Introduction

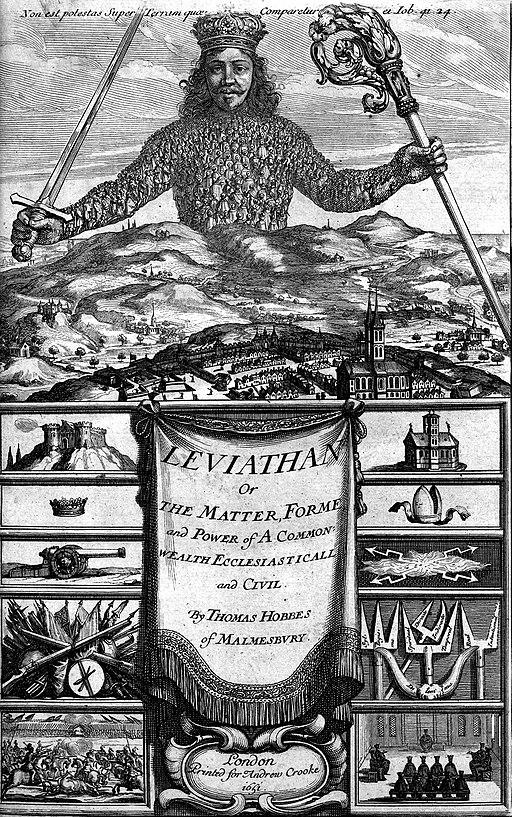

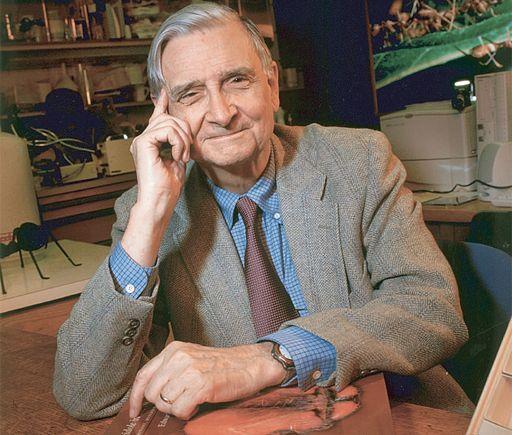

As the world’s leading ant expert, Edward Wilson could have led a tranquil and joyous academic life. But in his book Sociobiology from 1975, Wilson extended his work on evolutionary explanations of social behavior—which helped him a great deal in understanding the behavior of social animals like ants, bees, and horses—to human behavior. As Wilson later wrote, all of the book’s 575 pages were well received but for the last, brief chapter on human evolution (Wilson 2002, vi). In that chapter, Wilson suggests that evolution could explain moral behavior in humans: humans are moral, prosocial animals because being moral and prosocial had evolutionary advantages. Indeed, he urged that “scientists and humanists should consider together the possibility that the time has come for ethics to be removed temporarily from the hands of the philosophers and biologicized” (Wilson 2002, 562).

Wilson’s suggestion caused outrage far beyond the academic ivory tower. Many associated evolutionary theory with crude claims about the “survival of the fittest,” which some regimes used to justify wars and euthanasia, and they feared that approaching ethics from the evolutionary perspective would justify racism, sexism, and imperialism. In effect, Wilson’s academic life after the publication of the book was far from tranquil; his talks were controversial, shouted down by protesters, and at a conference in 1978, an opponent even expressed his dismay by emptying a can of water over him.

However, looking behind Wilson’s sensational rhetoric of “removing ethics from the hands of the philosophers” we find a more level-headed claim about methodology in ethics (Wilson 2002, 562). Wilson called for studying ethics just as we study other social, psychological, or biological phenomena. In other words, Wilson called for a so-called naturalistic approach to ethical questions (which will be explained in further detail below). Of course, we can ask many different questions about ethics and, as we will see, some are more suited to a naturalistic approach than others. But the debate about the legitimacy of evolutionary ethics has largely abated in favor of Wilson’s proposal. Many aspects of evolutionary ethics are thriving and have led to exciting research programs that have made tremendous progress since Wilson’s book. And Wilson, rest assured, came out of the controversy emboldened and unscathed. It seems that he did lead a joyous academic life after all.

This chapter first introduces naturalistic approaches to ethics more generally and distinguishes methodological ethical naturalism (the focus of this chapter), from metaphysical ethical naturalism. The second part then discusses evolutionary ethics as a specific variant of methodological ethical naturalism. After introducing the concepts of evolutionary theory that are relevant for evolutionary ethics, I will sketch the history of evolutionary ethics, which offers an interesting lesson about why it became a controversial topic, and then focus on four central questions about ethics that can be approached from within the framework of evolutionary ethics:

- What should we do?

- Why are we moral?

- Are there moral facts?

- Can we have justified moral beliefs and moral knowledge?

Two Approaches to Naturalism in Ethics: Methodological and Metaphysical

Wilson advocates methodological ethical naturalism, which is primarily a view about the best ways to study ethics. Naturalists in this sense argue that at least some ethical questions can be studied just as we try to answer questions in other fields of scientific inquiry. Ethics, in other words, is continuous with science.

A central commitment of methodological ethical naturalism is to widen the net of our sources for ethical inquiry. For example, we can use anthropological, psychological, biological, and literary sources to inform our theorizing about ethics. Such a multitude of sources contrasts with the more traditional way of doing moral philosophy by conceptual analysis. Conceptual analysis is a method often used by philosophers to investigate ethical questions. It involves reflection about when a concept, such as “goodness” or “freedom,” applies and how it relates to other concepts. Using conceptual analysis to understand what moral goodness is, for example, means analyzing the conditions in which the concept “moral goodness” applies. Conceptual analysis is guided by one’s understanding of and intuitions about the concept in question. Since much of the academic philosophy studied by North American and European philosophers still is, or has been, done by North Americans and Europeans (despite the fact that academic philosophy is being done in other parts of the world, too), many existing conceptual analyses of ethical terms are really conceptual analyses of Western concepts. However, psychologists and philosophers have argued that intuitions about (ethical) concepts vary quite significantly. If these claims are true, it would be a problem insofar as we want to learn what moral goodness is, rather than what the concept of moral goodness of Western academics is. Hence, the naturalist has a good case for taking into account more than just (predominantly Western) intuitions. Evolutionary thinking is one such source, and we will cover it in greater detail below.

In contrast to methodological naturalism, which is primarily a view about how to conduct ethical inquiry, metaphysical ethical naturalism is primarily a view of what exists. Both views are related but distinct, as an analogy with ghosts illustrates. It would be one thing to find out in scientifically respectable terms why people believe in ghosts, which would be methodological naturalism, but quite another to say what ghosts are in scientifically respectable terms, which would be the goal of the metaphysical naturalist.

Metaphysical naturalists say that there are no non-natural or supernatural entities in this world. On most accounts of drawing the line between “natural” and the rest, this excludes God or gods, ghosts, human spirits, or a soul that is not part of the physical body. Morality seems to fall on the non-natural or supernatural side of things to many philosophers. One reason is that moral facts seem quite unlike ordinary facts about, say, the weather or geology, due to their normative force. To illustrate, if I state an ordinary fact like “Mitt went to the grocery store” or “gold is denser than iron,” I describe a state of the world, but I do not seem committed to acting in one way or another. In contrast, if I say “it is morally wrong that Mitt stole the money,” I not only describe the world, but also seem to commit myself to act in a certain way. It sounds strange to say, for example, that “it is morally wrong that Mitt stole the money but we should do nothing about it.” Moral facts, it seems, have a certain prescriptivity built into them, and this is one reason it seems that moral facts cannot straightforwardly be reduced to natural facts. (To wit, moral facts, such as the fact that killing is wrong, not only describe the world like other facts, but they also give reasons for acting, or prescribe certain courses of action.)

As a solution, some metaphysical naturalists abandon moral facts altogether. Since there are no moral facts at all on this view, this is, of course, a straightforward way to live up to one’s naturalistic aspirations. Typically, however, when moral philosophers speak about moral naturalism, they have in mind a version of metaphysical ethical naturalism that is committed to two theses. First, moral facts exist. Second, moral facts can be described in purely natural terms. For example, consider the moral theory utilitarianism (see Chapter 5). A simple version of utilitarianism holds that the only thing of intrinsic value is happiness and that our only obligation is to maximize happiness. On this view, moral properties reduce to the property of being conducive to happiness, which is a psychological quality that fits quite well into the worldview provided by science. The major philosophical project of metaphysical naturalists is to explain how exactly moral facts relate to natural facts, which raises some fascinating issues. For present purposes, it is important to note that you can be a methodological naturalist without being committed either to one of the two forms of metaphysical naturalism or to metaphysical naturalism in general. That means you can embrace methodological naturalism but deny that there are only natural facts. From now on, we will focus on methodological naturalism, and in the next section, we will see how evolutionary ethics is a particular instance of methodological ethical naturalism.

Evolutionary Ethics as Methodological Approach to Naturalism in Ethics

Evolutionary Theory and Ethics

Evolutionary ethics takes into account the findings of human evolutionary psychology, a field of study that explores how evolutionary forces helped shape not only how humans function and what we look like (what evolutionary biologists call the human “phenotype”), but also how we behave, feel, and think. Evolutionary ethics is thus a way in which we can widen the net of sources that inform ethical inquiry.

Evolutionary psychology itself is based on the theory of evolution by natural selection applied to human beings, first described by Charles Darwin in 1871 in his book The Descent of Man. In this book, Darwin argued that we humans are the descendants of a “hairy quadruped, furnished with a tail and pointed ears, probably arboreal in its habits, and an inhabitant of the Old World” (Darwin 1871, 389).

Darwin’s theory describes natural selection as the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. Natural selection is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in heritable traits of a population of individuals over time. Natural selection works similarly to artificial selection. Take a dog breeder, for example, who selects only docile dogs to breed. Over multiple generations, the dogs he breeds will get more and more docile. The major difference between artificial selection and natural selection is that natural selection does not have a “selector.” Instead, environmental conditions cause some phenotypes (and consequently, their genotypes) to be able to survive and reproduce better compared to their competitors. Organisms that are better adapted to the environment, perhaps through random mutations of their genetic code, are said to have a greater fitness as they have a greater chance of passing on their genes. Thus, over time, fitness-enhancing changes in the genotype spread in the next generation. The theory of evolution by natural selection provides the starting point for evolutionary ethics, as we will see in the next section.

What Should We Do?

When Darwin published The Descent of Man, people immediately began to think about the relations between his theory of human evolution and ethics. One of the important early proponents of an ethical theory inspired by evolutionary theory was Herbert Spencer. Spencer, born in 1820 in England, argued that Darwin’s evolutionary theory would not only explain but also justify moral behavior. He became known as the foremost defender of the branch of evolutionary ethics that attempts to deal with answers to the question what we ought to do (more on this below), and he was a key figure in popularizing Darwin’s ideas in application to the study of ethics. A recollection by Frederick Pollock, who studied at Cambridge University in England during the height of Spencer’s popularity, nicely illustrates the enthusiasm with which many adopted the new way of thinking about ethics:

We seemed to ride triumphant on an ocean of new life and boundless possibilities. Natural Selection was to be the master-key of the universe; we expected it to solve all riddles and reconcile all contradictions. Among other things it was to give us a new system of ethics, combining the exactness of the utilitarian with the poetical ideals of the transcendentalist. We were not only to believe joyfully in the survival of the fittest, but to take an active and conscious part in making ourselves fitter. (Clifford 1879, 33)

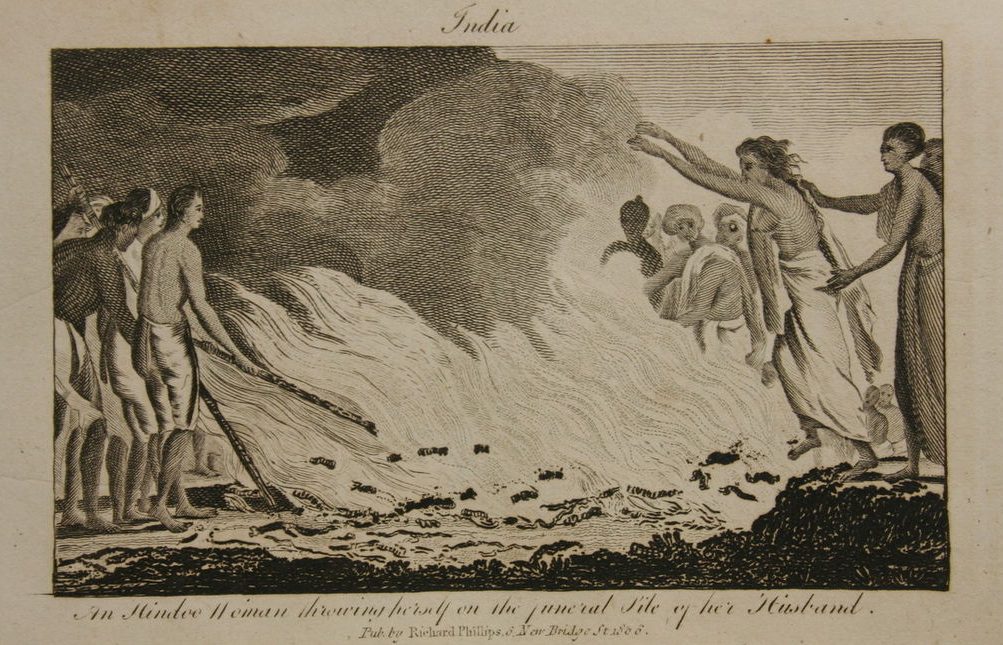

The research program inspired by Spencer provides an important lesson about the pitfalls of evolutionary ethics. (See the box on Social Darwinism for more details.) Spencer’s followers thought that evolutionary theory could show that certain moral principles or rules are justified. Recall one of the core premises in evolutionary theory about the role of individual differences in natural selection. Fit phenotypes survive and reproduce more or better than unfit phenotypes. For this reason, many have thought that finding out what is evolutionarily successful shows us what is morally good. Darwin’s theory has been, mistakenly, taken as a justification for the belief that it is right for the strong to crowd out the weak and that the only hope for human improvement lays in selective breeding.

Carrie Buck was a patient in the “Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-minded,” as it was called at the time. Upon a finding that she was “the probable potential parent of socially inadequate offspring, likewise afflicted, that she may be sexually sterilized without detriment to her general health, and that her welfare and that of society will be promoted by her sterilization,” the Court ruled that she could be sterilized without her consent (Buck v. Bell 274, U.S. 200, [1927]). In justifying the ruling, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes infamously remarked that “three generations of imbeciles are enough” (Doerr 2009).

The court’s ruling cites the common good, and the alleged inability of Carrie Buck to contribute to it, as a justification for the ruling. Implicitly, the court assumes that “unproductive” people, by whatever measure, have fewer rights than “productive” people. Such assumptions were at the heart of a great many involuntary eugenics programs, which aimed at improving the genetic quality of the human population by policing and manipulation reproduction.

Eugenics programs are expressions of a mistaken, fallacious interpretation of evolutionary theory, which came to be known as “Social Darwinism.” Eugenics programs were widespread in the early twentieth century, and many were explicitly based on claims derived from evolutionary theory, such that only the strong should survive (Paul 2006).

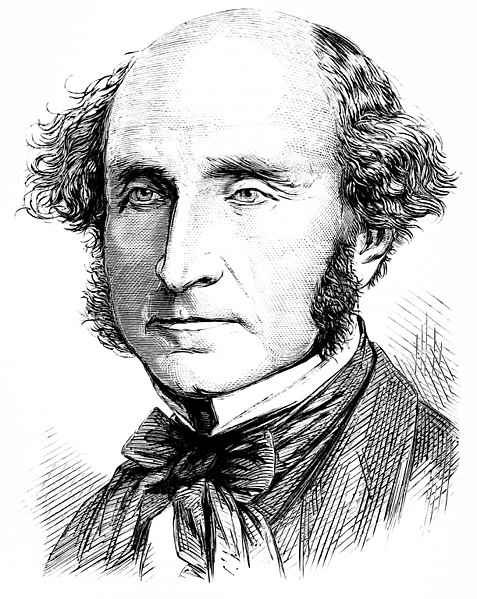

However, such thinking betrays an argumentative fallacy known as an “appeal to nature.” For example, arguing that the use of contraceptives is morally wrong because they prevent the “natural” outcome of intercourse or that men should not do household chores because it is not in their nature are appeals to nature. Appeals to nature can be fallacious in mistakenly identifying something as “natural”—the example of men doing household chores illustrates this. Appeals to nature are fallacious in a strict logical sense, too, because they make an illegitimate step from is to ought. The illegitimacy of deriving an ought from an is has been emphasized by the Scottish philosopher David Hume, and we can call the prohibition against doing so Hume’s Law. Hume remarked:

In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remark’d, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surpriz’d to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence. (Hume [1738] 2007, 302)

Hume deplores the unexplained, imperceptible change from is to ought in a moral argument, and such imperceptible and illegitimate steps were plentiful in some of the arguments by early proponents of evolutionary ethics. The problem was that Spencer and his followers sought to derive moral principles directly from evolutionary insights. The ferocious opposition to Wilson’s suggestion partly reflects the history of evolutionary ethics, as people feared more crude attempts at deriving an ought from an is.

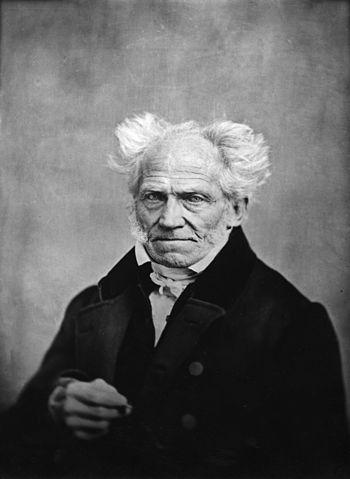

Historically, the demise of early approaches to evolutionary ethics is most closely associated with the British philosopher G. E. Moore, who effectively put an end to the heydays of Spencer’s project in 1903. Moore’s argument provides another instructive objection to evolutionary ethics. Moore charged Spencer and his followers with committing what he called the “naturalistic fallacy” (Moore [1903] 1988, 28). Moore was interested in the definition of “good” and argued that since “good” is a simple property, it cannot be defined by outlining its more basic properties. Thus, identifying “good” with “higher evolved” as Spencer did was to commit the naturalistic fallacy. The impact of what we can call “Moore’s Challenge” has been devastating for evolutionary ethics. More than ninety years after Moore, the philosopher Michael Ruse observes that “it has been enough for the student to murmur the magical phrase ‘naturalistic fallacy’ and then he or she can move on to the next question, confident of having gained full marks thus far on the exam” (Ruse 1995, 220).

There is more to be said both about the strength of Hume’s Law and about Moore’s Challenge in particular. The takeaway at this point is that approaching normative questions about what we ought to do from within evolutionary ethics requires taking on both challenges. The lessons from the first century of evolutionary ethics are that the prospects for deriving normative principles from evolutionary theory are dim.

However, it is important to recognize that evolutionary ethics can still have implications for what we ought to do by telling us about where moral principles apply. To illustrate the difference between establishing moral rules and establishing where moral rules apply, consider norms about blame. It is one thing to establish the moral norm that you are blameworthy if you cause harm or offense when you could have done otherwise, and quite another to establish, in a specific case, whether Peter is blameworthy for using foul language that offended some people: after all, he could have Tourette syndrome, in which case he could not have done otherwise. The project of finding out more about the features that are relevant for moral evaluation, like our psychology, is thus of crucial importance for finding out where moral rules apply (so which specific things we ought to do), though it does not establish the moral rules themselves. It is also a bona fide methodological ethical naturalistic project. Moreover, evolutionary ethics can be very fruitfully applied to other relevant questions within ethics, as we will see in the next sections.

Why are We Moral?

Humans are astonishingly prosocial compared to other animals. The primatologist Sarah Hrdy illustrates this nicely:

Each year 1.6 billion passengers fly to destinations around the world. Patiently we line up to be checked and patted down by someone we’ve never seen before. We file on board an aluminum cylinder and cram our bodies into narrow seats, elbow to elbow, accommodating one another for as long as the flight takes. With nods and resigned smiles, passengers make eye contact and then yield to latecomers pushing past. When a young man wearing a backpack hits me with it as he reaches up to cram his excess paraphernalia into an overhead compartment, instead of grimacing or baring my teeth, I smile (weakly), disguising my irritation….I cannot keep from wondering what would happen if my fellow human passengers suddenly morphed into another species of ape. What if I were traveling with a planeload of chimpanzees? Any one of us would be lucky to disembark with all ten fingers and toes still attached, with the baby still breathing and unmaimed. Bloody earlobes and other appendages would litter the aisles. Compressing so many highly impulsive strangers into a tight space would be a recipe for mayhem. (Hrdy 2011, 1-4)

What Hrdy is getting at is that humans are a moral species, not in the sense that all of us are morally good people (some are crooks, after all) but in the sense that normally functioning adults are capable of following the written and unwritten rules of society so that we can all get along. Importantly, we sometimes follow such rules even in the absence of credible threats of sanctions: sometimes, people return that lost wallet of cash, do not cheat even if they could get away with it, and decide to help people that live in far-away countries. And human children are extraordinarily attuned to attend to social cues—nothing interests them more than other humans, and they seem to be very concerned with fairness and other rules that we could classify as moral. But why are we moral? The philosopher Immanuel Kant famously attributed it to an inborn capacity:

Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and reverence, the more often and more steadily one reflects on them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me. (Kant [1788] 2015, 129)

Referring to our moral sense alone, however, does not get us far along to an answer. For why do we have such a moral sense? After all, it is not only trained moral philosophers that behave respectfully and non-selfishly on airplanes. Examples of this behavior range from the mundane, such as honest behavior in circumstances where cheating would be impossible to detect, to the drastic, such as people that sacrifice their lives for others. How could such behavior have evolved?

Evolutionary ethics in a descriptive sense provides some answers. The hypothesis is that morality is a tool for cooperation. Being able to follow rules, to internalize them, and to stick to them even if it is against your immediate interests is what makes morality something that can be useful from an evolutionary perspective.

There are two competing hypotheses. The first takes a “gene’s eye’s view” on natural selection (Dawkins 2006). According to this view, natural selection occurs only on the level of individual organisms. Metaphorically speaking, think of your own body, and the traits that make it attractive to potential mates, as a vehicle for your genes to copy themselves into the next generation. So, to offer an evolutionary explanation of a certain trait, we have to understand why having that trait would have led to the organism’s spreading more of its genes into the next generation. At first glance, the gene’s eye view makes it puzzling why behavior such as sacrifice in war would evolve. After all, how would sacrificing yourself help you to spread your genes into the next generation? The biologist Richard Hamilton pointed out that behavior towards our kin would be beneficial even from the perspective of a selfish gene because we share many genes with our kin (Hamilton 1963). For example, helping your brother or sister is beneficial from your genes’ point of view, because you share 50% of your genes with your sibling. Of course, we also behave morally toward people outside our family, and so-called reciprocal altruism helps explain how such behavior could have evolved (Trivers 1971). Even though two individuals might be genetically unrelated, it pays for them to benefit the other as long as the favor is returned in the future so that, over the long run, both organisms enjoy individual fitness benefits. Therefore, from the gene’s eye view, our beliefs in obligations and duties, our ability to experience empathy towards others, to understand their intentions, and so forth, is seen as a product of selective pressures on the individual level.

Proponents of group-selectionist theories take a different perspective on the evolution of morality. According to this view, natural selection occurs also on the level of groups (as opposed to only on the level of individual organisms). Group selectionists do not deny the role of selection on the level of the individual, but they emphasize that group selection is a key ingredient in the evolution of morality. As competition for resources between groups of hunter-gatherers intensified around 150,000 years ago, group cohesion and cooperation amongst group members became an important factor. Groups with more cooperative individuals would have a better position in this struggle and, as we have seen, the ability to follow moral rules would be a way to increase cooperation. As groups with more cooperative individuals outcompeted groups with less cooperative individuals, the human population, in general, became more and more attuned to cooperative behavior, and this is why humans began to develop the moral psychology that characterizes us as moral animals today.

There are still many open questions between these two camps, and many concern the central events, processes, or mechanisms that enabled the evolution of morality (see the Cultural Evolution box). At the very least, evolutionary ethics as a descriptive project helps to explain the origins of some of the foundations of morality.

Taboos are interestingly similar to moral norms: they are binding and do not allow for exceptions. The anthropologist John Henrich argues that taboos illustrate how culture played an important role in our evolutionary history (Henrich 2016). For example, for female inhabitants of Yasawa Island (Fiji) it is taboo to eat larger fish such as moray eels, barracuda, or sharks when they are pregnant. The taboo is based on tradition and religious beliefs and adhering to the taboo seems like a significant constraint because the taboo fish make up a large part of the ordinary diet of most Yasawa islanders, including pregnant women.

Why do pregnant Yasawa women remove such an important source of calories from their diet? The short answer is that their culturally transmitted beliefs tell them to do so. That they are on the right track can be understood from the perspective of Western medicine, too. By removing large fish from their menu, pregnant women run a lower risk of ciguatera poisoning. Ciguatera toxin is produced by a marine microorganism and as it gets eaten by small fish, and those fish by yet bigger fish, the toxin produced by the microorganism can reach dangerous levels in large fish like barracuda (Henrich 2016, 128).

Norms about food are transmitted socio-culturally and the anthropologist Joseph Henrich uses the fish-taboo case to illustrate that culture played a crucial role in the evolution of humans and human morality (Henrich 2016, 100-102). Think of culture as a set of explicit or implicit rules and ways of doing things. Culture in this sense is intangible and yet part of our tangible environment: if you violate an implicit rule, others might punish you for it. According to Henrich, “cultural evolution initiated a process of self-domestication, driving genetic evolution to make us prosocial, docile, rule followers who expect a world governed by social norms monitored and enforced by communities (Henrich 2016, 5).

Just as culture in the form of, say, taboos about poisonous food can drive genetic evolution, it may constitute an environment which requires individuals to be attuned to the social rules and thereby favors individuals who are better able to follow the rules. Culture might thus be an important component in the evolution of morality.

Are there Moral Facts?

So far, we have covered how evolutionary ethics relates to the question what we ought to do and why we are moral in the first place. A related set of questions about ethics are metaethical questions, which concern the meaning of moral terms, our ways of gaining knowledge of moral facts, and the nature of the moral facts. In other words, apart from thinking about how we ought to live, and where our moral sense comes from, we can also ask what it means to affirm a particular answer to that question, how we could come to know the answer, and whether the answer would be a matter of fact or more like an opinion.

Many books and articles in moral philosophy start with the observation that moral judgments seem to be objectively true and the assumption that this is how non-philosophers also think about morality. For example, Michael Smith writes:

We seem to think moral questions have correct answers; that the correct answers are made correct by objective moral facts; that moral facts are wholly determined by circumstances; and that, by engaging in moral conversation and argument, we can discover what these objective facts are. (Smith 1994, 6)

But as we have seen above, evolutionary theory explains why we would think that moral judgments are objective. The philosopher Michael Ruse takes this to show that the apparent objectivity of morality is something like an “illusion” foisted on us by our genes (Ruse [1986] 1998, 253). Of course, even if Ruse is correct, this does not show that moral judgments are not objective, but it can make us think whether the objectivity of morality really has to be explained, as many philosophers assume. Ruse has also argued that an evolutionary account of morality suggests that there are no moral facts in the first place. Anything we want to explain about morality can be explained without mentioning moral facts, or so Ruse argues. If moral facts are explanatorily redundant, indeed, moral realists (those who believe there are mind-independent, objective facts about morality, as discussed in Chapter 1) need to say why we should still suppose that moral facts do exist. Interestingly, Ruse’s methodological naturalism leads him to embrace a view that goes against the metaphysical naturalist position that moral facts exist.

Relatedly, Sharon Street, for example, argues that evolutionary explanations of morality show that moral realism is probably false. The kind of moral realism that Street has in mind is the view that moral properties exist as objective features of the world (to wit, whether stealing is wrong is independent of whether anyone thinks or feels that stealing is wrong). Street starts with the premise that our moral judgments are influenced by evolutionary forces. This fact, Street claims, gives rise to a dilemma for moral realists concerning the relation of the evolutionary forces that influenced our moral judgments and the moral facts claimed to exist by moral realists. If there is no relation between the evolutionary forces and the moral facts, then it would be an astonishing coincidence if many of our moral judgments were true. In light of the coincidence, we have no reason to assume that our moral judgments are true—an unpalatable conclusion for realists. Claiming that there is a relation, however, is empirically dubious, according to Street. Mirroring Ruse’s claim, moral facts could be purged from what we assume to exist because they do not perform an important explanatory function. So, we should reject moral realism. Street’s argument illustrates how evolutionary theory can be used to make a case about which metaethical theories we should adopt.

Both Ruse’s and Street’s arguments rely on the idea that we should only accept that something exists if it plays an indispensable explanatory role and there are means to resist these arguments. Both arguments, as presented here, rely on the correctness of the evolutionary explanation of morality they convey. In the next section, we turn to the relevance of evolutionary ethics for moral epistemology.

Can We have Justified Moral Beliefs?

The evolutionary argument by Sharon Street can also be interpreted as an argument about moral justification and moral knowledge. Suppose that moral realists assume that there is no relation between our moral judgments and the moral facts. It would seem like an incredible coincidence if the realists were right that our moral judgments are nonetheless true. There are just too many possible moral truths and too many ways in which evolution could have “pushed” our moral beliefs. Street claims that such a coincidence would be too much to believe. But what is the problem, exactly, with having beliefs that are only coincidentally true? Depending on how we understand “coincidence,” my belief that there is a bird outside my window is coincidentally true because had I looked a little later, the bird would have flown away already. Accidentally true beliefs do not seem problematic in every case. The question for proponents of Street’s argument is to show why the evolutionary influence on human moral beliefs makes for a particularly problematic case of coincidence.

The philosopher Richard Joyce argues that the problem has to do with the sensitivity of our moral beliefs to the moral facts (Joyce 2006). Given that our moral beliefs are influenced by evolutionary forces, and not by the moral facts, our moral beliefs would be the same even if the moral facts would change. But because we should not hold on to such insensitive beliefs, evolutionary explanations of morality show that our moral beliefs are unjustified (because they are not sensitive).

It is not clear, however, whether and why evolutionary explanations of morality reveal something about our moral beliefs that is particularly troubling from an epistemological perspective. The impact of evolutionary ethics on epistemological questions depends on these deeper questions about epistemology. Evolutionary explanations of morality, however, provide us with a useful starting point for thinking about these questions.

Conclusion

Evolutionary ethics has helped us to get a much clearer sense of where the human moral sense is coming from. While this is a far cry from revealing to us what we ought to do, the research program seems full of promise nonetheless. Once we get into the details, we can see that it also raises deep theoretical questions about evolutionary explanations, the relation of descriptive and normative claims, the epistemology of justification and truth, and the general viability of naturalism in ethics. Much left to wonder, then, but with some ideas about where to get our answers.

References

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. 2009. Experiments in Ethics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ayer, A. J. (1936) 1971. Language, Truth, and Logic. London: Penguin Books.

Boyd, Richard. 1988. “How to be a Moral Realist.” Essays on Moral Realism, ed. Geoffrey Sayre-McCord, 181-228. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Brink, David Owen. 1989. Moral Realism and the Foundations of Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buck v. Bell. 274 U.S. 200 (1927).

Clifford, William Kingdon. 1879. Lectures and Essays. London: Macmillan and Co.

Darwin, Charles (1871) 2004. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: Penguin Classics.

Dawkins, Richard. 2006. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, Richard. 2016. The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Doerr, Adam. 2009. “Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough.” Genomics Law Report. http://www.genomicslawreport.com/index.php/2009/06/25/three-generations-of-imbeciles-are-enough/

Enoch, David. 2010. “The Epistemological Challenge to Metanormative Realism: How Best to Understand It, and How to Cope with It.” Philosophical Studies 148(3): 413-438.

Flanagan, Owen. 2017. The Geography of Morals: Varieties of Moral Possibility. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hamilton, William D. 1963. “The Evolution of Altruistic Behavior.” The American Naturalist 97(896): 354–56.

Henrich, Joseph Patrick. 2016. The Secret of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hume, David. (1738) 2007. A Treatise of Human Nature: A Critical Edition, ed. David Fate Norton. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer. 2011. Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Joyce, Richard. 2006. The Evolution of Morality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Joyce, Richard. 2016. “Evolution and Moral Naturalism.” In A Companion to Naturalism, ed. Kelly James Clark. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kant, Immanuel. (1788) 2005. Critique of Practical Reason, trans. Mary Gregor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kitcher, Philip. 2011. The Ethical Project. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Klenk, Michael. 2019. “Objectivist Conditions for Defeat and Evolutionary Debunking Arguments.” Ratio: 1-14.

Mackie, John Leslie. 1977. Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong. New York: Penguin Books.

Moore, George Edward. (1903) 1988. Principia Ethica. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Paul, Diane. “Darwin, Social Darwinism and Eugenics.” In The Cambridge Companion to Darwin, eds. Jonathan Hodge and Gregory Radick, 214-239. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Railton, Peter. 1986. “Moral Realism.” The Philosophical Review 95(2): 163-207.

Railton, Peter. 2017. “Naturalist Realism in Metaethics.” In The Routledge Handbook of Metaethics, eds. Tristram McPherson and David Plunkett, 43-57. New York/London: Routledge.

Ruse, Michael. 1995. Evolutionary Naturalism: Selected Essays. London/New York: Routledge.

Ruse, Michael. (1986) 1998. Taking Darwin Seriously: A Naturalistic Approach to Philosophy. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Ruse, Michael. 2006. “Is Darwinian Metaethics Possible (And If It Is, Is It Well Taken)?” In Evolutionary Ethics and Contemporary Biology, eds. Giovanni Boniolo and Gabriele de Anna, 13-26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, Michael. 1994. The Moral Problem. Malden/Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Segerstrale, Ullica. 2000. Defenders of the Truth: The Sociobiology Debate. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Street, Sharon. 2006. “A Darwinian Dilemma for Realist Theories of Value.” Philosophical Studies 127(1): 109-166.

Tomasello, Michael. 2016. A Natural History of Human Morality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Trivers, Robert L. 1971. “The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 46(1): 35-57.

Wilson, Edward Osborne. 2002. Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Zamzow, Jennifer L., and Shaun Nichols. 2009. “Variations in Ethical Intuitions.” Philosophical Issues 19: 368-388.

Further Reading

Shaw, Tamsin. 2016. “The Psychologists Take Power.” New York Review of Books. February 25. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2016/02/25/the-psychologists-take-power/

Haidt, Jonathan, Steven Pinker, and Tamsin Shaw. 2016. “Moral Psychology: An Exchange.” New York Review of Books. April 7. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2016/04/07/moral-psychology-an-exchange/

“Justification and Explanation.” 2014. Wireless Philosophy. http://www.wi-phi.com/video/justification-and-explanation

Alvarez, Maria. 2017. “Reasons for Action: Justification, Motivation, Explanation.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta.

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/reasons-just-vs-expl