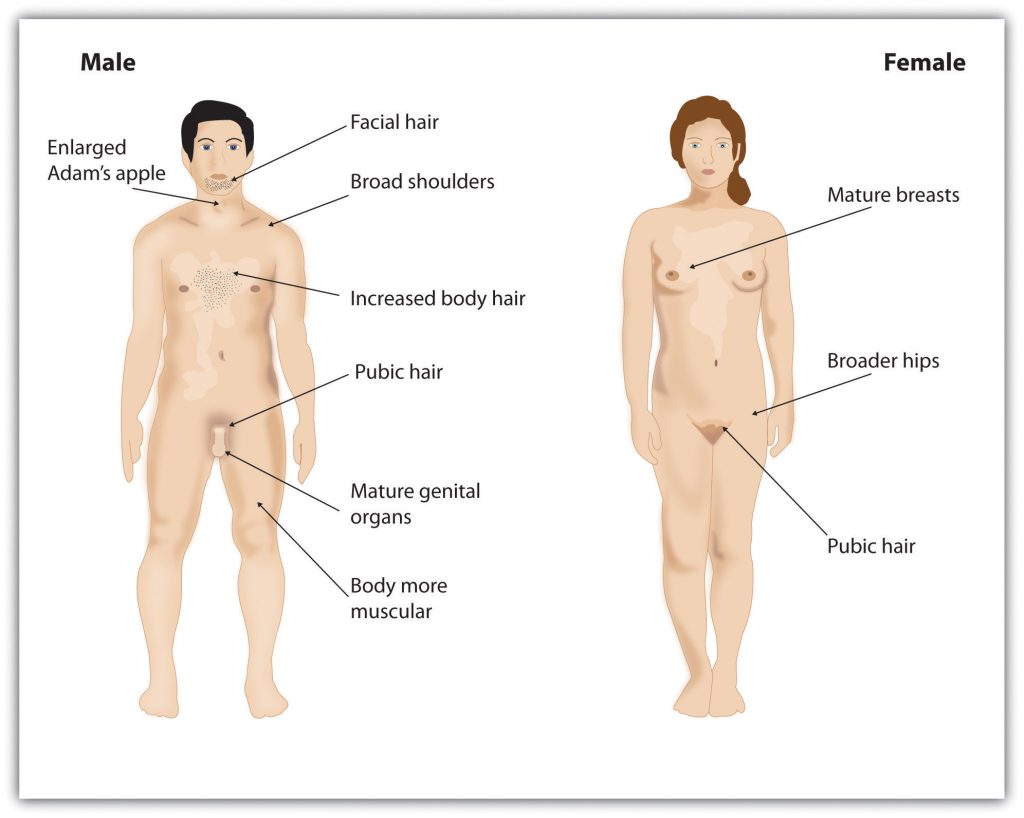

Adolescence: The years between the onset of puberty and the beginning of adulthood.

Adoption Study: A behavior genetic research method that involves comparison of biologically related people, including twins, who have been reared either separately or apart. Often includes a comparison of adopted children to their adoptive and biological parents.

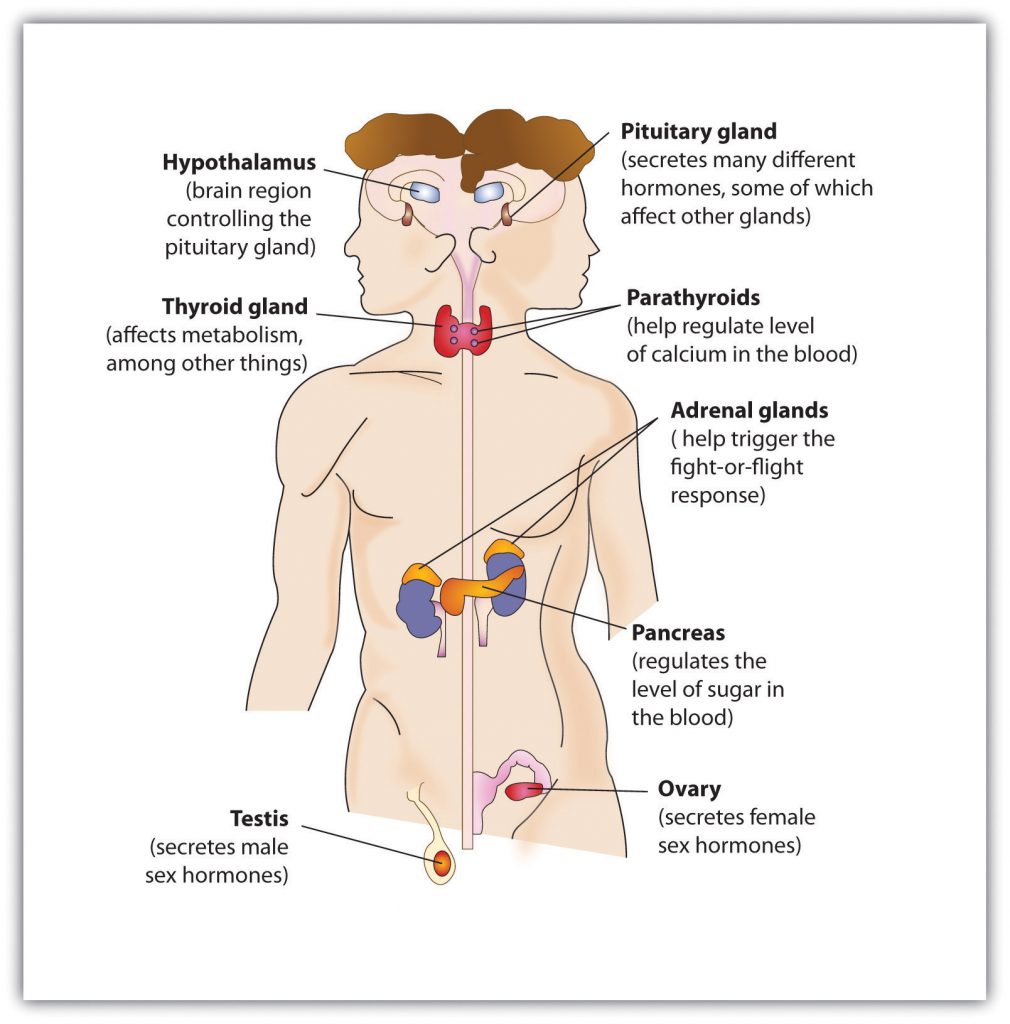

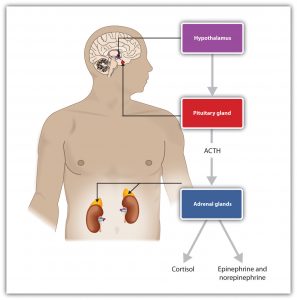

Adrenal Glands: Two triangular glands found atop each kidney. Responsible for the production of hormones that regulate salt and water balance in the body and secrete epinephrine and norepinephrine when a person experiences excitement, threat, or stress. The two glands are also involved in metabolism, the immune system, and sexual development and function.

Adrenaline: A hormone that increases heart rate, elevates blood pressure, and boosts energy supplies.

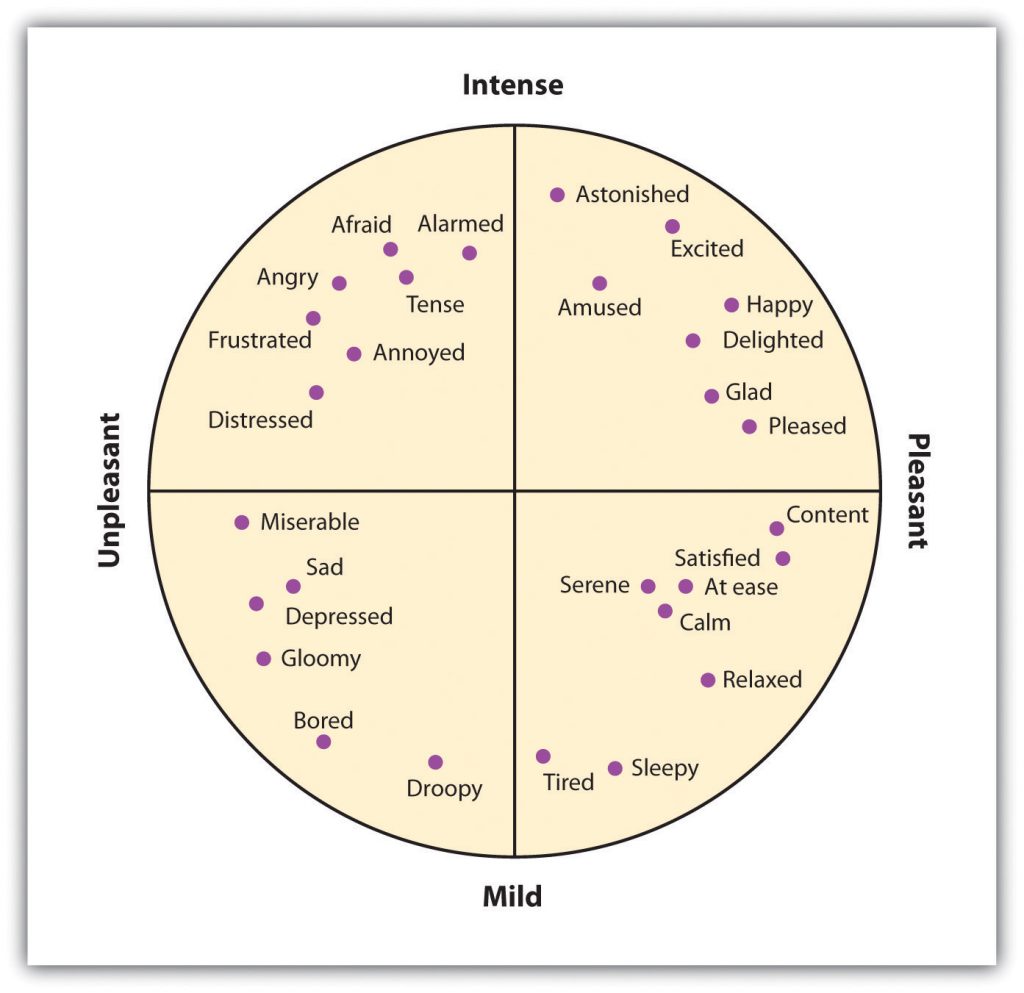

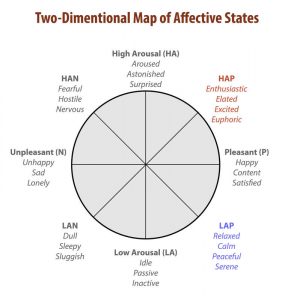

Affect: The experience of a feeling or emotion.

Affective Forecasting: Predictions of one’s future feelings.

Agonist: A drug that has chemical properties similar to a particular neurotransmitter and thus mimics the effects of the neurotransmitter.

Agoraphobia: Anxiety about being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing, or in which help may not be available.

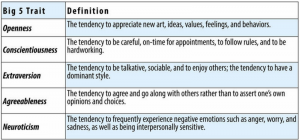

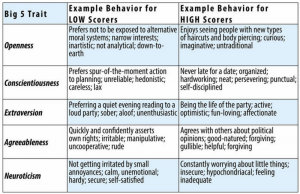

Agreeableness: A core trait that includes dispositional characteristics as being sympathetic, generous, forgiving, and helpful, and behavioral tendencies toward harmonious social relations and likeability. The tendency to agree and go along with others rather than to assert one’s own opinions and choices.

Alcohol: a colorless liquid, produced by the fermentation of sugar or starch, that is the intoxicating agent in fermented drinks.

Altruism: Helping with the aim of improving the wellbeing of others.

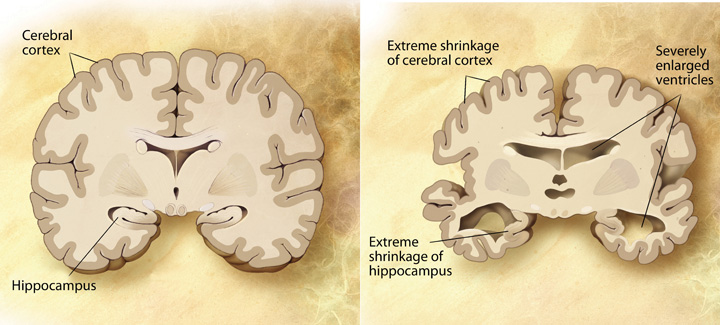

Alzheimer’s Disease: A form of dementia that, over a period of years, leads to a loss of emotions, cognitions, and physical functioning, and that is ultimately fatal.

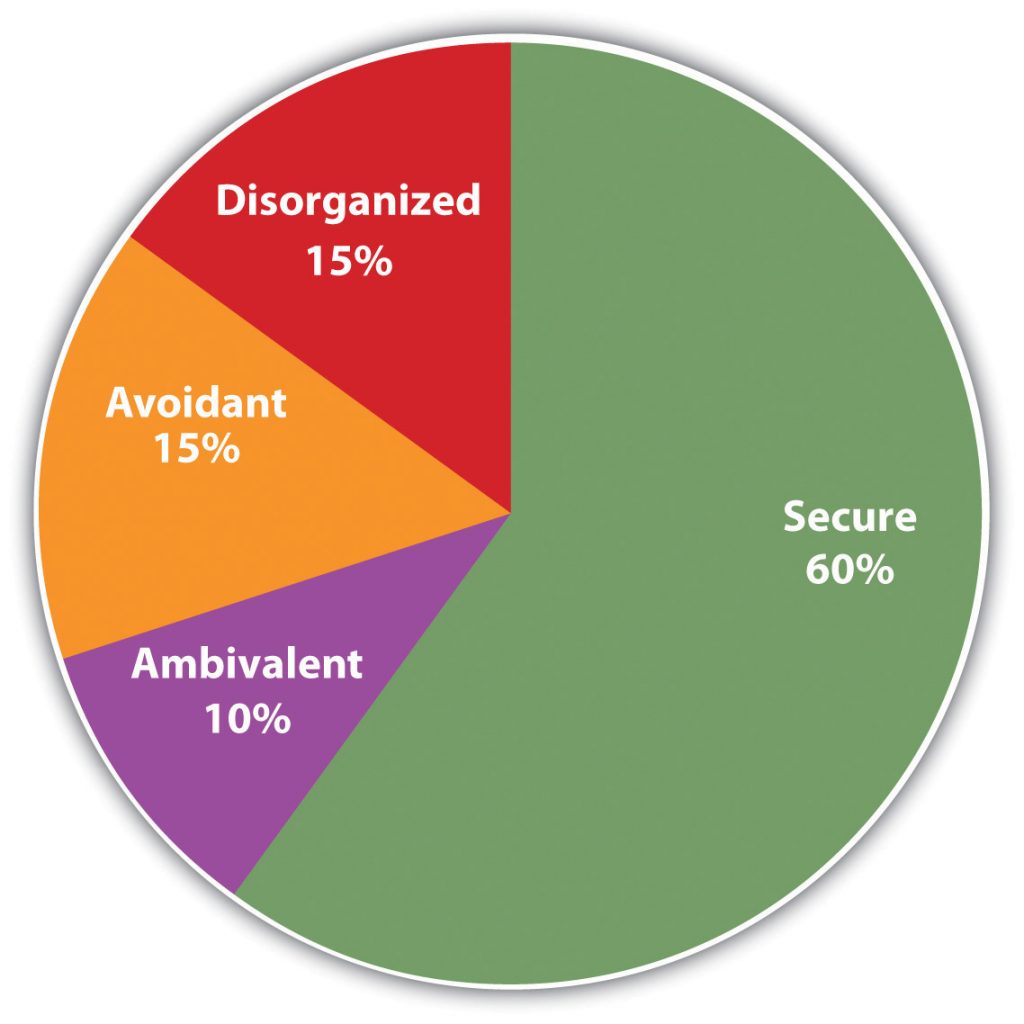

Ambivalent Attachment Style: When a child is wary about the situation in general, particularly the stranger, and stays close or even clings to the mother rather than exploring the toys.

Ambivalent Sexism: Recognizes the complex nature of gender attitudes, in which women are often associated with positive and negative qualities.

Amnesia: a memory disorder that involves the inability to remember information.

Amniotic Sac: The fluid-filled reservoir in which the embryo will live until birth, and which acts as both a cushion against outside pressure and as a temperature regulator.

Amphetamine: a stimulant that produces increased wakefulness and focus, along with decreased fatigue and appetite.

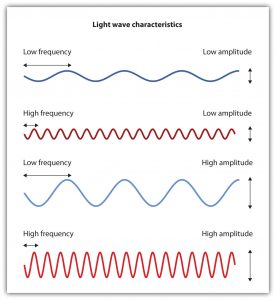

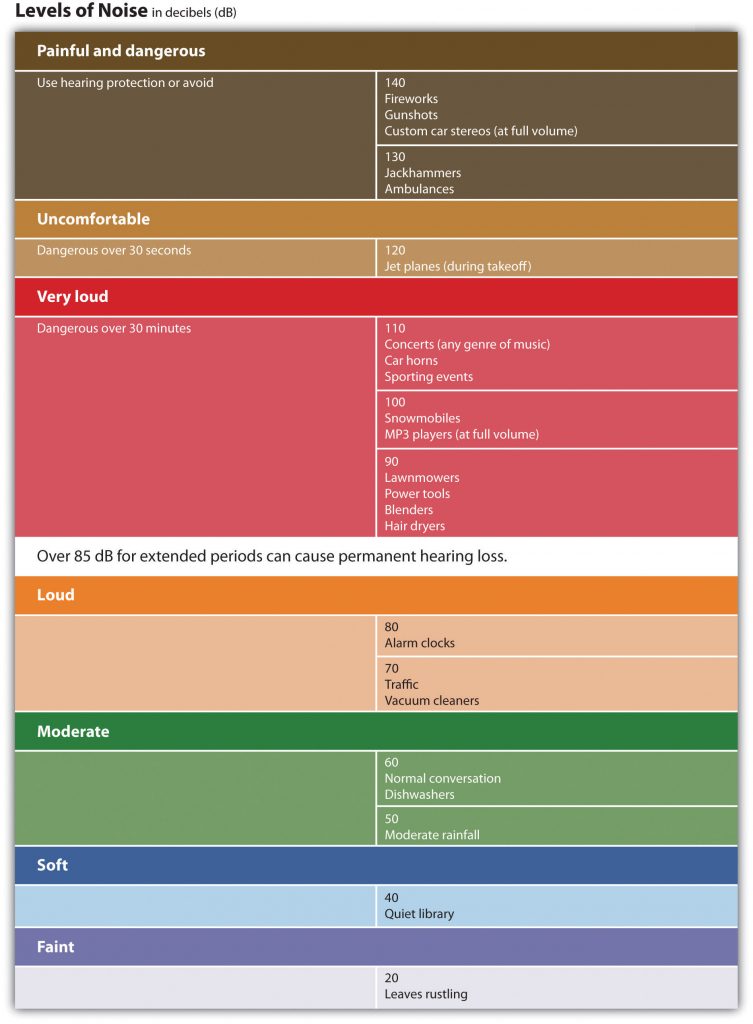

Amplitude: the height of a sound wave. Determines how much energy sound contains.

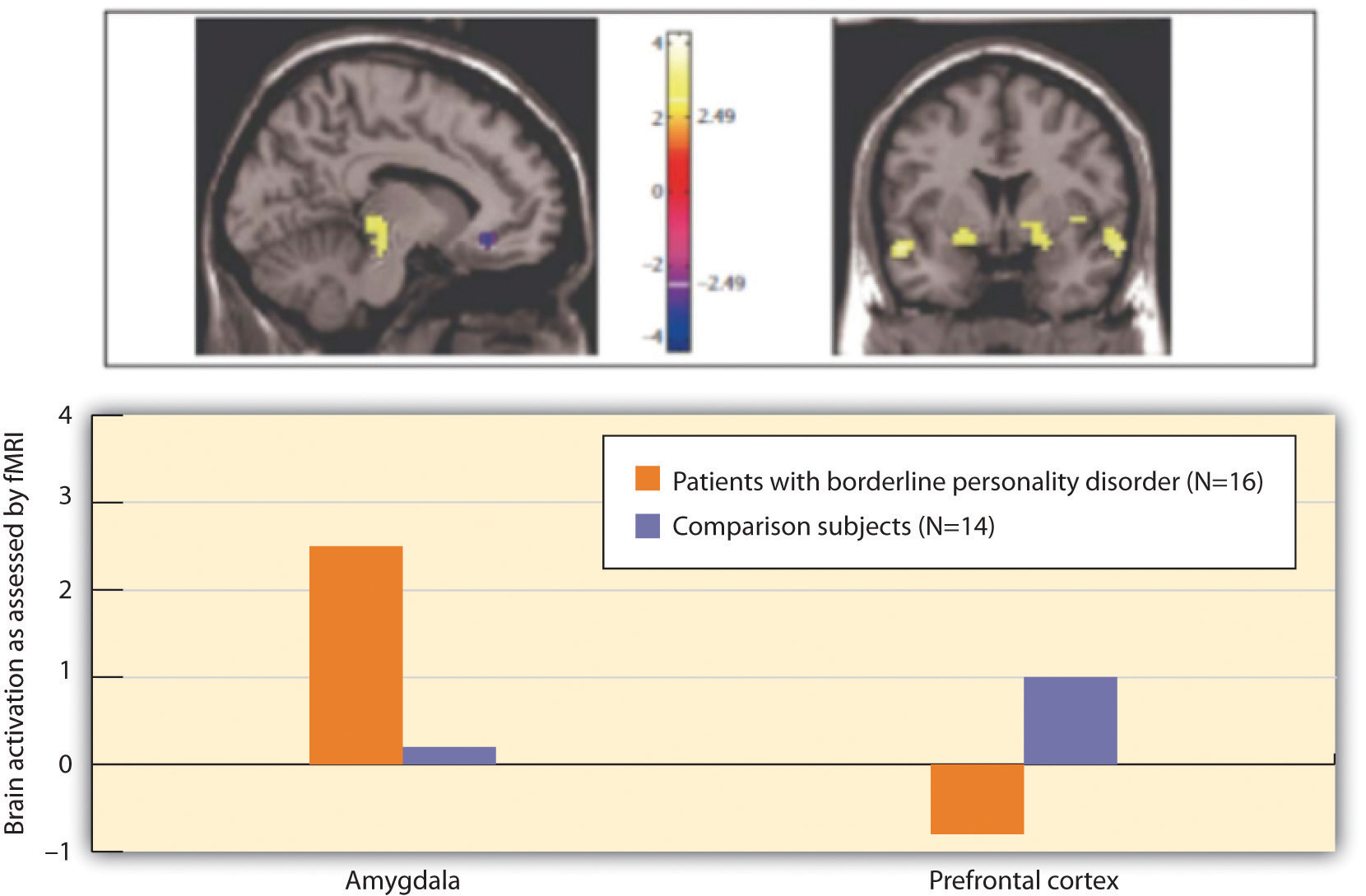

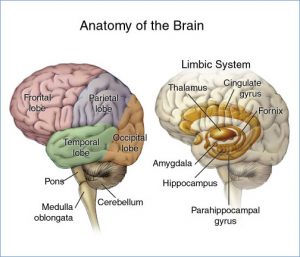

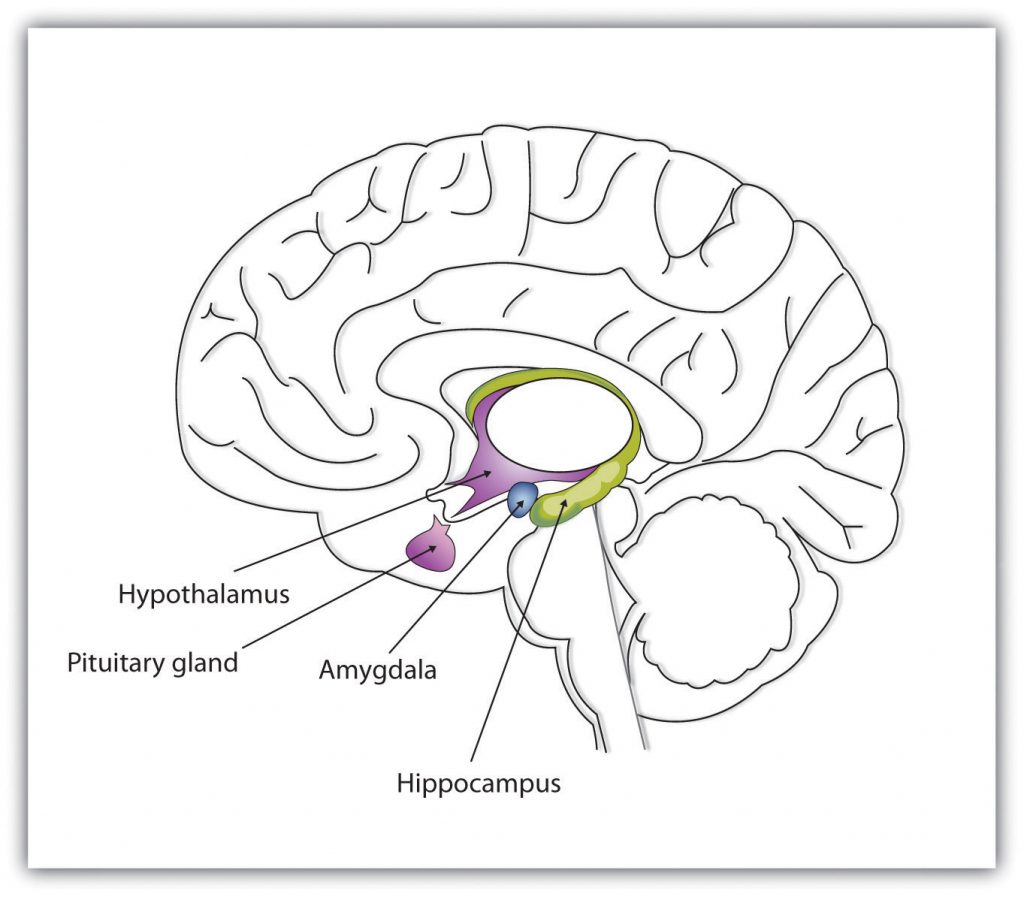

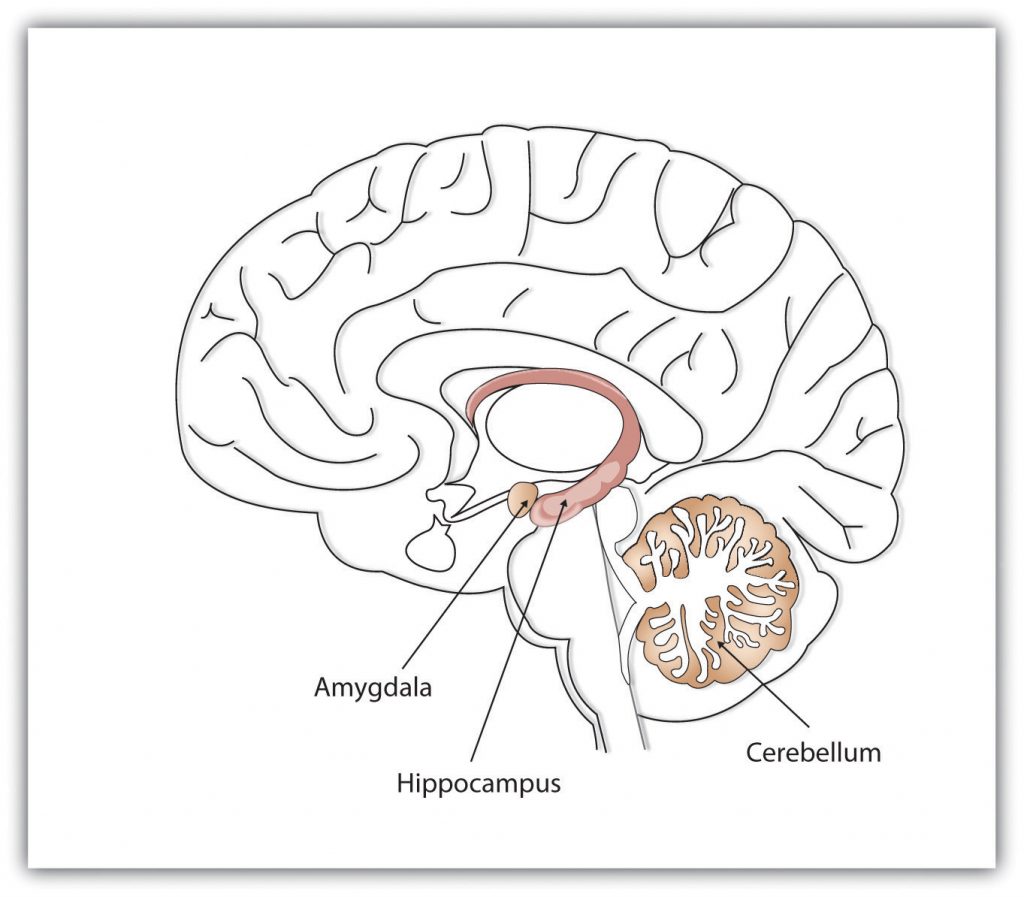

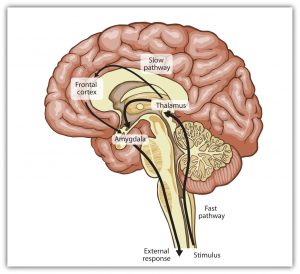

Amygdala: Located within the limbic system. This structure consists of two “almond-shaped” clusters and is primarily responsible for regulating our perceptions of, and reactions to, aggression and fear.

Anchoring: the bias to be affected by an initial anchor, even if the anchor is arbitrary, and to insufficiently adjust our judgments away from that anchor.

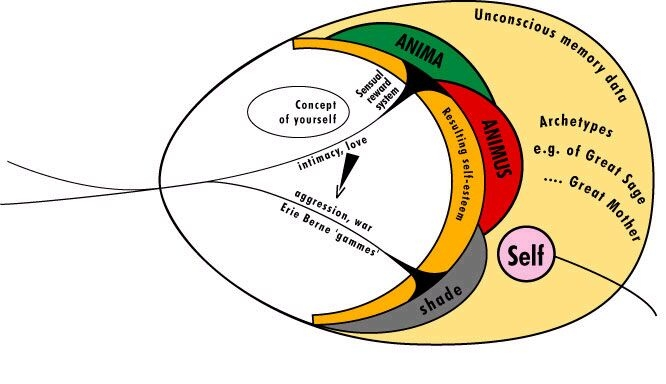

Anima: An archetype symbolizing the unconscious female component of the male psyche.

Animus: An archetype symbolizing the unconscious male component of the female psyche.

Anonymity: protecting a participant’s identity by not collecting or disclosing any personally identifiable information.

Antagonist: A drug that reduces or stops the normal effects of a neurotransmitter.

Anterograde Amnesia: the inability to transfer information from short-term into long-term memory, making it impossible to form new memories after the onset of amnesia.

Antianxiety Medications: Drugs that help relieve fear or anxiety by increasing the action of the neurotransmitter GABA.

Antidepressant Medications: Drugs designed to improve moods.

Antipsychotic Drugs (Neuroleptics): Drugs that treat the symptoms of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders.

Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD): A pervasive pattern of violation of the rights of others that begins in childhood or early adolescence and continues into adulthood.

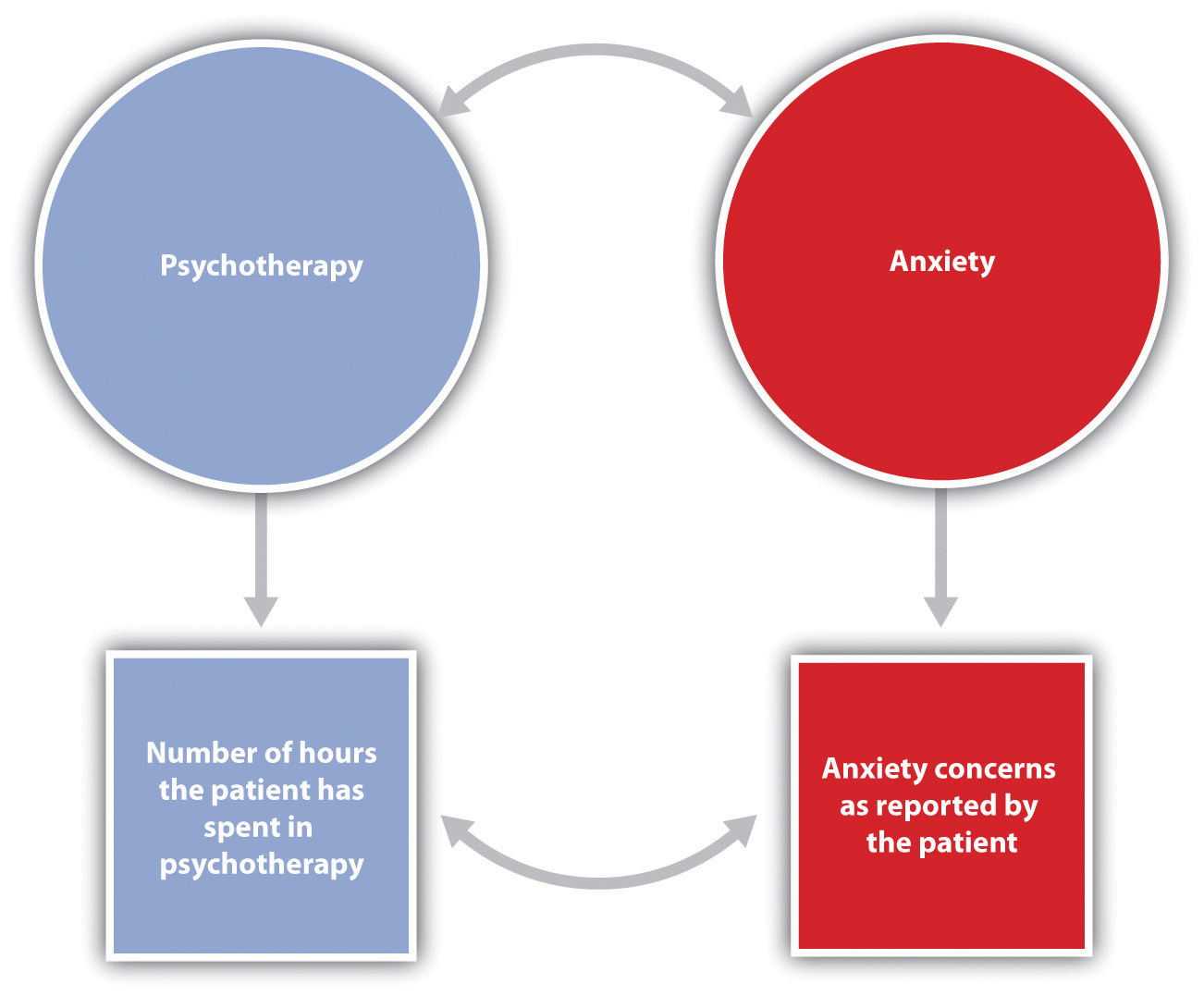

Anxiety Disorders: Psychological disturbances marked by irrational fears, often of everyday objects and situations.

Anxiety: The nervousness or agitation that we sometimes experience, often about something that is going to happen.

APA Ethical Code: a set of 150 ethical standards that psychologists and students in psychology are expected to follow in their activities including clinical work, teaching, and research.

Aphasia: a condition in which language functions are severely impaired.

Applied Research: research that investigates issues that have implications for everyday life and provides solutions to everyday problems.

Appreciation Effects: Having people around us makes us feel good about ourselves.

Aptitude Tests: tests designed to measure one’s ability to perform a given task.

Archetypes: Primordial images that reflect basic patterns or universal themes common to us all.

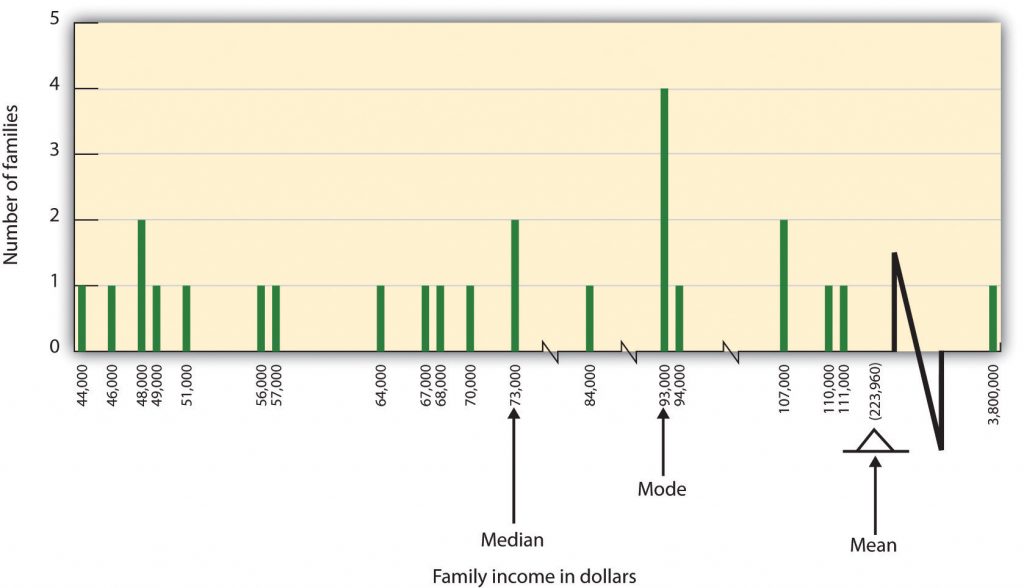

Arithmetic Mean (M): the sum of all the scores of the variable divided by the number of participants in the distribution; Arithmetic Average.

Arousal Cost–Reward Model: Focuses on the aversive feelings aroused by seeing another in need.

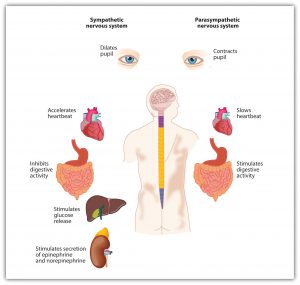

Arousal: Our experiences of the bodily responses created by the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system.

Assimilation: Using already developed schemas to understand new information.

Association Areas: The area within the cortex where sensory and motor information is combined and associated with stored knowledge. Responsible for most of the things that make humans seem human and are involved in higher mental functions, such as learning, thinking, planning, judging, moral reflecting, figuring, and spatial reasoning.

Associative Shifting: It is possible to shift any response from occurring with one stimulus to occurring with another stimulus.

At-Risk Research: research that exposes participants to harm that is greater than that found in everyday circumstances (i.e., greater than minimal risk) and must be reviewed by the full Institutional Review Board committee.

Attachment: The emotional bonds that we develop with those with whom we feel closest, and particularly the bonds that an infant develops with the mother or primary caregiver.

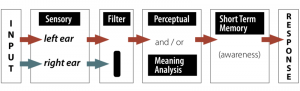

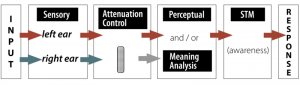

Attention: A state of focused awareness on a subset of the available perceptual information.

Attitudes: Opinions, feelings, and beliefs about a person, concept, or group. Our evaluations of things that can bias us toward having a particular response to it.

Attraction: Being sexually interested in another person.

Audience Design: constructing utterances to suit the audience’s knowledge.

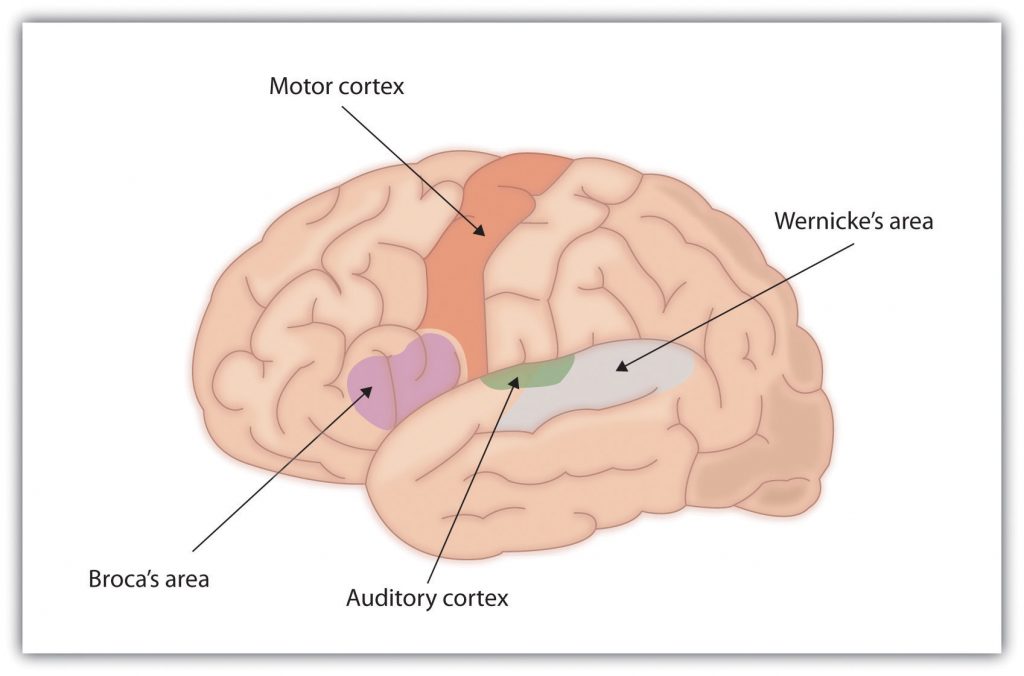

Auditory Cortex: Located in the temporal cortex. Responsible for hearing and language.

Authoethnography: A narrative approach to introspective analysis.

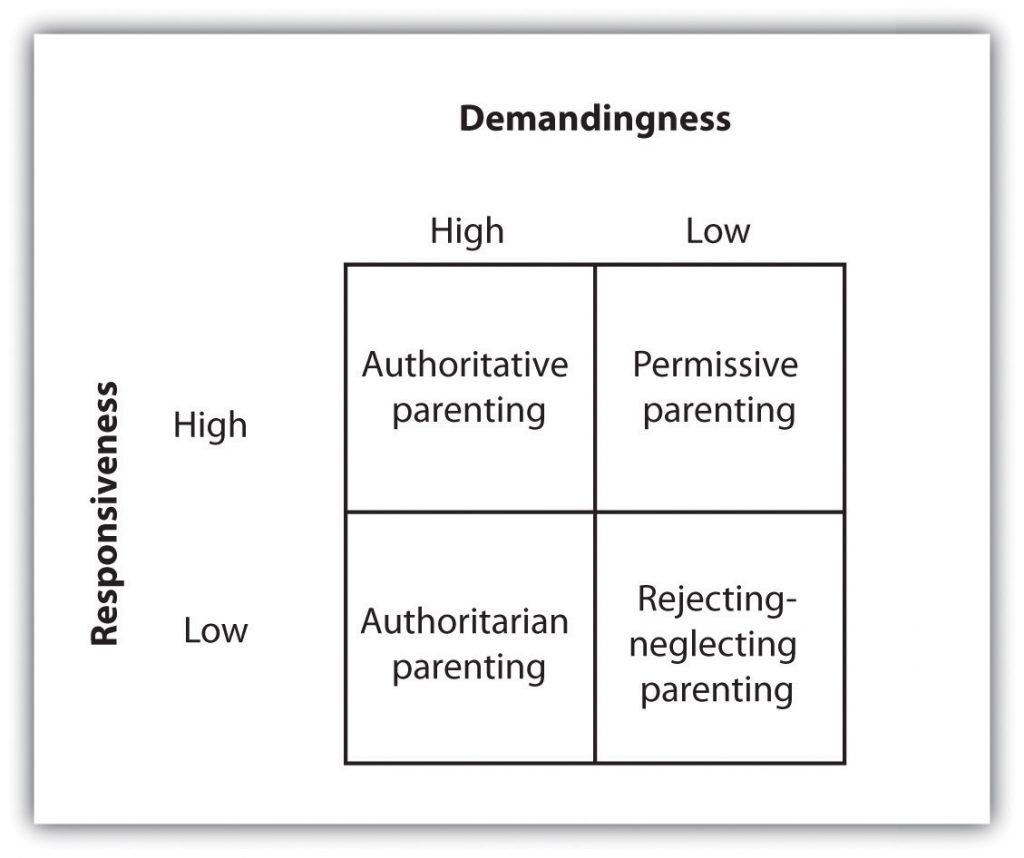

Authoritarian Parents: Demanding but not responsive.

Authoritative Parents: Demanding but they also responsive to the needs and opinions of the child.

Autobiographical Memory: memory for the events of one’s life.

Automatic Behavior: an unconscious behavior that is not self-censored and is typically spontaneous.

Automatic Empathy: a social perceiver unwittingly taking on the internal state of another person, usually because of mimicking the person’s expressive behavior and thereby feeling the expressed emotion.

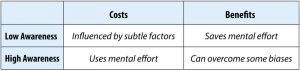

Automatic: A behavior or process that is unintentional, uncontrollable, occurs outside of conscious awareness, or is cognitively efficient.

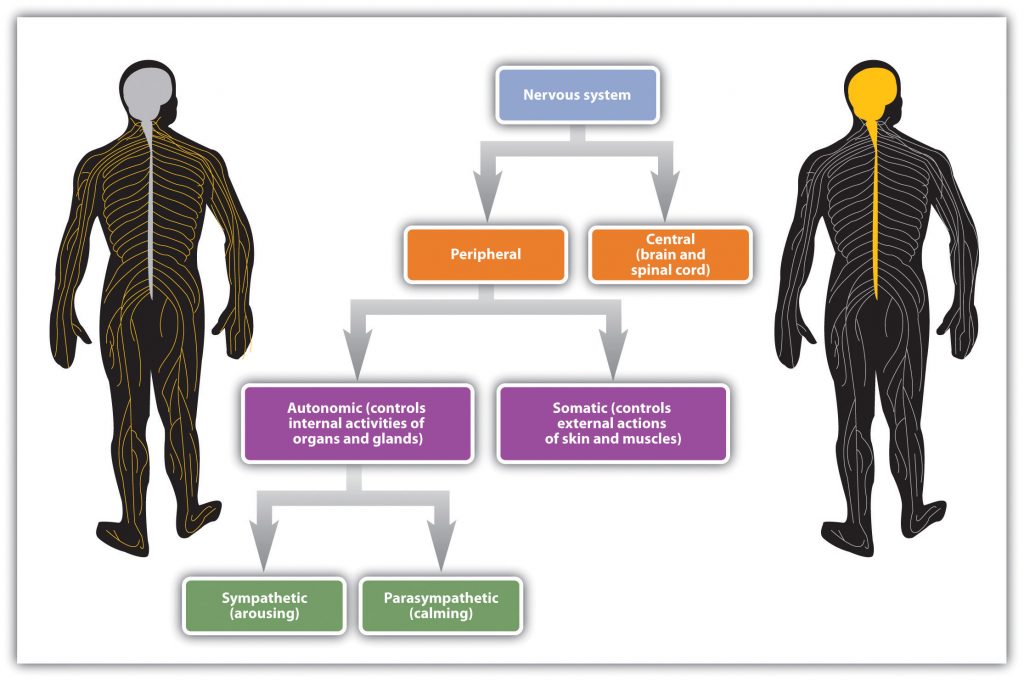

Autonomic Nervous System (ANS): A division of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) that regulates autonomic processes, or internal activities of the human body including heart rate, breathing, digestion, salivation, perspiration, urination, and sexual arousal.

Autonomy: a fundamental right that describes a person’s ability to make his or her own decisions freely without being coerced by others.

Availability Heuristic: the tendency to make judgments of the frequency or likelihood that an event occurs on the basis of the ease with which it can be retrieved from memory.

Availability: The ease of getting a specific response.

Aversion Therapy: A type of behaviour therapy in which positive punishment is used to reduce the frequency of an undesirable behaviour.

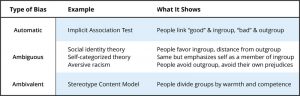

Aversive Racism: The tendency for people to dislike admitting their own racial biases to themselves or others.

Avoidance Learning: A learned response to avoid an unpleasant stimulus or event.

Avoidant Attachment Style: When a child avoids or ignores his or her mother, showing little emotion when the mother departs or returns.

Axon: A long, segmented fibre within the neuron that transmits information away from the cell body toward other neurons or to the muscles and glands.

B

Babbling: the beginning stages of speech. Occurs at about seven months, babies engage in intentional vocalizations that lack specific meaning.

Balance: Putting less effort into a focal goal by working towards other goals.

Barbiturates: depressants that are commonly prescribed as sleeping pills and painkillers.

Basic Research: Research that answers fundamental questions about behavior.

Basic-Level Category: the neutral, preferred category for a given object, at an intermediate level of specificity.

Behavioral Genetics: A variety of research techniques that scientists use to learn about the genetic and environmental influences on human behaviour by comparing the traits of biologically and nonbiologically related family members

Behavioral Medicine: Focuses on the application of research on health predictors and risk factors, or interventions that prevent and treat illness.

Behaviour Therapy: Psychological treatment that is based on principles of learning.

Behaviourism: a school of psychology that is based on the premise that it is not possible to objectively study the mind, and therefore that psychologists should limit their attention to the study of behaviour itself. Focuses on observable behaviour as a means to studying the human psyche.

Belmont Report: a set of federal guidelines created in 1978 after the Tuskegee study that articulates ethical guidelines for research.

Beneficence: an ethical principle from the Belmont Report that emphasizes the importance of maximizing benefits and minimizing harm to research participants and society.

Benevolent Sexism: Refers to the perception that women need to be protected, supported, and adored by men.

Benzodiazepines: a family of depressants used to treat anxiety, insomnia, seizures, and muscle spasms.

Beta Effect: the perception of motion that occurs when different images are presented next to each other in succession.

Bias (i.e., test bias): a test that predicts outcomes better for one group than it does for another.

Biases: the systematic and predictable mistakes that influence the judgment of even very talented human beings.

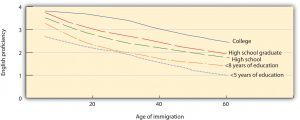

Bilingualism: the ability to speak two languages.

Binocular Depth Cues: depth cues that are created by retinal image disparity and require the coordination of both eyes.

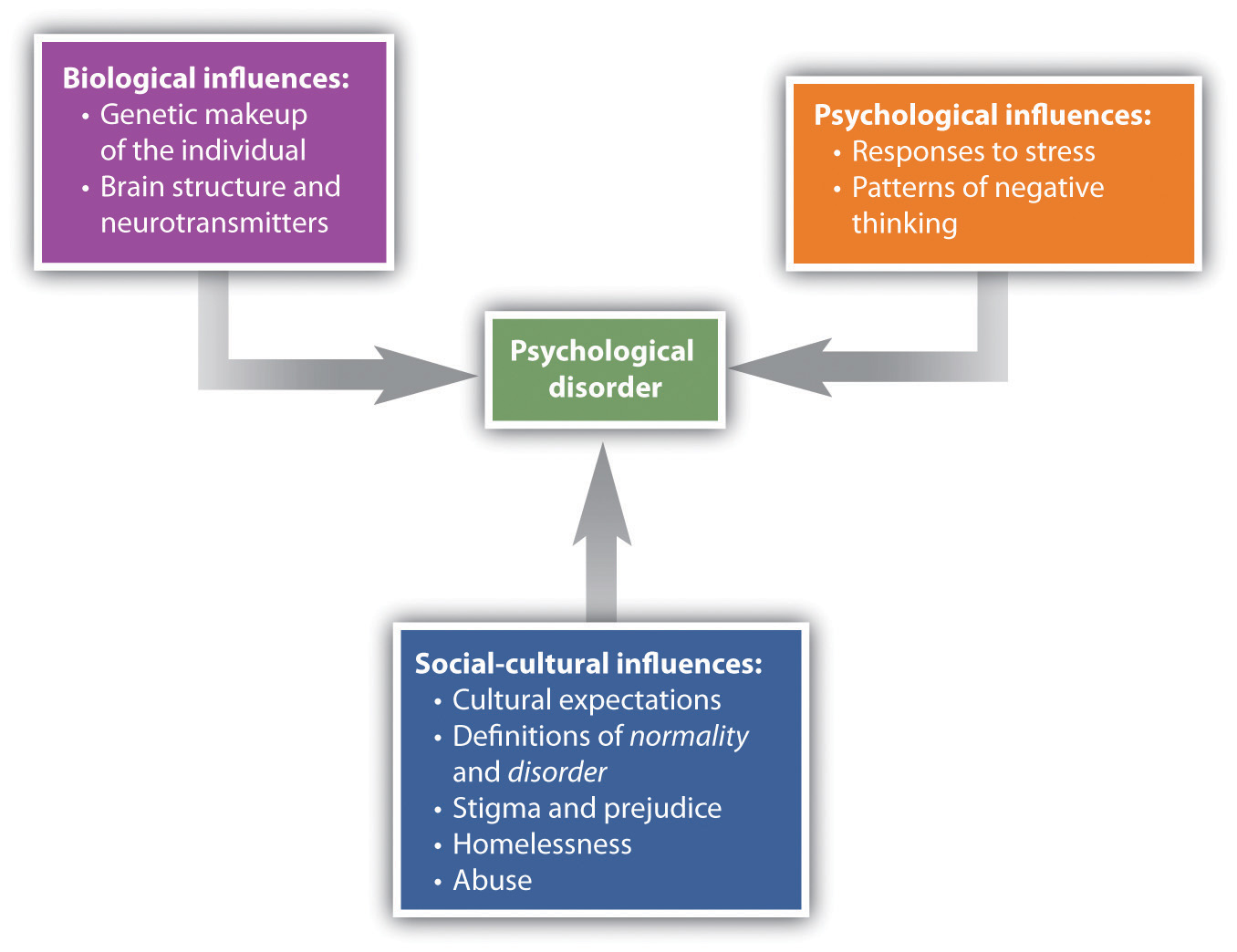

Bio-Psycho-Social Model of Illness: A way of understanding disorder that assumes that disorder is caused by biological, psychological, and social factors.

Biofeedback: A stress reduction technique where the individual is shown bodily information that is not normally available to them, and then taught strategies to alter this signal.

Biological Drive: A drive powering human behaviour including hunger, thirst, and intimacy.

Biological Psychology: School of psychology interested in measuring biological, physiological, or genetic variables in an attempt to relate them to psychological or behavioural variables.

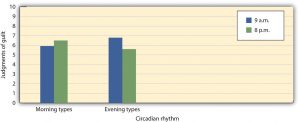

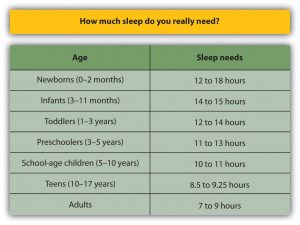

Biological Rhythms: regularly occurring cycles of behaviours.

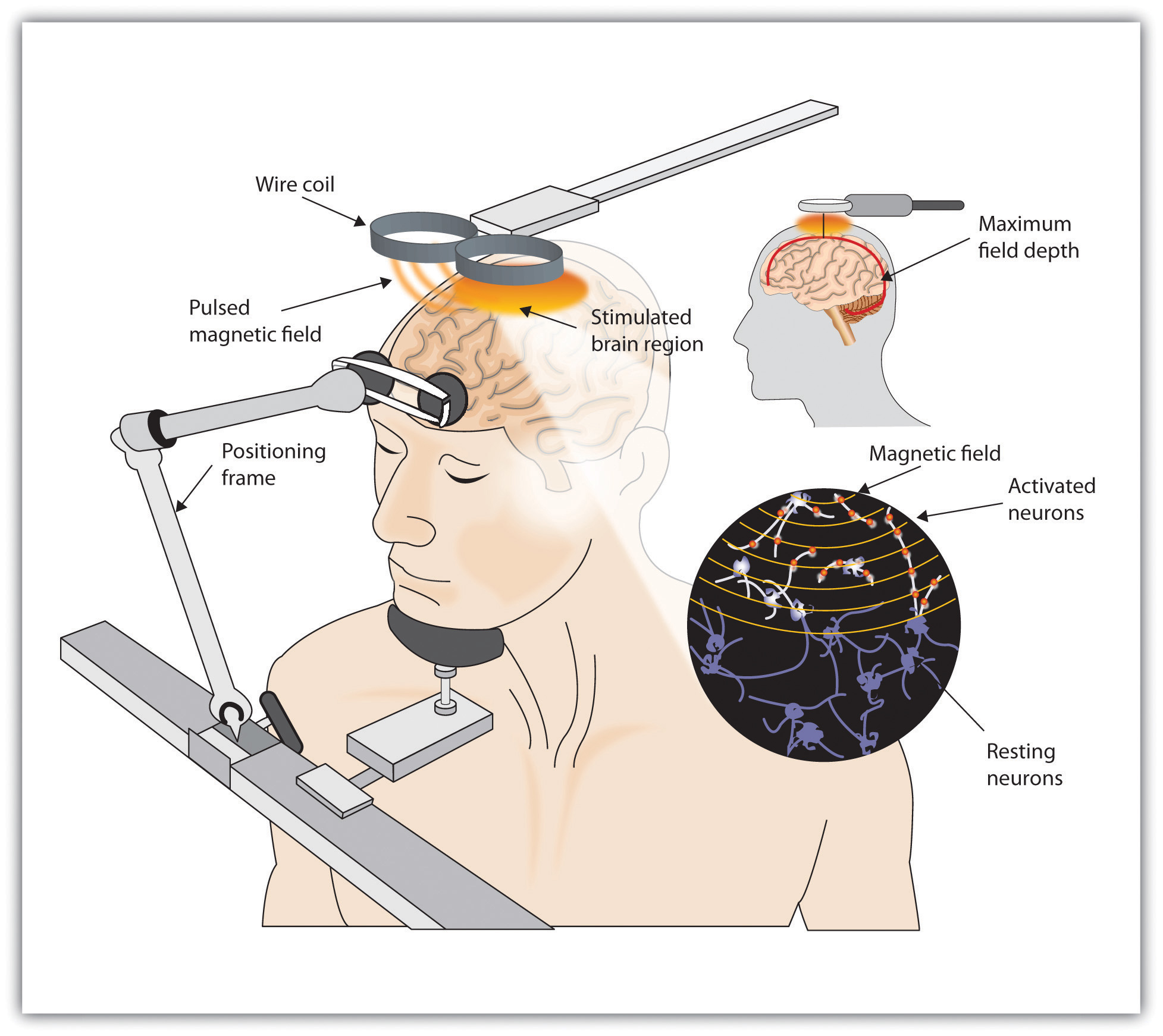

Biomedical Approach to Reducing Disorders: An approach that is based on the use of medications to treat mental disorders as well as the employment of brain intervention techniques.

Biomedical Model of Health: Posits that physical or pathogenic factors primarily contribute to illness.

Biomedical Therapies: Treatments designed to reduce psychological disorder by influencing the action of the central nervous system.

Biopsychosocial Model of Health: Posits that biology, psychology, and social factors are just as important in the development of disease as biological causes.

Bipolar Disorder: A psychological disorder characterized by swings in mood from overly “high” to sad and hopeless, and back again, with periods of near-normal mood in between.

Black Box Model: An interaction of stimuli, consumer characteristics, decision processes, and consumer responses.

Blatant Biases: Conscious beliefs, feelings, and behavior that people are perfectly willing to admit, which mostly express hostility toward other groups while unduly favoring one’s own group.

Blind Spot: a hole in one’s vision due to a lack of photoreceptor cells. Occurs the optic nerve leaves the retina.

Blind to Condition: when the experimenter or the participants do not know which conditions the participants are assigned to.

Blind to the Research Hypothesis: When research participants are not aware of what is being studied.

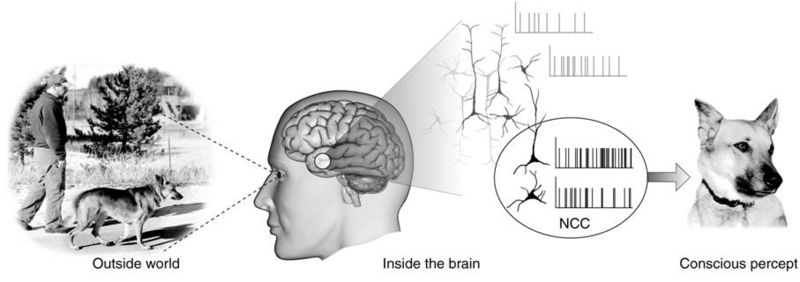

Blindsight: a condition in which people are unable to consciously report on visual stimuli but nevertheless are able to accurately answer questions about what they are seeing.

Blocking: in classical conditioning, the finding that no conditioning occurs to a stimulus if it is combined with a previously conditioned stimulus during conditioning trials. Suggests that information, surprise value, or prediction error is important in conditioning.

Blood Alcohol Content (BAC): a measure of the percentage of alcohol found in a person’s blood. This measure is typically the standard used to determine the extent to which a person is intoxicated, as in the case of being too impaired to drive a vehicle.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): A psychological disorder characterized by a prolonged disturbance of personality accompanied by mood swings, unstable personal relationships, identity problems, threats of self-destructive behaviour, fears of abandonment, and impulsivity.

Bounded Awareness: the systematic ways in which we fail to notice obvious and important information that is available to us.

Bounded Ethicality: the systematic ways in which our ethics are limited in ways we are not even aware of ourselves.

Bounded Rationality: model of human behavior that suggests that humans try to make rational decisions but are bounded due to cognitive limitations.

Bounded Self-Interest: the systematic and predictable ways in which we care about the outcomes of others.

Bounded Willpower: the tendency to place greater weight on present concerns rather than future concerns.

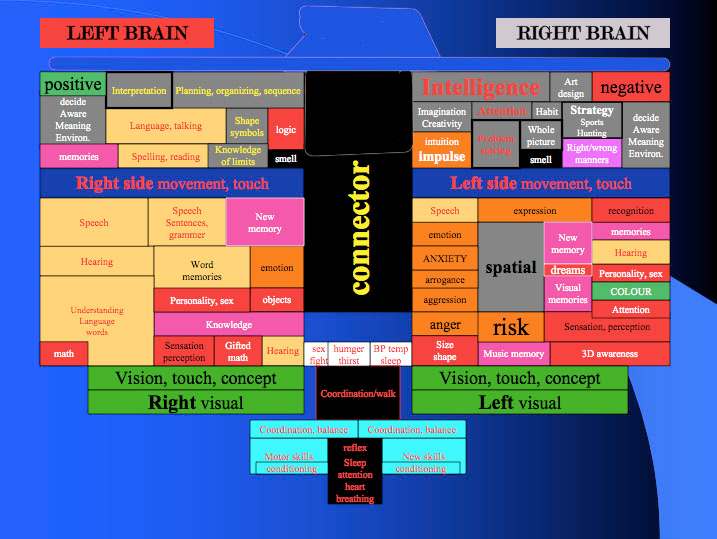

Brain Lateralization: The idea that the left and the right hemispheres of the brain are specialized to perform different functions.

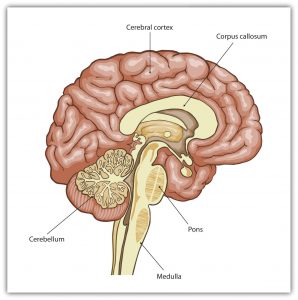

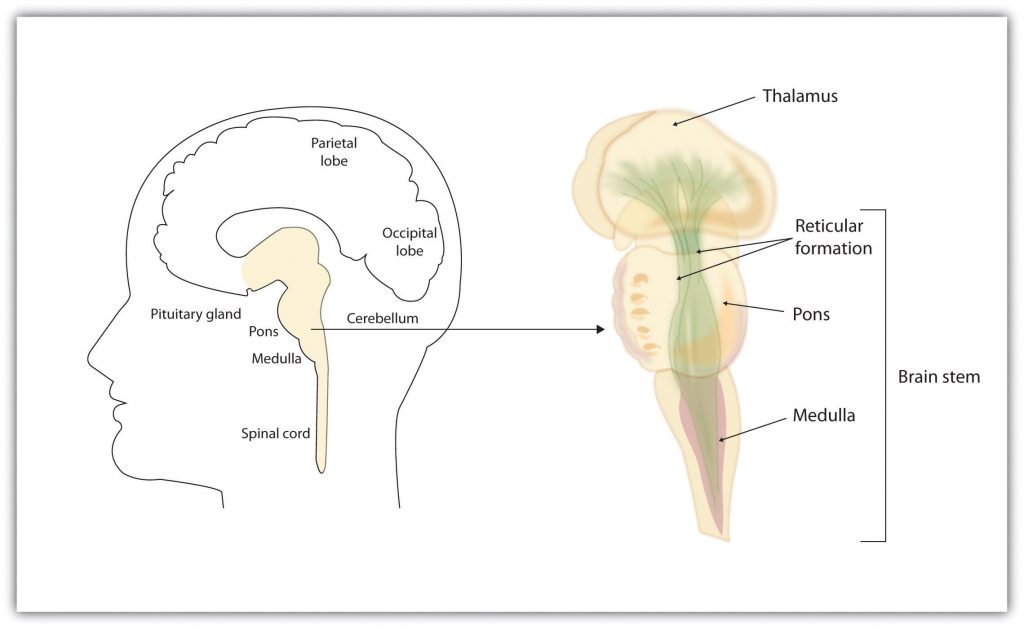

Brain Stem: The oldest and innermost region of the brain that is designed to control the most basic functions of life, including breathing, attention, and motor responses.

Broca’s Area: an area in front of the left hemisphere near the motor cortex responsible for language production.

Bruxism: a sleep disorder in which the sufferer grinds their teeth during sleep.

Bystander Intervention: A phenomenon in which people intervene to help others, including strangers.

C

Caffeine: a bitter psychoactive drug found in the beans, leaves, and fruits of plants.

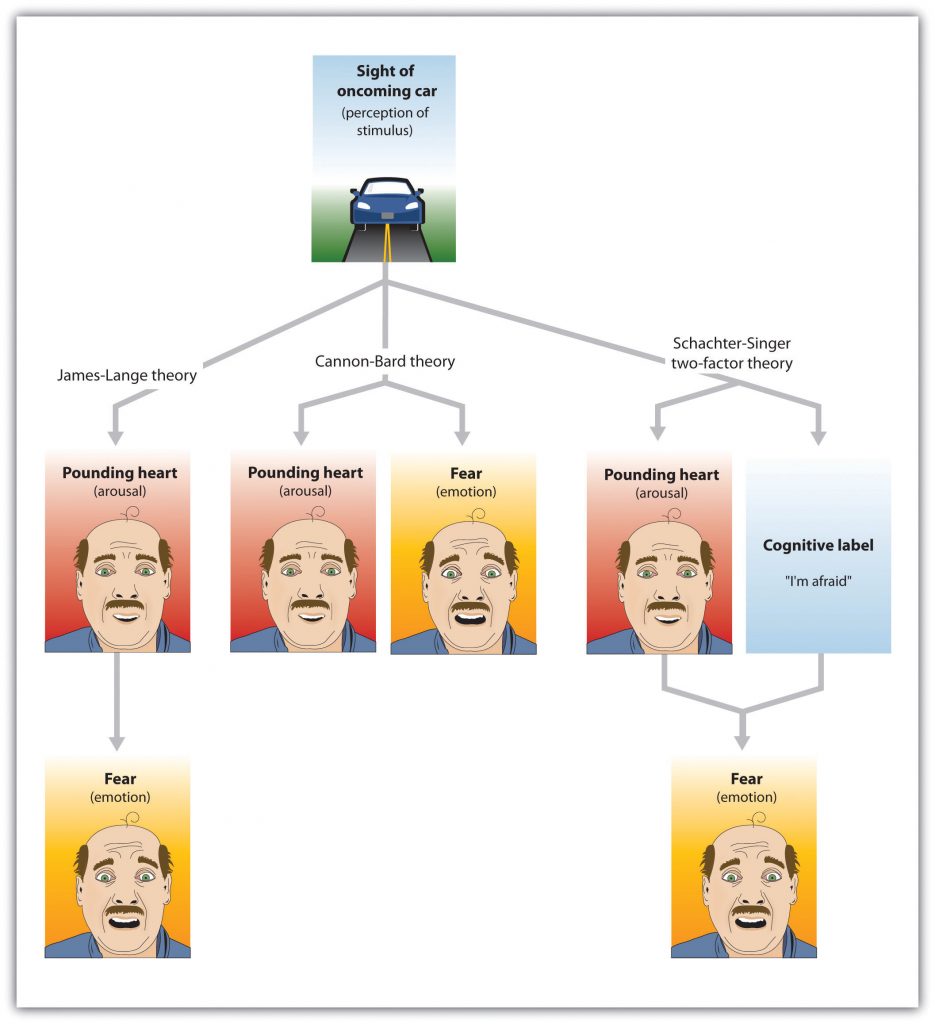

Cannon-Bard Theory of Emotion: A theory proposed by Walter Cannon and Philip Bard that states that the experience of an emotion is accompanied by physiological arousal.

Cartesian Catastrophe: the idea that mental processes taking place outside conscious awareness are impossible.

Case Studies: descriptive records of one or more individual’s experience and behavior.

Cataplexy: a symptom of narcolepsy where an individual loses muscle tone, resulting in a partial or complete collapse.

Categories: networks of associated memories that have features in common with each other – a fundamental part of human nature.

Categorize: to sort or arrange different items into classes or categories.

Category Prototype: the member of the category that is most average or typical of the category.

Category: a set of entities that are equivalent in some way. Usually the items are similar to one another.

Central Executive: the part of working memory that directs attention and processing.

Central Nervous System (CNS): The collection of neurons that make up the brain and the spinal cord. Is the major controller of the body’s functions, charged with interpreting sensory information and responding to it with its own directives.

Central Tendency: the point in the distribution around which the data are centred. Typically measured using the arithmetic mean.

Cerebellum: (i.e., little brain) Consists of two wrinkled ovals behind the brain stem. It functions to coordinate voluntary movement.

Cerebral Cortex: The outer bark-like layer of our brain that allows us to so successfully use language, acquire complex skills, create tools, and live in social groups. The aspect of the brain that sets humans apart from other animals.

Challenge: Seeing change and new experiences as exciting opportunities to learn and develop.

Chameleon Effect: A phenomenon that occurs when individuals nonconsciously mimic the postures, mannerisms, facial expressions, and other behaviors of their interaction partners.

Character Strengths: A psychological and intellectual virtue.

Childhood: The period between infancy and the onset of puberty.

Chromosomes: Multiple strands of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) that are grouped together.

Chronic Disease: Illnesses that persist over time.

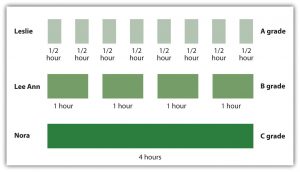

Chunking: the process of organizing information into smaller groupings (chunks), thereby increasing the number of items that can be held in short term memory.

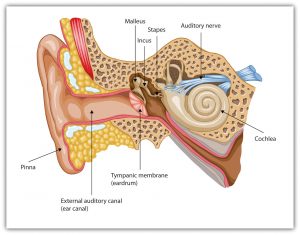

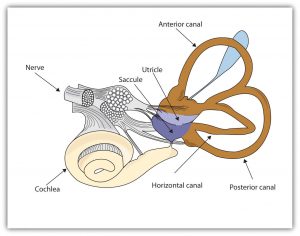

Cilia: a bundle of fibres that are located on each of the hair cells found in the cochlea.

Circadian Rhythm: the strongest and most important biorhythm. It guides the daily waking and sleeping cycle in many animals and is influenced by exposure to sunlight as well as daily schedule and activity. Biologically, it includes changes in body temperature, blood pressure and blood sugar.

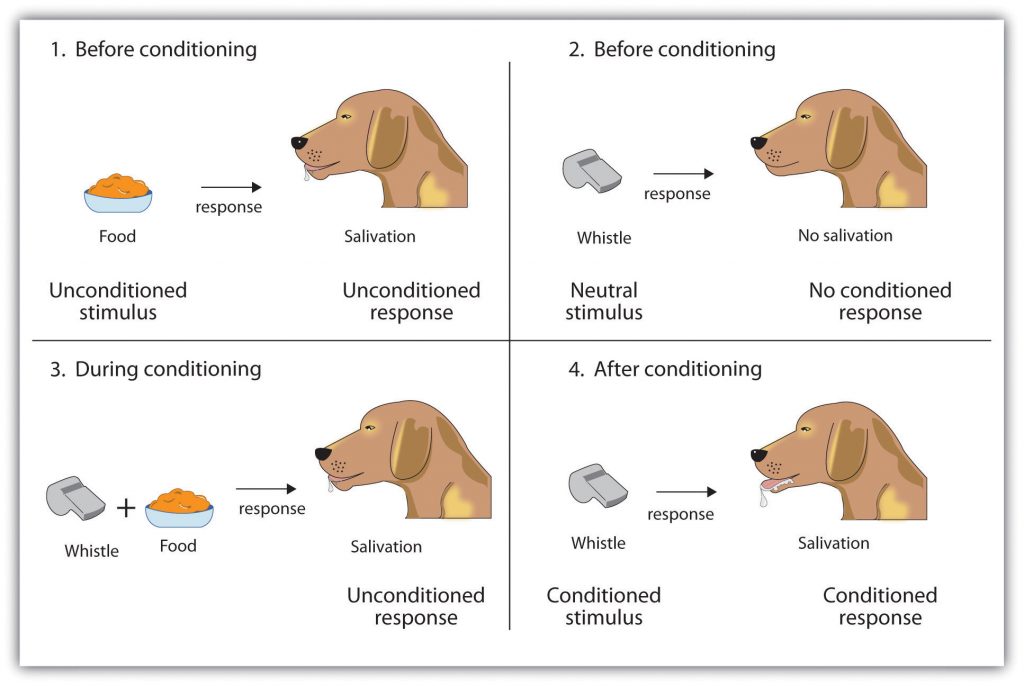

Classical Conditioning Effects: how we learn, often without effort or awareness, to associate neutral stimuli with another stimulus, which creates a naturally occurring response.

Classical Conditioning: A type of learning in which we develop responses to certain stimuli that are not naturally occurring.

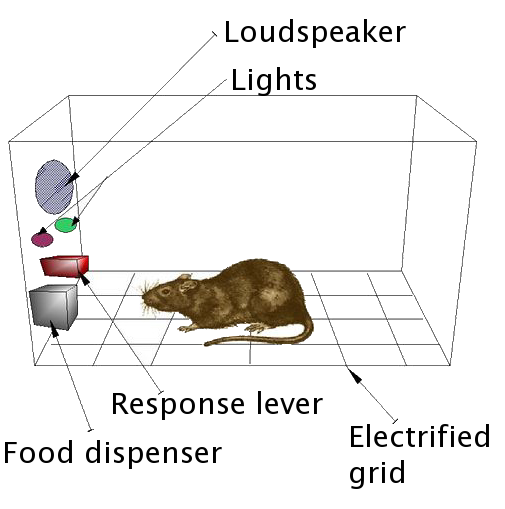

Classical Conditioning: the procedure in which an initially neutral stimulus (the conditioned stimulus, or CS) is paired with an unconditioned stimulus (or US). The result is that the conditioned stimulus begins to elicit a conditioned response (CR). Classical conditioning is nowadays considered important as both a behavioral phenomenon and as a method to study simple associative learning. Same as Pavlovian conditioning. Describes stimulus-stimulus associative learning.

Client- or Person-Centred Therapy: relies on clients’ capacity for self-direction, empathy, and acceptance to promote clients’ development.

Clock Time: the hour on the timepiece that governs the beginning and ending of activities.

Cocaine: an addictive drug obtained from the leaves of the coca plant.

Cochlea: a snail-shaped liquid-filled tube in the inner ear that contains the cilia.

Cochlear Implant: a device made up of a series of electrodes that are placed inside the cochlea.

Cocktail Party Phenomenon: the ability to focus one’s auditory attention on a stimulus while filtering out other competing stimuli.

Codeine: an analgesic that is weaker and less addictive than morphine and heroin. Also a member of the opiate family.

Cognition: the processes of acquiring and using knowledge.

Cognitive Accessibility: the extent to which knowledge is activated in memory, and thus likely to be used in cognition and behavior.

Cognitive Appraisal: The cognitive interpretations that accompany emotions.

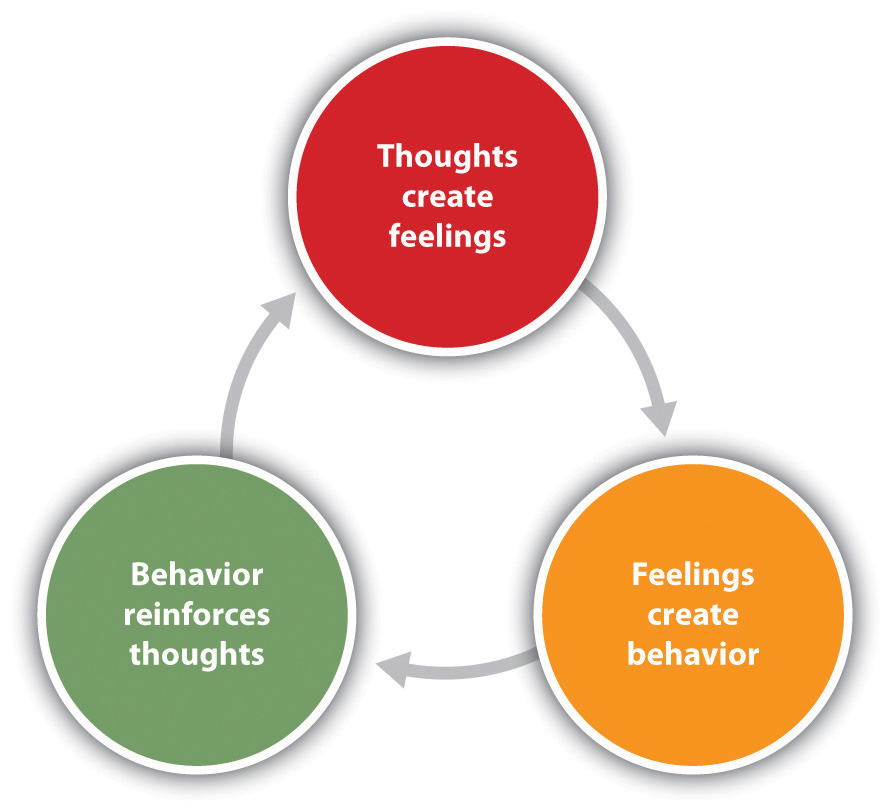

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): A structured approach to treatment that attempts to reduce psychological disorders through systematic procedures based on cognitive and behavioural principles.

Cognitive Biases: errors in memory or judgment that are caused by the inappropriate use of cognitive processes

Cognitive Psychology: A field of psychology that studies mental processes, including perception, thinking, memory, and judgement.

Cognitive Therapy: A psychological treatment that helps clients identify incorrect or distorted beliefs that are contributing to disorder.

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT): Focuses on helping individuals challenge their patterns and beliefs and replace erroneous thinking with more realistic and effective thoughts, thus decreasing self-defeating emotions and behaviour and breaking what can otherwise become a negative cycle.

Cohort Effects: Refer to the possibility that differences in cognition or behaviour at two points in time may be caused by differences that are unrelated to the changes in age.

Collective Unconscious: An aspect of the unconscious that manifests in universal themes that run through all human life.

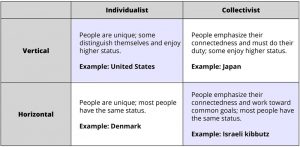

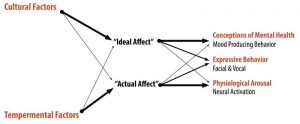

Collectivism: Emphasizes connectedness among people and the importance of working towards common goals. A norm in East Asian cultures that are centered around interdependence, including developing harmonious social relationships with others.

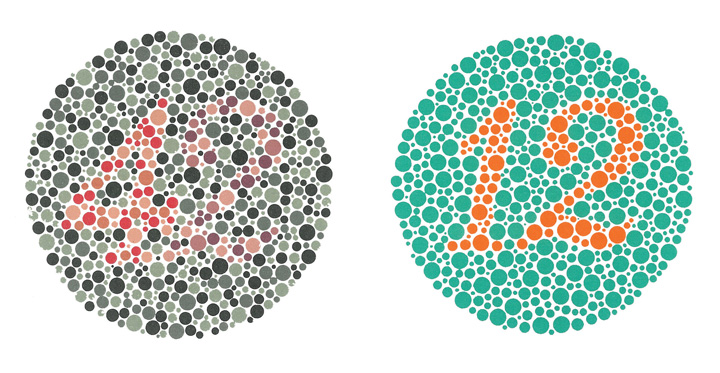

Color Blindness: the inability to detect green and/or red colors.

Commitment: Results from the perceived value and attainability of a goal. The tendency to see the world as interesting and meaningful.

Common Ground: information that is shared by people who engage in a conversation.

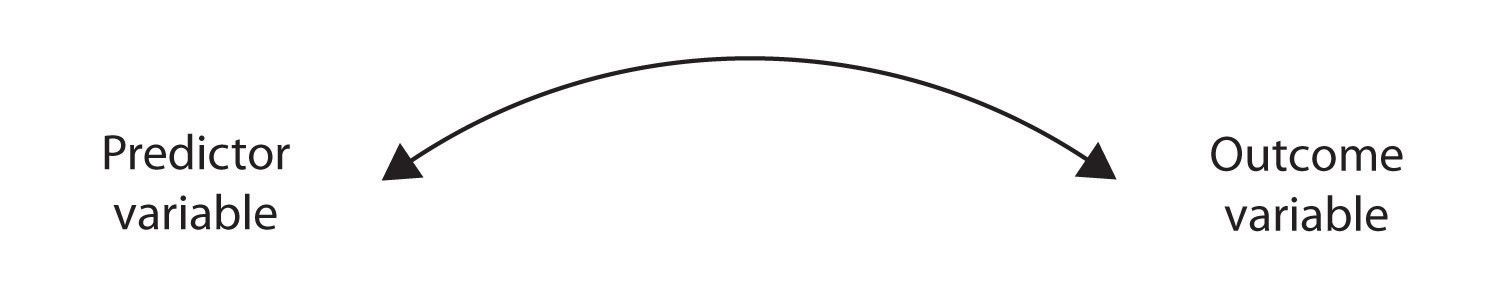

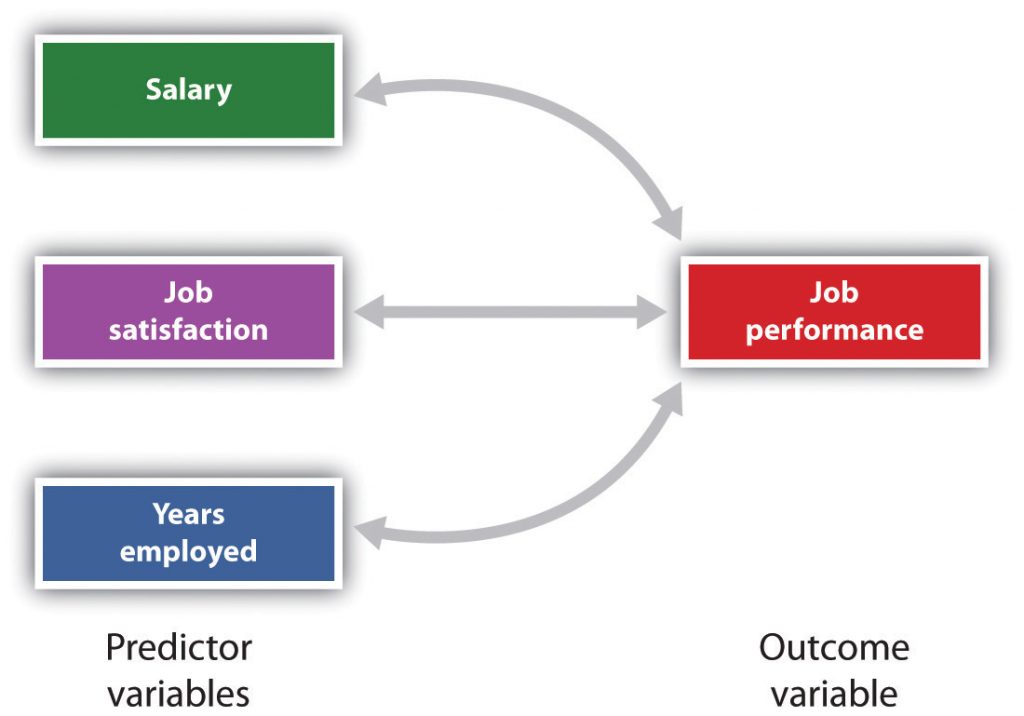

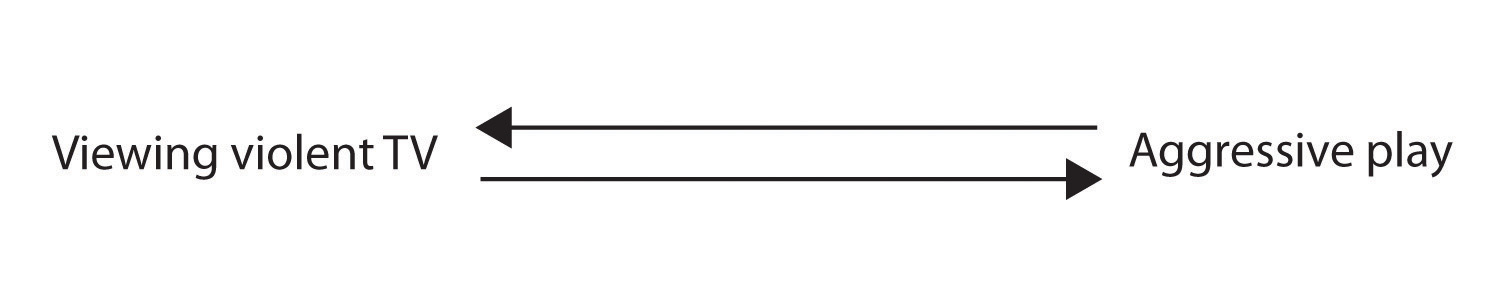

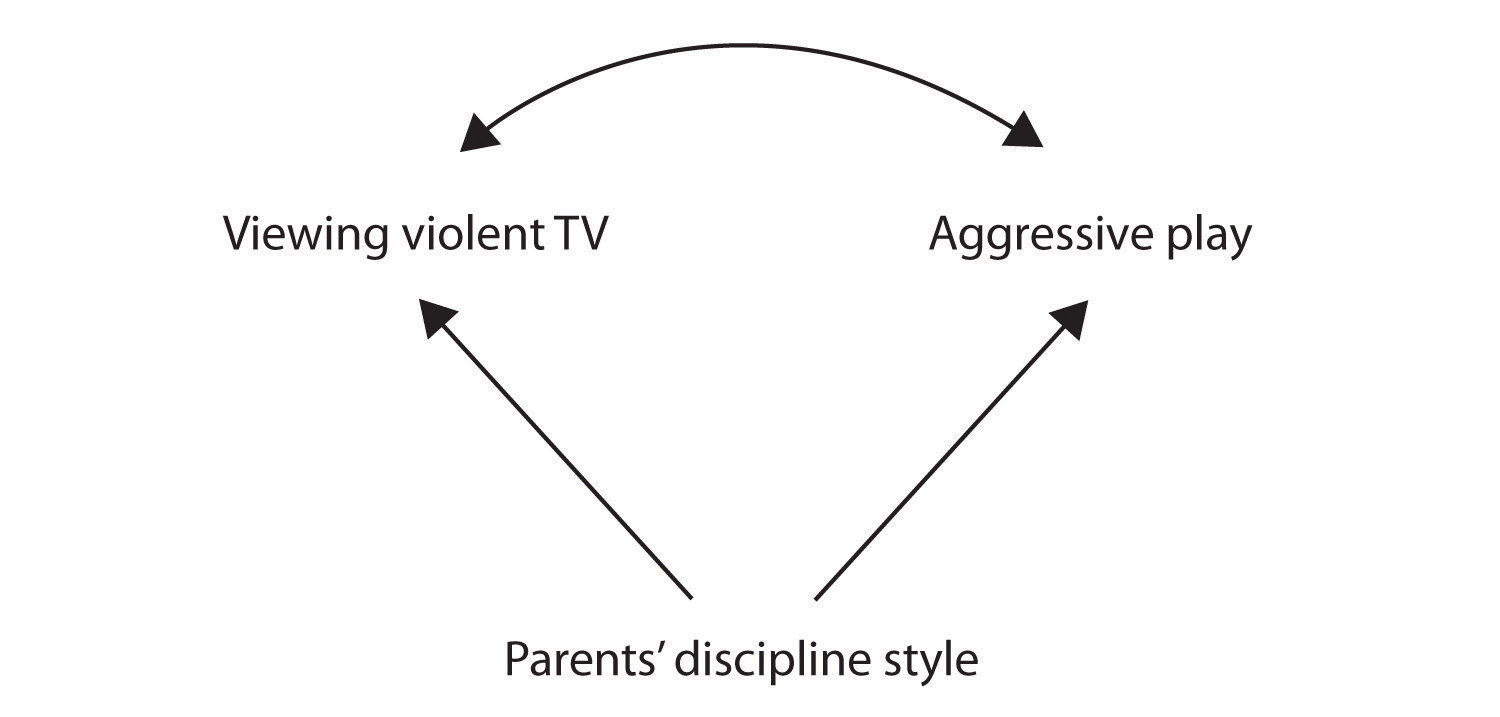

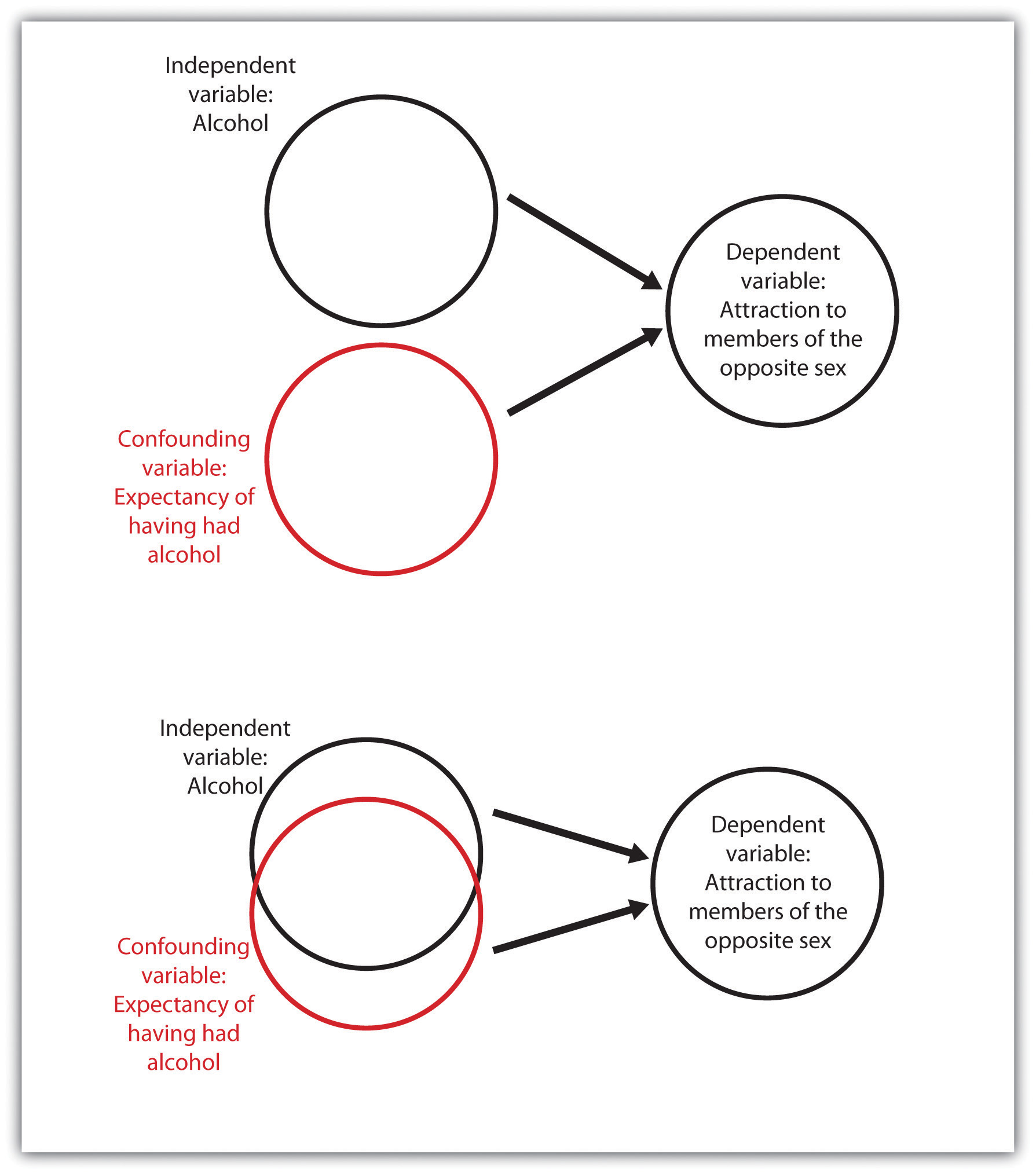

Common-Causal Variable: a variable that is not part of the research hypothesis but that causes both the predictor and the outcome variable and thus produces the observed correlation between them.

Community Learning: Occurs when children serve as both teachers and learners.

Community Mental Health Services: Psychological treatments and interventions that are distributed at the community level.

Comorbidity: Occurs when people who suffer from one disorder also suffer at the same time from other disorders.

Competence: The recognition of one’s own abilities relative to other children.

Complexes: Usually unconscious and repressed emotionally toned symbolic material that is incompatible with consciousness.

Compulsions: Repetitive behaviours.

Concept: the mental representation of a category.

Conception: Occurs when an egg from the mother is fertilized by a sperm from the father.

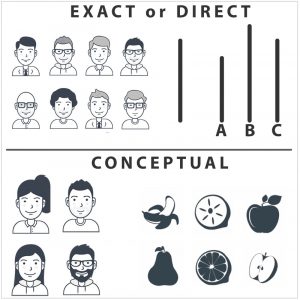

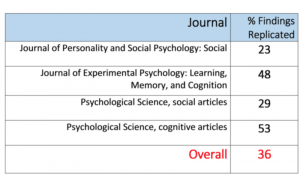

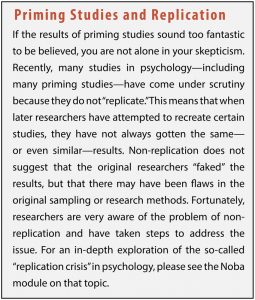

Conceptual Replication: scientific attempt to copy the scientific hypothesis used in an earlier study in an effort to determine whether the results will generalize to different samples, times, or situations. The same – or similar – results are an indication that the findings are generalizable.

Conceptual Variables: abstract ideas that form the basis of research hypotheses.

Concrete Operational Stage: Marked by more frequent and more accurate use of transitions, operations, and abstract concepts.

Conditioned Compensatory Response: in classical conditioning, a conditioned response that opposes, rather than is the same as, the unconditioned response. It functions to reduce the strength of the unconditioned response. Often seen in conditioning when drugs are used as unconditioned stimuli.

Conditioned Response (CR): the response that is elicited by the conditioned stimulus after classical conditioning has taken place.

Conditioned Stimulus (CS): an initially neutral stimulus (like a bell, light, or tone) that elicits a conditioned response after it has been associated with an unconditioned stimulus.

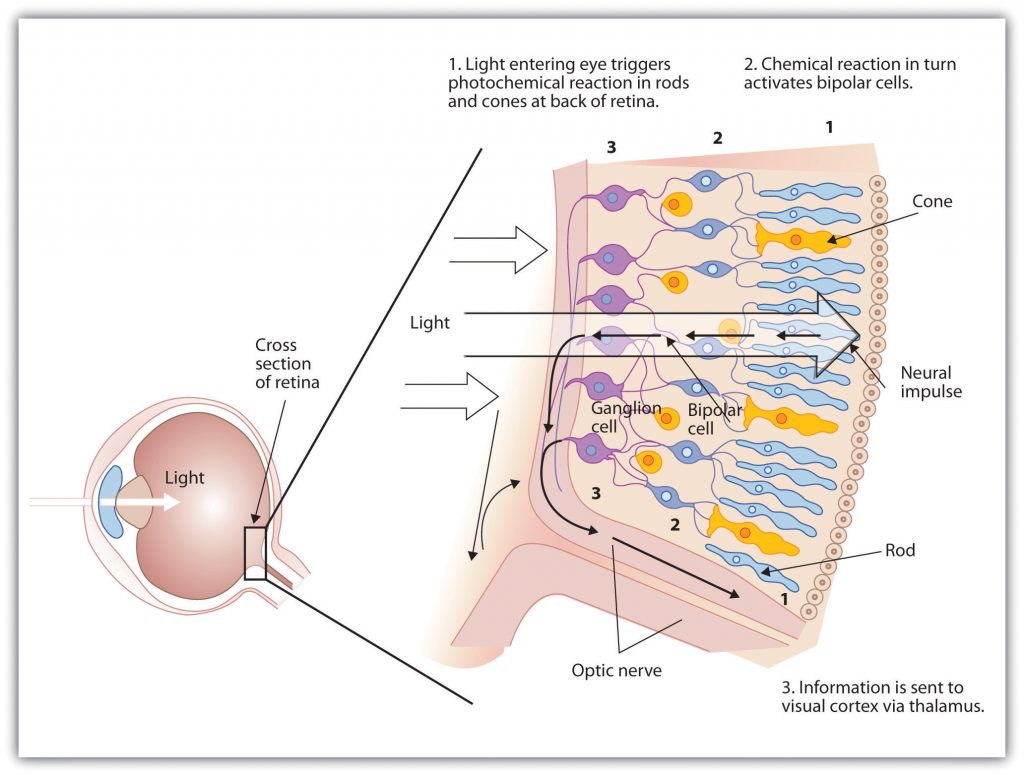

Cones: visual neurons that are specialized in detecting fine detail and colors.

Confederate: An actor working with the researcher. Most often, this individual is used to deceive unsuspecting research participants.

Confidentiality: refers to an agreement between researchers and participants that states that the researcher(s) will not reveal participants’ personal information without their consent or legal authorization.

Confirmation Bias: the tendency to verify and confirm our existing memories rather than to challenge and disconfirm them. A result of our schemas influencing how we seek out and interpret new information. Confirmation bias influences memory in such a way that information that fits our schemas is better remembered than information that disconfirms our schemas.

Conformity: a process in which people change their beliefs and behaviours to be similar to those of the people that they care about.

Conformity: The tendency to act and think like the people around us.

Confounding Variables: variables other than the independent on which the participants in one experimental condition differ systematically from those in the other condition.

Conscientiousness: The tendency to be careful, on-time for appointments, to follow rules, and to be hardworking.

Conscious: Having knowledge of something external or internal to oneself; being aware of and responding to one’s surroundings. The ability to accurately report on a stimuli’s existence (or its nonexistence) more than 50% of the time.

Consciousness: The awareness or deliberate perception of a stimulus. OR our subjective awareness of ourselves and our environment.

Consent Form: a written document in which informed consent is outlined and obtained from clients and participants.

Consolidation: the process occurring after encoding that is believed to stabilize memory traces.

Construct Validity: Tests that actually measure intelligence rather than something else; the extent to which the variables used in the research adequately assess the conceptual variables they were designed to measure.

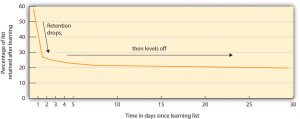

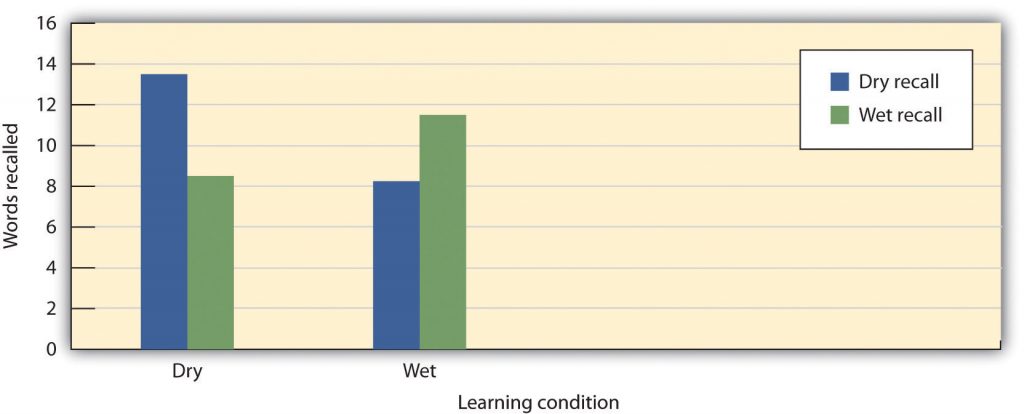

Context-Dependent Learning: an increase in retrieval when the external situation in which information is learned matches the situation in which it is remembered.

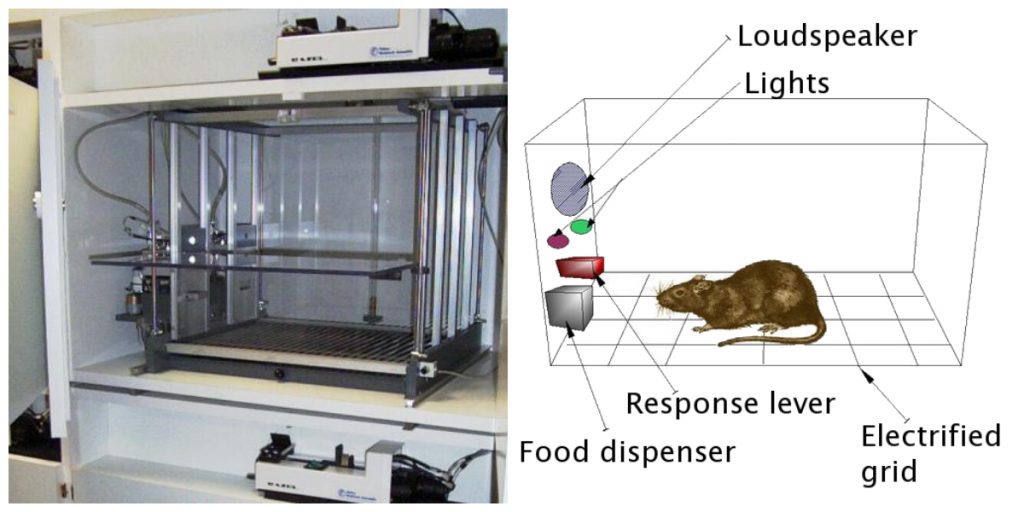

Context: stimuli that are in the background whenever learning occurs. For instance, the Skinner box or room in which learning takes place is the classic example of a context. However, “context” can also be provided by internal stimuli, such as the sensory effects of drugs (e.g., being under the influence of alcohol has stimulus properties that provide a context) and mood states (e.g., being happy or sad). It can also be provided by a specific period in time—the passage of time is sometimes said to change the “temporal context.”

Contextual Information: the information surrounding language that help us interpret language. Examples include the knowledge that we have and that we know that other people have, and nonverbal expressions such as facial expressions, postures, gestures, and tone of voice.

Continual-Activation Theory: Proposes that dreaming is a result of brain activation and synthesis.

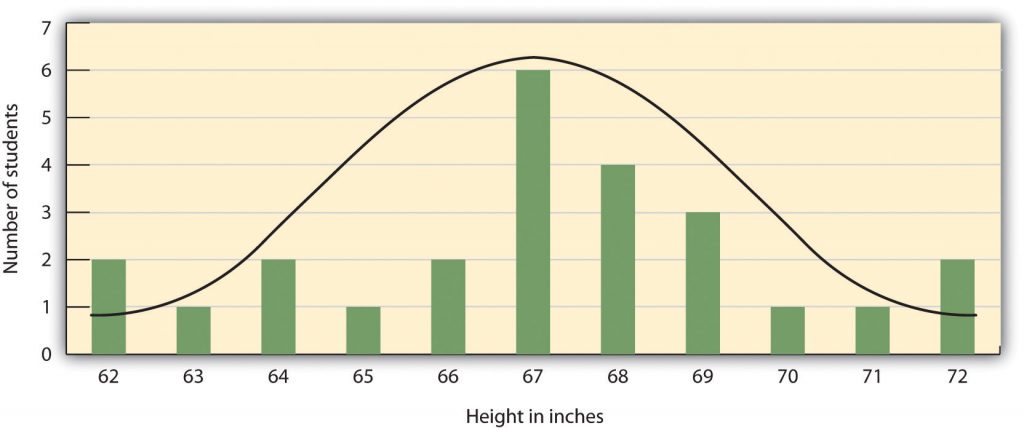

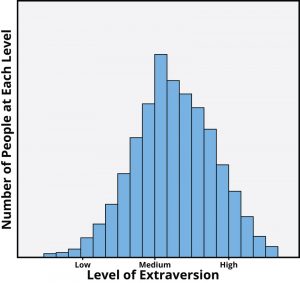

Continuous Distributions: A distribution in which most scores fall somewhere in the middle, with smaller numbers showing more extreme levels.

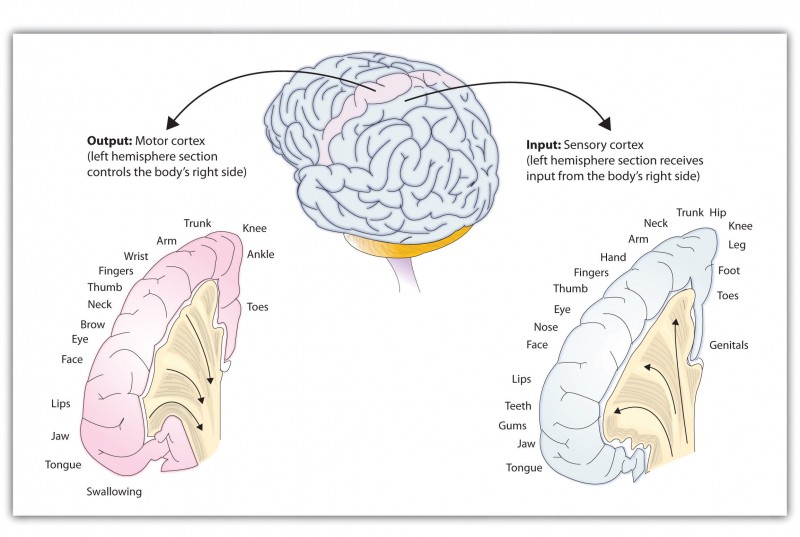

Contralateral Control: How the brain is wired such that in most cases the left hemisphere receives sensations from and controls the right side of the body, and vice versa.

Control: The belief in one’s own ability to control or influence events.

Controlled Behavior: a conscious behavior that is self-censored.

Convergence: the inward turning of our eyes that is required to focus on objects that are less than about 50 feet away from us.

Convergent Thinking: thinking that is directed toward finding the correct answer to a given problem.

Cornea: a clear covering that protects the eye and begins to focus the incoming light.

Corpus Callosum: The region that normally connects the two halves of the brain and supports communication between the hemispheres.

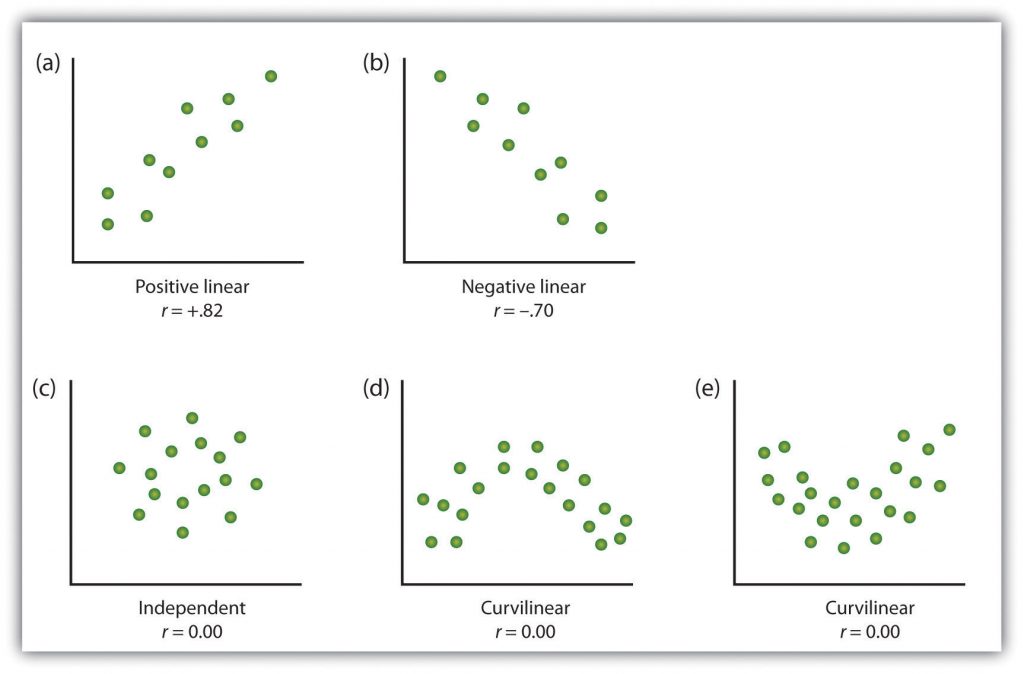

Correlational Research: research designed to discover relationships among variables and to allow the prediction of future events from present knowledge; involves the measurement of two or more relevant variables and an assessment of the relationships between or among those variables.

Cortisol: A primary stress hormone that increases sugars (glucose) in the bloodstream, enhances the brain’s use of glucose, and increases the availability of substances that repair tissues.

Cost–Benefit Analysis: The process that potential helpers engage in to determine the costs and benefits associated with helping. Or, when costs are compared with the benefits in a research project to determine the ethical standing of that research project.

Counterconditioning: A second incompatible response (relaxation) is conditioned to an already conditioned response (the fear response).

Counterfactual Thinking: the tendency to think about and experience events according to “what might have been”.

Couples Therapy: Treatment in which two people who are cohabitating, married, or dating meet together with the practitioner to discuss their concerns and issues about their relationship.

Critical Period: a time in which learning can easily occur.

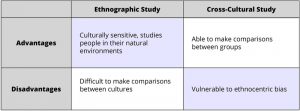

Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research that uses standard scales to compare cultural groups.

Cross-Cultural Studies: Research that uses standard forms of measurement to compare people from different cultures and identify their differences.

Cross-Sectional Research Design: Research designs in which age comparisons are made between samples of different people at different ages at one time.

Crystallized Intelligence: General knowledge about the world, as reflected in semantic knowledge, vocabulary, and language.

Crystallized Intelligence: the accumulated knowledge of the world we have acquired throughout our lives.

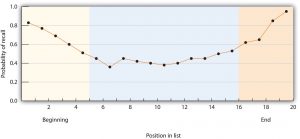

Cue Overload Principle: the principle stating that the more memories that are associated to a particular retrieval cue, the less effective the cue will be in prompting retrieval of any one memory.

Cues: a stimulus that has a particular significance to the perceiver (e.g., a sight or a sound that has special relevance to the person who saw or heard it).

Cultural Differences: Refers to the differences across cultures.

Cultural Display Rules: Rules that are learned early in life that specify the management and modification of our emotional expressions according to social circumstances.

Cultural Intelligence: The ability to understand why members of other cultures act in the ways they do.

Cultural Psychology: Attempts to understand and appreciate culture from the point of view of the people within it.

Cultural Relativism: The principle of regarding and valuing the practices of a culture from the point of view of that culture.

Cultural Scripts: How a person is taught how to behave according to regional cultural norms; people can have multiple cultural scripts.

Cultural Similarities: Refers to the similarities across cultures.

Culture of Honor: A cultural background that emphasizes personal or family reputation and social status.

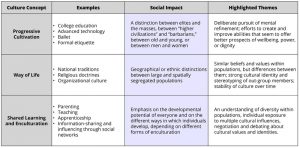

Culture: It is a collective understanding of the way the world works, shared by members of a group and passed down from one generation to the next. Represents the common set of social norms, including religious and family values and other moral beliefs, shared by the people who live in a geographical region.

Curvilinear Relationship: relationships that change in direction and thus are not described by a single straight line.

D

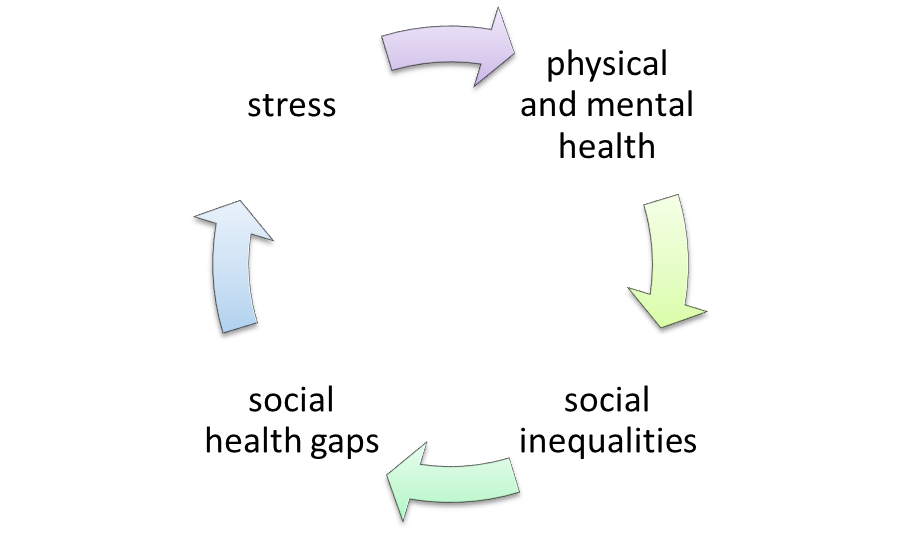

Daily Hassles: Everyday minor stressors that can raise blood pressure, alter stress hormones, and suppress the immune system function. Our everyday interactions with the environment that are essentially negative.

Data: any information that is collected through formal observation or measurement that is used within a research study.

Debriefing: refers to the process of informing research participants as soon as possible after the study about its purpose, disclosing any deception involved, and minimizing harm or misunderstandings that result from participating.

Decay: the fading of memories with the passage of time.

Deception: occurs whenever research participants are not completely and fully informed about the nature of the research project before participating in it.

Decibel: a unit of relative loudness.

Declaration of Helsinki: an ethics code that was created in 1964 by the World Medical Council.

Declarative Memory: conscious memories for facts and events.

Deep Structure of an Idea: how the idea is represented in the fundamental universal grammar that is common to all languages.

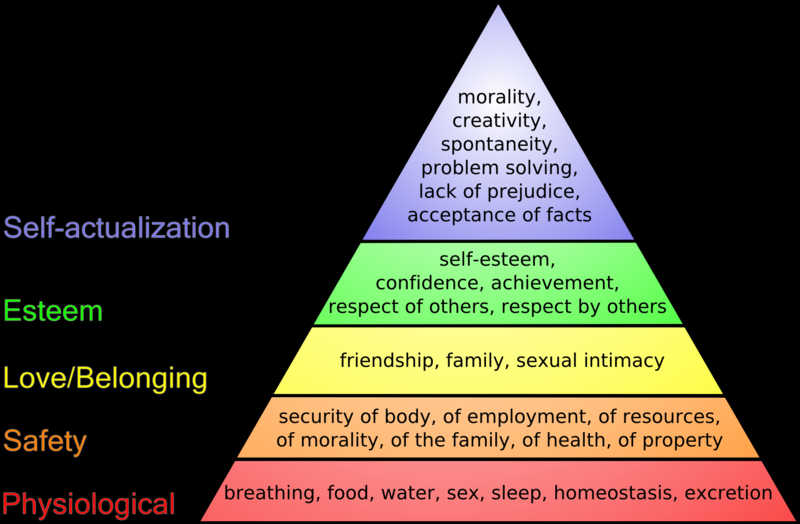

Deficiency Needs: The bottom four levels of Maslow’s pyramid, including physiological, safety, and social needs.

Deliberative Phase: A person must decide which of many potential goals to pursue at a given point in time.

Delusions: False beliefs not commonly shared by others within one’s culture and maintained even though they are obviously out of touch with reality.

Dementia: A progressive neurological disease that includes loss of cognitive abilities significant enough to interfere with everyday behaviours.

Dendrite: A branching treelike fibre that collects information from other cells and sends the information to the soma.

Dependence: a need to use a drug or other substance regularly.

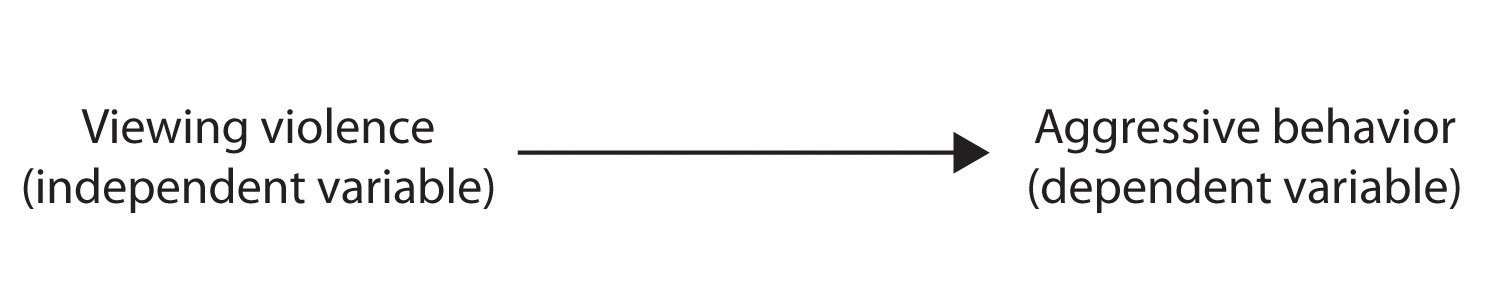

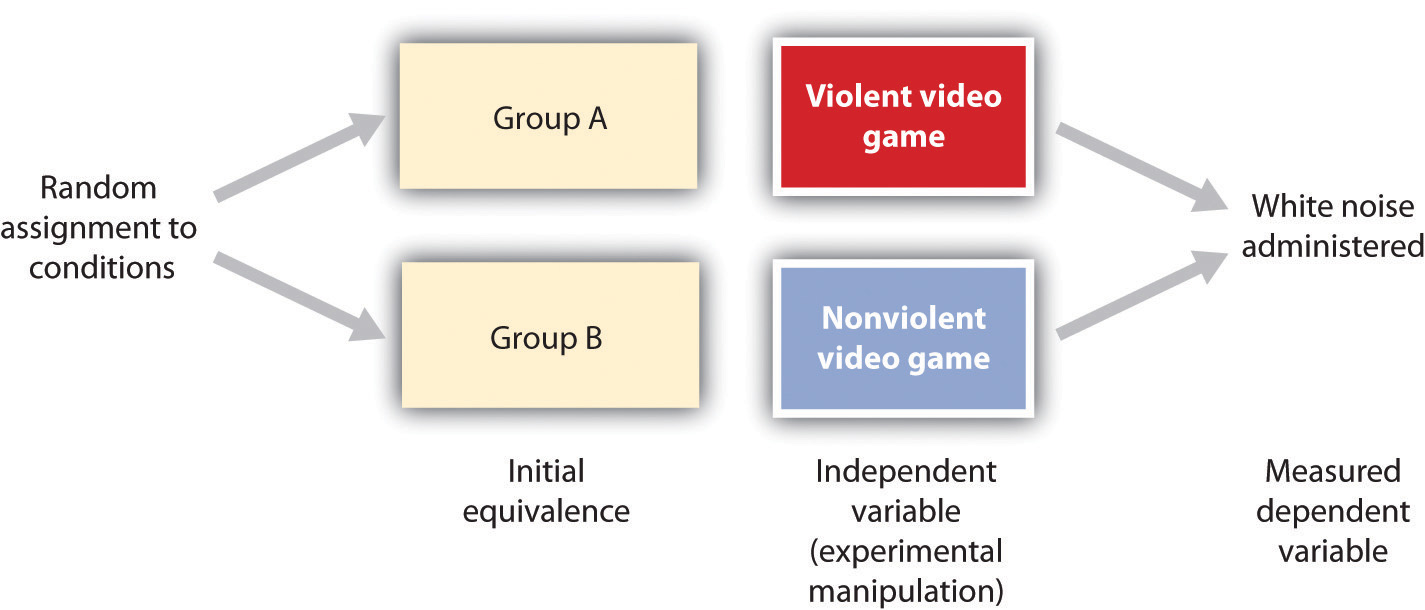

Dependent Variable: a measured variable that is expected to be influenced by the experimental manipulations.

Depressants: a class of drugs (psychoactive) that slow down the body’s physiological and mental processes. Also reduces the activity of the CNS.

Depression: a psychological disorder that affects millions of people worldwide and is known to be caused by biological, social, and cultural factors.

Depth Cues: messages from our bodies and the external environment that supply us with information about space and distance.

Depth Perception: the ability to perceive three-dimensional space and to accurately judge distance.

Derailment: The shifting from one subject to another, without following any one line of thought to conclusion.

Descriptive Norms: We act the way most people—or most people like us—act.

Descriptive Research: designed to provide a snapshot of the current state of affairs.

Descriptive Statistics: used to analyze descriptive research results by summarizing the distribution of scores.

Development: The physiological, behavioural, cognitive, and social changes that occur throughout human life, which are guided by both genetic predispositions (nature) and by environmental influences (nurture).

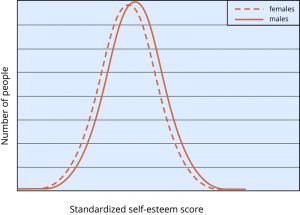

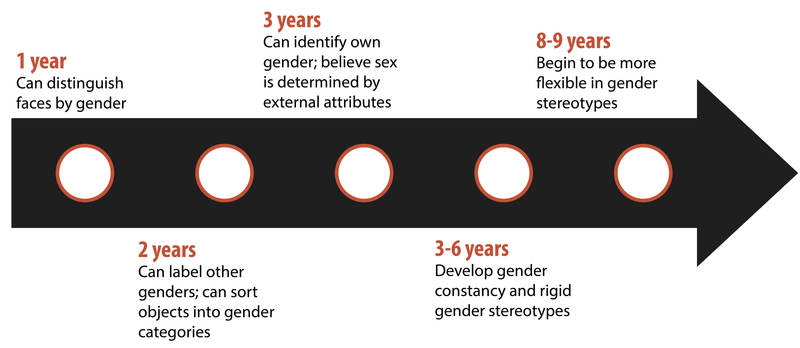

Developmental Intergroup Theory: Postulates that adults’ heavy focus on gender leads children to pay attention to gender as a key source of information about themselves and others, to seek out any possible gender differences, and to form rigid stereotypes based on gender that are subsequently difficult to change

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM): A document that provides a common language and standard criteria for the classification of mental disorders.

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT): Essentially a cognitive therapy, but it includes a particular emphasis on attempting to enlist the help of the patient in his or her own treatment.

Dichotic Listening: an experimental task in which two messages are presented to different ears.

Difference Threshold (or Just Noticeable Difference [JND]): the change in a stimulus that can just barely be detected by the organism.

Diffusion of Responsibility: A phenomenon in which bystanders are relived of personal responsibility and do not intervene because they know that someone else could help.

Direct Effects of Social Support: Having people we can trust and rely on helps us directly by allowing us to share favours when we need them.

Directional Goals: When we want a situation to turn out a particular way or our belief to be true.

Discrimination: When a person is biased against an individual, simply because of the individual’s membership in a social category.

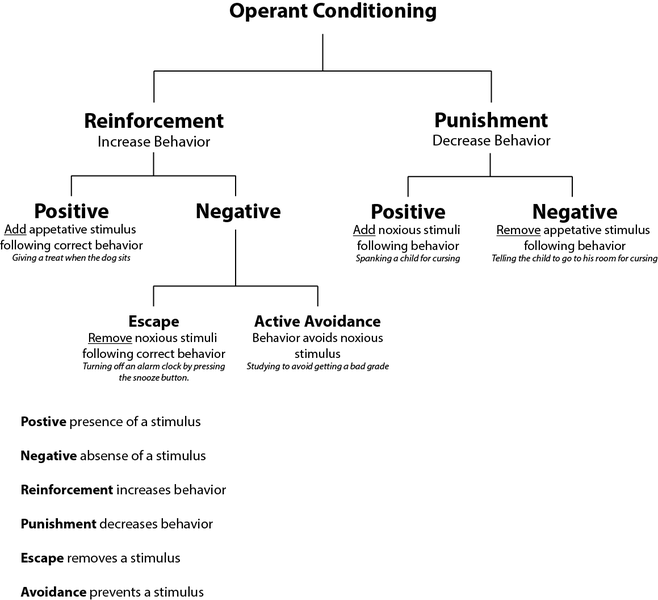

Discriminative Stimulus: in operant conditioning, a stimulus that signals whether the response will be reinforced. It is said to “set the occasion” for the operant response.

Disorganized Attachment Style: When a child has no consistent way of coping with the stress of the strange situation.

Dispersion: the extent to which the scores are all tightly clustered around the central tendency.

Dissociation: the heightened focus on one stimulus or thought such that many other things around you are ignored; a disconnect between one’s awareness of their environment and the one object the person is focusing on.

Dissociative Amnesia: A psychological disorder that involves extensive, but selective, memory loss, but in which there is no physiological explanation for the forgetting.

Dissociative Amnesia: loss of autobiographical memories from a period in the past in the absence of brain injury or disease.

Dissociative Disorder: A condition that involves disruptions or breakdowns of memory, awareness, and identity.

Dissociative Fugue: A psychological disorder in which an individual loses complete memory of his or her identity and may even assume a new one, often far from home.

Dissociative Identity Disorder: A psychological disorder in which two or more distinct and individual personalities exist in the same person, and there is an extreme memory disruption regarding personal information about the other personalities.

Distinctiveness: the principle that unusual events (in a context of similar events) will be recalled and recognized better than uniform (nondistinctive) events.

Distractor Task: a task that is designed to make a person think about something unrelated to an impending decision.

Distribution: the central tendency and spread of data for a particular variable

Divergent Thinking: the ability to generate many different ideas for or solutions to a single problem.

Divided Attention: A person’s ability to focus on two or more things at one time; the ability to flexibly allocate attentional resources between two or more concurrent tasks.

DNA Methylation: Covalent modifications of mammalian DNA occurring via the methylation of cytosine, typically in the context of the CpG dinucleotide.

DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs): Enzymes that establish and maintain DNA methylation using methyl-group donor compounds or cofactors. The main mammalian DNMTs are DNMT1, which maintains methylation state across DNA replication, and DNMT3a and DNMT3b, which perform de novo methylation.

Double-Blind Experiment: both the researcher and the participants are blind to condition.

Down Syndrome: a chromosomal disorder leading to mental retardation caused by the presence of all or part of an extra 21st chromosome.

Dream Analysis: The therapist listens while the client describes his or her dreams and then analyzes the symbolism of the dreams in an effort to probe the unconscious thoughts of the client and interpret their significance.

Dreams: The succession of images, thoughts, sounds, and emotions that passes through our minds while sleeping; Specific expressions of the unconscious that have a definite, purposeful structure indicating an underlying idea or intention.

Drive State: An affective experience (something you feel) that motivates organisms to fulfill goals that are generally beneficial to their survival and reproduction.

Dualism: a term used by Descartes that states that the mind is fundamentally different from the mechanical body; the idea that the mind, a nonmaterial entity, is separate from (although connected to) the physical body.

Durability Bias: The tendency for people to overestimate how long positive and negative events will affect them.

Dysthymia: A condition characterized by mild, but chronic, depressive symptoms that last for at least two years.

E

Early Adulthood: Roughly the ages between 25 and 45.

Echoic Memory: auditory sensory memory. Decays slower than iconic memory (4 seconds).

Eclectic Therapy: An approach to treatment in which the therapist uses whichever techniques seem most useful and relevant for a given patient.

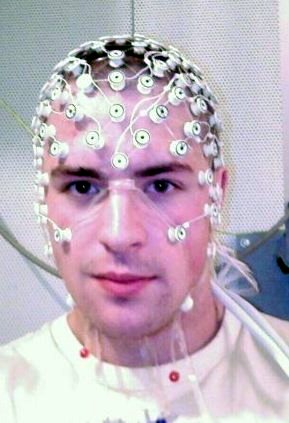

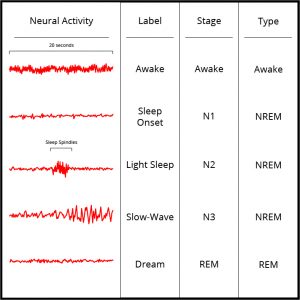

EEG (Electroencephalography): the recording of the brain’s electrical activity over a period of time by placing electrodes on the scalp.

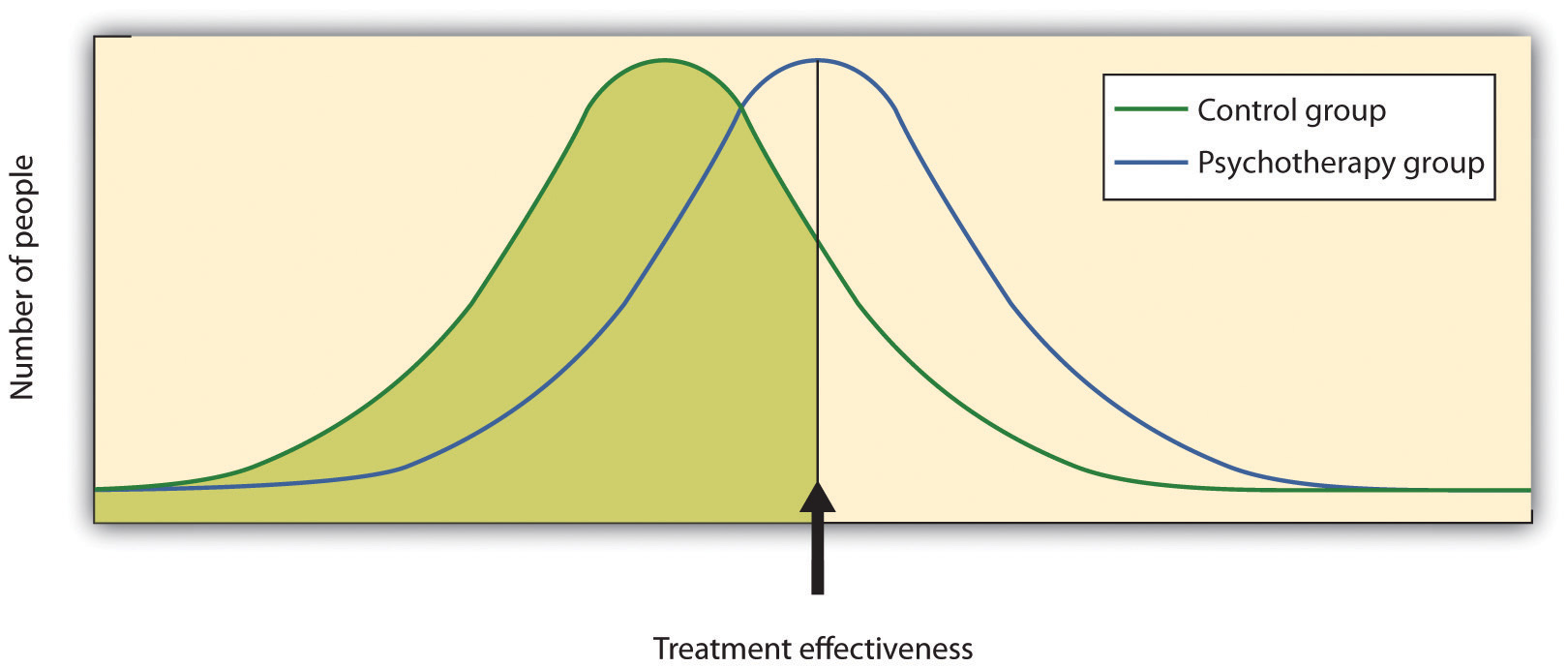

Effect Size: A measure of the effectiveness of treatment.

Ego-Depletion: The exhaustion of resource that occurs from resisting a temptation.

Egocentric: The inability to readily see and understand other people’s viewpoints.

Egoism: Being primarily concerned with one’s own cost–benefit outcomes.

Eidetic Imagery (or Photographic Memory): a type of memory that allows people the ability to report details of an image over long periods of time.

Elaborative Encoding: process new information in ways that make it more relevant or meaningful.

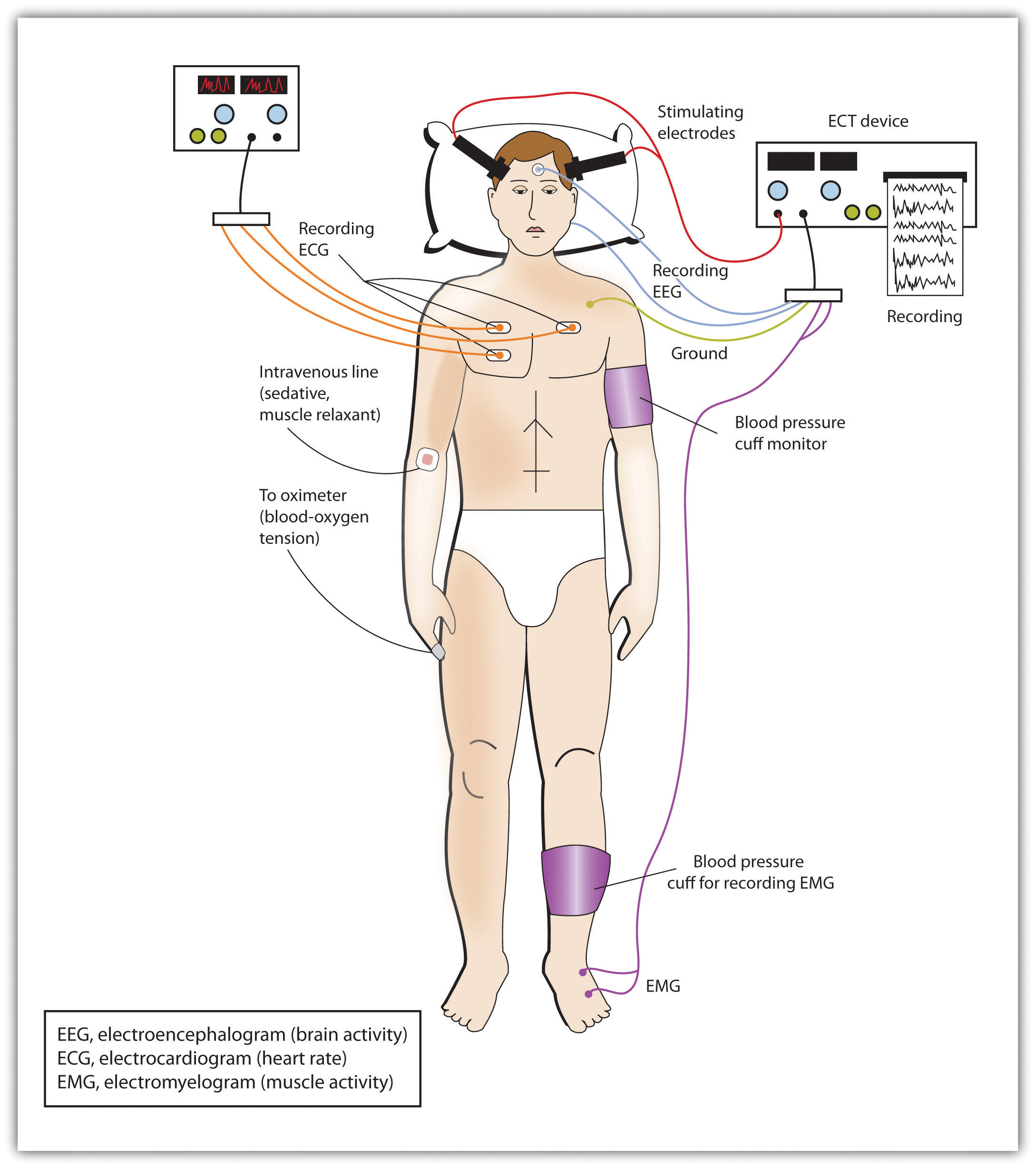

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT): A medical procedure designed to alleviate psychological disorder in which electric currents are passed through the brain, deliberately triggering a brief seizure.

Electroencephalography (EEG): A technique that records the electrical activity produced by the brain’s neurons through the use of electrodes that are placed around the research participant’s head.

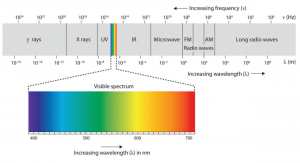

Electromagnetic Energy: pulses of energy waves that can carry information from place to place.

Embodied: becoming so closely in touch with the environment that the person’s body and the sensed environment becomes linked with our cognition, such that the world around us becomes part of our brain.

Embryo: A zygote that attaches to the wall of the uterus.

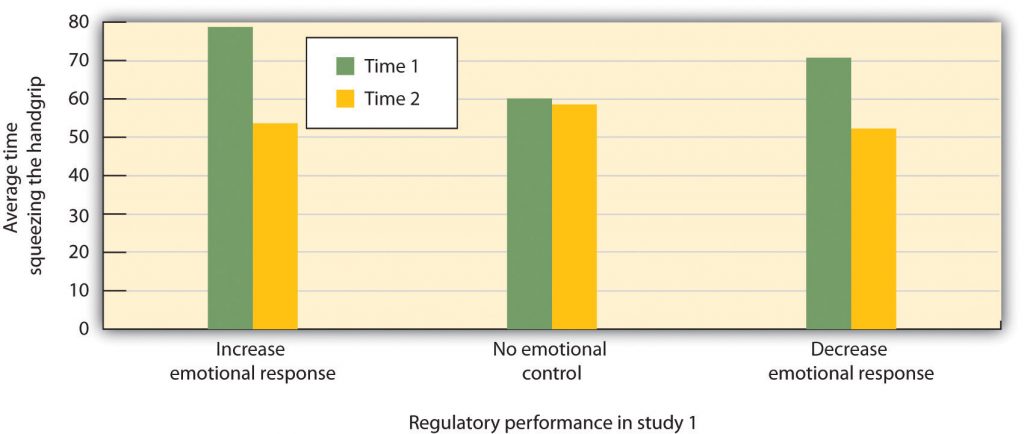

Emotion Regulation: The ability to control and productively use one’s emotions.

Emotion-Focused Coping: Regulates the emotions that come with stress.

Emotion: A mental and physiological feeling state that directs attention and guides behavior.

Emotional Intelligence (EI): the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions, and to effectively control one’s own emotions. EI includes four specific abilities: perceiving, using, understanding, and managing emotions.

Empathic Concern: When potential helpers become primarily interested in increasing the well-being of the victim, even if the helper must incur some costs that might otherwise be easily avoided.

Empathy–Altruism Model: Posits that the key for altruism is empathizing with the victim, that is, putting oneself in the shoes of the victim and imagining how the victim must feel.

Empirical Methods: refer to a set of methods used by scientists and include the processes of collecting and organizing data and drawing conclusions about those data.

Empirical: to be based on systematic collection and analysis of data.

Encoding Specificity Principle: the hypothesis that a retrieval cue will be effective to the extent that information encoded from the cue overlaps or matches information in the engram or memory trace.

Encoding: The initial experience of perceiving and learning events. It is the process by which we place the things that we experience into memory. The pact of putting information into memory.

Enculturation: Refers to the ways people learn about and shared cultural knowledge.

Endocrine System: The chemical regulator of the body that consists of glands that secrete hormones.

Engrams: a term indicating the change in the nervous system representing an event; also, memory trace.

Epigenetics: The study of heritable changes in gene expression or cellular phenotype caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence. Epigenetic marks include covalent DNA modifications and posttranslational histone modifications.

Epigenome: The genome-wide distribution of epigenetic marks.

Episodic Memory: Memory of autobiographical events that can be explicitly stated with a particular time and place. OR The firsthand experiences that we have had.

Error Management Theory (EMT): A theory of selection under conditions of uncertainty in which recurrent cost asymmetries of judgment or inference favor the evolution of adaptive cognitive biases that function to minimize the more costly errors.

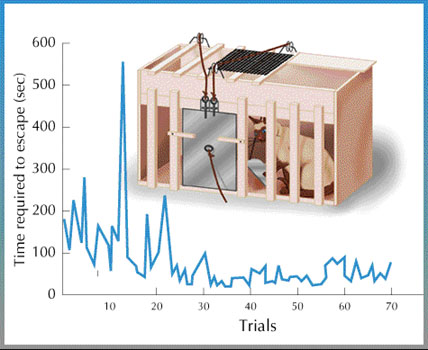

Escape Learning: A learned behaviour to terminate an unpleasant stimulus.

Estrogen: One of two female sex hormones secreted by the ovaries. Estrogen is involved in the development of female sexual features, including breast growth, the accumulation of body fat around the hips and thighs, and the growth spurt that occurs during puberty. Also involved in pregnancy and the regulation of the menstrual cycle.

Ethical Review Board (ERB): a committee of at least five members whose goal it is to determine the cost-benefit ratio of research conducted within in institution. Also known as an Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Ethics: a broad area within psychology that is concerned with what it means to be moral and how to act morally.

Ethnocentric Bias: The researcher who designs the study might be influenced by personal biases that could affect research outcomes, without even being aware of it.

Ethnographic Studies: Research in which the scientist spends time observing a culture and conducting interviews.

Eugenics: the proposal that one could improve the human species by encouraging or permitting reproduction of only those people with genetic characteristics judged desirable.

Euphoria: an intense feeling of pleasure, excitement or happiness.

Eureka Experience: when a creative product enters consciousness.

Eustress: Stress that is not necessarily debilitative and could be potentially facilitative to a person’s sense of well-being, capacity, or performance.

Evaluative Priming Task: An implicit test that measures how quickly the participant labels the valence of the attitude object when it appears immediately after a positive or negative image.

Event Time: scheduling is determined by the flow of the activity. Events begin and end when, by mutual consensus, participants “feel” the time is right.

Evolution: Certain traits and behaviors developing over time because they are advantageous to our survival.

Evolutionary Psychology: A branch of psychology that applies the Darwinian theory of natural selection to human and animal behaviour. Seeks to develop and understand ways of expanding the emotional connection between individuals and the natural world, thereby assisting individuals with developing sustainable lifestyles and remedying alienation from nature.

Exact (or Direct) Replication: scientific attempt to exactly copy the scientific methods used in an earlier study in an effort to determine whether the results are consistent. The same – or similar – results are an indication that the findings are accurate.

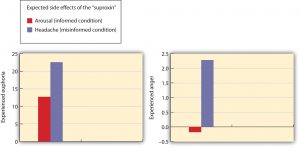

Excitation Transfer: The phenomenon that occurs when people who are already experiencing arousal from one event tend to also experience unrelated emotions more strongly.

Excitatory: Neurotransmitters that make the cell more likely to fire.

Exemplar: an example in memory that is labeled as being in a particular category.

Exempt Research: research projects in which the federal regulations do not apply given its nature (e.g., using data from public sources).

Existential Therapy: focuses on “man in the world” by emphasizing the choices to be made in the present and future and enabling a new freedom and responsibility to act.

Expectation Fulfillment Theory: posits that dreaming serves to discharge emotional arousals that haven’t been expressed during the day.

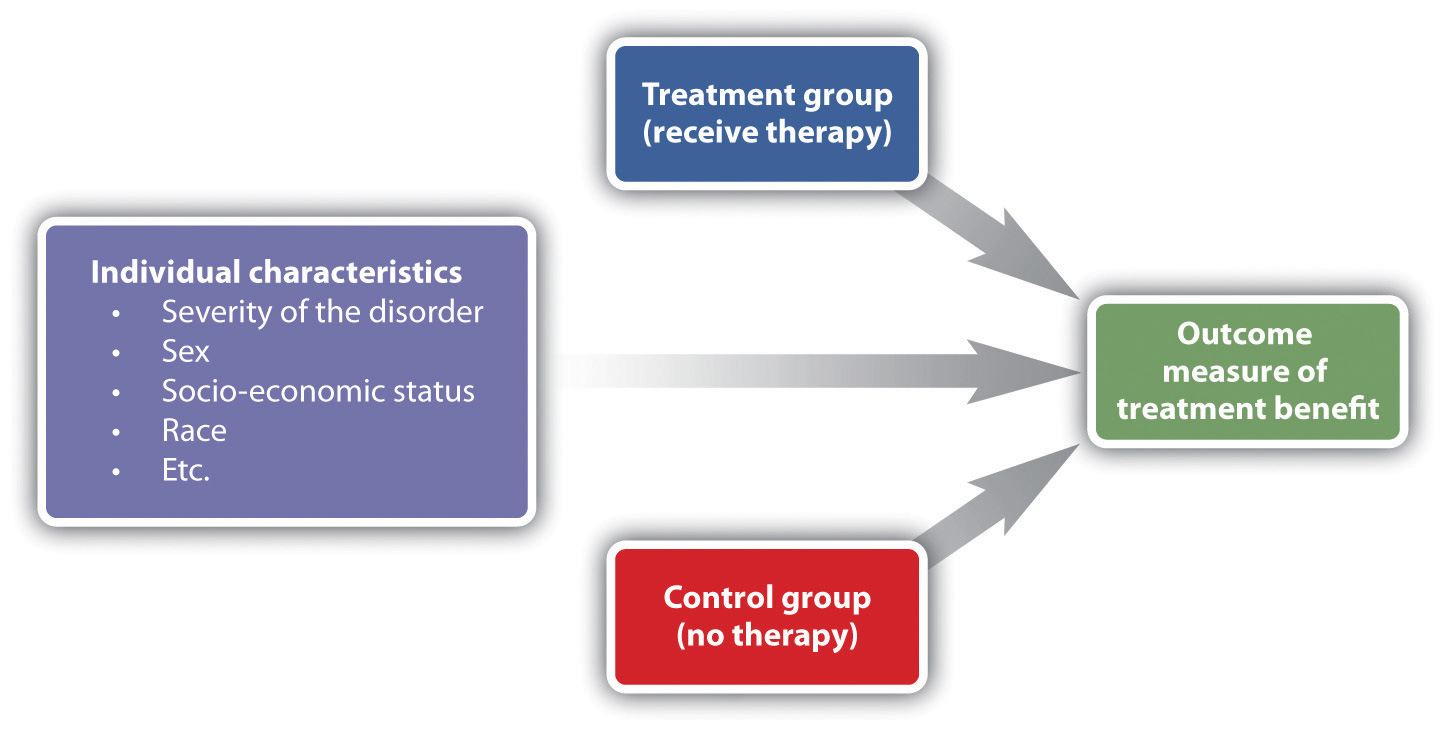

Experimental Research: research in which initial equivalence among research participants in more than one group is created, followed by a manipulation of a given experience for these groups and a measurement of the influence of the manipulation.

Experimenter Bias: a situation in which the experimenter subtly treats the research participants in the various experimental conditions differently, resulting in an invalid confirmation of the research hypothesis.

Explicit Attitude: An attitude that a person verbally or overtly expresses.

Explicit Memory: A type of memory that is conscious. Includes memories that are intentionally recollected, typically information that are factual such as previous experiences and concepts. Knowledge or experiences that can be consciously remembered. There are two types of explicit memory – episodic and semantic.

Exposure Therapy: A behavioural therapy based on the classical conditioning principle of extinction, in which people are confronted with a feared stimulus with the goal of decreasing their negative emotional responses to it.

External Locus of Control: When a person believes that his or her achievements and outcomes are determined by fate, luck, or other. If the person does not succeed, he or she believes it is due to external forces outside of the person’s control.

External Validity: the extent to which the results of a research design can be generalized beyond the specific way the original experiment was conducted.

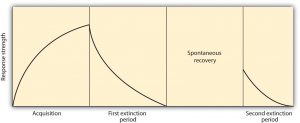

Extinction: decrease in the strength of a learned behavior that occurs when the conditioned stimulus is presented without the unconditioned stimulus (in classical conditioning) or when the behavior is no longer reinforced (in instrumental conditioning). The term describes both the procedure (the US or reinforcer is no longer presented) as well as the result of the procedure (the learned response declines). Behaviors that have been reduced in strength through extinction are said to be “extinguished.”

Extraversion: The tendency to be talkative, sociable, and to enjoy others; the tendency to have a dominant style.

Extravert: A person who is outer-directed.

Extrinsic Motivation: Motivation that comes from the benefits associated with achieving a goal.

F

Facets: More specific, lower-level units of personality.

Facial Feedback Hypothesis: Proposes that the movement of our facial muscles can trigger corresponding emotions.

Factor Analysis: A statistical method that helps to determine whether a small number of dimensions underlie a larger system.

Facts: objective statements that are determined to be accurate through empirical study.

False Memories: memory for an event that never actually occurred, implanted by experimental manipulation or other means.

False-Belief Test: an experimental procedure that assesses whether a perceiver recognizes that another person has a false belief—a belief that contradicts reality.

Falsified Data (or Faked Data): data that are fabricated, or made up, by researchers intentionally trying to pass off research results that are inaccurate. This is a serious ethical breach and can even be a criminal offense

Family Study: Starts with one person who has a trait of interest — for instance, a developmental disorder such as autism — and examines the individual’s family tree to determine the extent to which other members of the family also have the trait.

Family Therapy: Involves families meeting together with a therapist; in some cases, the meeting is precipitated by a particular problem with one family member.

Farsighted: an image is focused behind the retina, rather than on the retina. Occurs when the light rays bend incorrectly.

Fear Conditioning: a type of classical or Pavlovian conditioning in which the conditioned stimulus (CS) is associated with an aversive unconditioned stimulus (US), such as a foot shock. As a consequence of learning, the CS comes to evoke fear. The phenomenon is thought to be involved in the development of anxiety disorders in humans.

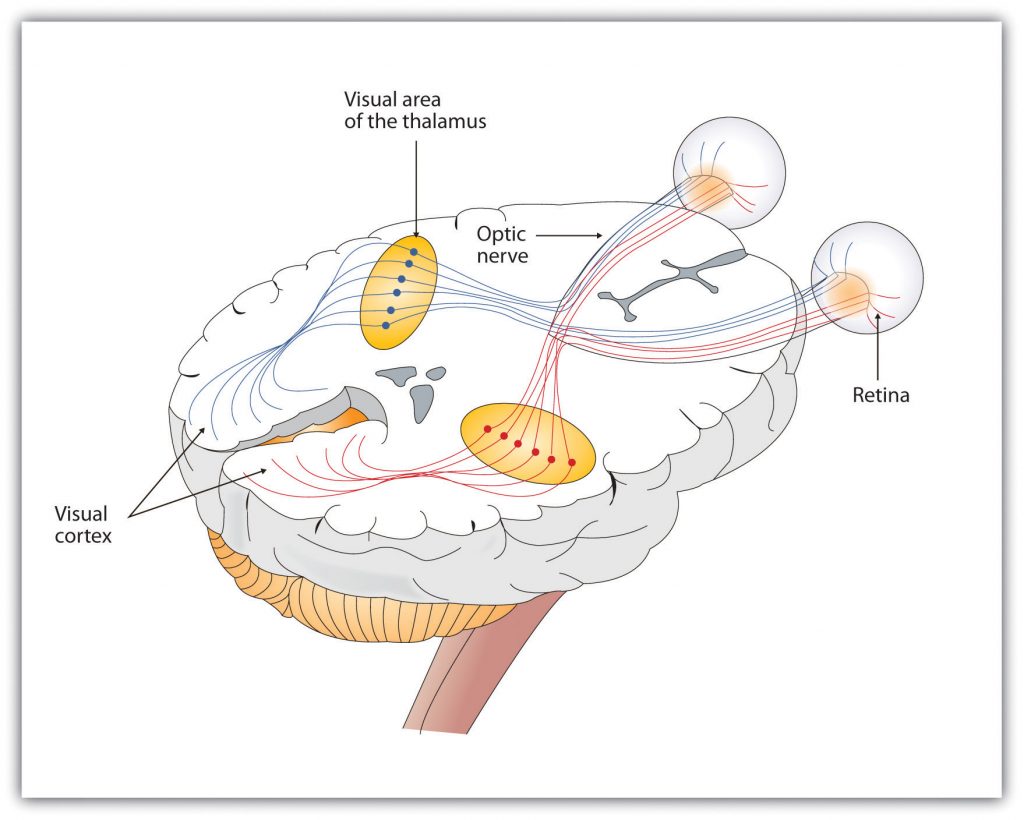

Feature Detector Neurons: Specialized neurons, located in the visual cortex, that respond to the strength, angles, shapes, edges, and movements of a visual stimulus.

Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects: a set of laws that were created from the Belmont Report that guides the conduct of research that is conducted, supported, or regulated by the federal government.

Feeling Function: Creative, warm, intimate.

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS): A condition caused by maternal alcohol drinking that can lead to numerous detrimental developmental effects.

Fight-or-Flight Response: A reflex that prepares the body to respond to danger in the environment; An emotional and behavioral reaction to stress that increases the readiness for action.

Fitness: refers to the extent to which having a given characteristic helps the individual organism survive and reproduce at a higher rate than do other members of the species who do not have the characteristic.

Flashbulb Memory: vivid and emotional personal memories of receiving the news of some momentous (and usually emotional and unusual) event that people believe they can remember very well.

Flexible Correction Model: the ability for people to correct or change their beliefs and evaluations if they believe these judgments have been biased (e.g., if someone realizes they only thought their day was great because it was sunny, they may revise their evaluation of the day to account for this “biasing” influence of the weather).

Flooding: A therapeutic technique in which a client is exposed to the source of his or her fear all at once.

Flourish: To grow and function successfully.

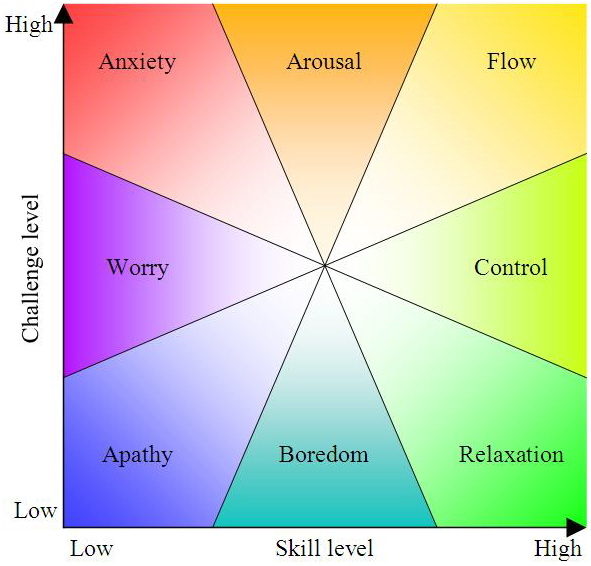

Flow: A state of optimal performance.

Fluid Intelligence: The ability to think and acquire information quickly and abstractly. The capacity to learn new ways of solving problems and performing activities.

Flynn Effect: the observation that scores on intelligence tests worldwide have increased substantially over the past decades.

Foils: any member of a lineup (whether live or photograph) other than the suspect.

Forgiveness: Creates a possibility for a relationship to recover from the damage caused by the offending party’s offense.

Formal Operational Stage: Marked by the ability to think in abstract terms and to use scientific and philosophical lines of thought.

Four-Branch Model: an ability model developed by Drs. Peter Salovey and John Mayer that includes four main components of EI, arranged in hierarchical order, beginning with basic psychological processes and advancing to integrative psychological processes. The branches are (1) perception of emotion, (2) use of emotion to facilitate thinking, (3) understanding emotion, and (4) management of emotion.

Fovea: the central point of the retina.

Framing: the bias to be systematically affected by the way in which information is presented, while holding the objective information constant.

Free Association: The therapist listens while the client talks about whatever comes to mind, without any censorship or filtering.

Frequency Theory of Hearing: proposes that whatever the pitch of a sound wave, nerve impulses of a corresponding frequency will be sent to the auditory nerve.

Frequency: the wavelength of the sound wave. Measured in terms of the number of waves that arrive per second.

Frontal Lobe: A portion of the brain located behind the forehead, also known as the motor cortex, that is involved in motor skills, higher level cognition (thinking, planning, memory, and judgment), and expressive language.

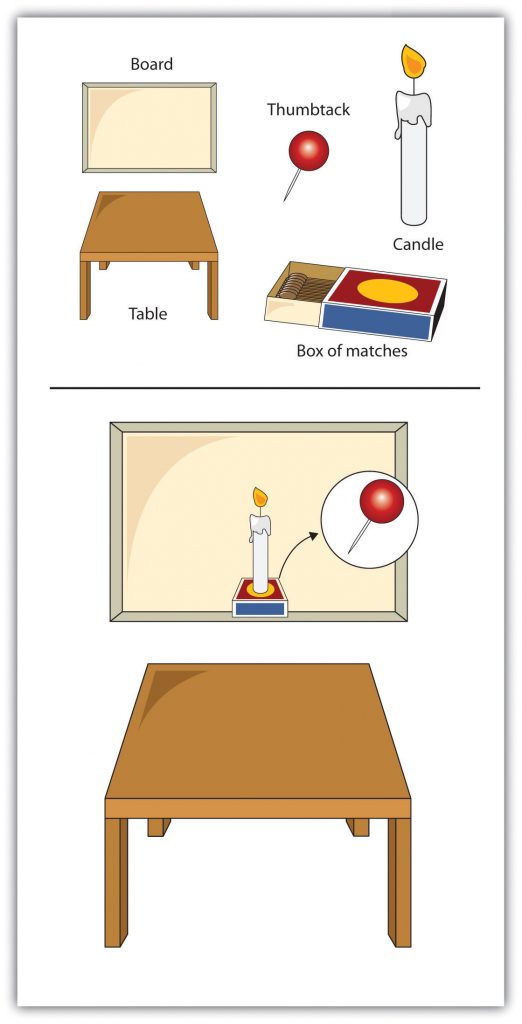

Functional Fixedness: occurs when people’s schemas prevent them from using an object in new and non-traditional ways.

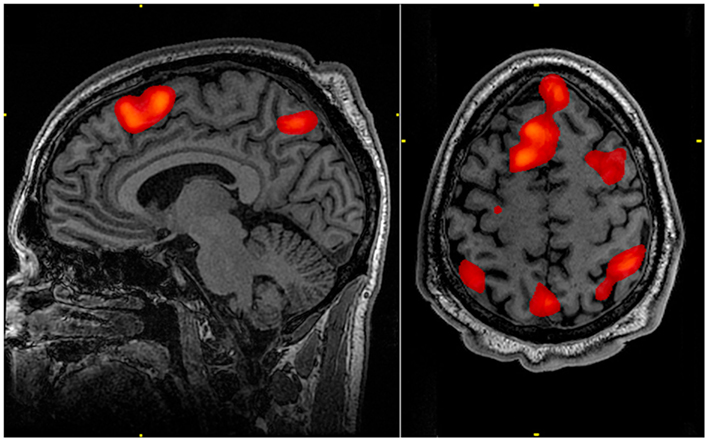

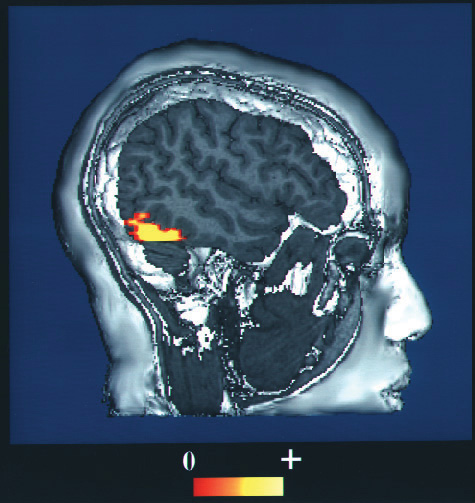

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI): A type of brain scan that uses a magnetic field to create images of brain activity in each brain area. Detects the amount of blood flow in each brain region and is an indicator of neural activity.

Functionalism (or School of Functionalism): School of psychology aimed at understanding why animals and humans have developed the particular psychological aspects that they currently possess

Fundamental Attribution Error: The consistent way we attribute people’s actions to personality traits while overlooking situational influences.

G

Gamification: A growing approach to behaviour modification today that involves applying game incentives such as prompts, competition, badges, and rewards to ordinary activities.

Gate Control Theory of Pain: proposes that pain is determined by the operation of two types of nerve fibres in the spinal cord.

Gender Constancy: By the third birthday, children can consistently identify their own gender and learn that gender is constant and can’t change simply by changing external attributes.

Gender Discrimination: Differential treatment on the basis of gender.

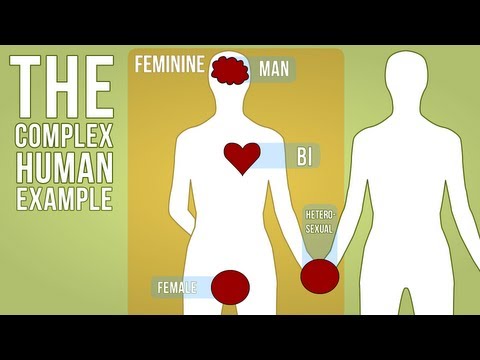

Gender Identity: Refers to a person’s psychological sense of being male or female.

Gender Roles: The behaviors, attitudes, and personality traits that are designated as either masculine or feminine in a given culture.

Gender Schema Theory: Argues that children are active learners who essentially socialize themselves.

Gender Stereotypes: The beliefs and expectations people hold about the typical characteristics, preferences, and behaviors of men and women.

Gender: Refers to the cultural, social, and psychological meanings that are associated with masculinity and femininity.

Gene Selection Theory: The modern theory of evolution by selection by which differential gene replication is the defining process of evolutionary change.

Gene: A specific deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequence that codes for a specific polypeptide or protein or an observable inherited trait. This basic biological unit transmits characteristics from one generation to the next.

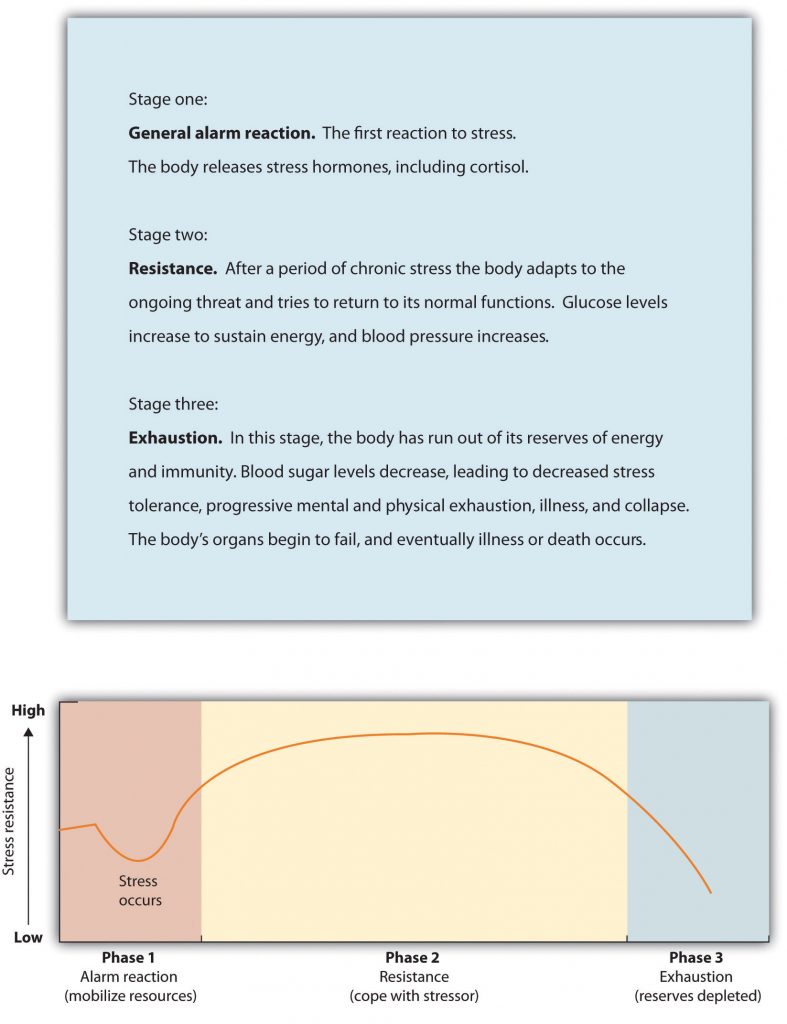

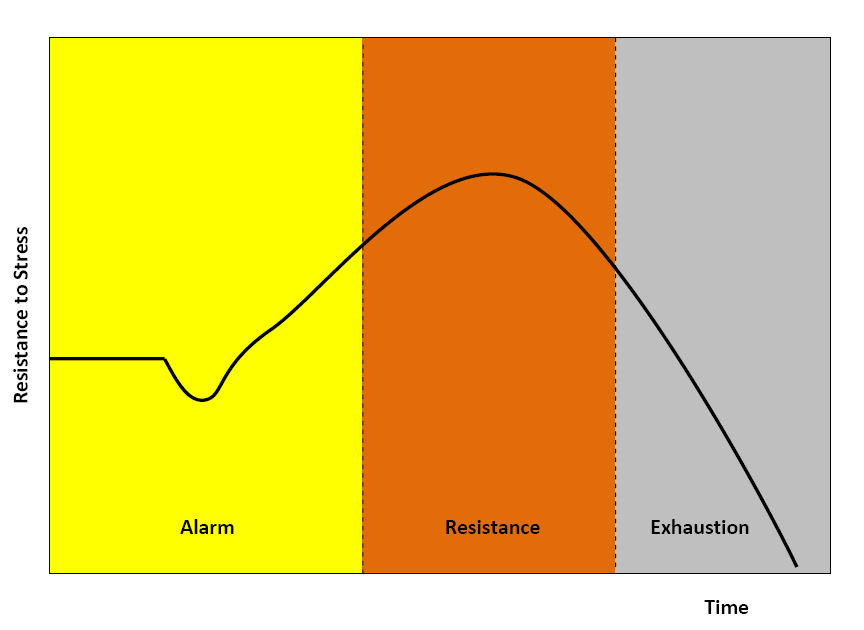

General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) Model: Describes three distinct phases of physiological change that occur in response to long-term stress: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion.

General Intelligence Factor (g): a construct that the different abilities and skills measured on intelligence tests have in common.

Generalization: the extent to which relationships among conceptual variables can be demonstrated in a wide variety of people and a wide variety of manipulated or measured variables.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): A psychological disorder diagnosed in situations in which a person has been excessively worrying about money, health, work, family life, or relationships.

Generativity: speakers of a language can compose sentences to represent new ideas that they have never before been exposed to.

Genotype: The DNA content of a cell’s nucleus, whether a trait is externally observable or not.

Gestalt Therapy: Focuses on the skills and techniques that permit an individual to be more aware of his or her feelings.

Gestalt: a meaningfully organized whole; a whole is more than the sum of its parts.

Gland: A gland in the endocrine system that is made up of a groups of cells that function to secrete hormones.

Glial Cells: (i.e., glia) Cells that surround and link to the neurons, protecting them, providing them with nutrients, and absorbing unused neurotransmitters.

Glutamate: a neurotransmitter and a form of the amino acid glutamic acid, is perhaps the most important neurotransmitter in memory.

Goal-Directed Behavior: instrumental behavior that is influenced by the animal’s knowledge of the association between the behavior and its consequence and the current value of the consequence. Sensitive to the reinforcer devaluation effect.

Goal: The cognitive representation of a desired state or mental idea of how we would like things to turn out.

Gratitude: A feeling of appreciation or thankfulness in response to receiving a benefit.

Group Therapy: Psychotherapy in which clients receive psychological treatment together with others.

Growth Need: the fifth level of Maslow’s pyramid that allows people to reach his or her fullest potential.

H

Habit: instrumental behavior that occurs automatically in the presence of a stimulus and is no longer influenced by the animal’s knowledge of the value of the reinforcer. Insensitive to the reinforcer devaluation effect.

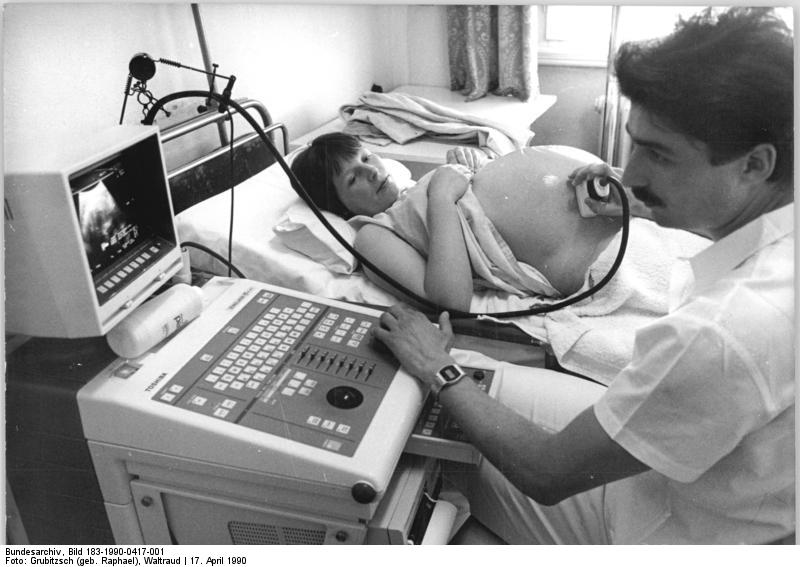

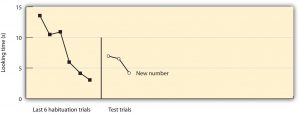

Habituation Procedure: When a baby is placed in a high chair and presented with visual stimuli while a video camera records the infant’s eye and face movements.

Habituation: The decreased responsiveness toward a stimulus after it has been presented numerous times in succession.

Hallucinations: Imaginary sensations that occur in the absence of a real stimulus or which are gross distortions of a real stimulus.

Hallucinogens: psychoactive drugs/substances that, when ingested, alter a person’s sensations and perceptions, often by creating hallucinations that are not real or distorting their perceptions of time.

Hardiness Theoretical Model: Refers to the resilient stress response patterns in individuals and groups.

Health Behaviors: Behaviors that can improve or harm health.

Helpfulness: People high in helpfulness believe they can be effective with the help they give they are more likely to be helpful in the future.

Helping: Prosocial behaviour that involves providing assistance to another person or group who is in need of help.

Heritability Coefficient: An easily misinterpreted statistical construct that purports to measure the role of genetics in the explanation of differences among individuals. The heritability coefficient varies from 0 to 1 and is meant to provide a single measure of genetics’ influence of a trait.

Heritability of the Characteristic: refers to the proportion of the observed differences of characteristics among people that is due to genetics.

Heritability: (i.e., genetic influence) Is indicated when the correlation coefficient for identical twins exceeds that for fraternal twins, indicating that shared DNA is an important determinant of personality.

Heroin: a strong addictive drug derived from opium; twice as addictive than morphine.

Hertz: vibrations per second.

Heuristics: Cognitive (or thinking) strategies that simplify decision making by reducing complex problem-solving to simpler, rule-based decisions. These information processing strategies are useful in many cases but may lead to errors when misapplied. Two frequently applied heuristics include the representativeness heuristic and the availability heuristic.

HEXACO Model: Posits that one important class of individual differences was omitted from the Five-Factor Model: Honesty-Humility.

High-Stakes Testing: Situations in which test scores are used to make important decisions about individuals.

Highlight: Prioritizing and putting greater effort towards goals.

Hindsight Bias: refers to the tendency to think that we could have predicted something that has already occurred that we probably would not have been able to predict.

Hippocampus: Located within the limbic system and consists of two “horns” that curve back from the amygdala. Important for the storage of information in long-term memory.

Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs) and Histone Deacetylases (HDACs): HATs are enzymes that transfer acetyl groups to specific positions on histone tails, promoting an “open” chromatin state and transcriptional activation. HDACs remove these acetyl groups, resulting in a “closed” chromatin state and transcriptional repression.

Histone Modifications: Posttranslational modifications of the N-terminal “tails” of histone proteins that serve as a major mode of epigenetic regulation. These modifications include acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, sumoylation, ubiquitination, and ADP-ribosylation.

Holist: Believing the whole is more than the sum of the parts.

Homeostasis: The natural balance in the body’s system. The tendency of an organism to maintain this stability across all the different physiological systems in the body.

Honeymoon Effect: The tendency for newlyweds to produce unrealistically positive ratings.

Hormone: A chemical that moves throughout the body to help regulate emotions and behaviours.

Host Personality: The personality in control of the body most of the time.

Hostile Sexism: Refers to the negative attitudes of women as inferior and incompetent relative to men.

Hostility: A pattern of arousal that involves becoming easily upset, angry, and having a negative personality style.

Hot Cognition: The mental processes that are influenced by desires and feelings.

HPA Axis: A physiological response to stress involving interactions among the (H) hypothalamus, the (P) pituitary, and the (A) adrenal glands.

Hue: the shade of a color.

Human Factors: the field of psychology that uses psychological knowledge, including the principles of sensation and perception, to improve the development of technology.

Human Intelligence: the ability to think, to learn from experience, to solve problems, and to adapt to new situations.

Humanistic Psychology: holds a hopeful, constructive view of human beings and of their substantial capacity to be self-determining.

Humanistic Therapy: A psychological treatment that emphasizes the person’s capacity for self-realization and fulfillment.

Humility: A clear and accurate sense of one’s abilities and achievements; the ability to acknowledge one’s mistakes, imperfections, gaps in knowledge, and limitations.

Hypnosis: the state of consciousness whereby a person is highly responsive to the suggestions of another; this state usually involves a dissociation with one’s environment and an intense focus on a single stimulus, which is usually accompanied by a sense of relaxation. OR a trancelike state of consciousness, usually induced by a procedure known as hypnotic induction, which consists of heightened suggestibility, deep relaxation, and intense focus

Hypnotherapy: The use of hypnotic techniques such as relaxation and suggestion to help engineer desirable change such as lower pain or quitting smoking.

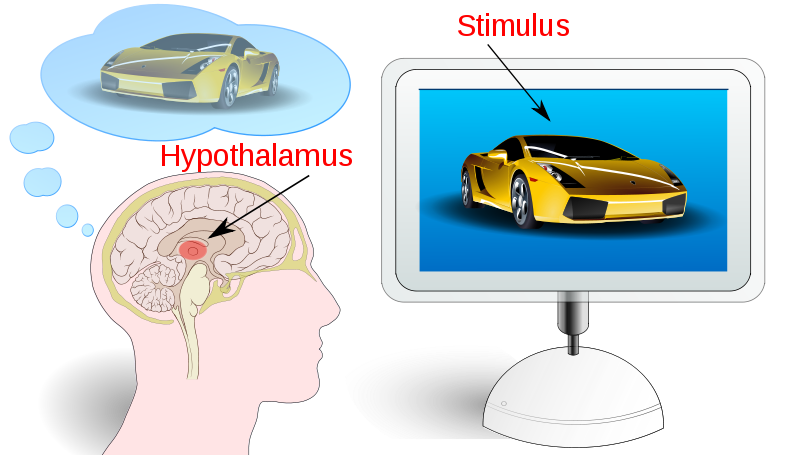

Hypothalamus: A brain region that is located in the lower, central part of the brain that is responsible for synthesizing and secreting hormones and plays an important role in eating behavior.

Hypothalamus: Part of the limbic system, located just under the thalamus. A brain structure that contains a number of small areas that perform a variety of functions, including the regulation of hunger and sexual behaviour, as well as linking the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland. Helps regulate body temperature, hunger, thirst, and sex, and responds to the satisfaction of these needs by creating feelings of pleasure.

Hypothesis: A proposed explanation for phenomenon that researchers test through research.

I

Iconic Memory: visual sensory memory. Decays rapidly (250 milliseconds).

Identical Elements Theory of Transfer: The more similar the situations are, the greater the amount of information that will transfer.

Identical Twins: Two individual organisms that originated from the same zygote and therefore are genetically identical or very similar. The epigenetic profiling of identical twins discordant for disease is a unique experimental design as it eliminates the DNA sequence-, age-, and sex-differences from consideration.

Identifiability: Identification or placement of a situation is a first response of the nervous system, which can recognize it.

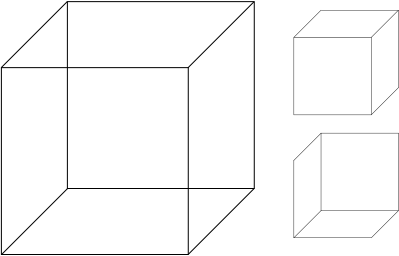

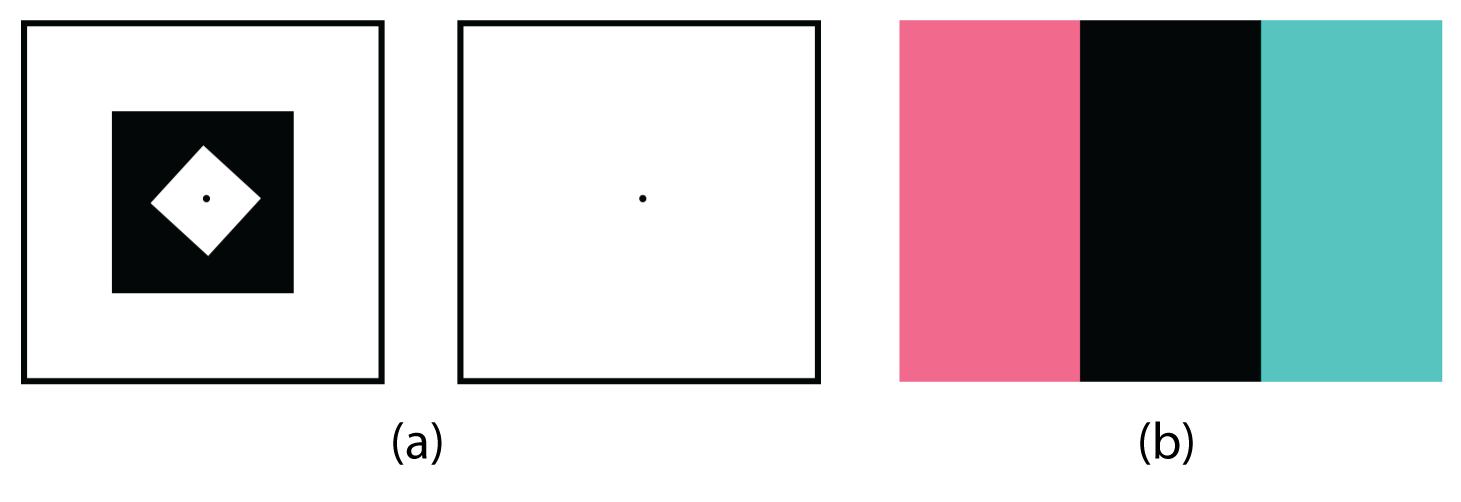

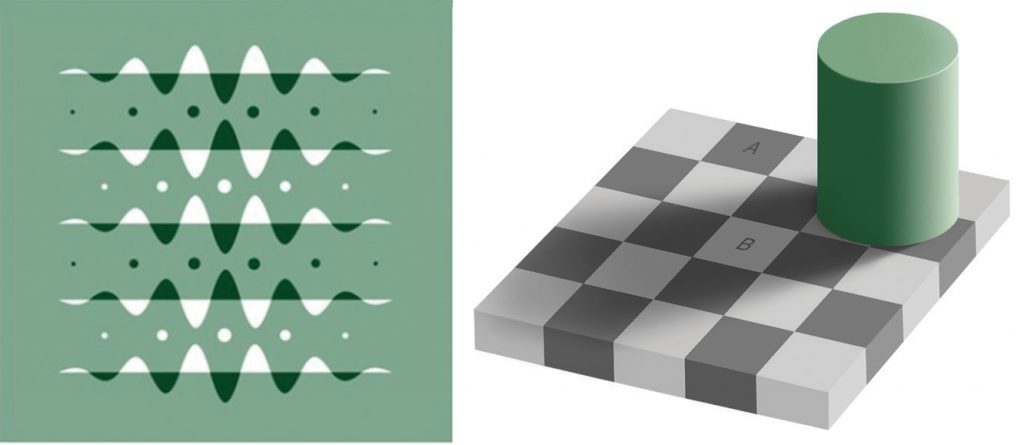

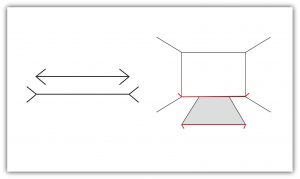

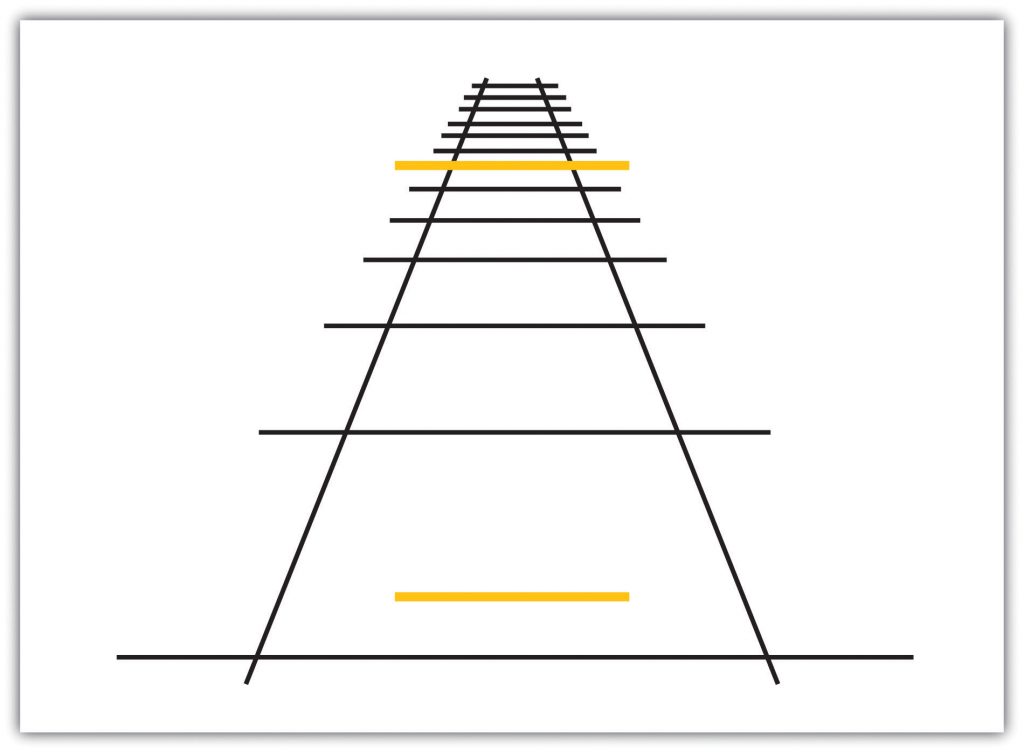

Illusions: occurs when the perceptual processes that normally help us correctly perceive the world around us are fooled by a particular situation so that we see something that does not exist or that is incorrect.

Imaginary Audience: Refers to when teenagers are so highly self-conscious that they feel that everyone is constantly watching them.

Impact Bias: The tendency for a person to overestimate the intensity of their future feelings.

Implemental Phase: Planning specific actions related to the goal and involves having a mindset that is conducive to the effective implementation of a goal.

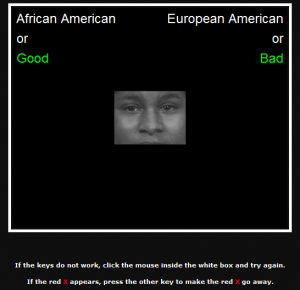

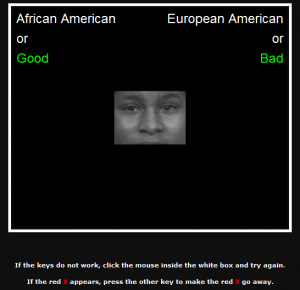

Implicit Association Test (IAT): A measure that assesses how quickly the participant pairs a concept with an attribute. A computer reaction time test measures a person’s automatic associations with concepts. For instance, the IAT could be used to measure how quickly a person makes positive or negative evaluations of members of various ethnic groups.

Implicit Attitude: An attitude that a person does not verbally or overtly express.

Implicit Learning: occurs when we acquire information without intent that we cannot easily express.

Implicit Measures of Attitudes: Measures that infer the participant’s attitude rather than having the participant explicitly report it.

Implicit Memory: a type of long-term memory that does not require conscious thought to encode. It’s the type of memory one makes without intent. Or, a memory that is acquired and used unconsciously. Implicit memories can affect a person’s thoughts and behaviors. Also the influence of experience on behavior, even if the individual is not aware of those influences.

Implicit Motives: Goals in which a person is not consciously aware of and that cannot be assessed via self-report.

Inattentional Blindness: the failure to notice a fully visible object when attention is devoted to something else.

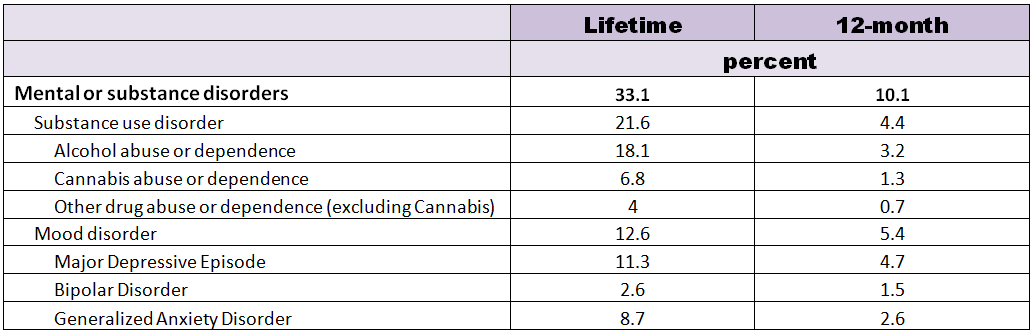

Incidence: refers to the estimated frequency or occurrence (prevalence) of a psychological disorder within a population.

Incidental Learning: any type of learning that happens without the intention to learn.

Independent Self: Views people as unique with a stable collection of personal traits that drive behavior; people tend to express their emotions to influence others.

Independent Variable: the causing variable that is created (manipulated) by the experimenter.

Individual Differences: the variations among people on physical or psychological dimensions.

Individualism: Emphasizes the uniqueness between people, personal freedom, and individual expression of opinions and decision-making. Norms in Western cultures that center on valuing the self and one’s independence from others.

Individuation: The process of integrating the conscious with the unconscious, synergizing the many components of the psyche.

Infancy: The developmental stage that begins at birth and continues to one year of age.

Information Processor: A system for taking information in one form and transforming it into another.

Informational Influence: People go along with the crowd because people are often a source of information.

Informed Consent: information given before a participant begins a research session, designed to explain the research procedures and inform that participant of his or her rights during the investigation.

Ingroup: group to which a person belongs.

Inhibitory: Neurotransmitters that make the cell less likely to fire.

Insight: An understanding by the patient of the unconscious causes of his or her symptoms.

Insomnia: persistent difficulty falling or staying asleep.

Instincts: Complex inborn patterns of behaviors that help ensure survival and reproduction.

Institutional Review Board (IRB): a committee of at least five members whose goal it is to determine the cost-benefit ratio of research conducted within in institution. Also known as an Ethical Review Board (ERB).

Instrumental Conditioning: process in which animals learn about the relationship between their behaviors and their consequences. Also known as operant conditioning.

Integrative Psychology: Psychology that combines the nature and actions of mind, body, and spirit.

Intentional Learning: any type of learning that happens when motivated by intention.

Intentional: an agent’s mental state of committing to perform an action that the agent believes will bring about a desired outcome.

Intentionality: the quality of an agent’s performing a behavior intentionally—that is, with skill and awareness and executing an intention (which is in turn based on a desire and relevant beliefs).

Interdependent Self. Views people as being different in each new social context and the social context as the primary drivers of behavior; people tend to control and suppress their emotions to adjust to others.

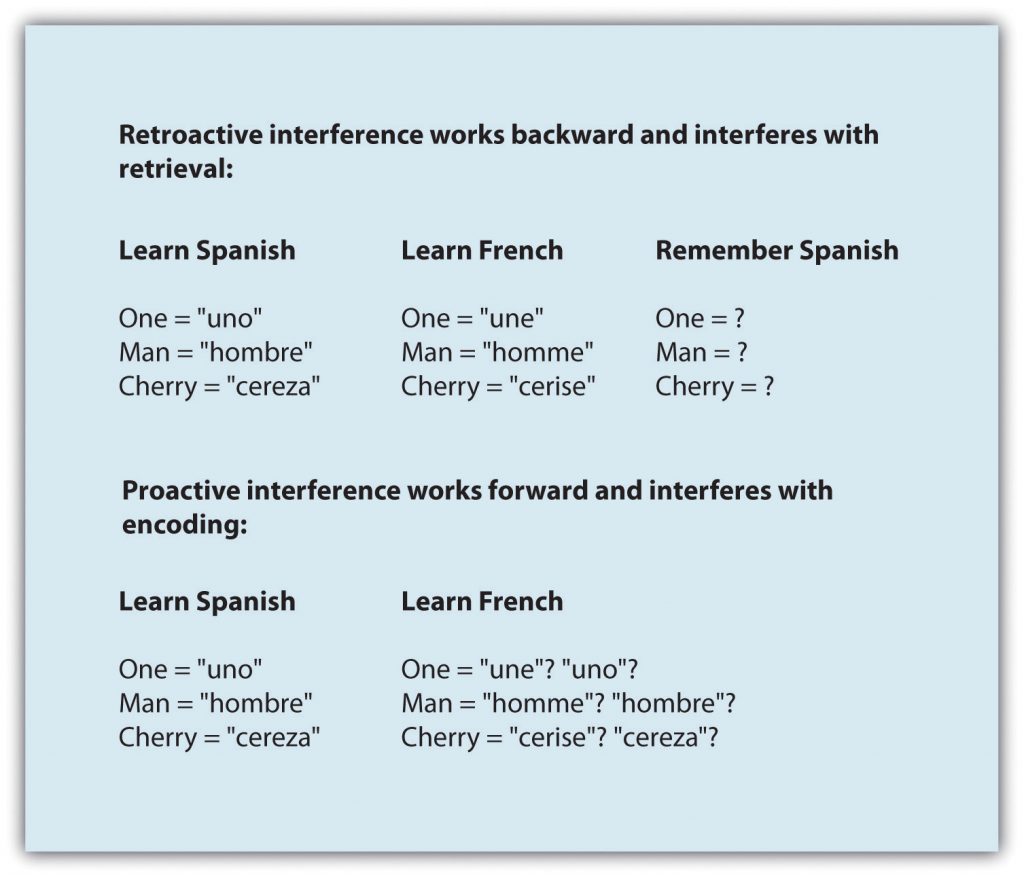

Interference: other memories get in the way of retrieving a desired memory

Internal Locus of Control: When a person believes that his or her achievements and outcomes are determined by his or her own decisions and efforts. If the person does not succeed, he or she believes it is due to his or her own lack of effort.

Internal Validity: the extent to which we can trust the conclusions that have been drawn about the causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

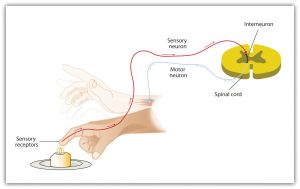

Interneuron: The most common type of neuron and is located primarily within the CNS. Responsible for communication among neurons. Interneurons allow the brain to combine the multiple sources of available information to create a coherent picture of the sensory information being conveyed.

Interpersonal Functions of Emotion: The role that emotions play between individuals within a group.

Interpersonal Intelligence: the capacity to understand the emotions, intentions, motivations, and desires of other people.

Interpretation: The therapist uses the patient’s expressed thoughts to try to understand the underlying unconscious problems.

Intersexual Selection: A process of sexual selection by which evolution (change) occurs as a consequences of the mate preferences of one sex exerting selection pressure on members of the opposite sex.

Intrapersonal Functions of Emotion: The role that emotions play within each of us individually.

Intrapersonal Intelligence: the capacity to understand oneself, including one’s emotions.

Intrasexual Competition: A process of sexual selection by which members of one sex compete with each other, and the victors gain preferential mating access to members of the opposite sex.

Intrinsic Motivation: A drive that powers human behaviour that results from the joy of the task itself. Motivation that comes from the benefits associated with the process of pursing a goal.

Introspection: A method used by structuralists to attempt to create a map of consciousness by asking research participants to describe exactly what they experience as they work on mental tasks. Asking research participants to describe exactly what they experience as they work on mental tasks.

Introvert: A person who is inner-directed.

Intuitive: Sees many possibilities in situations; goes with hunches; impatient with earthy details; impractical; sometimes not present.

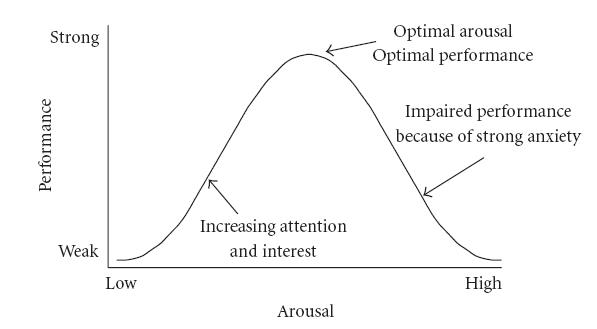

Inverted U Hypothesis: Asserts that, up to a point, stress can be growth inducing but that there is a turning or tipping point when stress just becomes too much and begins to become debilitative.

IQ: A measure of intelligence that is adjusted for age.

Iris: The coloured part of the eye that controls the size of the pupil by constricting or dilating in response to light intensity.

J

James-Lange Theory of Emotion: A theory proposed by William James and Carl Lange that states that arousal and emotion are not independent, but rather that emotion depends on the pattern of arousal.

Jet Lag: The state of being fatigued and/or having difficulty adjusting to a new time zone after traveling a long distance (across multiple time zones).

Job Analysis: determining what knowledge, skills, abilities, and personal characteristics (KSAPs) are required for a given job.

Joint Attention: two people attending to the same object and being aware that they both are attending to it.

Justice: an ethical principle from the Belmont Report that emphasizes distributing risks and benefits fairly across different groups within society.

K

Kin Selection: The favoritism shown for helping our blood relatives.

Knocked Out: The action that certain genes will be eliminated during the creation of DNA.

L

Lack of Executive Control: Difficulty comprehending information and using it to make decisions.

Language: a system of communication that uses symbols in a regular way to create meaning. Gives the ability communicate our intelligence to others by talking, reading, and writing.

Late Adulthood: The final life stage, beginning in the 60s.