Introduction to Community Psychology by Leonard A. Jason, Olya Glantsman, Jack F. O'Brien, and Kaitlyn N. Ramian (Editors) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Community Psychology by Leonard A. Jason, Olya Glantsman, Jack F. O'Brien, and Kaitlyn N. Ramian (Editors) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

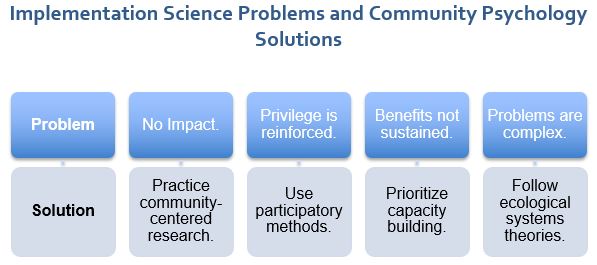

This textbook tells the story of community psychologists, who view social problems as being due to the unequal distribution of resources, which causes poverty, homelessness, unemployment, and crime. In addition, because no condition or disease has ever been eliminated by just dealing with those with the problem, community psychologists focus their work on prevention. Finally, community psychology shifts the power dynamics so that community members are equal members of the team, as they provide unique points of view about barriers that need to be overcome in working toward social justice. In a sense, this field has many similarities with community organizing, but it’s different in that community psychologists have both research and action skills to evaluate whether or not our interventions actually work.

_______________________________________________________________________

This textbook is only supported on Firefox, Chrome, Safari, and Microsoft Edge. Internet Explorer is not compatible with our formatting. We thank Mark Zinn, our front end developer, for his help in uploading and formatting our content.

If you want to be a change agent for social justice, but are not sure how to begin, you have come to the right place. The authors of this Community Psychology textbook will show you how to comprehensively analyze, investigate, and address escalating problems of economic inequality, violence, substance abuse, homelessness, poverty, and racism. As you read through these chapters, you will begin a journey that will provide you with perspectives and tools to promote a fair and equitable allocation of resources and opportunities, resulting in meaningful changes in your community.

Consistent with the liberating ideas of social justice, this Introductory Community Psychology textbook is free, providing an alternative to costly college textbooks that contribute to the rising levels of student debt. We thank the Vincentian Endowment Fund at DePaul University for making this online resource accessible.

In our continuing effort to expand our thinking and outreach, we are able to offer you an opportunity for learning about the field of Community Psychology. Undergraduates can soon become free Student Associate Members within the Society for Community Research and Action, which is the home organization of Community Psychology. We highly encourage you to visit this link to learn more about our field, what it can do for you, and how you can get involved.

Chapter One Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

“If you are unable to understand the cause of a problem,

it is impossible to solve it.”

– Naoto Kan

Most people think of psychologists in very traditional ways. For example, if you were to close your eyes and imagine a psychologist, there is a good chance you would think of a clinician or therapist. Clinical psychologists in their office settings often treat people with psychological problems one at a time by trying to change thought patterns, perceptions, or behavior. This is often called the “medical model” which involves a therapist delivering one-on-one psychotherapy to patients. There is a similar medical model in the field of medicine, and examples of this model would involve a physician fixing a patient’s broken arm or providing antibiotics for an infection. Although there is a clear need for this traditional model for those with medical or psychological problems, many do not have access to these services, and a very different approach will be required to successfully solve many of the individual and community problems that confront us.

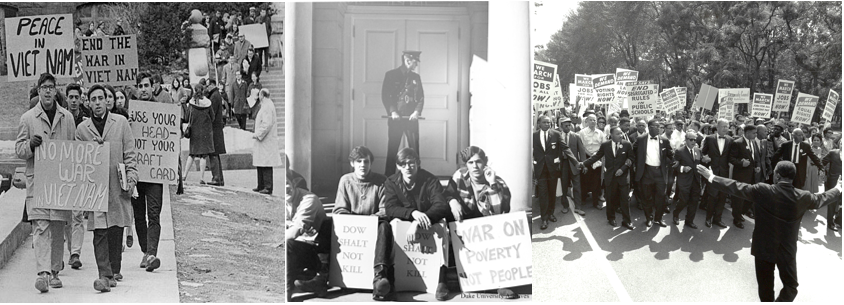

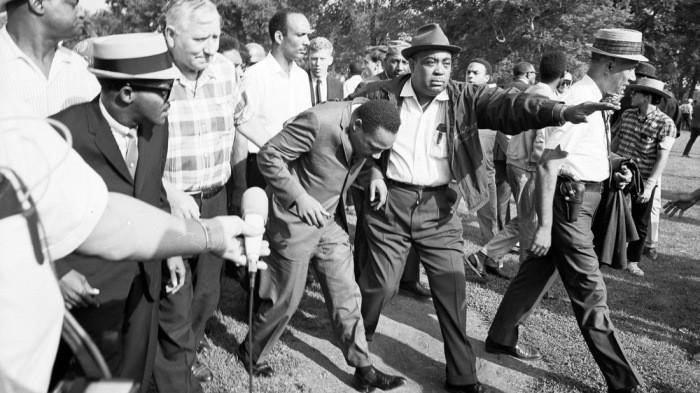

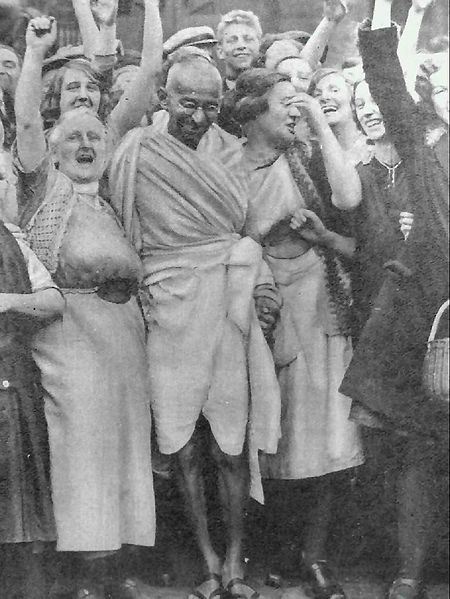

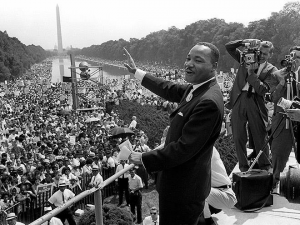

Throughout this textbook you will learn about this different, strength-based approach, called Community Psychology. In the US, it emerged in the 1960s during a time when the nation was faced with protests, demonstrations, urban unrest, and intense struggles over issues such as the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement. Many psychologists wanted to find ways to help solve these pressing societal issues, and some therapists were becoming increasingly disillusioned with their passive role in solely delivering the medical model, office-based psychotherapy (Cowen, 1973). At the 1965 Swampscott Conference in the US, the term “Community Psychology” was first used, and it signaled new roles and opportunities for psychologists by extending the reach of services to those who had been under-represented, focusing on prevention rather than just treatment of psychological problems, and by actively involving community members in the change process (Bennett et al., 1966). Over the past five decades, the field of Community Psychology has matured with recurring themes of prevention, social justice, and an ecological understanding of people within their environments. The goals of Community Psychology have been to examine and better understand complex individual–environment interactions in order to bring about social change, particularly for those who have limited resources and opportunities.

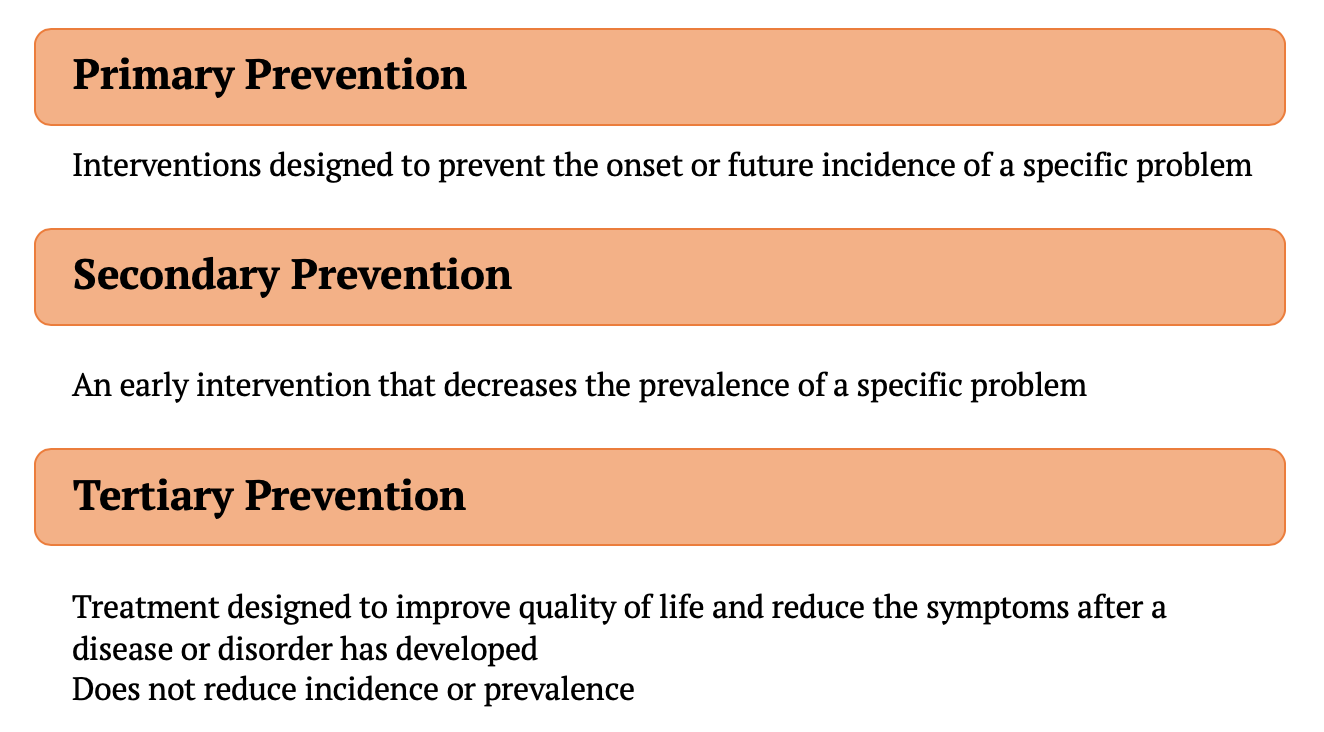

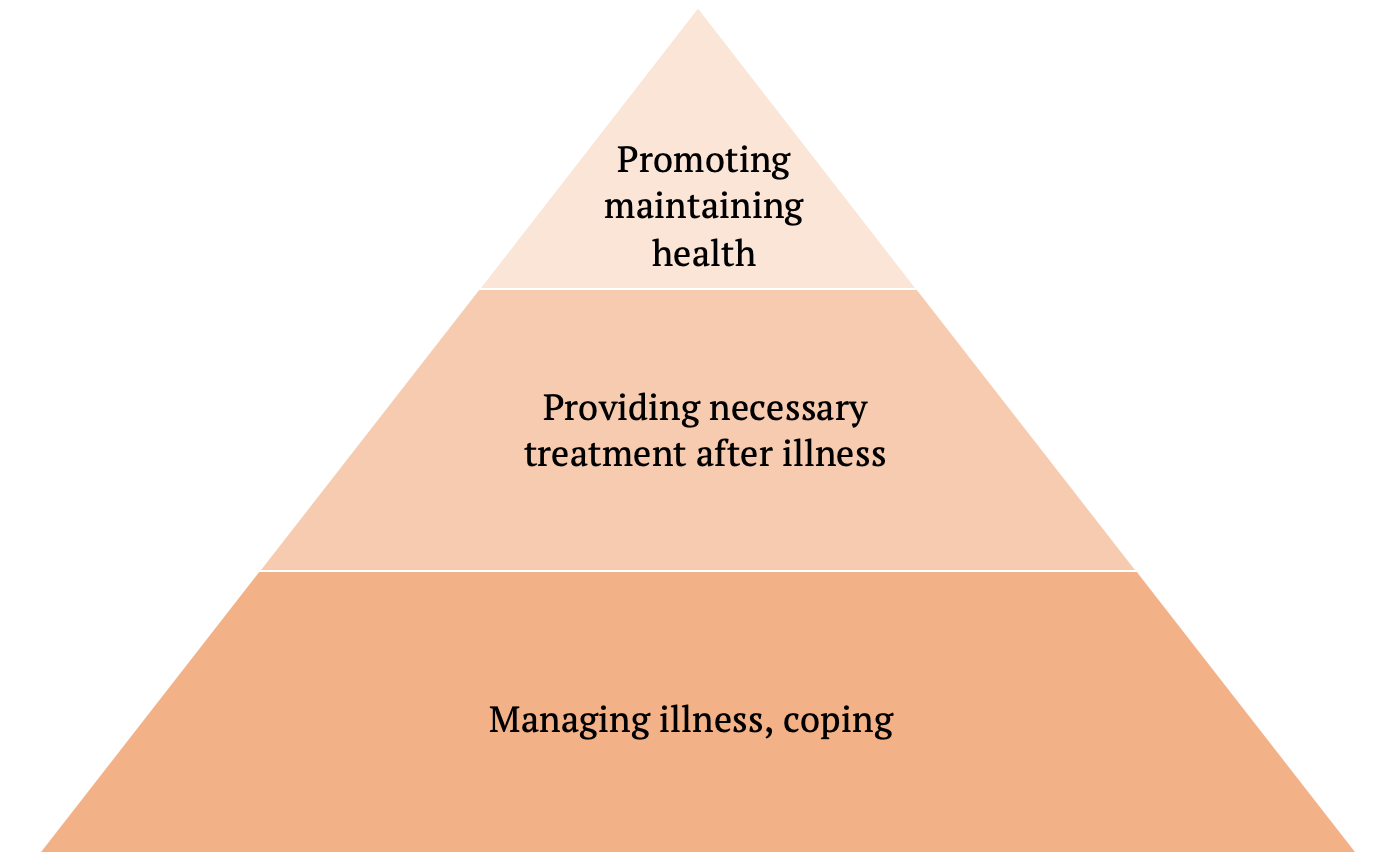

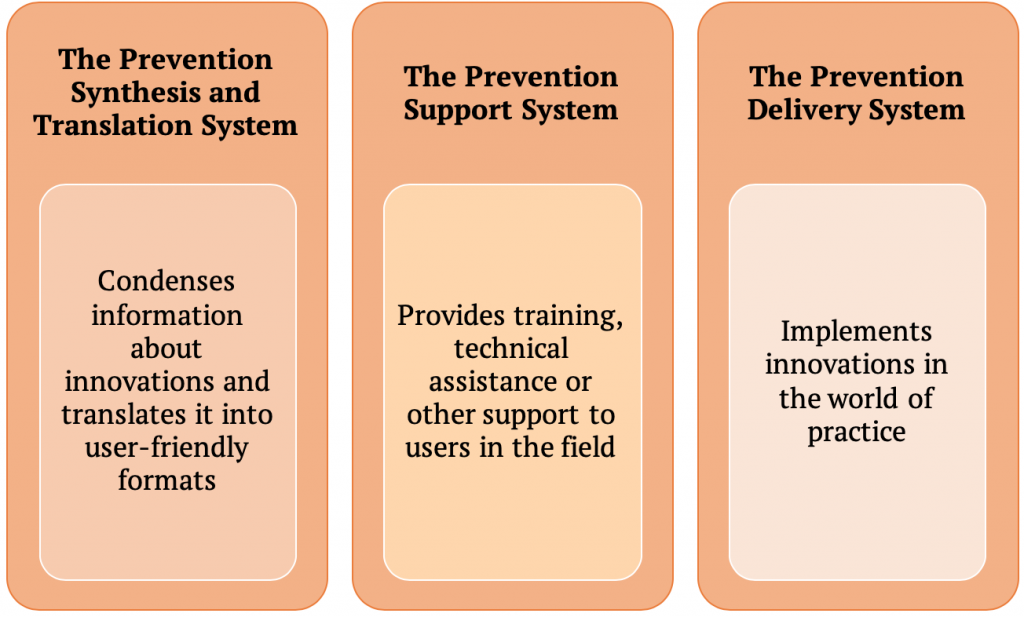

One of the primary characteristics of the Community Psychology field is its focus on preventing rather than just treating psychological problems, and this can occur by boosting individual skills as well as by engaging in environmental change. The example in the box below provides an example of prevention directed toward saving lives at a beach, as drowning is one of the leading causes of death.

Imagine a beautiful lake with a long sandy beach surrounded by high cliffs. You notice a person who fell from one of the cliffs and who is now flailing about in the water. The lifeguard jumps in the water to save him. But then a bit later, another person wades too far into the water and panics as he does not know how to swim, and the lifeguard again dives into the water to save him. This pattern continues day after day, and the lifeguard recognizes that she cannot successfully rescue every person that falls into the water or wades in too deep. The lifeguard thinks that a solution would be to install railings to prevent people from falling from the cliffs and to teach the others on the beach how to swim. The lifeguard then attempts to persuade local officials of the need for railings and swimming lessons. During months of meetings with town officials, several powerful leaders are hesitant about spending the money to fund the needed changes. But the lifeguard is persistent and finally convinces them that scrambling to save someone only after they start to drown is dangerous, and the town officials budget the money to install railings on the cliffs and initiate swimming classes.

This example highlights a key prevention theme in the field of Community Psychology, and in this case, the preventive perspective involved getting to the root of the problem and then securing buy-in from the community in order to secure resources necessary to implement the changes. As illustrated in the textbox above, there are two radically different ways of helping others, which are referred to as first- and second-order change. First-order change attempts to eliminate deficits and problems by focusing exclusively on the individuals. When the lifeguard on the beach dove into the water to save one person after another, this was an example of a first-order intervention. There was no attention to identifying the real causes that contributed to people falling into the water and being at risk for drowning, and this band-aid approach would not provide the structural changes necessary to protect others on the beach or walking on the cliffs. A more effective approach involves second-order change, the strategy the lifeguard ultimately adopted, and this involved installing railings on the cliff and the teaching of swimming skills. Such changes get at the source of the problem and provide more enduring solutions for the entire community. A real example of this approach involved low-income African American preschool children who participated in a preventive learning preschool program (called the High/Scope Perry Preschool)—40 years later, participants in this program were found to have better high school completion, employment, income, and lower criminal behavior (Belfield et al., 2005).

There is a considerable appeal for a preventive approach, particularly as George Albee (1986) has shown that no condition or disease has ever been eliminated by focusing just on those with the problem. Prevention is also strongly endorsed by those in medicine who have been trained in the Public Health model, where services are provided to groups of people at risk for a disease or disorder in order to prevent them from developing it. Public Health practitioners seek to prevent medical problems in large groups of individuals through, for example, immunizations or finding and eliminating the environmental sources of disease outbreaks. Community Psychology has adopted this preventive Public Health approach in its efforts to analyze social problems, in addition to its unique characteristics, which you will read below and throughout this textbook.

An impressive example of prevention occurred with community efforts to change the landscape of tobacco use over the past 60 years. Today, attitudes have changed toward tobacco use, and community organizations aided by community psychologists made important contributions to this second-order change effort that involved reducing tobacco use. This began with the landmark Surgeon General’s Report in the 1960s, which summarized serious health problems caused by smoking. Advocacy groups such as Action on Smoking and Health helped to create non-smoking sections on planes and public transportation, and other organizations used strategies to promote nonsmokers’ rights in public buildings, restaurants, and work areas. Still, other work involved preventive school and community-based interventions as well as efforts to reduce youth access to tobacco, as shown in Case Study 1.1.

Case Study 1.1

Youth Tobacco Prevention

In the 1980s, school students informed community psychologist Leonard Jason that store merchants were openly selling them cigarettes. The students’ critical input was used to launch a study assessing illegal commercial sales of tobacco, and Jason’s team found that 80% of stores in the Chicago metropolitan area sold cigarettes to minors. When results of this study were publicized on the evening television news, Officer Bruce Talbot from the suburban town of Woodridge, Illinois contacted Jason to express interest in working on this community problem. Talbot and the Woodridge police with technical help from Jason’s team collected data showing that the majority of Woodridge merchants sold tobacco to minors. With these data, Woodridge passed legislation that fined both vendors caught illegally selling tobacco and minors found in possession of tobacco. Two years after implementing this program, rates of stores selling to minors decreased from an average of 70% to less than 5%. Woodridge was the first city in the US to demonstrate that cigarette smoking could be effectively decreased through legislation and enforcement. Jason later testified at the tobacco settlement hearings at the House Commerce Subcommittee on Health and Environment. Due to this study, Officer Talbot had become a national authority on illegal sales of cigarettes to minors. Talbot advised communities throughout the country on how to establish effective laws to reduce youth access to tobacco, and he testified at congressional hearings in Washington D.C. in support of the Synar Amendment, which required states to reduce illegal sales of tobacco to minors using similar methods to those developed in Woodridge. Due to the enactment of the Synar Amendment, there has been a 21% nationwide decrease in the odds of tenth graders becoming daily smokers (Jason, 2013).

This case study illustrates how preventive government policies can be fostered by community-based groups, with the support of community psychologists. These are referred to as bottom-up approaches to second-order change, as the policies emerge from concerned individuals, community activists, and coalitions. Community psychologists have clear roles to play in dialoguing and collaborating with community groups in these types of broad-based, preventive community change efforts.

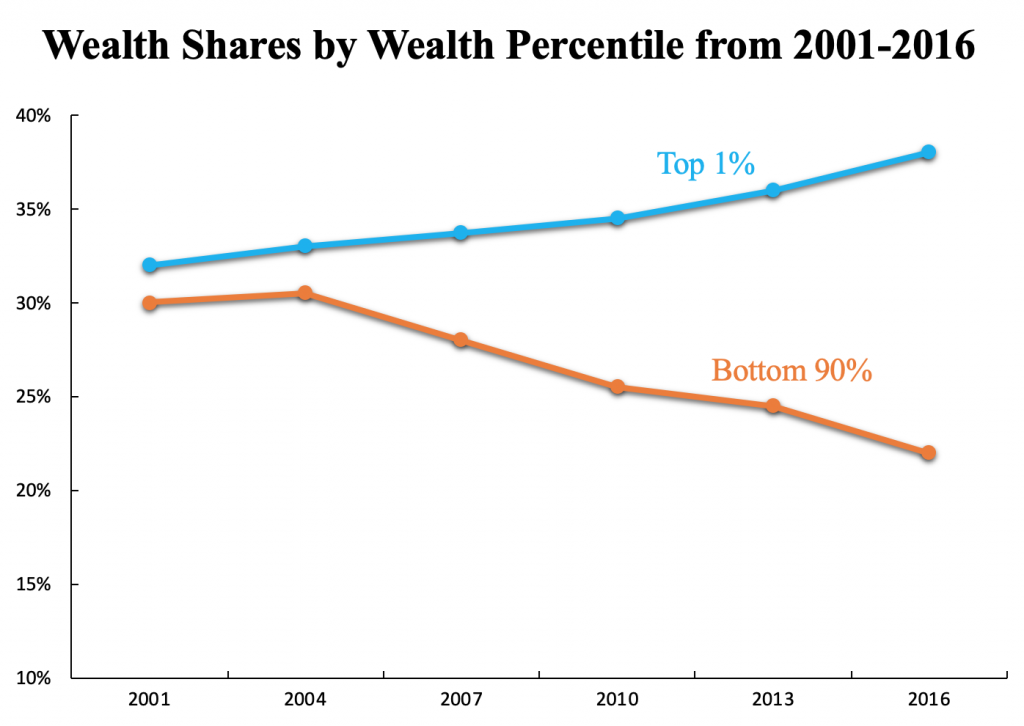

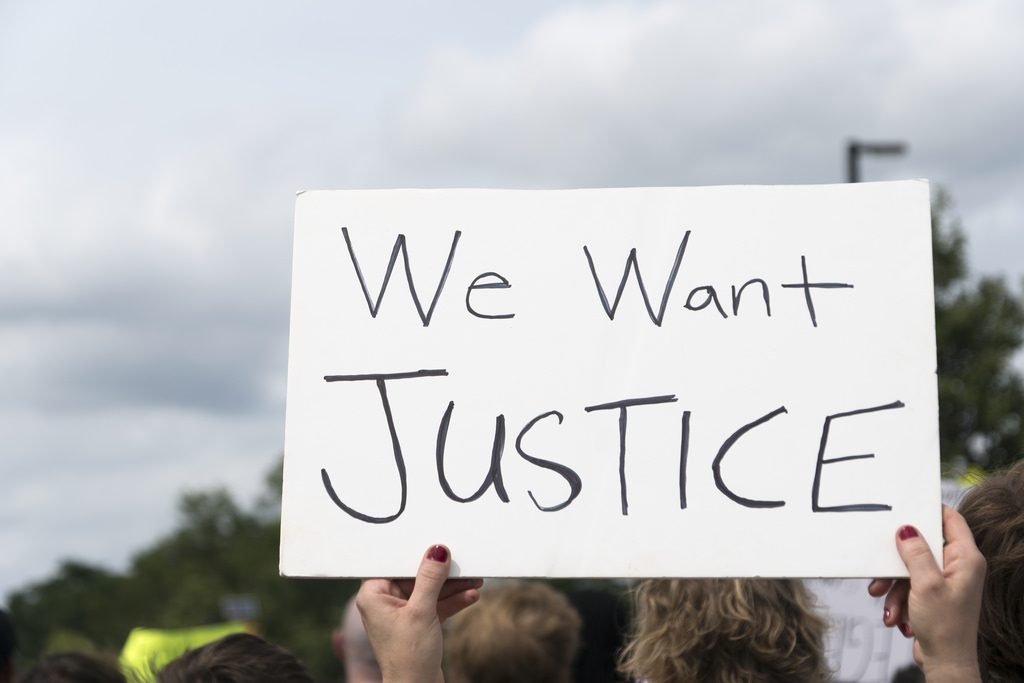

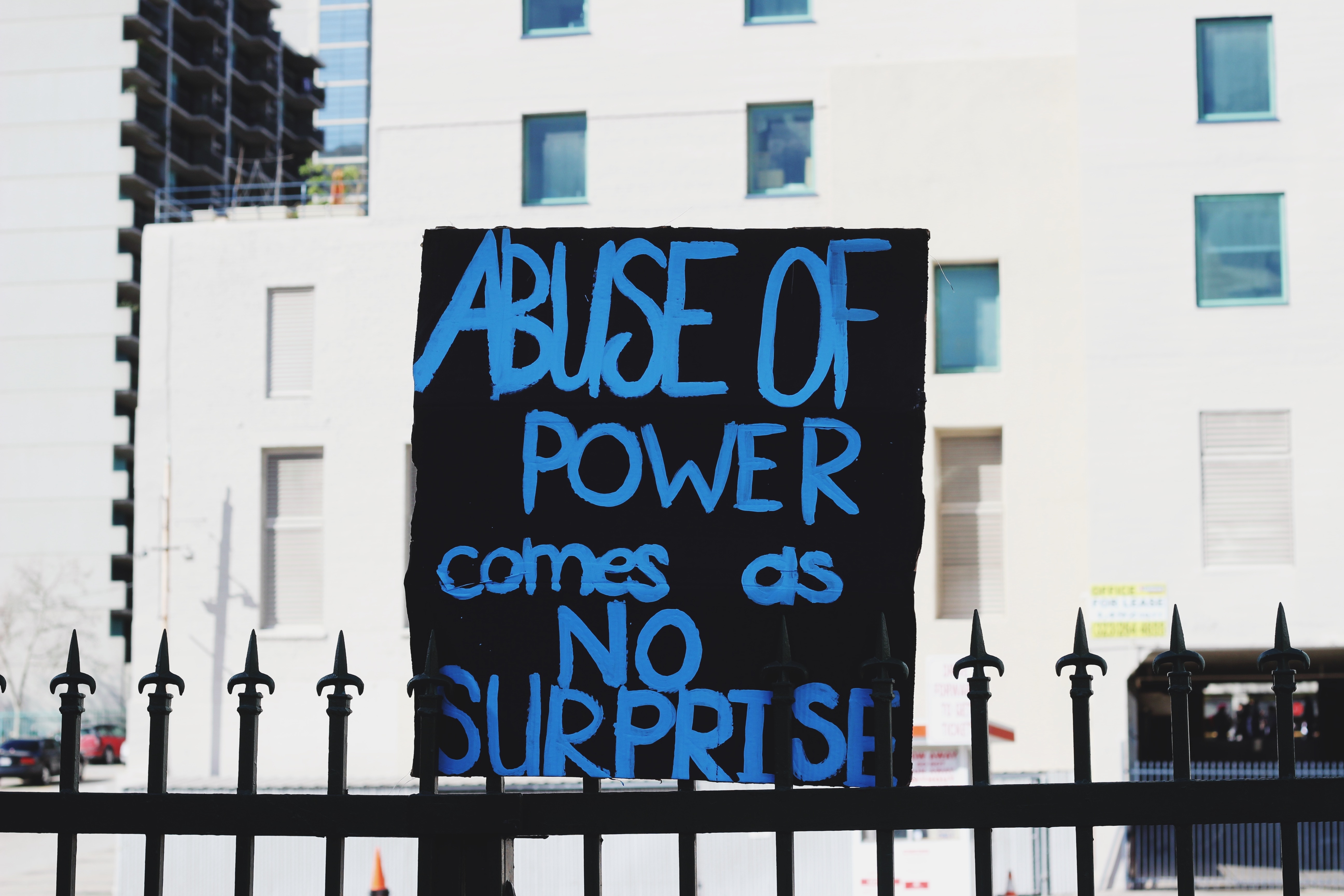

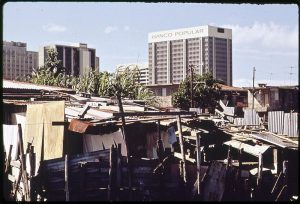

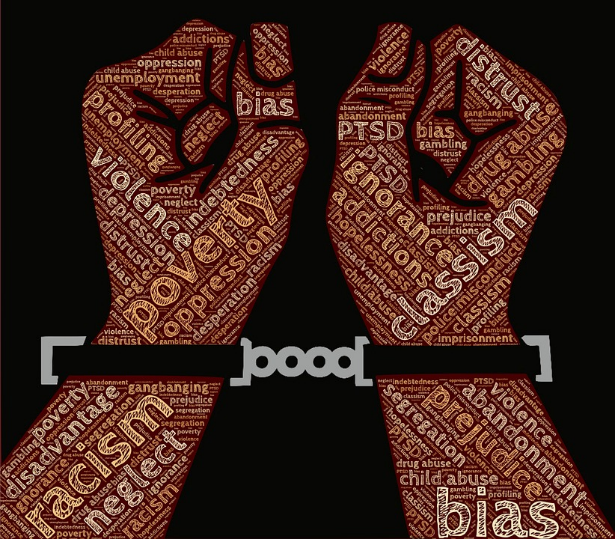

Community Psychology’s focus on social justice is due to the recognition that many of our social problems are perpetuated when resources are disproportionately allocated throughout our society; this causes social and economic inequalities such as poverty, homelessness, underemployment and unemployment, and crime. Albee (1986) has concluded that societal factors such as unemployment, racism, sexism, and exploitation are the major causes of mental illness. In support of this, Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett’s (2009) book The Spirit Level documents how many health and social problems are caused by large inequalities throughout our societal structure. Economic inequalities not only cause stress and anxiety but also lead to more serious health problems. Studies of income inequality have shown how adult incomes have varied by race and gender, and this link allows you to make comparisons that provide animations for any combination of race, gender, income type, and household income level. Clearly, we need to look beyond the individual in exploring the basis of many of our social problems. Yet, most mental health professionals, including psychologists, have a tendency to try to solve mental health problems without attending to these environmental factors.

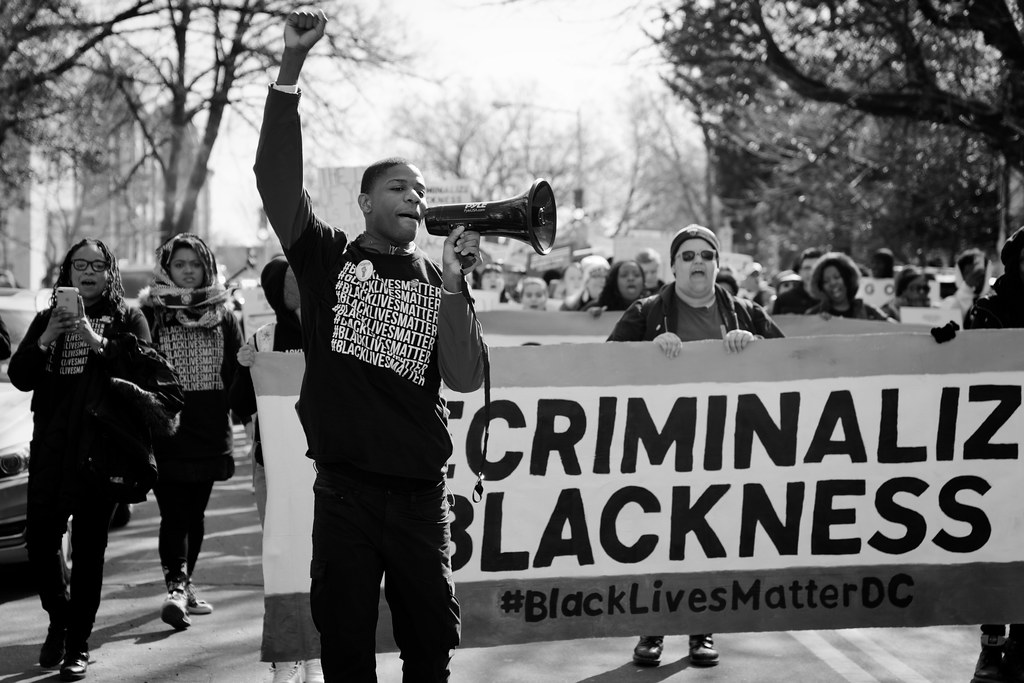

Community Psychology endorses a social justice and critical psychology perspective which looks at how oppressive social systems preserve classism, sexism, racism, homophobia, and other forms of discrimination and domination that perpetuate social injustice (Kagan, 2011). Clearly, there is a need to bring about a better society by dismantling unjust systems such as racism. In addition to identifying and combating systems that are unjust, community psychologists also challenge more subtle negative practices supported by psychological research and practice. For example, a person with a social justice orientation would object to imposing intervention manuals, based on white middle-class norms, on low-income minority students. Such materials would not be applicable or appropriate to the lived experiences of minority students.

The need for this social justice orientation is also evident when working with urban schools that are dealing with a lack of resources, overcrowded classrooms, community gang activity, and violence. Traditional mental health services such as therapy that deals with a student’s mental health issues would not address the income resource inequalities and stressful environmental factors that could be causing children’s mental health difficulties. Second-order change strategies, in contrast, would address the systems and structures causing the problems and might involve collaborative partnerships to bring more resources to the school as well as support community-based efforts to reduce gang activity and violence. As an example, Zimmerman and colleagues investigated what it takes to cultivate a safe environment where youth can grow up in a safe and healthy context (Heinze et al., 2018). These community psychologists found that improving physical features of neighborhoods such as fixing abandoned housing, cutting long grass, picking up trash, and planting a garden resulted in nearly 40% fewer assaults and violent crimes than street segments with vacant, abandoned lots.

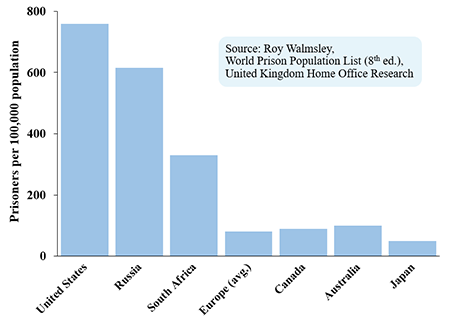

This social justice perspective can also be used to examine the institutionalization of millions of individuals in the US criminal justice system. According to an individualistic perspective, people end up in prison because of factors such as mental illness, substance abuse, or a history of domestic violence. On the other hand, the Community Psychology social justice perspective posits that larger, structural forces (e.g., political, cultural, environmental, and institutional factors) need to be considered. A social justice perspective recognizes that millions of people have been locked up in US prisons due to more restrictive and punishing laws (such as mandatory minimums, and three-strikes which requires lifetime prison sentences), and there have been changes in how we have also dealt with patients in mental institutions. Through the 1960s and 1970s, many state-run mental hospitals were closed, which meant that discharged patients were supposed to be treated in our communities. However, funding to support these community-based treatment programs was significantly reduced in the 1980s, and as a consequence, many former patients of mental institutions became homeless or involved with the criminal justice system. Unfortunately, our prison system became the new settings where mentally ill people were warehoused. This is an example of first–order change, which has involved shifting mental patients from one inadequate institutional setting to another. Adopting a social justice perspective clearly broadens our understanding as to why millions of people in the US are incarcerated.

The tragedy of being forced to live in overcrowded and unsafe prisons is further compounded by the way 600,000 or more prison inmates are released back into communities in the US. Most prisons have at best meager rehabilitation programs, so most inmates have not been adequately prepared for transitioning back into our communities. Clearly, criminally justice-involved people need more than weekly psychotherapy provided by traditional clinical psychologists.

Individuals who are released from jail uniformly state their greatest needs are for safe housing and employment but are rarely provided these critical resources. Given these circumstances, we should not be surprised that so many released inmates soon return to prison. A moving story by Scott about his heroin addiction and prison experiences is in Case Study 1.2.

Case Study 1.2

A Chance for Change through Oxford House

“I was born to an addicted mother who was a heroin addict and meth user as well. She left when I was 2 and I’ve only seen my mother one time when I was 17. I was adopted by my grandparents and was raised in a great family. I grew up having the best things in life and I was a standout sports player in high school until my life took a turn – for the worst. I dabbled with drugs and, after an injury that caused me to never play again, I turned to drugs. I became addicted to cocaine and meth and painkillers. Thinking I had it all under control, I caught my first felony and was sent to prison at 19. I became a prison gang member and later on was a gang leader of one of the most dangerous and second-largest gangs in the United States prison system. Once released after two years, I got out and didn’t know how to readjust to living normal. I started using Heroin and my life and addiction became the worst. Nineteen days later I was charged with an organized crime case and after bonding out, I went to treatment but never took it seriously. I was just addicted to the money and power I possessed and, no matter how much my family begged me to just stop, I went back to shooting dope… I was given a 7-year sentence and I served six and a half years at the deadly Ferguson unit here in Texas. Five years of that I spent in solitary confinement, locked down 23 hours a day due to my gang affiliations and actions in prison where I continued to use drugs and was just as much strung out as if I was still in the world. In 2013, I was paroled back home. I only lasted five months and was indicted on 2 first-degree felonies and offered 80 years. I went to jury trial where I was found not guilty but ended up with another indictment that I signed a five-year sentence for. I did four years, eight months, on that charge and was released back home in 2018. I lasted 2 days until I relapsed once again [on] heroin and on July 24, I did the last shot of heroin I’ll ever do. I overdosed and died in the ambulance only to be brought back and I woke up in Red River Detox, beat down and broken. I was there when I saw Philip and Cristen came to do a presentation. As I listened to Philip tell his story, I saw myself in him and realized that this is what I want. I wanted to finally make it and live a real life so I got into Oxford House where I’m sober today, working have my family back in my life and holding my head up high each day because I can stand to look at the man in the mirror. I owe this to Oxford Chapter 14; they have saved my life and now I’m Re-Entry coordinator and have a chance to help people like me get a chance of making it. Thank you, Oxford House” (Oxford House Commemorative Program, 2018, page 57).

This case study shows that the social justice needs for individuals coming out of prison include community-based programs that provide stable housing, new connections in terms of friends, and opportunities to earn money from legal sources. Oxford House, which is mentioned in this case study, is a community-based innovation for re-integrating people back into the community. The Oxford House network was started by people in recovery with just one house in 1975, and today it is the largest residential self-help organization that provides housing to over 20,000 people in cities and states throughout the US. The houses are always rented, and house members completely self-govern these homes without any help from professionals. Residents can live in these Oxford Houses indefinitely, as long as they remain abstinent, follow the house rules, and pay a weekly rent of about $100 to $120 per week. Oxford Houses represent the types of promising social and community grassroots efforts that can offer people coming out of prisons and substance abuse treatment programs a chance to live in an environment where everyone is working, not using drugs, and behaving responsibly. Best part of all is that this program is self-supporting, as the residents rather than prison or drug abuse professionals are in charge of running each home. Here, the residents use their income from working to pay for all house expenses including rent and food (this video illustrates the Oxford House approach in a brief segment on the 60 Minutes TV broadcast). There are these types of innovative grassroots organizations throughout our communities, and community psychologists have key roles to play in helping to document the outcomes of these true incubators of social innovation, as illustrated on this link.

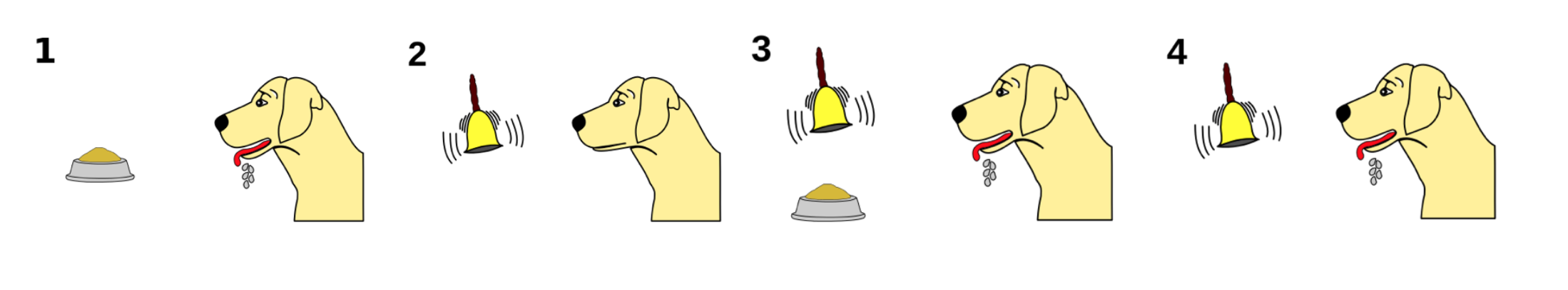

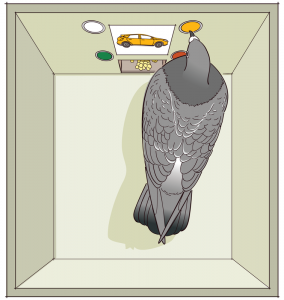

The prevention and social justice examples that we have provided above about installing railings at the cliff to prevent people from accidentally falling into the water or providing housing for those exiting from prison are examples of changing the environment or context. In fact, there is now considerable basic laboratory research that indicates that context or environment can have a shaping influence on the lives of humans and animals. For example, laboratory rats who are raised in “enriched” environments show brain weight increases of 7-10% (heavier and thicker cerebral cortexes) in comparison to those in “impoverished” environments (Diamond, 1988). There was a time when scientists did not believe that the brain could be changed by any environmental enrichment, but it is now commonly accepted that context can have a lasting and shaping influence on our behavior and even our brains. We need to attend to the environments of those living in poverty and exposed to high levels of crime, as these factors are associated with multiple negative outcomes including higher rates of chronic health conditions.

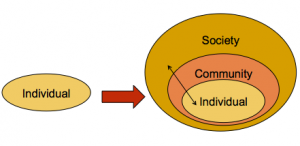

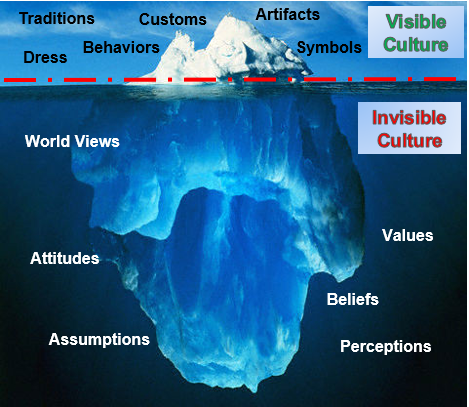

An aspect of Community Psychology that sets it apart from a more traditional Clinical Psychology is a shift beyond an individualistic perspective. Community psychologists consider how individuals, communities, and societies are interconnected, rather than focusing solely on the individual. As a result, the context or environment is considered an integral part when trying to understand and work with communities and individuals embedded in them.

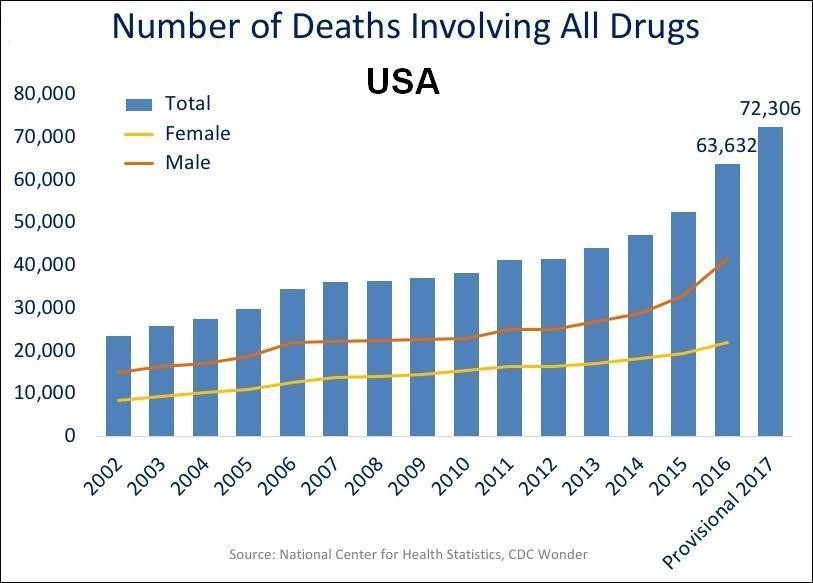

This shift in thinking is referred to as an ecological perspective. Ecological means that there are multiple levels or layers of issues that need to be considered, including the individual, family, neighborhood, community, and policies at the national level. For example, let’s continue our examination of the criminal justice system with another case example. A person, who we shall call Jane, had been involved in an auto accident causing severe pain, and subsequently became addicted to painkillers. When it became more difficult to purchase these medications, she began using heroin to reduce the pain, became involved in buying and selling illegal substances, became estranged from her family, and was caught and sentenced to prison. At the individual level, Jane is certainly distressed and addicted to painkillers, and this has now disrupted relationships with her family and friends. But an ecological perspective would point to a number of factors beyond the individual and group level contributing to this unfortunate situation. Health care organizations contributed to this problem, as many physicians were all too willing to profit by overprescribing pain medications to their patients. The pharmaceutical industry was part of the problem as they reaped huge profits by oversupplying these drugs to pharmacies. At the community level, the criminal justice system also shares blame for delivering punishment in crowded, unsafe prisons for individuals clearly in need of substance use treatment. Finally, at a societal level, federal regulators allowed opiate drugs like OxyContin to be sold for long-term rather than just short-term use, and legislators inappropriately passed laws extending sentences for those who are in prison due to offenses caused by substance use disorders. These types of difficult and complex social problems are produced and maintained by multiple ecological influences, and corrective second–order community solutions will have to deal with these contextual issues.

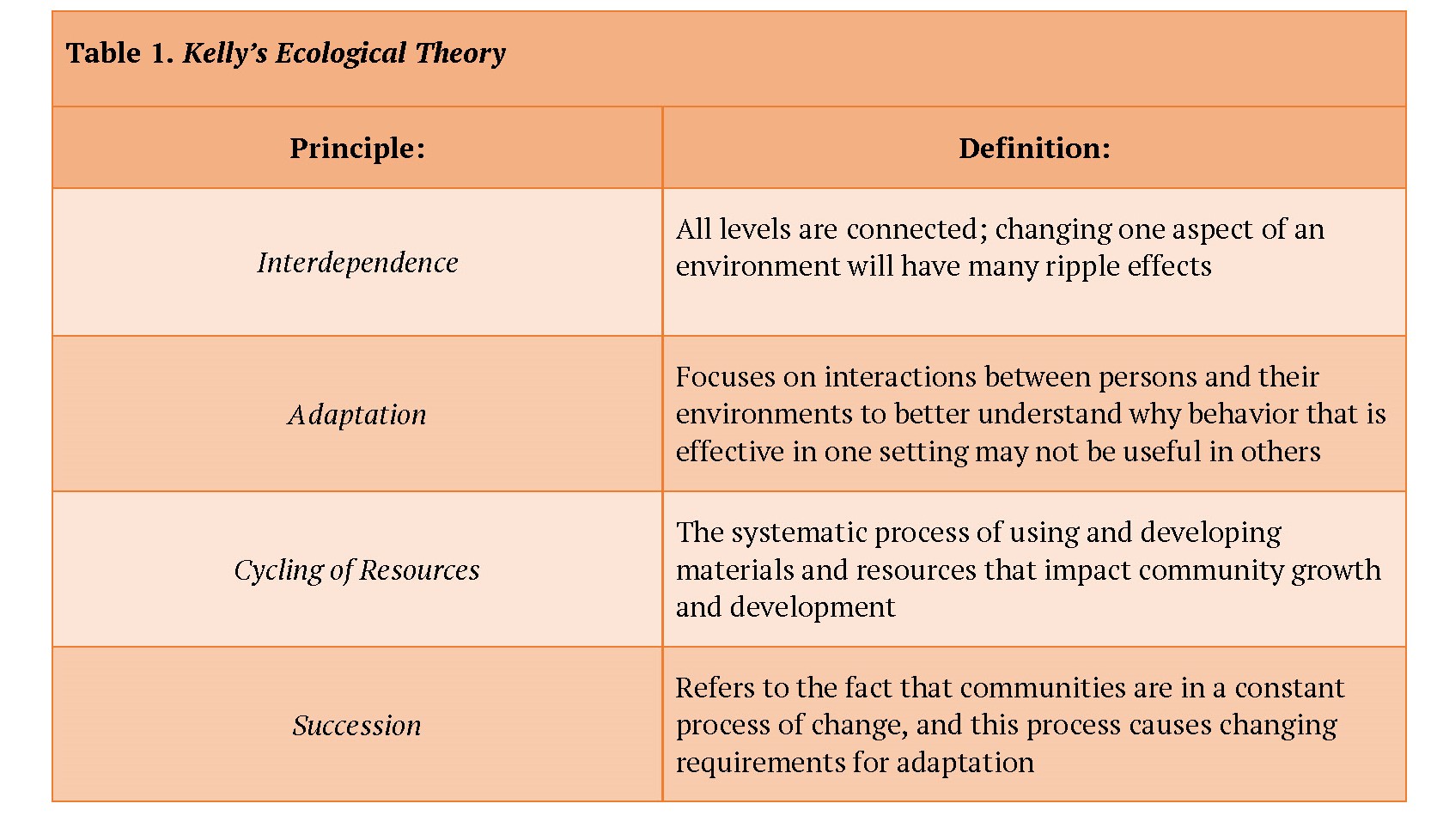

In addition to thinking about these multiple ecological levels, the community psychologist James Kelly (2006) has proposed several useful principles that help us better understand how social environments affect people. For example, the ecological principle of “interdependence” indicates that everything is connected, so changing one aspect of a setting or environment will have many ripple effects. For example, if you provide those released from prison a safe place to live with others who are gainfully employed (as occurs in Oxford Houses), this setting can then lead to positive behavior changes. Living among others in recovery provides a gentle but powerful influence for spending more time in work settings in order to pay for rent and less time in environments with high levels of illegal activities. The ecological principle of “adaptation” indicates that behavior adaptive in one setting may not be adaptive in other settings. A person who was highly skilled at selling drugs and stealing will find that these behaviors are not adaptive or successful in a sober living house, so the person will have to learn new interpersonal skills that are adaptive in this recovery setting. The ecological perspective broadens the focus beyond individuals to include their context or environment, by requiring us to think about how organizations, neighborhoods, communities, and societies are structured as systems.

This ecological perspective helps us move beyond an individualistic orientation for understanding many of our significant social problems such as homelessness, which in the US affects over a half a million people (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2018). At the individual level, many of these individuals do suffer from substance abuse and mental health problems, and they often cycle in and out of the criminal justice system. However, the ecological perspective would focus attention on the lack of affordable housing for low-income people, and thus call for higher-order interventions that go beyond the individual. As an example, Housing First is an innovative intervention founded by clinical-community psychologist Sam Tsemberis, which provides the homeless a home first and then treatment services. This Community Psychology intervention is based on the belief that by providing housing first, there will be many positive ripple effects that lead to beneficial changes in the formerly homeless person’s behaviors and functioning. In this video link, Sam talks about the founding of Housing First innovation, which is a model now used throughout the US.

In Case Study 1.3 below is the story of Russell, who used the Housing First program to find a home and successfully integrate back into the community.

Case Study 1.3

Pathways to Housing: Russell’s Story

“Russell grew up in Southeast DC before becoming homeless more than three decades ago. Struggling with schizophrenia, Russell was in and out of jail and the hospital. He spent the last ten years sleeping on a park bench downtown. This fall, with the help of his Pathways team, Russell moved off the streets and into a permanent apartment. For the first time since 1980, Russell finally has a roof over his head and a place to call home. His favorite thing about the new space? “The television.” A die-hard Washington Redskins fan, Russell is thrilled to be able to cheer his team on—hopefully all the way to the Super Bowl—from the comfort of his living room. For Russell though, it is more than just watching his favorite team play. After just two months, Russell is beginning to thrive in his new home. He has accomplished a number of personal goals including saving to buy a new bike (Russell is a former DC courier) and attending his first-ever Nationals game. Because of you, Russell will not be out in the cold this winter” (Pathways to Housing: Russell’s Story).

The ecological perspective provides an opportunity to examine the issues associated with homelessness beyond the individual level of analysis. Through this framework, we can understand homelessness within complicated personal, organizational, and community systems. In the case of Russell described in the above case study, at the individual level he was dealing with chronic stress, poor health, and mental illness, and felt hopeless. But his sense of despair was in part due to a group level factor, which was the lack of available support from friends or family members. Providing him temporary shelter at night and access to food kitchens represented first-order, individualistic solutions that had never been successful. The Housing First innovation was at a higher environmental level, and once placed in this permanent supportive setting, it had ripple effects on Russell’s sense of hope, connection with others, and ultimately his improved quality of life. Outcome studies have indicated that Housing First is successful in helping vulnerable individuals gain the resources to overcome homelessness, and this program was included in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs.

This ecologic perspective can also be applied to more preventive interventions, such as when Thompson and Jason (1988) stopped gang recruitment by providing urban youth anti-gang classroom sessions and after-school activities that consisted of organized sports clinics that encouraged intragroup cooperation as well as opportunities to travel out of their neighborhood to participate in events and activities with similar groups from other locations. However, those only provided the person-centered anti-gang classroom sessions were still vulnerable to being recruited by gangs after school. There are many examples of how a multi-scale, ecological systems model of people-environment transactions can broaden our understanding of societal problems (Stokols, 2018).

There are other key features of the field of Community Psychology, as will be described in the subsequent chapters, and below we briefly review them.

Community Psychology has a respect for diversity and appreciates the views and norms of groups from different ethnic or racial backgrounds, as well as those of different genders, sexual orientations, and levels of abilities or disabilities. Community psychologists work to counter oppression that is due to racism (white persons have access to resources and opportunities not available to ethnic minorities), sexism (discrimination directed at women), heterosexism (discrimination toward non-heterosexuals), and ableism (discrimination toward those with physical or mental disabilities). The task of creating a more equitable society should not fall on the shoulders of those who have directly experienced its inequalities, including ethnic minorities, the disabled, and other underprivileged populations. Being sensitive to issues of diversity is critical in designing interventions, and if preventive interventions are culturally-tailored to meet the diverse needs of the recipients, they are more likely to be appreciated, valued, and maintained over time.

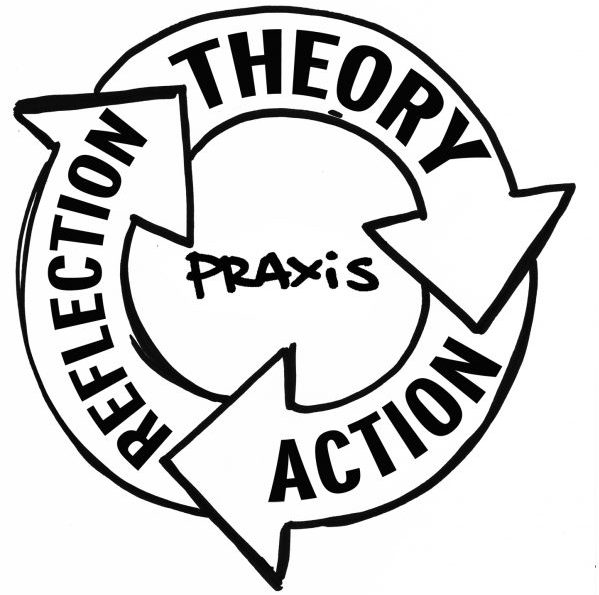

Paulo Freire (1970) wrote that change efforts begin by helping people identify the issues they have strong feelings about, and that community members should be part of the search for solutions through active citizen participation. Involving community groups and community members in an egalitarian partnership is one means of enabling people to re-establish power and control over the obstacles or barriers they confront. When our community partners are recognized as experts, they are able to advocate for themselves as well as for others, as indicated in Case Study 1.1 that described how Officer Talbot became an activist for reducing youth access to tobacco. Individuals build valuable skills when they help define issues, provide solutions, and have a voice in decisions that ultimately affect them and their community. This Community Psychology approach shifts the power dynamic to a less hierarchical, more equal relationship, as all parties participate in the decision-making. Community members are seen as resources who provide unique points of view about the community and the institutional barriers that might need to be overcome in social justice interventions. All partners are involved equally in the research process in what is called community-based participatory research.

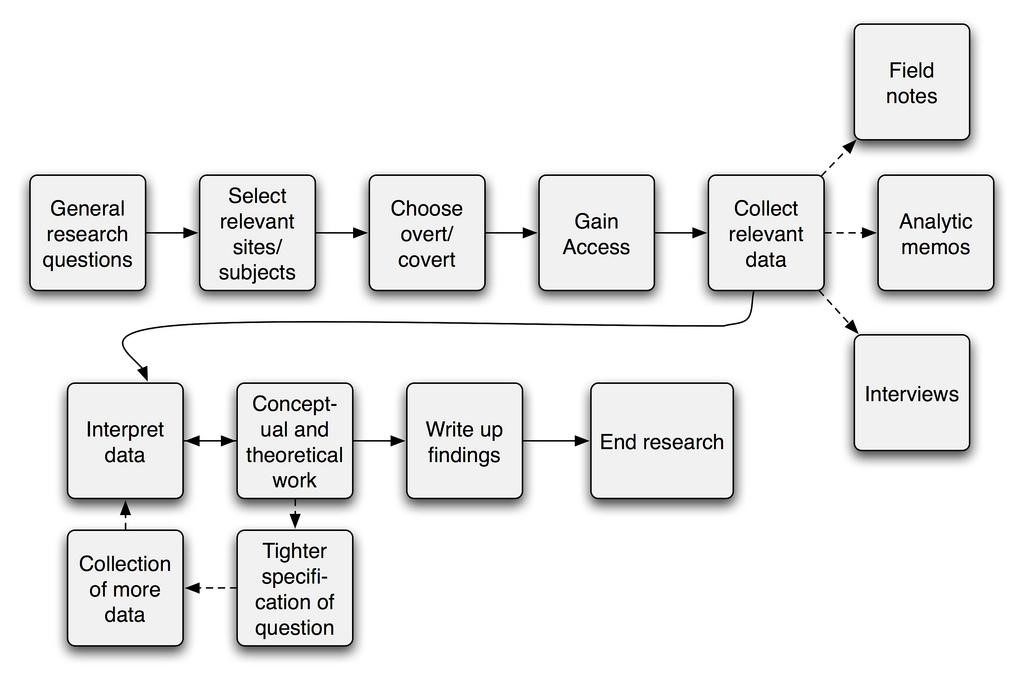

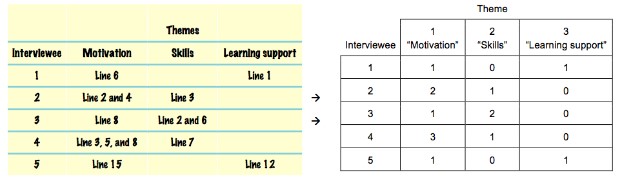

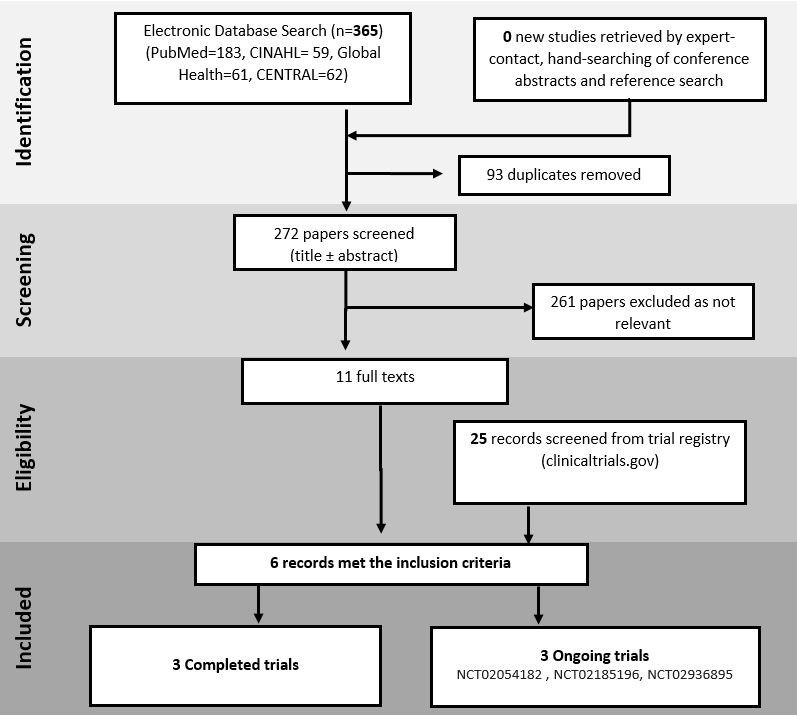

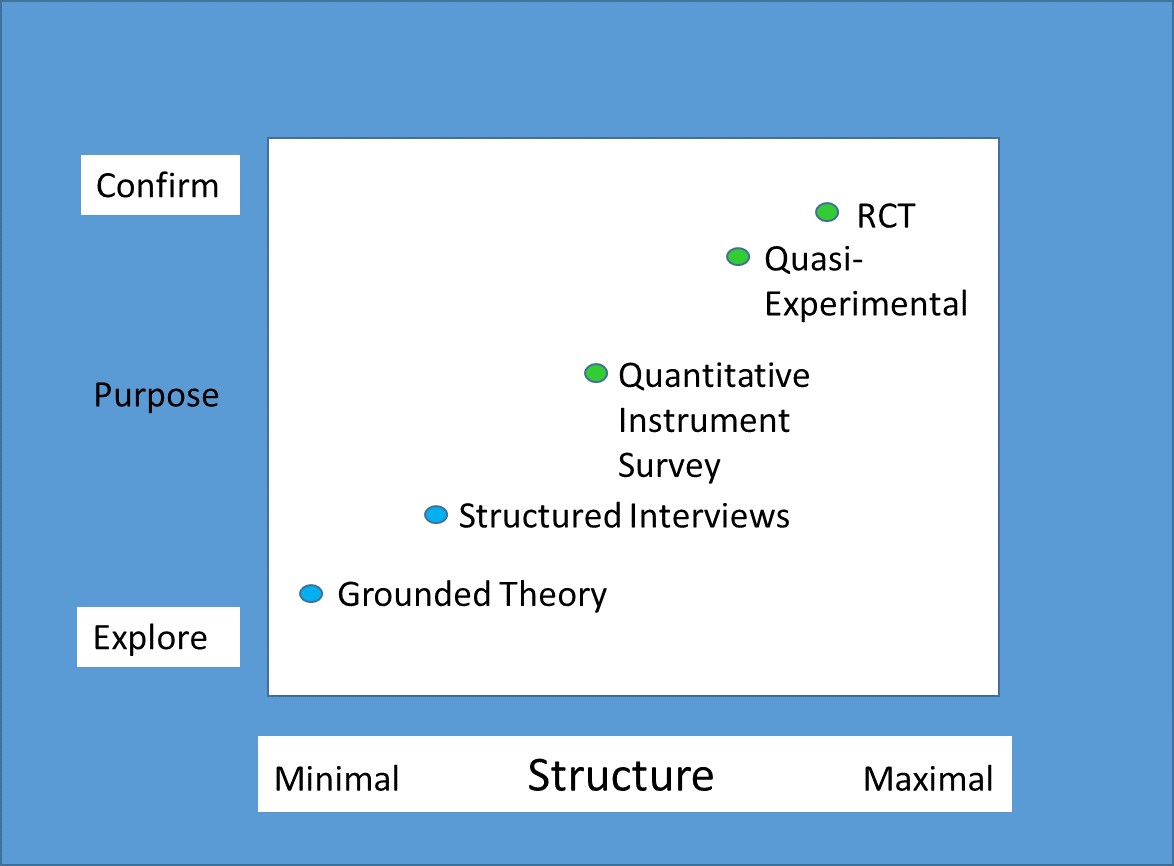

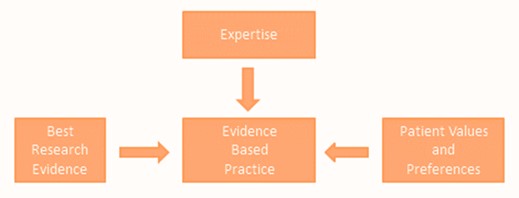

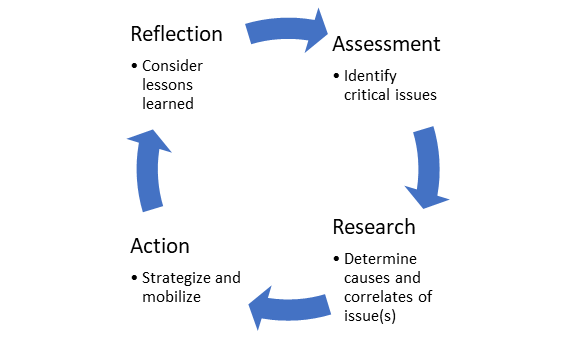

In striving to understand the relationship between social systems and individual well-being, community psychologists base advocacy and social change on data that are generated from research and apply a number of evaluation tools to conceptualize and understand these complex ecological issues. Community psychologists believe that it is important to evaluate whether their policy and social change preventive interventions have been successful in meeting their objectives, and the voice of the community should be brought into these evaluation efforts. They conduct community-based action-oriented research and often employ multiple methods including what are called qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research (Jason & Glenwick, 2016). No one method is superior to another, and what is needed is a match between the research methods and the nature of the questions asked by the community members and researchers. Community psychologists, like Durlak and Pachan (2012), have used adventuresome research methods to investigate the effects of hundreds of programs dedicated to preventing mental health problems in children and adolescents, and the findings showed positive outcomes in terms of improved competence, adjustment, and reduced problems.

Social issues are complex and intertwined throughout every fiber of our society, as pointed out by the ecological perspective. When working with individuals who have been marginalized and oppressed, it is important to recognize that issues such as addiction and homelessness require expertise from many perspectives. Community Psychology promotes interdisciplinary collaboration with professionals from a diverse array of fields. For example, a community psychologist helped put together the multidisciplinary team evaluating Oxford House efforts to help re-integrate individuals with substance use problems back into the community. One member of the team was a sociologist who studies social networks, and one of the important findings was that the best predictor of positive long-term outcomes was having at least one friend in the recovery houses. Also, part of this team was an economist who found that the economic benefits were greater, and costs were less for this Oxford House community intervention than an intervention delivered by professionals. Other important contributions were made by a social worker, a Public Health researcher, Oxford House members, and undergraduate and graduate students who each contributed unique skills and valuable perspectives to the research team. You can see how these types of collaborations can emerge by using the idea tree exercise, which different disciplines can work together to create new ideas and advance knowledge across fields.

One of the core values of Community Psychology is the key role of psychological sense of community, which describes our need for a supportive network of people on which we can depend. Promoting a healthy sense of community is one of the overarching goals of Community Psychology, as a loss of connectedness lies at the root of many of our social problems. So understanding how to promote a sense of belonging, interdependence, and mutual commitment is integral to achieving second-order change. If people feel that they exist within a larger interdependent network, they are more willing to commit to and even make personal sacrifices for that group to bring about long-term social changes. From a Community Psychology perspective, an intervention would be considered unsuccessful if it increased students’ achievement test scores but fostered competition and rivalry that damaged their sense of community.

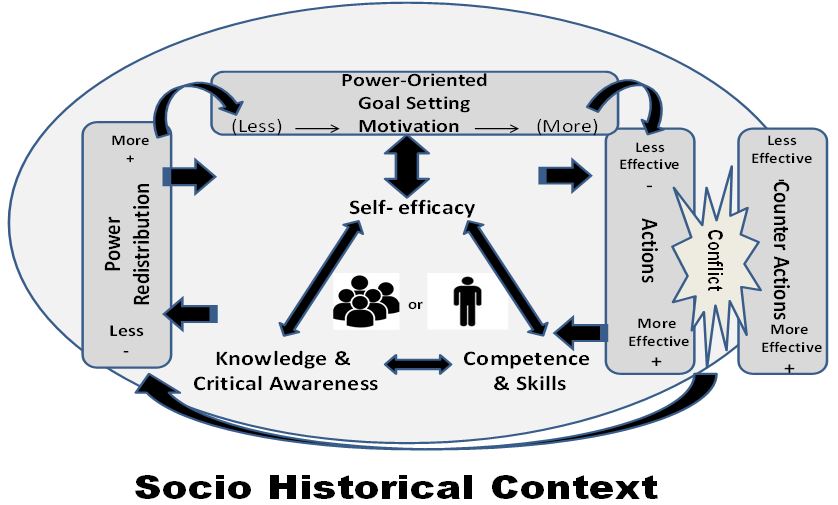

Another important feature of Community Psychology is empowerment, defined as the process by which people and communities who have historically not had control over their lives become masters of their own fate. People and communities who are empowered have greater autonomy and self-determination, gain more access to resources, participate in community decision-making, and begin to work toward changing oppressive community and societal conditions. As shown in Case Study 1.3, individuals such as Russell who have been homeless often feel a lack of control over their lives. However, once provided stable housing and connections with others, they feel more empowered and able to gain the needed resources to improve the quality of their lives.

Community psychologists also enter the policy arena by trying to influence laws and regulations, as illustrated by the work on reducing minors’ access to tobacco described in Case Study 1.1. Community psychologists have made valuable contributions at local, state, national, and international levels by collaborating with community-based organizations and serving as senior policy advisors. It is through policy work that over the last century, the length of the human lifespan has doubled, poverty has dropped by over 50%, and child and infant mortality rates have been reduced by 90%.

Over the next decades, there is a need for policy-level interventions to help overcome dilemmas such as escalating population growth (as this will create more demands on our planet’s limited drinking water, energy, and food resources), growing inequalities between the highest and lowest compensated workers (which will increasingly lead to societal strains and discontent as automation and artificial intelligence will eliminate many jobs), increasing temperatures due to the burning of fossil fuels (which will result in higher sea levels and more destructive hurricanes), and the expanding needs of our growing elderly population. The principles of Community Psychology that have been successfully used to change policy at the local and community level might also be employed to deal with these more global issues that are impacting us now, and will increasingly do so in the future. This video link shows what is possible when we reflect upon policy.

Finally, the promotion of wellness is another feature of Community Psychology. Wellness is not simply the stereotypical lack of illness, but rather the combination of physical, psychological, and social health, including attainment of personal goals and well-being. Furthermore, Community Psychology applies this concept to also include groups of people, and communities—in a sense, collective wellness.

This chapter has reviewed the key features of the Community Psychology field, including its emphasis on prevention, its social justice orientation, and its shift to a more ecological perspective. The case studies presented in this chapter illustrate ways in which community psychologists have engaged in systemic and structural changes toward social justice. Students who read the chapters of this textbook will learn how we can mount in community-based research and practices that emphasize fair and equitable allocation of resources and opportunities. This social justice perspective of Community Psychology recognizes inequalities that often exist in our society. Our field works toward providing greater access to resources and decision making, particularly for communities that have been marginalized and oppressed.

Critical Thought Questions

Take the Chapter 1 Quiz

View the Chapter 1 Lecture Slides

____________________________________________________________________

Albee, G. (1986). Toward a just society. Lessons from observations on the primary prevention of psychopathology. The American Psychologist, 41(8), 891-898. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.41.8.891

Badger, E., Miller, C. C., Pearce, A., & Quealy, K. (2018). Income mobility charts for girls, Asian-Americans and other groups. Or make your own. The New York Times, The Upshot. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/27/upshot/make-your-own-mobility-animation.html

Brickler, J., Dettling, L. J., Henriques, A., Hsu, J. W., Jacobs, L., Moore, K. B., …Windle, R. A. (2017, September). Changes in U.S. family finances from 2013 to 2016: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Bulletin. Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/scf17.pdf

Belfield, C., Barnett, W., & Schweinhart, L. (2005). Lifetime effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool study through age 40 (Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, no. 14). Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press.

Bennett, C. C., Anderson, L. S., Cooper, S., Hassol, L., Klein, D. C., & Rosenblum, G. (1966). Community Psychology: A report of the Boston Conference on the Education of Psychologists for Community Mental Health. Boston, MA: Boston University Press.

Cowen, E. (1973). Social and community interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 24(1), 423–472.

Diamond, M.C. (1988). Enriching heredity: The impact of the environment on the anatomy of the brain. New York, NY: Free Press.

Durlak, J. A., & Pachan, M. (2012). Meta-analysis in community-oriented research. In. L. A. Jason & D. S. Glenwick (Eds.), Methodological approaches to community-based research. (pp. 111-122). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Herder and Herder.

Heinze, J. E., Krusky-Morey, A., Vagi, K. J., Reischl, T. M., Franzen, S., Pruett, N. K., …Zimmerman, M. A. (2018). Busy streets theory: The effects of community-engaged greening on violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(1-2), 101-109. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12270

Jason, L. A. (2013). Principles of social change. (pp. 17-21). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Jason, L. A. & Glenwick, D. S. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kagan, C., Burton, M., Duckett, P., Lawthom, R., & Siddiquee, A. (Eds.). (2011). Critical Community Psychology (1st ed.). West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kelly, J. G. (2006). Being ecological: An expedition into Community Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Oxford House, Inc. (2018). Oxford House Recovery Stories. 2018 Annual Oxford House World Convention. Kansas City, Missouri.

Pathways to Housing: Russell’s story. Retrieved from https://www.pathwaystohousingdc.org/stories/russell

Stokols, D. (2018). Social ecology in the digital age: Solving complex problems in a globalized world. London, UK: Academic Press. Retrieved from https://www.elsevier.com/books/social-ecology-in-the-digital-age/stokols/978-0-12-803113-1

State of homelessness. National Alliance to End Homelessness. Retrieved from https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness-report/

Thompson, D. W., & Jason, L. A. (1988). Street gangs and preventive interventions. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 15, 323-333.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2009). The spirit level: Why more equal societies almost always do better. Essex, England: Allen Lane.

Interests into Action with SCRA!

SCRA has several interest groups that provide networking opportunities and diverse ways to pursue interests that matter to you. Find out more at here!

Acknowledgments: We wish to thank Bridget Harris and Laura Sklansky for their superb help in editing this chapter, as well as Mark Zinn for his expert assistance with helping us overcome a wide range of internet and computer problems.

Chapter Two Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

Any historical account (whether it involves politics, culture, or a profession) is bound to be subjective, so it makes sense that much of the history of the field of Community Psychology will also be subjective. Most existing Introductory Community Psychology textbooks (Jason, Glantsman, O’Brien, & Ramian, 2019; Kloos, Hill, Thomas, Wandersman, Elias, & Dalton, 2012; Moritsugu, Duffy, Vera, & Wong, 2019) begin by discussing the social, political, scientific, and professional contexts that influenced the development of the field. Although we will review some of this history briefly, we will focus mainly on the past 50-plus years, since the term Community Psychology was first used by those attending what we now call the “Swampscott Conference” of 1965 (Bennett et al., 1966).

One needs to consider the social and political events of the 1960s in understanding the beginnings of Community Psychology. These were turbulent times, marked with protests and demonstrations involving the Civil Rights movement in the US. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act, an important accomplishment of the Civil Rights Movement, was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. The Feminist Movement was also developing momentum during the 1960s and into the 1970s, as would a similar rights movement for gays and lesbians, the environmental movement, and widespread protests against the Vietnam war. This socially-conscious atmosphere was ideal for the development of the field of Community Psychology, whose values emphasized social justice.

During this time, there also was widespread deinstitutionalization of mental patients, as various media accounts portrayed horrendous conditions in mental hospitals. The development of antipsychotic medications such as Thorazine and the growing research evidence on the harmful effects of mental hospitalization (e.g., Goffman) were key factors in this movement. In 1961, the report of the Joint Commission on Mental Health and Illness was released, which recommended that we reduce the size of mental hospitals and train more professionals and paraprofessionals to meet the largely unmet need for mental health services in our society (Bloom, 1975). These recommendations, vigorously championed by President Kennedy, led directly to the passage of the 1963 Community Mental Health Centers Act, which established community-based services widely throughout the nation. The Community Mental Health Movement was gaining momentum and many large state mental hospitals across the nation would be closed in the next 20 years. With these developments in the background, it was in 1965 that a group of clinical psychologists gathered in Swampscott, MA, and gave birth to the field of Community Psychology, which they hoped would allow them to become social change agents to address many of these pressing social justice issues of the 1960s. Click on this link for a more comprehensive description of events that led up to the Swampscott Conference.

In the years immediately after the 1965 Swampscott Conference, a number of training programs in community mental health and Community Psychology developed. For example, Ed Zolik established one of the first clinical-community doctoral programs in the US at DePaul University in 1966. A free-standing doctoral program was also established in 1966 at the University of Texas at Austin by Ira Iscoe. By 1969, there were 50 programs offering some training in Community Psychology and community mental health, and by 1975 there were 141 graduate programs offering training in these areas.

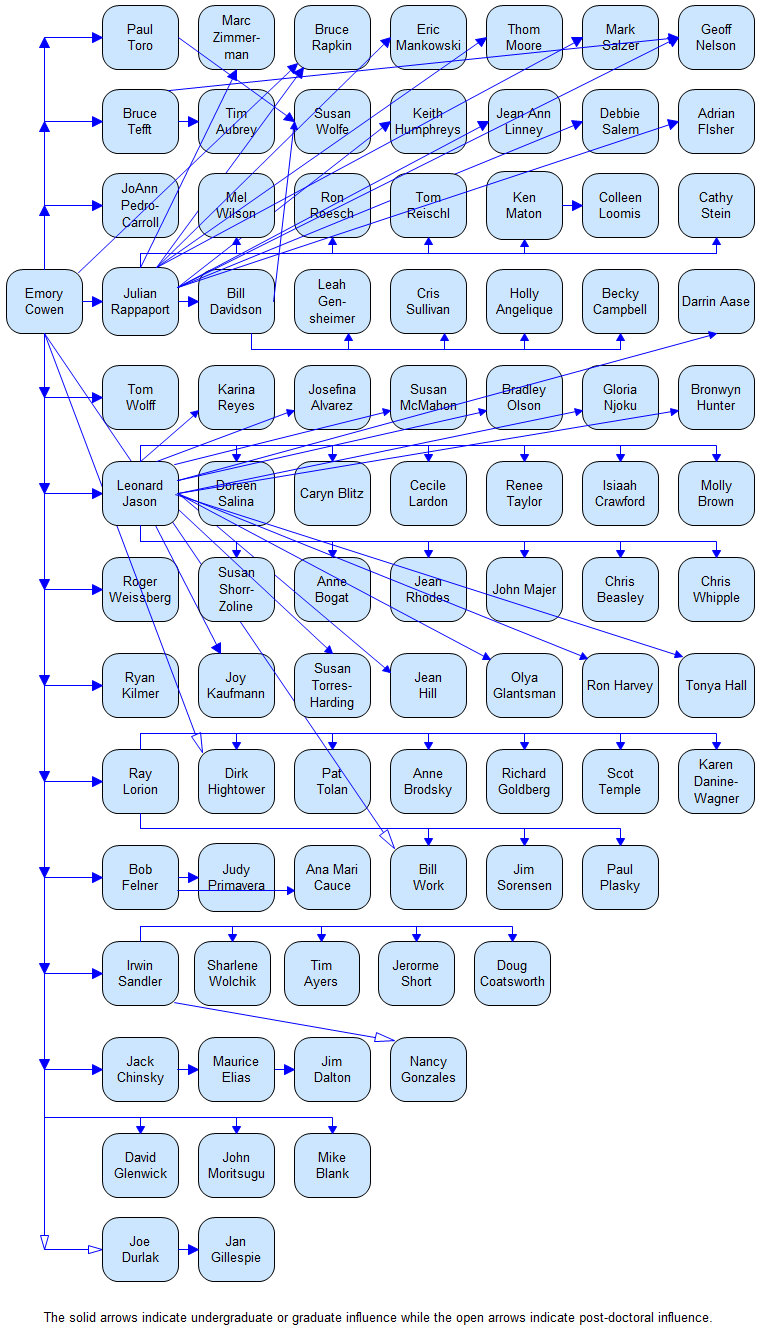

Several important “early settings” for community research and action also developed, often in connection with one of the training programs. These settings included the Primary Mental Health Project at the University of Rochester, founded by Emory Cowen (1975) (click here to see a video of Cowen describing this innovative program). The Primary Mental Health Project identified children in the primary grades (K-3) showing some initial trouble adjusting to school and provided help through the school year from paraprofessional child associates. Cowen, his graduate students, and staff built this intervention for a single school in Rochester in 1958 and it is used by 2,000 schools worldwide today. The Primary Mental Health Project was one of the first widely researched and publicized prevention programs developed by community psychologists. Cowen provided training for a large number of people who later would become prominent in Community Psychology (below is Cowen’s “family tree” initially developed by Fowler & Toro, 2008a).

The Community Lodge project, initially developed by George Fairweather at a Veteran’s Administration psychiatric hospital, was another of these important “early settings.” The Lodge provided an alternative to traditional psychiatric care by preparing groups of hospitalized mental patients in a shared housing environment for simultaneous release into the community. The released patients established a common business to support themselves (e.g., a lawn care service) and eventually took full control of the Lodge project from the professionals who helped them establish the Lodge initially. The first rigorous evaluation of the Lodge found that patients randomly assigned to the Lodge spent less time in a hospital than those in the control group who received traditional services (see Fairweather et al., 1969). Fairweather later helped to establish the doctoral program in Ecological Psychology at Michigan State University and also provided training for many community psychologists.

In 1966, just a year after the Swampscott conference, Division 27 (Community Psychology) of the American Psychological Association (APA) was established. Shortly after, James Kelly (1966), one of the Swampscott attendees and another “founder” of Community Psychology, published an article on the ecological perspective in the widely circulated American Psychologist. Like Cowen and Fairweather, Kelly has been important in training a large number of community psychologists.

The Journal of Community Psychology and the American Journal of Community Psychology were both first published in 1973. These journals have become the two most influential professional journals in the field. The first Community Psychology textbooks came out during the field’s first decade (Bloom, 1975; Zax & Spector). Both of these texts viewed Community Psychology as an outgrowth of the broader field of Clinical Psychology. Over time, the field would portray Community Psychology in a much broader context, deriving from many other sources in addition to Clinical Psychology. Other important publications of this first decade included Ryan’s Blaming the Victim (still, today, one of the most cited publications in the field) and Cowen’s Annual Review of Psychology chapter on social and community interventions. At the end of this decade, the Austin Conference was an opportunity to bring together the key figures in this field during the first 10 years, and provide informal opportunities to examine the field’s conceptual independence from clinical psychology.

The late 1970s and early 1980s could be considered the “heyday” of Community Psychology. During this time period, the political climate made Community Psychology both relevant and necessary, and membership in the US in APA’s Division 27 (Community Psychology) rose to over 1,800 in 1983 (Toro, 2005, p.10).

The first Midwest Ecological Community Psychology Conference took place in 1978 at Michigan State University. This conference provided an opportunity for like-minded community psychologists and students to get together informally to discuss new developments, new training programs, and new research. This conference has now expanded beyond the Midwest to other regions of the US. These conferences have provided a new generation of community psychologists opportunities to put their theoretical ideas about collaboration, empowerment, and the creation of health-promoting settings into practice in their own environments. For a history of these conferences, see Flores, Jason, Adeoye, Evans, Brown, and Belyaev-Glantsman. Case Study 2.1 provides more information about students assuming a major role in the conference’s organization over time.

Case Study 2.1

Students Assume Leadership Roles at the Midwest Ecological Community Psychology Conference

Professors planned and organized the first few informal Midwest Ecological Community Psychology Conferences, but something very special happened in 1980 at the conference at Bowling Green State University. At the end of that meeting, several community psychologists were in a room discussing who would host next year’s event, when a graduate student in the room spoke up suggesting that because the conference was meant for graduate students, then the students should be planning and organizing it. Following this suggestion, students from the University of Illinois Chicago began the long-standing tradition of these conferences being student-run. The Midwest Ecological Community Psychology Conferences have kept going since then with student leadership. This informal support system has led to many networking opportunities over the years for faculty and students to get to know each other, and it has led to many job and training opportunities. As an example, at one of these meetings, Stephen Fawcett was invited to participate in a session to demonstrate how behavioral approaches could be integrated into the field of Community Psychology. Fawcett brought two of his graduate students, Yolanda Suarez-Balcazar and Fabricio Balcazar, and both had a chance to meet Chris Keys at the meeting. This contact eventually led to both graduate students finding their first jobs in Chicago. This is just one example of the networking that continues to lead to important professional and personal relationships among attendees of this student-run conference.

During this second decade, many community psychologists in the US became dissatisfied with the field of Community Psychology’s association as one of APA’s many Divisions. There was a desire to bring more non-psychologists into the field. In addition, there were concerns about APA increasingly emphasizing clinical practice issues over all others. Also, there was a recognition that the term “psychology” no longer fit well with the work of many community psychologists. The group’s organizational name was then changed to the Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA), and the first Biennial Conference on Community Research and Action occurred in 1987. Though many community psychologists still remain members of APA and its Division 27, SCRA now has more non-APA members than ones who belong to APA; the Biennial has become the major national professional venue for Community Psychology.

Looking back on this second decade, this was a time of “soul searching” in the field of Community Psychology, the separation from APA and the initiation of the Biennial Conference both being signs of this. Another sign came from a string of “dueling addresses.” Different community psychologists were trying to strongly encourage the field to adopt one particular emphasis. In his Presidential address to the field of Community Psychology, Emory Cowen argued for prevention to become “front and center” in the field. A few years later, Julian Rappaport argued for an emphasis on empowerment rather than prevention. Ed Trickett argued for an emphasis on an ecological perspective in the field, as did James Kelly. Kelly’s ecological analysis sought to understand behavior in the context of individual, family, peer, and community influences. Prevention, empowerment, and the ecological perspective are three of the most important aspects of the world view that Community Psychology has adopted. We can embrace all the various perspectives in Community Psychology without dismissing those who have a perspective different from our own, in what might be called a “big tent” (Toro, 2005). A belief in the value of “diversity” can apply to how we interact with our own colleagues in Community Psychology.

During this second decade, two new textbooks were published in 1977 by Heller and Monahan and Rappaport. Rappaport’s (1977) text, like his controversial Presidential address, presented a much more radical view of Community Psychology that emphasized the empowerment of the poor and otherwise disadvantaged, and a more active advocacy stance for community psychologists of the future.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was significant growth in the field of Community Psychology outside of the US and Canada. This growth included the first courses taught in Latin America (at the University of Puerto Rico; see Montero) and in Australia (see Fisher), where the first professional organization of community psychologists outside of North America occurred in 1983. Since this time, some of the greatest growth in formal membership has occurred in Community Psychology organizations in areas of the world outside of North America (Toro, 2005).

In 1987, James Kelly edited a special issue of the American Journal of Community Psychology to commemorate the field which had just turned 20 years old (Kelly, 1987). Some of the 12 articles in the issue were brief reminiscences, while others were more substantive. Beth Shinn, for example, urged community psychologists to enter an even wider range of domains, including schools, work sites, religious organizations, voluntary associations, and government. Annette Rickel made an analogy to Erikson’s developmental stages in reviewing the status of our field at the time. She suggested that Community Psychology had progressed through adolescence and was entering early adulthood. Extending this analogy, the field is now over 50 years old, well into “middle age.” And, consistent with the sorts of issues that Erikson suggested might crop up during middle-age, perhaps our field is concerned about its “long-term legacy.”

The “dueling addresses” mentioned above continued into the third decade. Annette Rickel in her 1986 Presidential address emphasized prevention, much like Cowen did in his address almost 10 years earlier. Beth Shinn in her 1992 Presidential address urged community psychologists to engage in new ways to cope with the social problem of homelessness. Irma Serrano-Garcia, based at the University of Puerto Rico, emphasized the need to empower the disenfranchised in her 1993 Presidential address. During this third decade, another new Community Psychology textbook was published (Levine & Perkins, 1987).

In 1988, there was a major conference in Chicago, IL trying to better define the theories and methods used by community psychologists (Tolan, Keys, Chertok, & Jason, 1990). Those in attendance discussed the role of theory in Community Psychology research. There was also an extended examination of the central and thorny methodological issue of taking into account the ecological levels of analysis. Also addressed were issues of implementing their research, which for community psychologists is a matter of actualizing their values in working collaboratively with community partners.

Starting in 1995, Sam Tsemberis (1999), a community psychologist from New York City, developed a program that has come to be called “Housing First.” The program, described in Chapter 1 (Jason, Glantsman, O’Brien, & Ramian, 2019), targets persons who are both homeless and seriously mentally ill. The intervention is a reaction to poorly researched transitional housing models that have rapidly become common in the US. Housing First combines up-front permanent housing with ongoing support services. In a few randomized trials, Housing First clients have become stably housed significantly quicker, and remained housed for significantly longer, than those in the control groups. Positive results have also recently been obtained in an evaluation of Housing First across five Canadian cities (Aubry et al., 2016). Housing first has also become very popular in Europe and in other developed nations. For the past three years, there has been an annual international conference to continue this work (see Tsemberis, 2018).

More attention during this decade was provided to one of the key themes of the field: participatory approaches to research, which are characterized by the active participation of community members in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of research. Greater knowledge of this approach was essential for developing ways to collaborate with community members in order to define and intervene with the numerous social problems they faced. Due to this need, the 2nd Chicago Conference on Community Research was hosted at Loyola University in Chicago in June of 2002 (Jason et al., 2004), and it focused on the refinement of the theories and methodologies that can guide participatory research.

In 2004, SCRA, the main professional organization promoting Community Psychology in North America, gained solid financial security, perhaps for the first time in its history, by acquiring the American Journal of Community Psychology from its original owner, the international publisher Kluwer/Plenum.

As another sign of the international growth of Community Psychology, in 2005 the European Community Psychology Association was formed. Prior to this development, Europeans had for many years a more informal “Network for Community Psychology.” The European Community Psychology Association has been operating an annual conference, held in different cities throughout Europe. As yet another sign of international growth, the first “International Conference on Community Psychology” was held in 2006 in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Held in even-numbered years, so as not to conflict with SCRA’s Biennial held in odd-numbered years, there have been International Conferences held in Portugal, Chile, Mexico, and South Africa. This international growth is very consistent with Community Psychology’s values emphasizing cultural diversity. Many community psychologists from around the world are actively collaborating with those in various nations around the world and an “internationalization” of the field is occurring in terms of practice, research, training, and theory (Reich, Riemer, Prilleltensky, & Montero, 2007).

In 2005, following the 40th anniversary of the founding of the field, a special issue on the history of Community Psychology was published in the Journal of Community Psychology (Fowler & Toro, 2008b). Articles in the special issue included a genealogical analysis of the influence of 10 key founders of the field (Fowler & Toro, 2008a), an account of “trailblazing” women in Community Psychology (Ayala-Alcantar et al., 2008), and documentation of the development of Community Psychology in different regions of the world (Latin America, see Montero and Australia, see Fisher).

Many community psychologists have made substantive contributions to the development of the field through their applied work, and have also impacted the development of the field through their teaching, mentorship, and conference presentations. Pokorny et al. (2009) tried to gauge the “influence” of community psychologists based on publications and citations to articles in the American Journal of Community Psychology and Journal of Community Psychology. Although many publications were by males from academic institutions, there were also publications from influential women, including Barbara Dohrenwend who contributed groundbreaking research dealing with a psychosocial stress model. She was also one of the original founders of the field of Community Psychology. Pokorny et al. did find that the number of women publishing articles has increased over time, as is evident in Case Study 2.2.

Case Study 2.2

Publications of Women in the Field

In 1970, around the time of the founding of the field of Community Psychology, women comprised approximately 20% of Ph.D. recipients in psychology. By 2005, nearly 72% of new psychology doctoral students were women. In many ways, articles published in journals are records of changing times as they illustrate how marginalized groups, like women, have transitioned to greater prominence. Patka, Jason, DiGangi, and Pokorny in 2010 found that in the early 1970s, women represented less than 12% of publishing authors in the two major Community Psychology journals, but by 2008, the number of women publishing in the two journals had increased to 61%. The findings from this study highlight the evolving role of women in the field of community psychology.

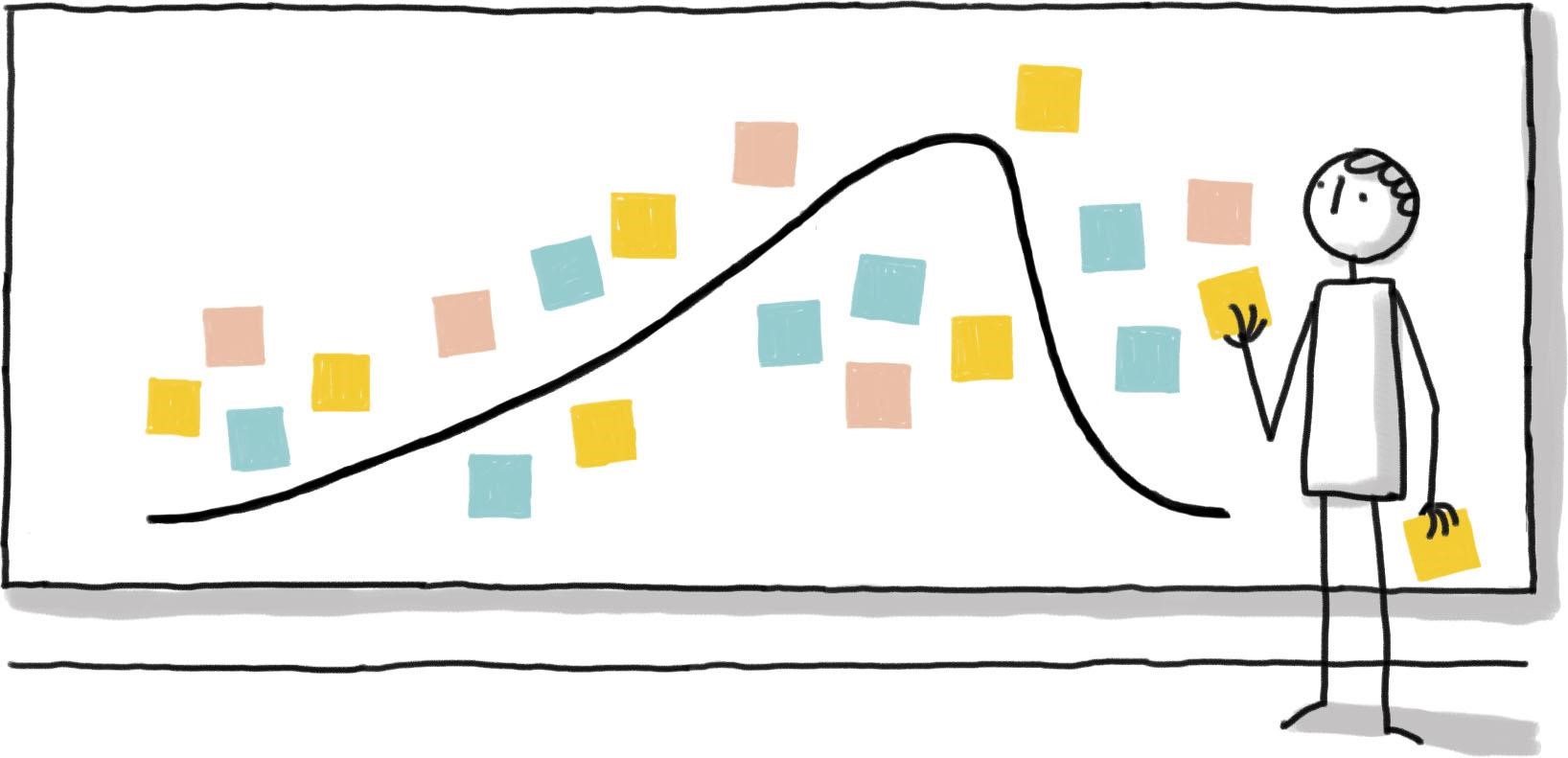

Community Psychology continued to make advances during this period in attempting to better understand social change in a world that is both complicated and often unpredictable. This field has increasingly worked to take into consideration dynamic feedback loops, which need to transcend simplistic linear cause and effect methods. In other words, the theories and methods of the field of Community Psychology are increasingly trying to capture a systems perspective, or the mutual interdependencies that Kelly’s ecological model has pointed to, regarding how people adapt to and become effective in diverse social environments.

New methods during the past 15 years have helped community psychologists conceptualize and empirically describe these dynamics, with quantitative and qualitative research methods that support contextually and theoretically-grounded community interventions (Jason & Glenwick, 2016). More attention is being directed to mixing qualitative and quantitative research methods in order to provide a deeper exploration of contextual factors. More sophisticated statistical methods help community psychologists address questions of importance as they work to describe the dynamics of complex systems that have the potential to transform our communities in fresh and innovative ways.

Finally, this free online textbook that you are reading, like the earlier development of the Ecological Community Psychology Conferences, is an illustration of how community psychologists put the field’s principles and theories into practice. Community psychologists believe that “giving psychology away” is the best course of action for an organization committed to prevention, social change, social justice, and empowerment. In addition, during the effort to assemble this online textbook, the editors worked with SCRA leadership to provide free SCRA Student Associate membership to undergraduates, which is another example of recent efforts to help lower barriers to participation in the field of Community Psychology.

This chapter has reviewed the last 50-plus years in which the field of Community Psychology has developed after its start in 1965 at the Swampscott Conference. With a focus on prevention, ecology and social justice, the field has offered society new ways of thinking about how we might best solve our social and community problems. The chapter has documented key events that have occurred, including organization changes, key publications and conferences, and international developments. The field has had some “growing pains,” but now appears to be well-established and mature.

Critical Thought Questions

Take the Chapter 2 Quiz

View the Chapter 2 Lecture Slides

____________________________________________________________________

Aubry, T., Goering, P., Veldhuizen, S., Adair, C. E., Bourque, J., Distasio, J., . . . Tsemberis, S. (2016). A multiple-city RCT of Housing First with Assertive Community Treatment for homeless Canadians with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 67(3), 275-281.

Ayala-Alcantar, C., Dello Stritto, E., & Guzman, B. L. (2008). Women in community psychology: The trailblazer story. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 587-608.

Bennett, C. C., Anderson, L. S., Cooper, S., Hassol, L., Klein, D. C., & Rosenblum, G. (1966). Community psychology: A report of the Boston Conference on the Education of Psychologists for Community Mental Health. Boston: Boston University Press.

Bloom, B. L. (1975). Community mental health: A general introduction. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Cowen, E. L., Trost, M. A., Izzo, L. D., Lorion, R. P., Dorr, D., & Isaacson, R. V. (1975). New ways in school mental health: Early detection and prevention of school maladaptation. New York: Human Sciences Press.

Fairweather, G. W., Sanders, D. H., Maynard, H., & Cressler, D. L. (1969). Community life for the mentally ill. Chicago: Aldine.

Fowler, P. J., & Toro, P. A. (2008a). Personal lineages and the development of community psychology: 1965 to 2005. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 626-648.

Fowler, P. J., & Toro, P. A. (2008b). The many histories of community psychology: Analyses of current trends and future prospects. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 569-571.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. Retrieved from https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro- to- community-psychology/

Jason, L. A. & Glenwick, D. S. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jason, L. A., Keys, C. B., Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Taylor, R. R., Davis, M., Durlak, J., Isenberg, D. (Eds.) (2004). Participatory Community Research: Theories and methods in action. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Kelly, J. G. (1966). Ecological constraints on mental health services. American Psychologist, 21, 535-539.

Kelly, J. G. (1987). Swampscott anniversary symposium: Reflections and recommendations on the 20th anniversary of Swampscott. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15(5).

Kloos, B., Hill, J., Thomas, E., Wandersman, A., Elias, M. J., & Dalton, J. H. (2012). Community psychology: Linking individuals and communities. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Levine, M., & Perkins, D. V. (1987). Principles of Community Psychology: Perspectives and applications. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moritsugu, J., Duffy, K., Vera, E., & Wong, F. (2019). Community Psychology (6th ed). New York: Routledge.

Pokorny, S. B., Adams, M., Jason, L. A., Patka, M., Cowman, S., & Topliff, A. (2009). Frequency and citations of published authors in two community psychology journals. Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 281-291.

Rappaport, J. (1977). Community psychology: Values, research, and action. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Reich, S., Riemer, M., Prilleltensky, I., Montero, M. (Eds.). (2007). International Community Psychology. History and theories. New York, NY: Springer.

Tolan, P., Keys, C., Chertok, F., & Jason, L. A. (Eds.). (1990). Researching Community Psychology: Issues of theories and methods. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Toro, P. A. (2005). Community psychology: Where do we go from here? American Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 9-16.

Tsemberis, S. (1999). From streets to homes: An innovative approach to supported housing for homeless adults with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 225-241.

Tsemberis, S. (June, 2018). Housing First: Why person centered care matters? Third International Housing First Conference, Padua, Italy.

Chapter Three Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

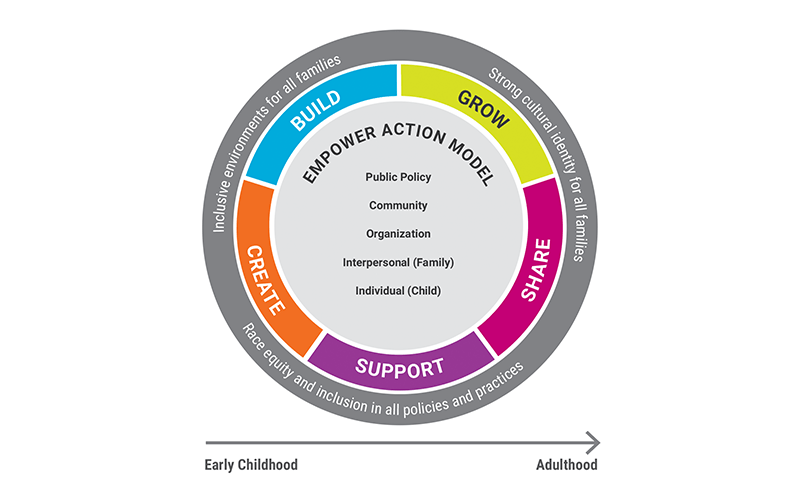

Community psychologists seek to improve community well-being through a cycle of collaborative planning, action, and research in partnership with local community members. As indicated in the first chapter (Jason, Glantsman, O’Brien, & Ramian, 2019), we emphasize exploring issues with a systems lens approach, and focus on prevention and community contexts of behavior. Community psychologists embrace the core values of the field which include 1) individual and family wellness, 2) sense of community, 3) respect for human diversity, 4) social justice, 5) empowerment and citizen participation, 6) collaboration and community strengths, and 7) empirical grounding.

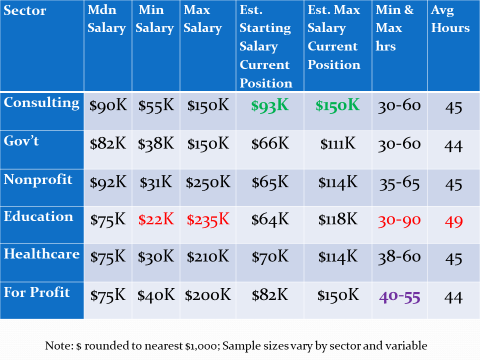

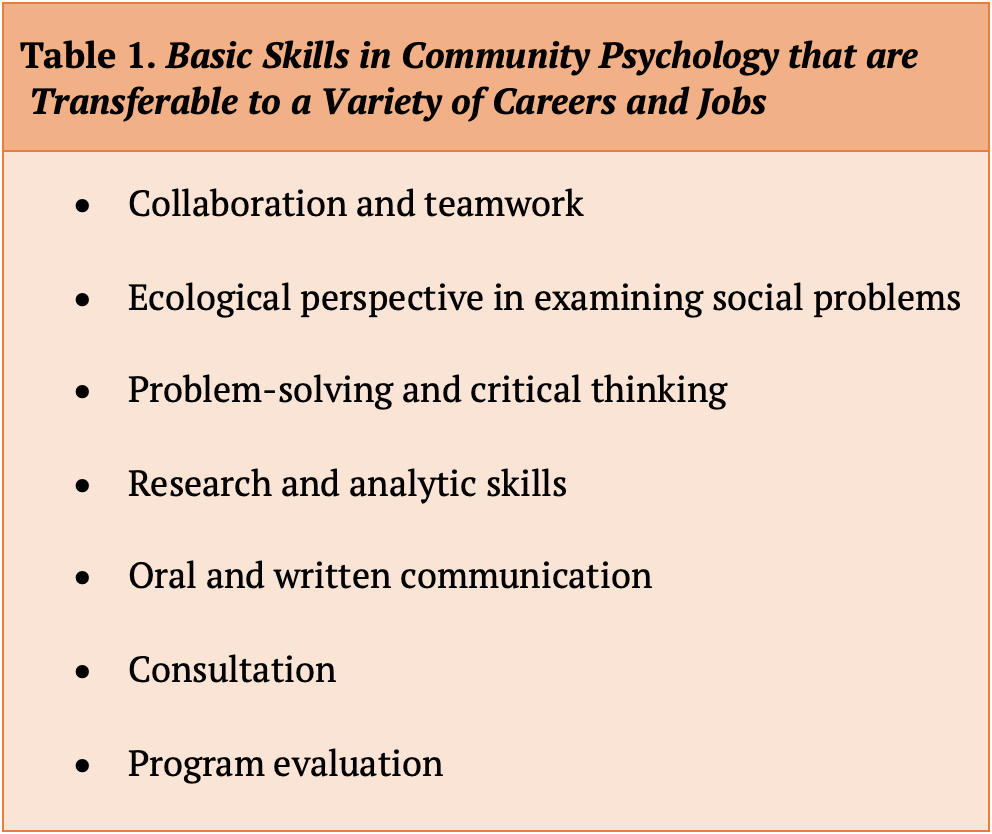

The settings of community psychologists range from academia to non-profit organization. Typically, community psychologists complete graduate work in the field, but that is not required to engage in community work. The work of a community psychologist is dependent on an individual’s interest, training, and experience. Community psychologists can work as researchers, policy developers, educators, program evaluators, or program coordinators within academic, government and non-profit settings (SCRA, 2018). These are not the only roles and settings of community psychologists and within this chapter, we will explore a diversity of career paths and employment options. All community psychologists have a passion for a specific community need or topic. What community issues are you most excited about addressing?

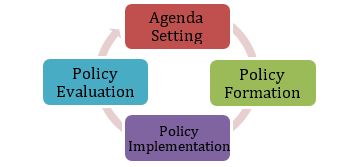

Community Psychology practice typically refers to applied or practical work of community psychologists, which can involve a variety of activities related to a cycle of action and research such as community organizing, coalition building, program development or program evaluation, policy, advocacy, grant writing, data collection, data analysis, or report writing. Community Psychology practice occurs in many community settings outside of the classroom or research center such as schools, community-based non-profit organizations, places of worship, health clinics, parks, community centers, or other neighborhood gathering spaces.

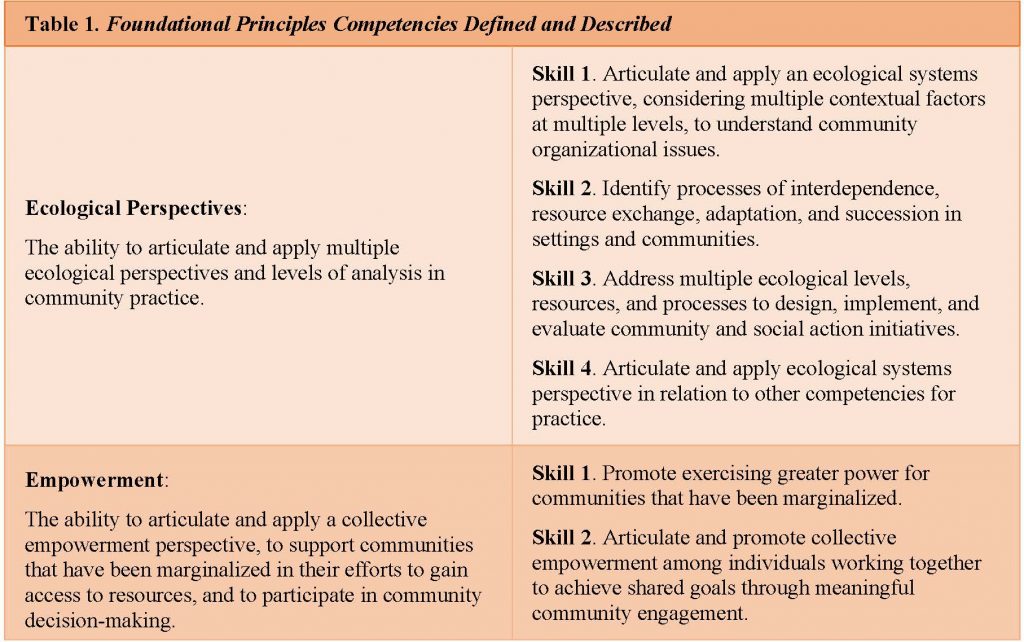

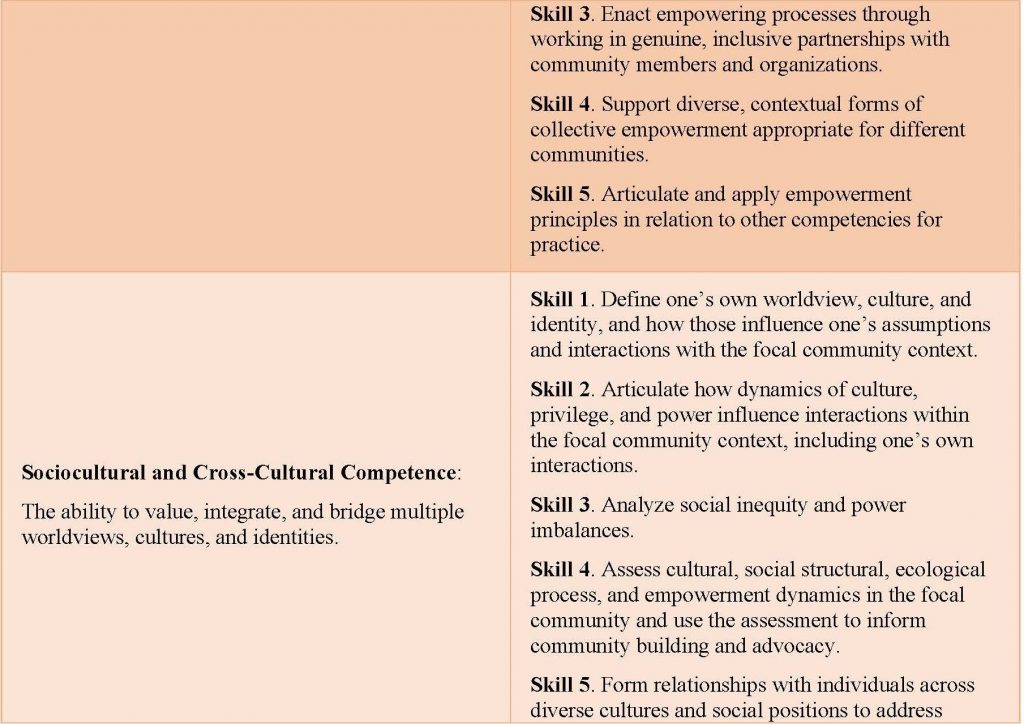

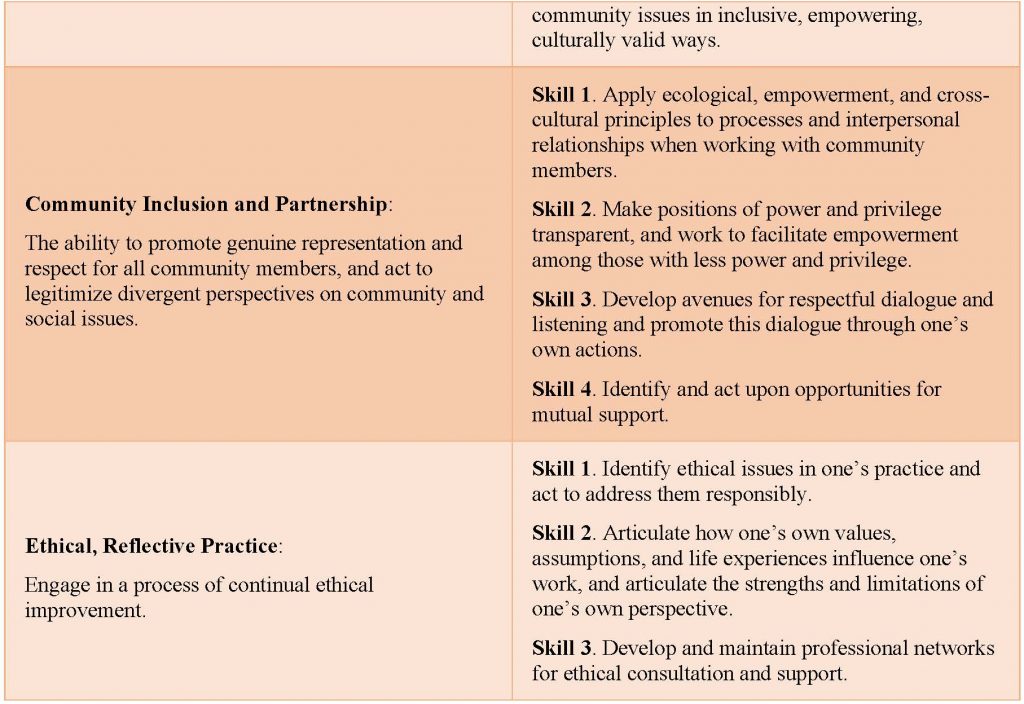

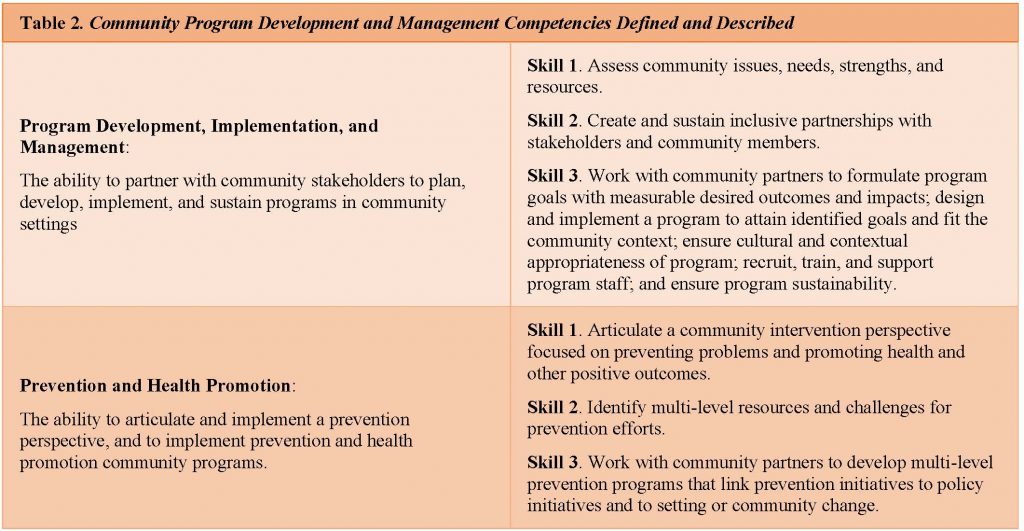

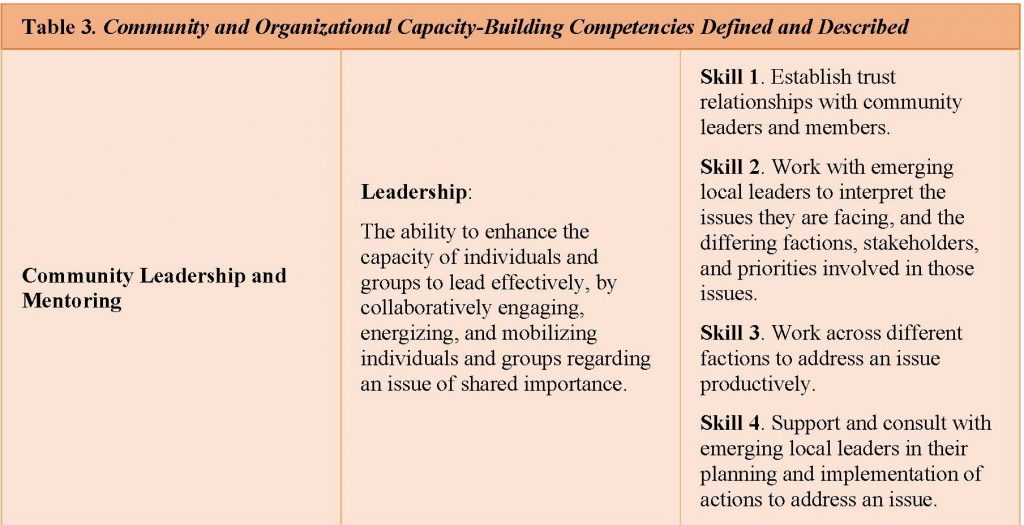

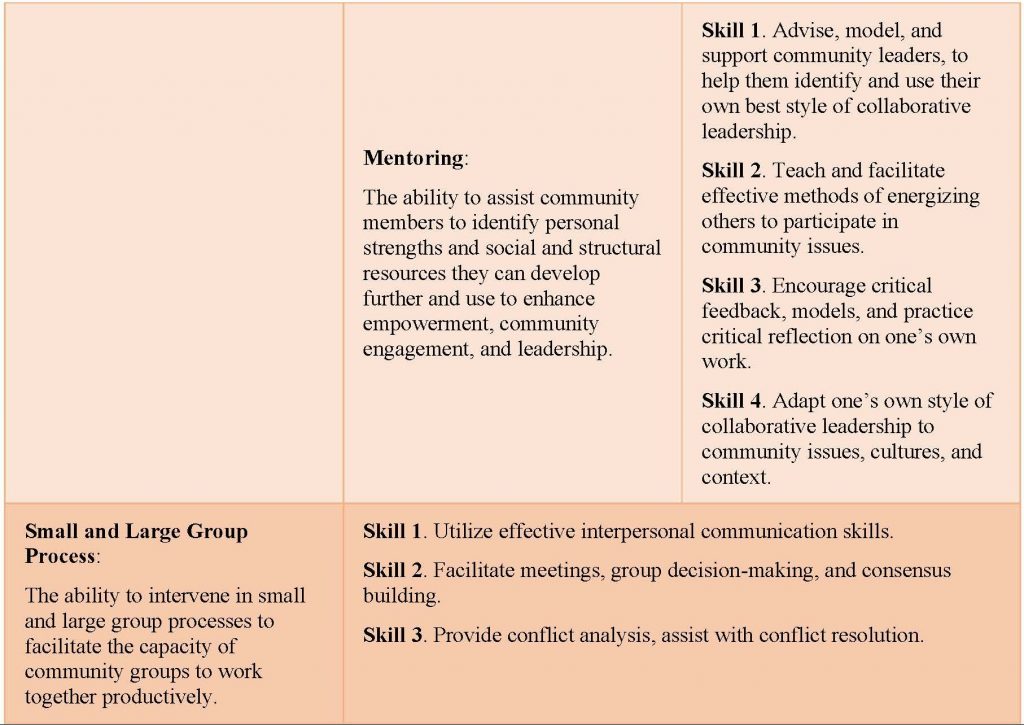

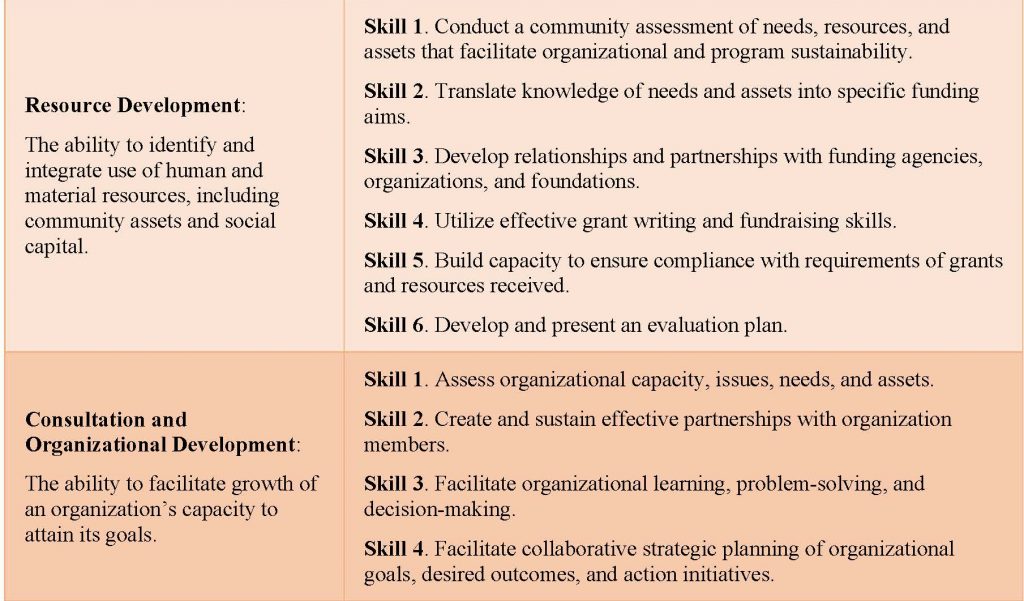

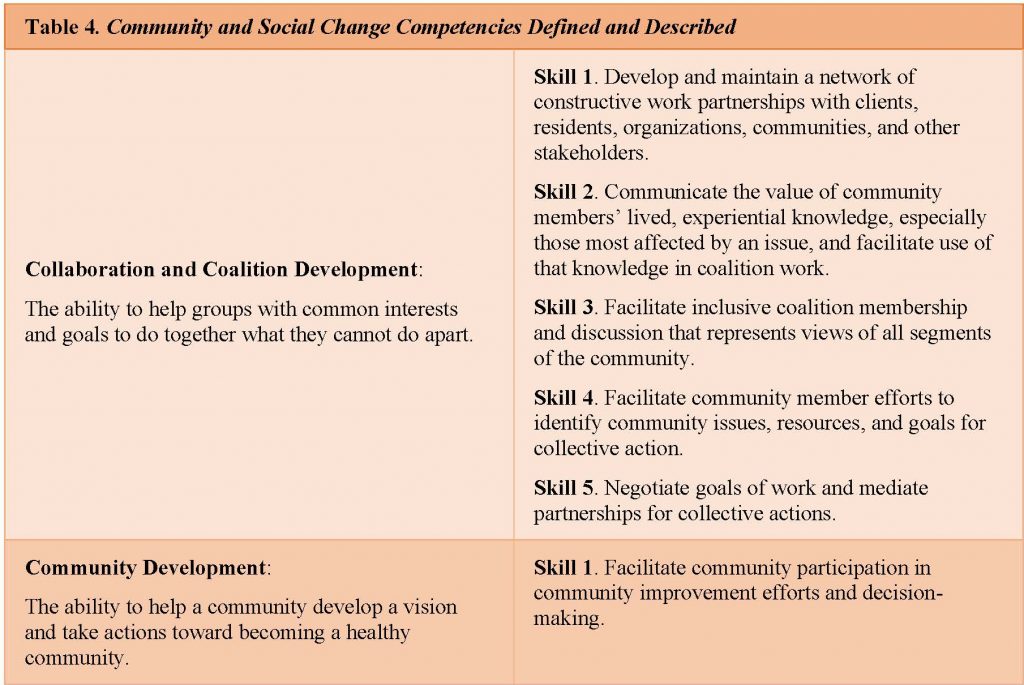

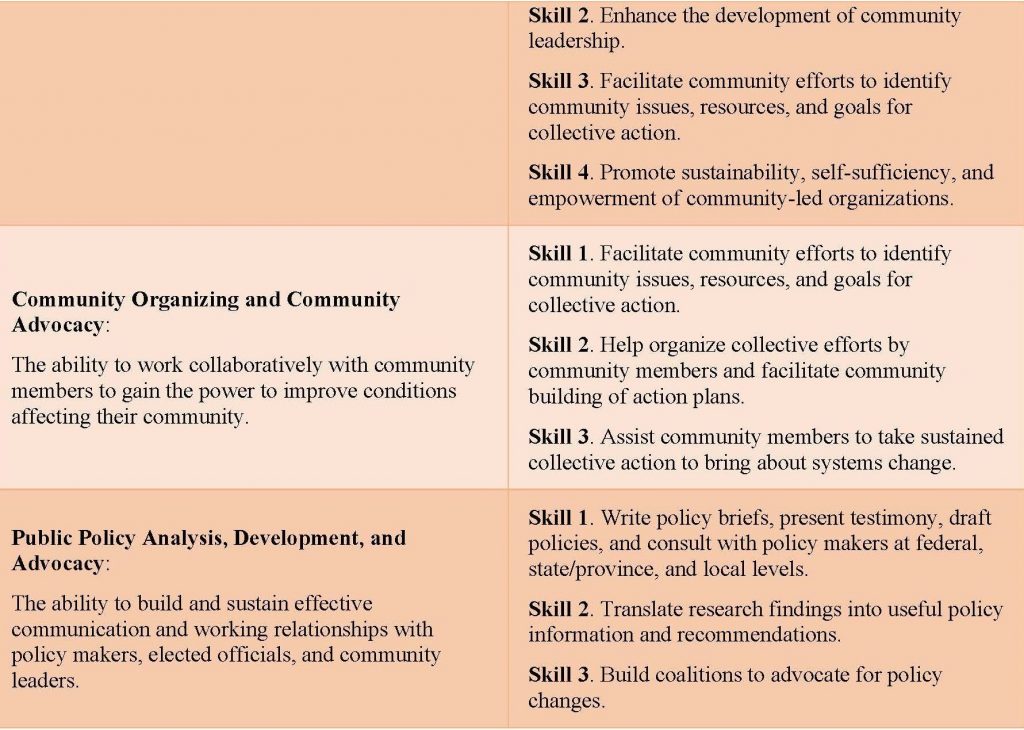

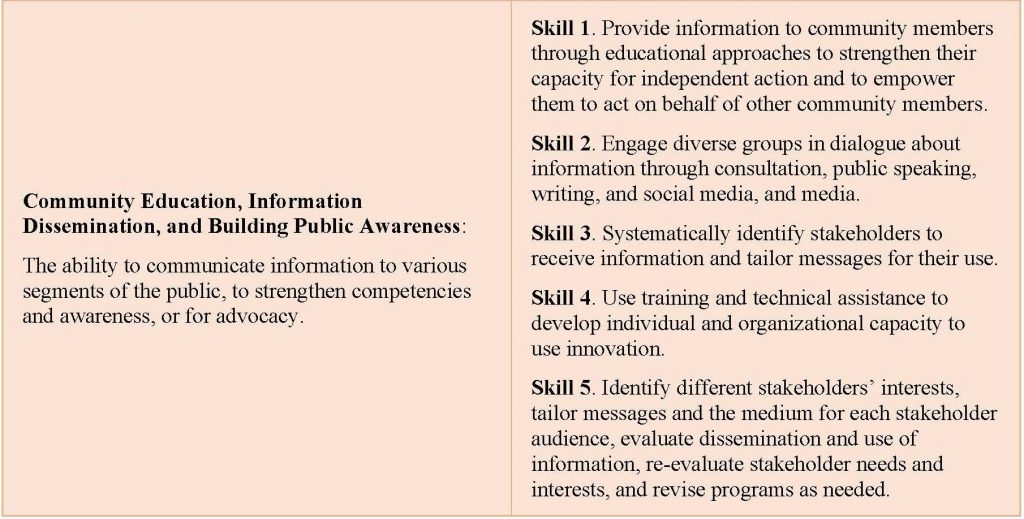

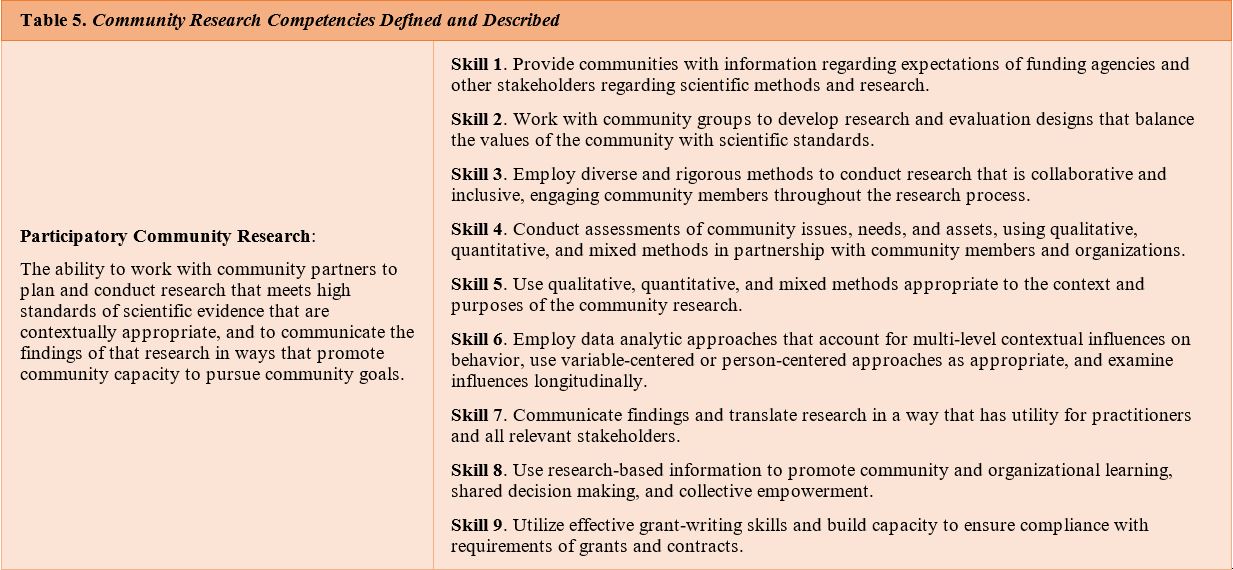

Due to the diversity of activities and settings for Community Psychology practice and its focus on systems, context, programs, and organizations as opposed to individuals, the field has decided not to have their members receive a license to practice. Rather, members of SCRA have developed competencies for Community Psychology practice to “…provide a common framework for the discussion of skills involved in Community Psychology practice, and how those skills can be learned” (SCRA, 2012, p. 9). The 18 competencies help define and clarify the unique combination of skills and values that differentiate community psychologists from other people working in community settings. They fall into five categories: 1) foundational principles, 2) community program development and management, 3) community organizational capacity building, 4) community and social change, and 5) community research. See the chapter by Wolfe (2019) to view a complete list of the competencies by category. To learn more about the competencies in Community Psychology check out Dalton and Wolfe (2012) and Wolfe and Price (2017).

If you want to dig even further into how a specific competency is used in work settings, see Elias, Neigher, and Johnson-Hakim (2015) which provides case examples of how each competency is enacted in practice. See Scott and Wolfe’s Community Psychology: Foundations for Practice (2015) which provides case examples of how each competency is enacted in practice. In addition, the Community Tool Box has an Ask An Advisor Tool which provides more examples of how to apply the competencies in different settings. Note that some Community Psychology scholars have raised concerns about the potential limiting aspects of focusing on competencies or provided counterpoints for their value (e.g., Dzidic, Breen, & Bishop, 2013). There are also some additional models or ways to categorize the skills of a community psychologist such as the one by Arcidiacono (2017), who describes the TRIP model (which stands for Trustfulness, Reflexivity, Intersectionality, and Positionality) as the core methodological skills acquired by community psychologists in their training as well as their basic values.

Practical Application 3.1 below can help you start the process of examining your current skills, the skills you want to acquire, and how you can find a career in Community Psychology that’s right for you.

Practical Application 3.1

Your Personal Fit with Community Psychology

Think of the competencies as a set of tools in a toolbox. You can pick and choose which competency to apply in various settings. In specific settings, some competencies are used more than others. Are there skills that are you are interested in gaining that you do not currently have? How can you build your skill set? This activity will help you start thinking about which skills you can build upon throughout your career.