This glossary is a summary of all key terms that appear at the end of each chapter.

Glossary

9/11 (ch 12): Has come to signify the terrorist attacks on multiple targets in the United States on 9 September 2001, and the beginning of the “War on Terror.”

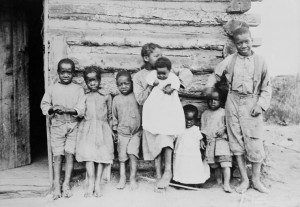

abolitionists (ch 3): Individuals and groups associated with the movement to end slavery in the United States. In Canada, abolitionists assisted African-Americans fleeing the United States, whether they were slaves or otherwise. The abolitionist movement built the foundation for subsequent social movements in Canada.

Aboriginal rights (ch 11): Defined in two ways: 1) as an abstract set of inherent and collective rights available on principle only to Aboriginal peoples, which may include land, resource and treaty rights; 2) also or alternately, cultural rights associated with traditional or customary practices which are thought to predate European contact. The latter are protected in the Constitution Act, 1982.

Aboriginal tourism (ch 11): Usually associated with cultural displays and/or performances, sometimes with Aboriginal lifestyle experiences. The sector was very small in the 1990s, but since has become an annual multi-million dollar industry.

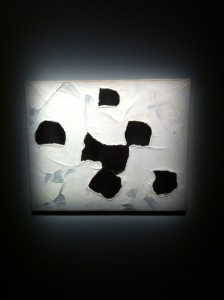

abstract (ch 10): An artistic technique that makes use of images that are not clearly representative of conventional visual references.

academic freedom (ch 9): The privilege and responsibility on the part of scholars to conduct enquiry and communicate findings free of sanction by external authorities.

Act of Union (ch 1): The third Canadian constitution since the Conquest in 1763. The Act of Union contained measures for the management of French-Canadians, built on the premise (from Lord Durham’s 1839 Report on the Affairs of British North America) that assimilation of French-Canadians was essential to the future of the larger colony.

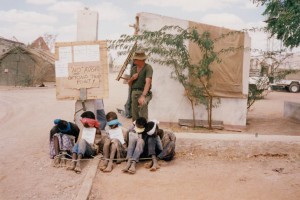

Afghanistan War (ch 12): Following 9/11, an alliance of forces including Canada which initiated a military campaign against the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001. Troop withdrawals from active duty were complete in 2014.

Agent Orange (ch 9): A herbicidal defoliant, used by the United States Army to destroy jungle cover in the Vietnam War.

Aird Commission (ch 10): The Royal Commission on Radio Broadcasting, 1922 to 1932; recommended the creation of what became the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

Alaska Highway (ch 9): A highway built during WWII to facilitate the movement of troops and materiel from the United States to its northern territory (not yet a state), Alaska. It was constructed between Dawson Creek, BC, and Delta Junction, Alaska, and completed in 1942. It served to open the Yukon to greater traffic and activity.

allophone (ch 5): A person whose first language is neither French nor English.

al-Qaeda (ch 12): A jihadist group pieced together in the 1980s by Americans to fight against the Soviet Union.

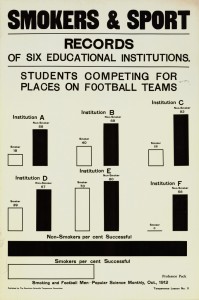

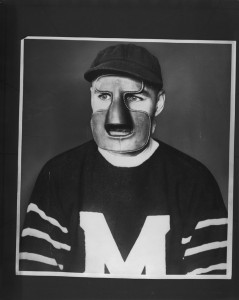

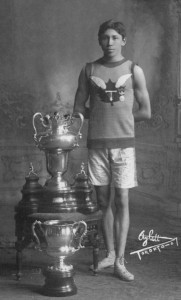

amateur (ch 10): In the context of the history of modern sport, refers to athletes who do not accept pay to play; also implies a middle- and upper-middle class ethos of fairplay and a hostility toward professionalism.

American Federation of Labor (AFL) (ch 3): Established in 1886 as an umbrella organization of craft unions in the United States.

American Indian Movement (AIM) (ch 9): Founded in 1968, an advocacy group established to counter the United States government’s Indian Termination policies of the 1950s and 1960s. Inspired by the civil rights movement it was influential among Canadian First Nations activists.

anarchist (ch 5): An individual who advocates the dismantling of the state and the creation of a structure based on voluntary association and participation.

anticlerical, anticlericalism (ch 4): Someone who believes that the separation of church and state in civic life is essential for the well-being of a successful democratic society.

antimodernism (ch 5): A retreat from modernization and modernity, often associated with rural and traditional values, spirituality, and social hierarchies.

anti-party (ch 7): The position that political parties constitute an unwelcome constraint on democratic politics.

apartheid (ch 9): A political and social system predicated on racial discrimination and/or segregation; associated with the Republic of South Africa from 1948 to 1994.

appeasement (ch 6): Refers to Britain’s policy of avoiding war with Germany by making concessions.

art deco (ch 6): A visual and decorative style associated with the first three decades of the 20th century and, in its emphasis on symmetry and its association with technological advancement, is often regarded as the foremost modernist style.

Arts and Crafts (ch 10): The Arts and Crafts Movement was an anti-industrial and antimodernist decorative tradition that looked to older hand-built styles of craftsmanship in visual arts, furniture, and domestic architecture.

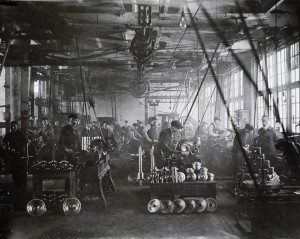

assembly line (ch 10): Refers to manufacturing processes that are systematically organized; most often associated in the public mind with the building of automobiles.

Assembly of First Nations (AFN) (ch 11): The successor to the National Indian Brotherhood (NIB), the AFN, a national advocacy organization that represents Aboriginal peoples, was established in 1982.

asymmetrical federalism (ch 9): A federation in which one or more constituent parts enjoys more autonomy and/or authority than one or more of the other constituent parts. In the case of the Meech Lake Accord, it was suggested that recognition of Quebec as a distinct society would create an asymmetry in confederation.

automation (ch 3): A manufacturing process in which assembly or some other part of the production system is performed by machines that are subject to control systems.

Auto Pact (ch 8): The Canada-US Automotive Products Agreement was signed in 1965. It removed tariffs on vehicles and automotive parts traded between Canada and the United States, creating a much more dynamic Canadian automobile sector and improving the trade deficit in the sector.

Avro Arrow (ch 9): An interceptor jet aircraft designed and built by A.V.Roe (Avro) Canada in the 1950s, capable of Mach 1.98. Production of the Arrow was stopped in what remains, in the mind of many Canadians, a controversial political decision.

back-to-the-land (ch 5): Refers to any of several anti-urban agrarian movements in which city dwellers are encouraged to return to simpler, pre-modern ways of living.

balance of power (ch 6): In international relations, refers to a complex of evenly weighted alliances that theoretically prohibit any one participant or side from going to war.

balance of power (ch 7): IIn parliamentary politics, describes a minority government that is dependent on another party to provide enough votes to prohibit defeat through a vote of non-confidence.

Balfour Declaration (ch 6): In 1926, a statement released at the Imperial Conference and named for the conference chair, Lord Balfour. Formally recognizes the Dominions of the British Empire as autonomous nations capable of independent action internationally and in the workings of the new British Commonwealth of Nations.

band offices (ch 11): The administrative centre of a First Nation band; a unit of government within the First Nation; applies principally to populations covered by the Indian Act (that is, Status Indians). The band council is the decision making assembly in the band office.

Bank of Canada (ch 8): Canada’s central bank, introduced by R. B. Bennett, January 1935, as part of a federal government economic intervention.

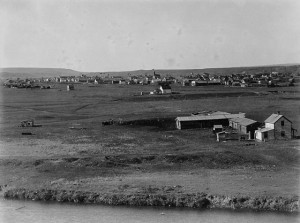

Barr Colony (ch 5): Located west of Saskatoon covering a massive area that extended to and across what would become the Saskatchewan-Alberta border, the colony was populated by some 2,000 immigrants recruited directly from Britain.

Battle of Ballantyne Pier (ch 8): 18 June 1935; a violent confrontation between striking Vancouver dockyard workers and a force made up of city police, provincial police, and RCMP.

Battle of Britain (ch 6): A series of aerial attacks launched by Germany against Britain beginning in July 1940 and countered by an aerial defence. Along with the strategic night bombing campaign that followed (the Blitz), it can be said to have lasted for nearly one year.

Battle of the Atlantic (ch 6): A nearly continuous series of naval confrontations that began in 1939 and ended only with the fall of Germany in 1945.

Bay Street (ch 9): In Toronto, the location of Canada’s leading financial offices, banks, and corporations, as well as the Toronto Stock Exchange.

Beaver Hall Group (ch 10): A group of nearly two dozen painters based in Montreal whose modernist and urban style was at odds with the Group of Seven’s wilderness and nationalist abstractions.

bedroom communities (ch 9): Suburbs to which commuters return at the end of the day to do little other than sleep before commuting out to jobs elsewhere; applies especially to those suburbs that are largely free of industry and other sources of employment.

Beothuk (ch 2): Aboriginal people of Newfoundland; believed to have disappeared — due to exotic diseases, loss of territory, and armed conflict with European colonists — by the second quarter of the 19th century.

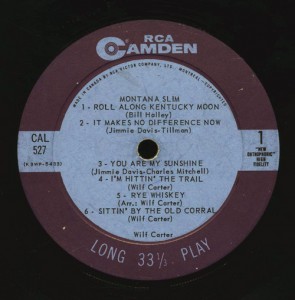

big band (ch 9): A musical group involving as many as two dozen players; associated with jazz and swing music from the interwar and early post-WWII years.

Big Data (ch 12): Refers to collections of enormous data sets that typically include large quantities of demographic information useful in social analysis.

big science (ch 10): Associated with the large scale experiments and processes that became possible after the Second World War.

Bill 101 (ch 9): The Charter of the French Language, passed into law in 1977 which advanced the provisions of the Official Language Act (Bill 22) of 1974, and which made French Quebec’s official language. Bill 101 established the primacy of French in day to day life.

Bill 178 (ch 9): One of several amendments to the Charter of the French Language (see Bill 101); introduced and proclaimed in December 1988 in response to a Supreme Court ruling that would end the unilingual French signage provisions of the Charter. It is significant for its reference to the “notwithstanding clause” of the federal Charter of Rights.

bipolar (ch 12): The essence of the Cold War in that there were two superpowers in existence. Juxtaposed with the unipolar world at the end of the Cold War.

birth control (ch 9): Any method or practice aimed at reducing fertility or preventing the complete gestation of an infant; may include abstinence, the use of chemicals/drugs, termination, and prophylactics.

blacklist (ch 3): Sanctions taken by employers against workers whom they associate with labour organization, strikes, certain ideological movements, or other actions contrary to the employers’ interests. Technically, a list of individuals who were denied work on the basis of their involvement in pro-labour activities.

Blacklist (ch 9): A list of people suspected of having Communist sympathies who were denied work as a result.

Black Tuesday (ch 8): 24 October 1929 (a Tuesday) was the day the New York Stock Exchange crashed, beginning the decade-long Great Depression.

block settlements (ch 5): An initiative in settling the West with groups drawn from the same ethnicity or creed allocated contiguous lands so as to take advantage of cultures of mutual support.

Bloody Saturday (ch 3): 21 June 1919; during a mass demonstration of solidarity (after ten OBU leaders were arrested, including J. S. Woodsworth) in which a buildup of state resources (troops, Mounties and Specials) were brought in. 30 protesters were injured and two killed.

Bloody Sunday (ch 8): Sunday at daybreak, 19 June 1938, while the Vancouver Police peacefully evacuated the Art Gallery (occupied by unemployed protesters); the RCMP stormed the Post Office with tear gas and truncheons. A window-smashing campaign followed and, hours later, a demonstration of support took place at an East End park where 10-15,000 locals gathered. Many were hospitalized that day.

Bolshevik (ch 3): A workers’ party that led the Russian Revolution in October 1917 under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin.

boondoggles (ch 8): Meaningless routine work, associated with “work relief” for the unemployed, intended to keep them busy but not necessarily productive.

boosters (ch 3): Civic promoters.

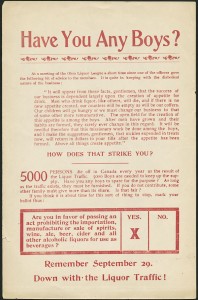

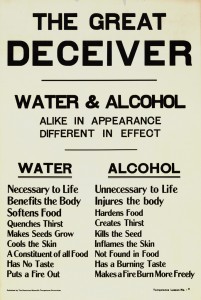

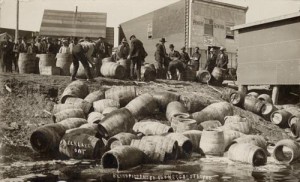

bootlegging (ch 5): Unlicensed, typically illegal production of alcohol. Also, in some instances, the sale of the same or of other illicit goods.

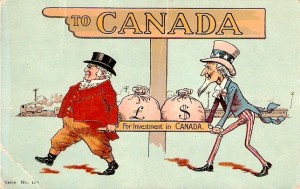

branch plants (ch 4): Typically American-owned companies that avoided tariff barriers by establishing plants on the Canadian side of the border.

Bretton Woods (ch 8): Established in July 1944, a system of institutions, principles, and processes by which the international monetary system could be managed. The Bretton Woods system lasted until 1971, when the United States ended the convertibility of the dollar to gold.

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) (ch 10): Established in 1922, the BBC is a crown-owned public service broadcaster. Its equivalent in Canada is the CBC.

British Commonwealth of Nations (ch 6): A voluntary association of Britain and its former colonies. Established incrementally after 1919 and especially in the Balfour Declaration (1926).

British Invasion (ch 9): A surge of popularity enjoyed in North America by British musicians, artists, writers, and film makers in the 1960s.

brownfield projects (ch 8): Civic projects that re-purpose (sometimes at enormous cost) or rehabilitate industrial spaces for post-industrial use.

Burnt Church Crisis (ch 11): Between 1999 and 2002, a confrontation between the Burnt Church First Nation (a Mi’kmaq community in New Brunswick) and non-Aboriginal fishers and the Federal Department of Fisheries.

business unions (ch 3): Trade or craft unions that approach activism from a non-revolutionary position; associated with the unions of the AFL, the TLC, and — later — the CLC.

Calder Case (ch 11): Supreme Court case (Calder v British Columbia) in 1973 that decided that Aboriginal title existed prior to colonization and persisted after 1871.

Calgary Declaration (ch 12): Also called the Calgary Accord; in 1997, an agreement signed between all provinces but Quebec; established principles for future constitutional change while enshrining principles regarding equality of rights, inclusion, and multiculturalism.

Canada Act (1982) (ch 9): Federal legislation that enabled the patriation of the Canadian constitution and the possibility of its amendment in Canada, rather than in Britain.

Canada First (ch 4): Established in 1868, an English-Canadian nationalist movement.

Canada Pension Plan (CPP) (ch 9): Introduced by the federal government in 1965; the first publicly funded pension plan in Canada; transfers earnings from working people to retired citizens.

Canada Student Loans (ch 9): Replaced the Dominion-Provincial Student Loan Program (1939-1964); guaranteed the banks’ risk in extending loans to post-secondary students under the auspices of the program.

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) (ch 10): In full, the CBC/Radio Canada. Public broadcasting system established in 1932 following the recommendations of the Aird Commission. Its status as a Crown Corporation was clarified under the Canadian Broadcasting Act (1936). Modelled in large measure on the BBC.

Canadian Caper (ch 9): The rescue of six American diplomats during the Iranian Revolution of 1979 to 1980.

Canadian content (CanCon) rules (ch 9): Under the authority of the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), CanCon regulations were established to ensure a quota of Canadian creative product in various media, particularly television and radio.

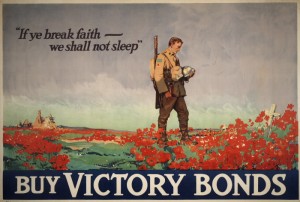

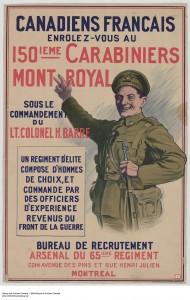

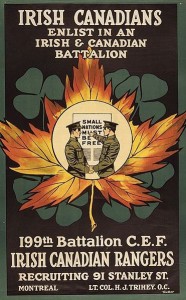

Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) (ch 6): The name given to the troops sent overseas during the Great War (World War I).

Canadian Football League (ch 10): Established in 1958 when Canadian-style rugby teams left the Canadian Rugby Union to establish a nine-team professional league.

Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) (ch 3): Founded in 1956 in a merger of the Trades and Labour Congress (TLC) and the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL). Subsequently joined with the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) to create the New Democratic Party (NDP).

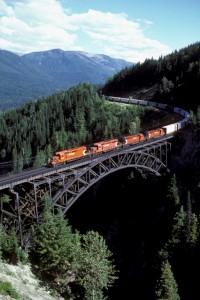

Canadian National Railway (ch 6): Created in 1919 out of several financially troubled railway companies that had been inherited by Ottawa, including the Canadian Northern Railway and the Grand Trunk Railway; constituted a trans-continental operation in competition with the CPR.

Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) (ch 9): An independent government agency established in 1968 to regulate and supervise all elements of the broadcasting systems.

Canadian Wheat Board (ch 8): Canada’s Marketing Board for wheat and barley was introduced by R. B. Bennett in July 1935 as part of a federal government economic intervention.

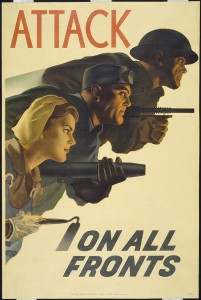

Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWACs) (ch 6): Established in 1941 as a separate non-combatant unit of the Canadian Army; provided support mainly as office staff, drivers/mechanics, and canteen workers; some served overseas.

capitalism, capitalists (ch 3): An economic system (and its practitioners) that is based on the ability of private individuals to accumulate and invest money (capital) in profit-making enterprises. Also, a system that is dominated by the private ownership of the means of production.

Capital markets (ch 8): A combination of institutions that enable the buying and selling of money through instruments like loans and securities.

Cariboo Wagon Road (ch 2): A pair of routes to the gold-bearing regions on the Interior Plateau of British Columbia, initiated in 1860. One begins in Fort Douglas, the other at Yale.

Carruthers Commission (ch 9): Established in 1963 and reported out in 1966; recommended a devolution of authority from Ottawa to the North West Territories; headquartered at Yellowknife.

CÉGEPs (ch 9): Publicly funded pre-university colleges in Quebec.

cellular (ch 8): A telecommunications system involving a wireless connection. Cellular telephones first became available to the public in the mid-1980s.

Centennial (ch 9): A 100th anniversary; in Canada, is used as shorthand to refer to the 1967 celebration of 100 years of Confederation.

Central Business District (ch 9): The concentration of commercial, business, and finance enterprises generally in the centre or downtown of most cities. Some cities, like Toronto, have several such hubs.

Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) (ch 9): Created under the National Housing Act, 1944; enabled low income families (including demobilized servicemen and women) to obtain low cost mortgages; created social housing; funded construction of new rental housing; and continues to function in 2016.

centrifugal federalism (ch 8): Federalism as a dynamic process of decentralization and recentralization, or centrifugal versus centripetal forces.

Charlottetown Accord (ch 12): 1992; a package of proposed constitutional changes; defeated in a national referendum.

Charter of Rights and Freedoms (ch 9): Also known simply as the Charter; incorporated by the British government in the Canada Act, 1982; comprises the first part of the Constitution Act, 1982.

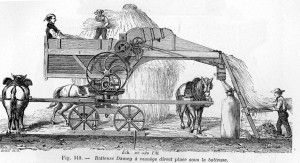

chilled steel plough (ch 3): A significant late 19th century advance in plough manufacturing. Stronger steel enabled the cutting of faster and deeper furrows and the breaking of densely packed prairie soil.

Chinatowns (ch 5): Colloquial term for enclaves of Chinese immigrants. In Canada and primarily in British Columbia, these appeared from 1858 on, with the greatest increase occurring during the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Created by external forces (Euro-Canadian civic authority limiting Chinese property ownership and business licenses to a small area) and internal needs (the concentration of Chinese financial and social institutions).

Chinese Benevolent Association (ch 5): An organization that coordinated the interests and politics of the various community organizations in Chinatowns, and provided different levels of social support for its members.

Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand (ch 3): During the Winnipeg General Strike, 1919, an organization established by the city’s business and political elites to break the strike and challenge the authority of the Strike Committee.

Civil Rights Movement (ch 9): In the United States, beginning in the mid-1950s, this was a movement to secure the rights promised in court decisions. Widespread protest, frequent violence, and growing support throughout the USA — much of which was televised — influenced Canadians who sought to address inequities in their own society.

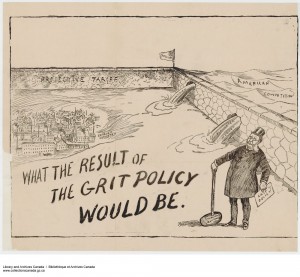

Clear Grit (ch 1): Reformers in Canada West (Ontario) before Confederation. Anti-Catholic and largely anti-French, the Grits opposed John A. Macdonald’s Tories and advocated the annexation of Rupert’s Land. In the post-Confederation period they became one section of the Liberal Party.

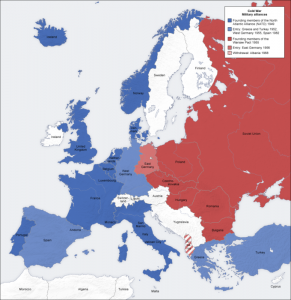

Cold War (ch 9): The prolonged period of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union, based on ideological conflicts and competition for military, economic, social, and technological superiority, and marked by surveillance and espionage, political assassinations, an arms race, attempts to secure alliances with developing nations, and proxy wars.

collective bargaining (ch 3): Negotiation of working conditions, pay, and other issues or benefits by an association — a “union” — of employees. Replaced the many individual arrangements made in one-on-one agreements.

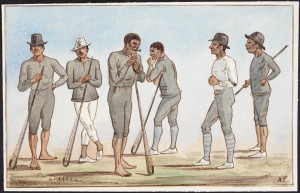

colour barriers (ch 10): Racial segregation; specifically, the exclusion of people of colour from activities or services enjoyed by Euro-Canadians.

command-led economy (ch 8): An economic order in which government is the principal buyer of goods produced, for itself or for distribution. See demand-led economy.

commercialization (ch 8): In late 20th century post-secondary education, the search for opportunities to develop revenue streams by taking new ideas to market.

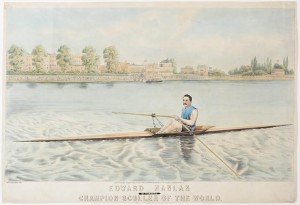

commodification (ch 10): In the context of the professionalization of sports and leisure, the process of turning what originally was an informal and voluntary set of practices into a commodity to be bought and sold.

company store (ch 3): An outlet owned by an employer, one that sells goods to employees of the same firm. Commonplace in company towns. See also company towns.

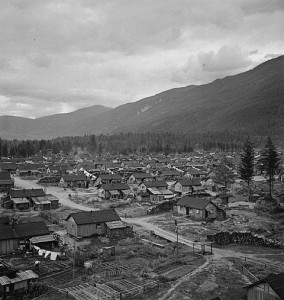

company towns (ch 3): A community with one major employer and few other employers; one in which most or all services — in some instances including housing and the supply of food — are controlled by the employer. Associated with remote resource extraction communities.

Comintern (ch 7): Also the Communist International, the Third International; 1919-1943; called for world revolution and the establishment of communist regimes.

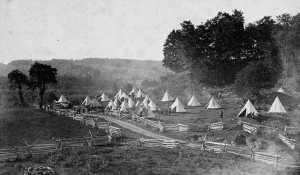

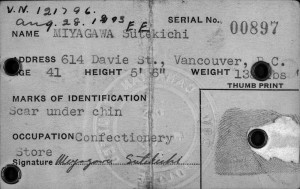

concentration camps (ch 6): A prison camp established to contain and punish captured populations. The British ran concentration camps for Boer prisoners in the Second Boer War; Canada placed suspected enemy aliens — Ukrainians and Germans in the Great War, Germans, Italians, and Japanese in the Second — in camps that were not punitive but nor were they appropriately provisioned; and the Germans infamously used concentration camps as the means of executing large numbers of Jewish prisoners (along with other “enemies” of the Reich). Concentration camps continue to be used.

Confederation League (ch 2): Founded by Amor de Cosmos and John Robson in 1868, promoting the idea of union with Canada through newspapers and direct lobbying of administrations in Victoria, Ottawa, and London. Their goals included responsible government in the colony, reciprocity with the United States, and austerity measures to address colonial debt.

confessional schools (ch 4): Religious schools run by Catholic or Protestant denominations.

consumer durables (ch 8): Products that last a long time and which consumers do not have to buy often; for example, cars, furniture, and appliances.

containment (ch 9): The American policy that sought to limit the expansion of Communism abroad.

Contemporary Arts Society (ch 10): Formed in 1939 in Montreal, lasted until the late 1940s; influential in its production and advocacy for modern art.

contemporary history (ch 12): The study of very recent history.

context group (ch 5): In a society comprised of some diversity, refers to the most influential group whose culture other groups seek to adopt or are obliged to assimilate into. See also, reference group.

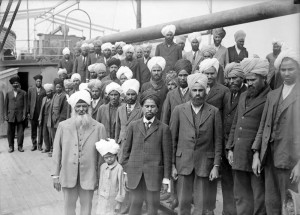

continuous voyage requirement (ch 5): Regulation passed by the federal government in 1908 to restrict immigration from India and Japan; required immigrants to reach Canada by means of a single, continuous, unbroken voyage. Would affect long journeys that necessitated a stop in either Japan or Hawaii. Tightened in 1914, leading to the challenge posed by the Komagata Maru.

cooperative movement (ch 7): Also spelled co-operative. Established in growing numbers in Britain in the mid-19th century and is associated with the “Rochdale Pioneers”; several typologies; goals include making available goods and/or supplies to members at low costs by taking advantage of economies of scale as a group, also obtaining optimal prices for community products by pooling output for sale. Surpluses and profits are redistributed to members of the cooperative; some have an educational mandate as well. Examples include grocery stores, housing co-ops, and the dairy industry. See also wheat pools.

Corn Laws (1794-1846) (ch 8): A result of population growth and an economic downturn at the end of the Napoleonic Wars; tariffs and restrictions were imposed on imported grain (to Britain), which increased prices in an attempt to give domestic producers an edge.

corporate welfarism (ch 3): Equates subsidies to corporations with social welfare paid to individuals. In 1972, NDP leader David Lewis coined the phrase “corporate welfare bums” as a way of identifying what he perceived as the hypocrisy of attacks on the poor by anti-welfare business leaders.

counter culture (ch 5): A challenge to mainstream culture posed by a group’s rejection of dominant values. In the 1960s youth movements and specifically the hippy movement constituted a counter cultural moment.

Court of Chancery (ch 7): In England, the Court dealt primarily with trusts; dissolved in 1875.

craft capitalism (ch 3): Refers to a transition to capitalism led by craftworkers.

creative economy (ch 8): In the late 20th century, the idea that the economy was shifting away from an industry-dominated model to one in which ideas and creativity would matter more.

Criminal Code (ch 11): Properly, an Act respecting the criminal law; the Criminal Code is a regularly amended body of legislation pertaining to criminal — as opposed to civil or statute — law.

crude birth rate (ch 9): The number of births occurring in a community or nation per 1,000 population.

cultural genocide (ch 11): Premeditated and systematic attempts to eliminate a culture while not necessarily exterminating the population.

cultural mosaic (ch 5): In contrast to the concept of a “melting pot,” refers to a multi-ethnic and multicultural society in which differences are permitted to continue, rather than face assimilation into a single typology.

declericalization (ch 9): A movement to replace church authority with state authority in the running of schools and other institutions.

deconstructing (ch 12): An examination of the relationship between text and meaning.

deindustrialization (ch 8): The process of moving away from an old-style industrial order, which typically involves the shuttering of declining industries.

Delgamuukw vs. British Columbia (ch 11): 1997 landmark decision in the Supreme Court of Canada; established a test for the existence of Aboriginal title, extended title beyond evidence of past use to include custodianship of territory, and thus includes a cultural relationship — rather than simply an economic relationship — with the land.

demand-led economy (ch 8): An economic order in which the free market dominates and in which industries and consumers are the principal buyers of goods, thereby determining what goods will be produced. See command-led economy.

demonstrations (or demos) (ch 9): Protest events; includes marches, sit-ins, and occupation of offices, as well as other forms.

Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (ch 11): Created in 1966, a successor administrative unit to the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA).

Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) (ch 11): Established in 1888 to administer the Federal Government’s responsibilities as regards First Nations; was housed for many years under the office of the Minister of the Interior (who was also responsible for settling the West with immigrants).

deskilling (ch 3): Mechanization and automation of work, as well as assembly lines permits the systematization of work and a commensurate reduction in the skills and training needed to perform key functions. The work is said to be deskilled and, thus, the workforce too is deskilled.

détente (ch 9): The relaxation of tensions and improvement of relations between the West and the East in the Cold War during the 1970s.

devolution (ch 9): This when a senior level of government hands some of its authority to a lower level or ostensibly lower level of administration. In Canada in the 1960s, authority over the North-West Territories devolved to the new administration in Yellowknife, NWT.

Dieppe Raid (ch 6): 19 August 1942; also known as “Operation Jubilee;” an attack on the north coast of France that was meant to gather intelligence for a larger subsequent invasion; of the 6,000 Allied troops involved, 5,000 were Canadian. The mission was badly planned, atrociously researched, and tragic in its execution. Nevertheless, it contributed intelligence that helped at Normandy three years later.

disallowance (ch 2): An effective veto held by Ottawa that could be used to overturn provincial legislation.

Displaced Persons (ch 5): Peoples (principally in Europe) dislocated by World War II; refugees.

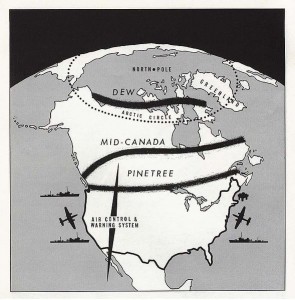

Distant Early Warning Line (ch 9): The northernmost of three Cold War radar systems aligned from west to east to identify incoming Soviet missiles in the event of an attack.

distinct society (ch 9): A term devised during the Quiet Revolution to describe Quebec vis-à-vis the rest of Canada; a “distinct society clause” was created that would recognize and enshrine that difference. In the Charlottetown Accord, this was spelled out as recognition of “a French speaking majority, a unique culture and a unique civil law tradition.”

dole (ch 8): Colloquial term for “relief” or welfare payments.

dollar-a-year men (ch 6): Leading entrepreneurs, financiers, and manufacturers on loan from their companies to the federal government for the duration of the Second World War for a nominal fee of one dollar.

Dominion Lands Act (ch 2): 1872; the legal mechanism that made possible the distribution of western lands.

domino theory (ch 9): The theory that if Communism made inroads in one nation, surrounding nations would also succumb one by one, like a chain of dominos toppling one another.

dot-com bubble (ch 8): A late 20th, early 21st century investment frenzy based on advances in Internet-based commerce that burst with the collapse of the market in 2000, crippling growth in the sector for several years.

Douglas Treaties (ch 11): Negotiated by Governor James Douglas of Vancouver Island in the colonial era and concluded with 14 First Nations in the colony in the early 1850s; apart from Treaty No.8 in the Peace District, the only treaties in British Columbia before the late 20th century.

Doukhobors (ch 5): An immigrant group comprised of pacifists belonging to a Russian dissident religious movement. Settled first on the Prairies then mostly relocated to British Columbia. Persecuted in the 20th century for their pacifism and their rejection of material culture.

dower laws (ch 3): Formal recognition of a widow’s lifetime interest in matrimonial property on the death of her husband. See also homestead rights.

draft dodgers (ch 9): Principally refers to American men who avoided mandatory, selective service in the Vietnam War by fleeing to Canada in the 1960s and 1970s.

dualism (ch 4): The idea that Canada could or should construct its culture and institutions around two cultures, French and English. In contrast with unification (which favours one culture) and pluralism or multiculturalism in which French in particular is at risk of becoming a minority culture.

Dunkirk (ch 6): Refers to the hurried evacuation of Canadian, British, and other troops from the port of the same name following their retreat in the face of Germany’s invasion of northern France in 1940.

Dust Bowl (ch 8): Describes the drought conditions that occurred across the prairies and plains of North America in the 1930s and the concurrent poverty associated with the economic depression.

Eastern Bloc (ch 9): The alliance of pro-Soviet (or USSR-dominated) countries in Eastern Europe in the post-WWII era, consisting of Poland, East Germany, Czecho-Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and, more loosely, Albania. Yugoslavia, another communist-dominated country, regularly declared itself separate from the Eastern Bloc; formalized in the mutual security agreement, the Warsaw Pact, 1955.

Eastern Group of Painters (ch 10): Established in Montreal in 1938.

equal rights (ch 3): In the context of feminism, the belief that rights accorded to men and women ought to be the same. Diverges somewhat from maternal feminism which claims rights based on gendered differences.

equalization (ch 8): Refers to programs and policies geared to redistribution of wealth between provinces to ensure a comparable level of services and quality of life in all parts of Canada.

escapist (ch 10): Typically refers to entertainments that divert one’s attention from banal features of everyday life.

Escheat Movement (ch 2): An organized movement in 19th century Prince Edward Island with the objective of ending absent landlordism and the distribution of lands to tenant farmers.

Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway (ch 2): 1871; the E&N was built to connect the coalfields of the central island with the British Columbia capital, Victoria.

essential industries (ch 3): Sectors identified in a crisis (such as wartime) as fundamental to the survival of the economy or society or war effort. Workers in those sectors are typically protected against conscription and may also be restricted in their ability to move to other jobs. In some instances, the state takes direct control of the industries for the duration of the crisis or longer.

established churches (ch 7): Organized religion recognized by the state. In Canada there are no officially recognized sects but the Anglican Church is the “established church” of England and the Queen is its head. Similarly, the Catholic Church was historically the official church of French Canada and it retains in the post-Confederation period a de facto official status.

establishment (ch 9): An elite, colloquially in the 1960s; the conventional social and economic order.

ethnic cleansing (ch 12): A variant on genocide in that it combines extermination with expulsion of an identifiable ethnic group. Strongly associated with the war in the former Yugoslavia.

eugenics (ch 7): An early theory respecting genetic transmission of physical, social, intellectual, and moral qualities which sought to advantage “races” that it considered superior stock against those that it regarded as inferior.

evangelicalism (ch 7): In Christianity, a belief that salvation is achieved through faith in Jesus; individualistic in that redemption occurs at a personal, not a social level; evangelical denominations are often associated with fundamentalism as well.

Executive (ch 1): Also called the Cabinet. The highest offices — either elected or appointed — in Canadian politics: before the 1840s, a mostly appointed Executive Council led by the Governor General; after 1867, an elected body comprised of members of the current House of Commons and supported by a majority of votes in the House of Commons.

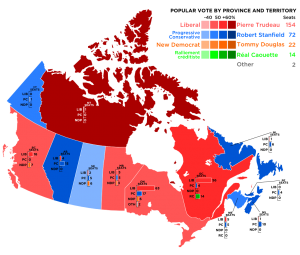

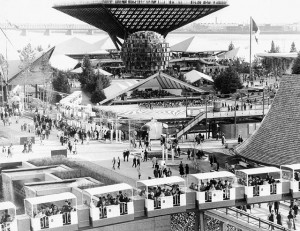

Expo ’67 (ch 9): A “World’s Fair” held in Montreal in 1967; part of the Centennial celebrations.

exurban (ch 5): Refers to residential lands that lay beyond the suburban fringe.

Fabian (ch 7): A belief that reforms to capitalism can produce a social and economic order of fairness for working people; sometimes called “gradualism.”

failed state (ch 12): A country that has no national administration; usually associated with civil wars.

Family Compact (ch 3): The elite network in pre-Confederation Canada that dominated colonial politics; in Quebec (aka: Canada East, Lower Canada) it was referred to as the Chateau Clique.

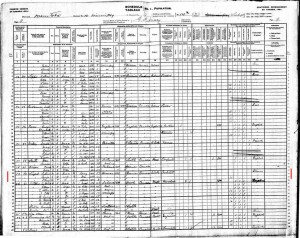

family reconstitution (ch 1): In demographic studies, the consolidation of population information from censuses, church records, and civic documents to enable a complete history of a family, street, or community in terms of births, marriages, deaths, divorces, movement, and other demographic behaviours.

fan identification and representation (ch 10): In the context of, principally, professional sports, the phenomenon of fan allegiance to a team or player; manifest in the wearing of sports merchandise or loyalty to a team or club, and consciously encouraged by local media.

Father of Confederation (ch 1): Term used to describe anyone involved in the Charlottetown or Quebec Conferences leading to Confederation; sometimes extended to the first premiers of the new Dominion as well; term sometimes used to describe Newfoundland Premier Joey Smallwood from 1949.

federation (ch 1): An assemblage of states or provinces with roughly comparable rights in which all the constituent parts relinquish some of their authority to a separate, central government.

Fédération National Saint-Jean-Baptiste (FNSB) (ch 3): Founded in 1907, francophone Catholic women activists who also saw themselves as maternal feminists.

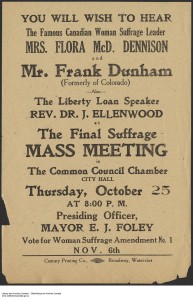

female suffrage (ch 3): One of the central issues of the first wave feminists, involving a protracted campaign with feminist activists laying claim to full political citizenship.

feminism (ch 3): An ideological position that advances the ideal of equality of women and men.

Fenian (ch 1): Irish-Americans, bound together as an anti-British army; mounted and/or threatened invasions of British North America in the 1860s and ’70s.

fertility transition (ch 7): Demographic trend in which populations move from a level of high fertility to a much lower level; associated with urbanization and modernization.

fifth column (ch 9): A population within a community that supports the efforts of an external force to topple that community or nation; examples include Cold War fears of Canadian communists who were loyal to Moscow rather than Ottawa.

first wave (ch 3): More fully: first wave feminists. Advocates for women’s rights in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; also sometimes called “maternal feminists.”

First Quebec Conference (ch 6): Held in August 1943; a top-secret high level meeting between leaders and representatives of the Canadian, British, and American governments. Canada’s actual involvement did not extend far beyond hosting the event.

Flag Debate (ch 9): Arising out of PM Lester Pearson’s decision to replace the Red Ensign in the early 1960s.

flapper (ch 6): Term used to describe fashionable young women in the interwar years; associated with hedonism, social rebellion, and style.

first-past-the-post (ch 7): Electoral system in which the candidate receiving the greatest number (though not necessarily a majority) of ballots wins; considered problematic by some when a party wins a majority of seats while winning much less than a majority of votes.

forward linkages (ch 8): Other industries are developed or expanded to help to link a product or staple export from the suppliers to the customers, as part of the distribution chain, for example, transportation, grain elevators, and port facilities.

fossil fuels (ch 3): Includes coal, oil, natural gas, and petroleum; any fuel based on the compression of carbon matter over geological time.

founder population (ch 1): A population deriving from a small initial influx of immigrants.

founding nations (ch 5): In Canada, typically refers to French and British Canadians.

Fourth World (ch 11): A category of mostly small and colonized indigenous populations around the globe; juxtaposed with First (northwestern European and North American), Second (Soviet bloc of developed nations), and Third (developing) Worlds; formalized with the establishment of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples led by George Manuel in the mid-1970s.

free labour (ch 3): Workers who are not tied to a feudal relationship, slavery, or indentured servitude and are able to move from one employer (or location) to another based on the size of pay and the character of the work.

free love (ch 9): Sexual relations outside of the institution of marriage; critical of the idea of marital monogamy.

free speech (ch 9): A movement that begins in earnest in the early 20th century, calling for the elimination of laws barring public discussion of any number of topics; some subjects regarded as seditious — including calls for violent overthrow of the regime — have been subject to intermittent bans.

Free Trade Agreement (FTA) (ch 8): Between Canada and the United States; signed in 1988, brought into effect in 1989; the FTA created a single market for most goods and services.

fruit machine (ch 12): A device intended to measure levels of arousal in a test subject; applied by Canadian security services in their efforts to identify sexual “deviants” and homosexuals.

Fulton-Favreau Formula (ch 9): A formula for amending the British North America Act (1867) developed in the 1960s; rejected by Quebec in 1965; provided the framework for subsequent discussions in 1982.

fundamentalists (ch 10): Any conservative theological movement that regards holy scripture as literal truth.

Galicia (ch 5): Term formerly used to describe an area of what is now part of Ukraine and Poland, which produced many immigrants to Western Canada. Also the name of a part of Spain, which did not.

garden city (ch 8): A movement among city planners beginning in the late 19th century imposed order on new communities, including extensive greenspace and boulevards. A garden city is simultaneously modernist and antimodernist.

general strike (ch 3): A labour stoppage involving most or all unions or workplaces. General strikes have been held that call on all workers in a particular city or a particular sector or across an entire country.

generation gap (ch 7): Notable differences in values, tastes, interests, and practices between individuals and whole cohorts from different generations. In the 1960s, used extensively to describe the conflict in values between people born before WWII and the baby boom generation.

Geneva Convention (ch 9): 1864, 1906, 1929, 1949; a succession of international agreements on the treatment of prisoners of war (POWs) and civilians.

genocide (ch 7): The premeditated extermination of an identifiable group of humans, often defined by race or ethnicity. See also cultural genocide.

Gentlemen’s Agreement (ch 5): 1908; also known as the Lemieux-Hayashi Agreement; the Japanese government agreed to restrict the number of people leaving Japan for Canada. A loophole allowing wives to join their husbands led to significant use of the “picture bride” system thereafter.

germ theory (ch 7): The identification of microorganisms as the cause of some illnesses, particularly infectious diseases.

ghost towns (ch 3): Abandoned communities; associated principally with resource extraction — often mining — towns that have a very short lifespan and which close up once the resource is removed or the market disappears.

Ginger Group (ch 7): An alliance of progressive MPs in Ottawa that led to the founding of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF).

gold standard (ch 8): In monetary policy, the linking of a nation’s currency to the value of gold, which is also called the gold exchange standard. Canada (and Britain) abandoned the gold standard at the start of the First World War, resumed using the system in 1926, and then left it permanently in 1929.

Gouzenko Affair (ch 9): Post-WWII espionage case involving a clerk at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa who disclosed the existence of a spy ring in Canada.

Governor-General (ch 6): The Crown’s representative in Canada; appointed by the King or Queen.

gradualism (ch 3), gradualist (ch 7): The idea that great change can occur incrementally, in slow, small, and subtle steps, rather than by large uprisings or revolutions. Among left-wing activists, a belief that reforms to capitalism can produce a social and economic order of fairness for working people; sometimes called “Fabianism;” derided by revolutionaries as delusional. In the context of Quebec’s independence movements the equivalent term is étapisme. See also reformist and impossibilist.

Grand Noirceur (ch 9): In Quebec, the period from 1944 to 1959 in which policies were introduced under the Union Nationale government of Maurice Duplessis.

graving dock (ch 2): Also called a dry dock; repair facility for shipping.

Great Coalition (ch 1): In 1864, an alliance between the Bleu-Conservatives and the Clear Grits in the Province of Canada. The Great Coalition launched a renewed effort to revise the Canadian constitution, a campaign that culminated in Confederation.

Greenpeace (ch 7): An environmental movement founded in Vancouver in the early 1970s as part of an international anti-nuclear arms movement; became more directly associated with environmental issues like sealing and whaling.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (ch 8): The value of all goods produced in a country during a specified period of time.

Group of Seven (ch 10): A group of artists (also known as the Algonquin Group) who emphasized landscape painting as the key to expressing Canadianness.

Harbour Grace Affray (ch 2): 1883 Newfoundland dispute in which Orange Lodge Protestants and Catholic neighbours came to blows; led to five deaths and a dozen casualties.

have-not (provinces) (ch 8): As opposed to “have” provinces, the prosperity of “have-not” provinces is below the average for the country as a whole; equalization payments were designed to address these inconsistencies.

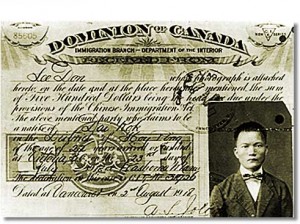

Head Tax (ch 5): A fee levied by the British Columbian and then the federal government on Chinese immigrants, beginning in 1885 and continuing to 1923.

Hegemony (ch 10): The dominance of a set of ideas or a particular group or social class.

high culture (high style) (ch 10): Also called high style; refers to cultural activities associated with elites; largely consistent across continents; spatially large with little differentiation (in contrast with vernacular styles which are spatially narrow and come in many forms); examples include classical music, liturgies, opera, many visual arts, theatre.

high modernism, high modernity (ch 10): A phase of modernism beginning in the interwar era and accelerating during WWII; characterized by a deepened confidence in science and engineering. See also big science.

hippies (ch 9): A youth movement originating in the 1960s that was anti-war (specifically, opposed to the war in Vietnam), critical of social conventions, and associated with experimentation with psychedelic drugs.

History Wars (ch 12): Conflict between generations of historians that spiked in the 1990s; pitted national/nationalist historians against historians of society and culture.

hobo jungles (ch 8): Homeless men’s camps, usually in marginal spaces in cities and towns, proliferated during the 1930s Depression.

homestead (prologue): A grant of free land of typically 160 acres available to males over 21 years of age, with the obligation that they “improve” no less than 40 acres and build a permanent dwelling on the land within three years; made available under the Dominion Lands Act of 1872; modelled on similar legislation in the United States.

homestead rights (ch 3): The Dominion Lands Act protected women’s interest in homesteads by forbidding the sale of the homestead by a husband without the wife’s written consent.

Home Children (ch 5): Over 100,000 children who were exported from Britain to Canada between 1869 and the late 1930s. Organized by charitable church organizations to alleviate overcrowding and to provide improved and more healthy alternatives. Stories of abuse abound, although many of the children who were distributed to farms across Canada did enjoy improved circumstances.

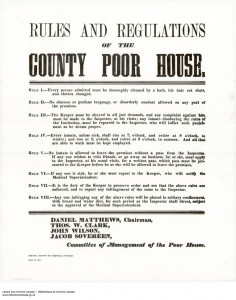

House of Industry (ch 3): A facility typically funded out of philanthropic/charitable donations that provides housing and food for impoverished citizens with the expectation that they will do work in return. In the 19th century, associated with workhouses for the poor.

household wage (ch 3): A way of measuring income that extends beyond the breadwinner model and incorporates incomes earned by every member of the household/family.

housewives (sing. housewife) (ch 9): A married woman whose principle (unpaid) occupation is the maintaining of her household, including preparing food, cleaning clothes, providing pre-school education, and cleaning house.

human rights (ch 5): Any right thought to belong to every person. Enshrined in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1947.

Hutterites (ch 5): Along with the Mennonites and Amish, the Hutterites are an Anabaptist sectarian group; emigrated from Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century, where they faced oppression for their pacifist beliefs and the practice of adult baptism; many arrived in Canada after attempts to settle in the United States. A communal farming community that resists modernization.

Hyde Park Agreement, Hyde Park Declaration (1941) (ch 6): A wartime pact between Canada and the United States; allowed Canadian-made goods manufactured for export to Britain to be covered under the Britain-USA Lend-Lease Agreement.

identity politics (ch 12): An orientation in politics that begins with a sense of oppression or loss among a constituency (an identity) and moves toward an agenda of initiatives that will address those inequities; distinct from ideological politics, which begin from a position of principles and ongoing goals that are society-wide.

Idle No More (ch 11): A peaceful protest and awareness-raising movement launched in 2012 by a group of Aboriginal and allies; catalyzed by Federal Government legislation that threatened Treaty rights.

illegitimate (ch 9): In legal and demographic terms, a child born to unmarried parents (or “out of wedlock”).

impossibilists (ch 7): Among left-wing activists, a belief that it is impossible to reform capitalism and that it must be overthrown rather than overhauled. See also gradualist and reformist.

Indian Agent (ch 2): An agent of the federal government’s Department of Indian Affairs (or, later, DIAND) with responsibility for managing and/or supervising one or more Aboriginal communities.

industrial relations (ch 3): The diplomatic business of negotiating contracts and conditions between employers and employees; typically between employers and labour organizations (unions).

information age (ch 8): A view of the post-industrial economy in which digitized information is the basis of a new economic order.

Institut Canadien (ch 10): Established in 1844 under the leadership of young francophone liberal professionals (physicians, lawyers, notaries, teachers) who sought to enrich and secularize Canadien life; provided the intellectual firepower of les Rouges.

intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) (ch 9): Cold War-era surface-to-air missiles with no less than a 5,000 km range; typically nuclear-tipped.

internationalist (ch 7): In the history of organized labour, the belief that workers of all countries had more in common than they did with co-nationals who belong to other social classes. Views nationalist movements as antithetical to the interests of working people.

International Olympic Committee (IOC) (ch 10): Established 1894; responsible for the organization and operation of the Olympic Games (both winter and summer versions).

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (ch 8): Created at Bretton Woods in 1944 to work with the World Bank to reinvigorate post-war economies by achieving currency stability, stimulating international trade, and rescuing national economies in distress.

interwar (ch 6): The period between 1918 and 1939.

Iron Curtain (ch 9): A term coined by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to refer to portions of Eastern Europe that the Soviet Union had incorporated into its sphere of influence and that no longer were free to manage their own affairs.

isolationism (ch 6): The policy of isolating one’s nation-state from international turmoil and alliances.

Jewish holocaust (ch 5): The campaign launched in the 1930s and early 1940s by the German National Socialist government aimed at the eradication of the Jewish population in Europe. Estimates of the number killed run to 6 million or more.

Jim Crow Laws (ch 5): In the United States, post-Civil War racial segregation laws that discriminated against African-Americans; most formal elements dissolved in the 1950s and ’60s in the Civil Rights Movement; was one cause of African-Americans emigrating to Canada in the Laurier and Borden eras.

jingoism (ch 6): Term coined in the 1870s; denotes patriotism applied in an aggressive foreign policy. Canada’s involvement in the Second Boer War contained elements of jingoism.

Juno (ch 6): The invasion of France in 1944 – code-named Operation Overlord – targeted a series of beaches, each of which was assigned its own operational name associated with alphabet call-letters. The American forces struck at Utah and Omaha; the British attacked Sword and Gold; the Canadian assault came at Juno. Originally the British and Canadian beaches were named for fish (i.e.: Swordfish, Goldfish) and Juno was called Jellyfish, but British Prime Minister Winston Churchill objected to the idea that soldiers were bound to die on a beach code-named “Jelly” and insisted on the change to “Juno.”

Kanakans (ch 2): Hawaiians or Pacific Island workers; this term may have been used disparagingly or in a derogatory fashion, however, the word means “human being” in the Hawaiian language.

Keynesian economic principles (ch 8): Named for the British economist, John Maynard Keynes, it broke with orthodox thinking by advocating government spending during downturns so as to stimulate the economy; these principles also encouraged aggressive taxation during times of prosperity to offset recovery-era spending. Resisted and rejected by orthodox economic thinkers and conservatives who deplore the idea of a large, bureaucratic, and interventionist state.

King-Byng Affair (ch 6): Also known as the King-Byng Thing, a constitutional crisis arising from Mackenzie King’s test of Governor-General Byng’s authority to call an election when requested by a Prime Minister.

Klondike (ch 9): The locus of the 1890s gold rush in the Yukon Territory, along the Klondike River valley; used to describe the gold rush as a whole.

Knights of Labor (ch 3): Fully, the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor. Established in the United States in 1869-70; expanded into Canada in the next decade; organized workers regardless of race (apart from Asians), sex, or skill levels. Competition with the new craft unions resulted in the Knights’ expulsion from the Trades and Labour Congress in 1902, and its gradual disintegration thereafter.

knowledge economy (ch 8): In the late 20th century, the trade in intellectual property and educational property; the preeminence of technological and other kinds of knowledge and information as economic drivers.

Korean War (ch 9): A war that began in 1950 and ended inconclusively in Armistice in 1953; this was Canada’s first Cold War era military engagement, and it involved significant casualties.

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) (ch 6): An explicitly racist, anti-Catholic illegal organization with roots in the American South; established a presence and substantial following in Saskatchewan in the 1920s, where it played a role in the outcome of the 1929 provincial election. Largely dissipated thereafter, the Klan briefly reappeared in the 1970s in British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario.

Labour Party (ch 3): In Britain, the political face of the Trades Union Congress; established in 1906. While Labour Parties also appeared in Australia and New Zealand, one never fully materialized in Canada.

labourism (ch 3): Canadian Liberal-Labour (Lib-Lab) candidates promoted an agenda that consisted mostly of democratic reforms, the 8-hour work day, a minimum wage, and educational opportunities for all.

Laurier boom (ch 8): The period of economic and demographic growth that coincides with the coming to office of the Laurier Liberals in 1896; concludes in 1912-14.

League for Social Reconstruction (LSR) (ch 7): A socialist think-tank established by Frank Underhill and F.R. Scott in 1932.

League of Nations (ch 6): A post-Great War international assembly established in 1919, of which Canada was a founding member. Its principal objective was to create conditions of collective security through a mutual defence pact and the application of economic sanctions; failed largely because of the United States’ refusal to join and member states’ (including Canada’s) fear of being embroiled in conflicts (military or economic) abroad.

Left (ch 7): Coined during the French Revolution to describe opponents of the monarchy; since then, used to describe a spectrum of reform and radical positions and political organizations that includes some Liberals, the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, the New Democratic Party, the Socialist Party of Canada, and — at the far end of the Left — the Communist Party and, in some instances, anarchists. See also Right.

Legislative Assembly (ch 1): Until 1968 all Canadian provinces had a Legislative Assembly, either as their only house of elected representatives or as a lower house — in either instance equating to the federal and British House of Commons. In 1968 the Quebec Assembly was renamed the National Assembly of Quebec. Sitting members are described in most provinces as Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) and in Ontario as Members of the Provincial Parliament (MPPs). In Quebec they are Members of the National Assembly (MNAs).

Les Automatistes (ch 10): Surrealist painters and performers based in Montreal, 1942-48; overlapped with the Contemporary Art Society.

Lend-Lease Agreement (ch 6): Prior to declaring war against the Axis Powers in 1941, the United States agreed to support the Allied war effort by selling materiel to Britain on a deferred-payment program. Canada was able to take advantage of this arrangement, which led to rapid industrial recovery and expansion. See also Hyde Park Declaration.

Liberal-Labour (also Lib-Lab) (ch 3): Typically a pro-labour candidate, sometime running under a Labour or Independent Labour banner, who joined the Liberal caucus on being elected.

liberalism (prologue): A political philosophical position that, in the late 18th and 19th centuries, enjoyed widespread acceptance; prioritizes the rights of the individual (that is, the individual adult male), private property, equality (again, among adult — typically white — males), and the values of a democratic system.

Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion (ch 7): A 1,500-strong contingent of Canadian volunteers in the war against the Fascists in Spain during the Civil War, 1937-38; took their name from the two leaders of the Rebellions of 1837-38, Louis-Joseph Papineau and William Lyon Mackenzie (the grandfather of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King).

Maître chez nous (Masters of our own house) (ch 9): The slogan used by Jean Lesage’s Liberals in Quebec in 1960 election, ushering in the Quiet Revolution.

Manhattan Project (ch 6): 1942-46; a secretive and international Second World War research and development project conceived to develop the first atomic bomb. Canada contributed the uranium and, at what was still a prototype reactor on the Chalk River in Ontario, developed the processes for extracting weapons-grade plutonium.

manifest destiny (ch 1): American notion that it could control, and was destined to control, the whole of North America; literally, it was the will of God (destined) and it was apparent (manifest) in the incremental territorial expansions of the United States.

Manitoba schools question (ch 4): In 1890 the provincial government turned its back on commitments in the Manitoba Act (1870) to provide a dual — French and English — system of education, a move that was stimulated by declining French and Catholic populations. The Privy Council determined (twice) that the federal government had the power to reverse this decision. In opposition, Wilfrid Laurier blocked Ottawa’s attempt at disallowance; in government he negotiated a compromise with Manitoba.

Maritime Rights (ch 8): An interwar-era political common front in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia that argued for greater federal support for the regional economy.

Maritime Union (ch 1): A proposal to create one colony out of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island; the original impetus for the Charlottetown Conference; abandoned in favour of Confederation.

marketing boards (ch 9): An agricultural producers’ marketing tool; often established by the producers themselves or by government, which acts as a buyer of output and then a marketer. Constitutes a kind of monopoly in that producers cannot sell their goods through any other means. See also wheat pools.

Marshall Plan (ch 8): Also called the European Recovery Plan (ERP), an American program giving billions of dollars of aid to rebuild European economies after WWII, in part to restore markets but also to offset the appeal of Communism.

Marxist-Leninist (ch 7): Building on the scientific socialism of Karl Marx, which argued that socialist, worker-led governments would supersede bourgeois capitalism, the Leninist thread — arising in revolutionary and post-revolutionary Russia — introduced the idea of a vanguard of the proletariat, single-party rule, internationalism, and a state-run economy. In Canadian communism, one of several variants on Marxist doctrine.

Mason-Dixon Line (ch 1): Boundary between the American colonies, then states, of Maryland and Pennsylvania; also used to define the American South from the American North, and slave and non-slave states.

maternal feminism (ch 3): Also called first wave feminism; a movement to achieve greater civic rights for women; based its appeal on the biological differences between women and men, arguing that women have a natural nurturing instinct and ability which ought to be welcomed in a democratic system; women could apply the knowledge and attributes acquired from their universal role as mothers to address various inequities and social ills.

maternal feminists (ch 7): Adherents to the ideals of maternal feminism.

mechanization (ch 3): The process of replacing manual labour with machinery; distinct from automation, which is a later phase in the deskilling process.

Medicine Line (ch 2): The 49th parallel north, so named by the First Nations of the Plains because it worked as an invisible barrier to stop attacks northward by United States soldiers.

mediums (ch 6): Individuals thought to possess the ability to act as a bridge between the living and the dead; they were the “media” through which messages could be transmitted; part of an early 20th century trend toward spiritualism that was fed, in part, by the enormous mortality of WWI.

Meech Lake Accord (ch 9): 1987; an agreement reached between all the provincial premiers and the Prime Minister that provided for a constitutional amending formula, a distinct society clause for Quebec, senate and Supreme Court reforms, and a devolution of some immigration issues to the provincial level. Despite a promising start, the Accord failed to achieve final approval.

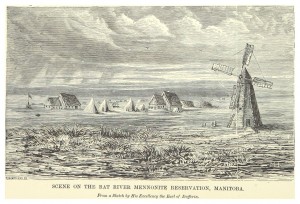

Mennonites (ch 5): Along with the Hutterites and Amish, the Mennonites are an Anabaptist sectarian group; emigrated from Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century, where they faced oppression for their pacifist beliefs and the practice of adult baptism; settled in communities in Ontario, in Manitoba and across the Prairies, and in parts of British Columbia. A communal farming community that has resisted modernization, though with less intensity than the Hutterites.

mercantilism (ch 8): The system of economic relations established between European empires and their colonies; emphasis is on the use of merchants in the home country to establish production in the colony of largely unprocessed goods that would be shipped to the home ports; leaves colonies economically dependent and underdeveloped.

Metro (ch 9): The federated Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto.

middle power (ch 9): The idea that Canada might occupy a position between “great power” states like Britain and the United States and, after the World War II, at a level between the superpowers (the US and the USSR), the second tier of military and economic powers (e.g.: Britain and France), and other nations; tied to Lester Pearson’s vision of peacekeeping and Canada as a referee or fair broker.

modernity (ch 3): Also modern and modernism; term given to a constellation of behaviours and beliefs associated with the industrial, urban era. It is associated with challenges to traditional values and ways of looking at the world, and is often used in connection with 20th century artworks, literature, and architecture.

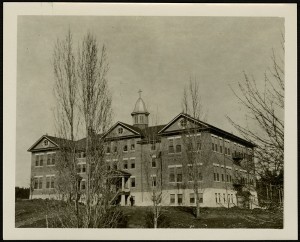

Mohawk Institute (ch 11): First industrial school for Aboriginal people, principally Mohawk; taught basic academic instruction and trades; based in Brantford, Ontario; opened in the 1830s under the auspices of New England Company.

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (1939) (ch 7): A mutual non-aggression treaty signed between Germany and the USSR; allowed Germany to move forward with its attacks on France and the Low Countries while the Soviet Union annexed territories in the Baltic region.

monetarism (ch 8): In macroeconomics, the theory that the money supply and central bank policies are key to understanding inflation and fluctuations in GDP. By controlling the money supply, monetarists argue, one can contain inflation. One instrument for achieving these goals is to raise interest rates — making money more expensive — and thereby reducing its velocity. Monetarist policies were introduced along with austerity measures in Britain under the Thatcher government from 1979. Similar efforts (without austerity) were attempted in the United States under Ronald Reagan. Both were influential on Canadian fiscal policy.

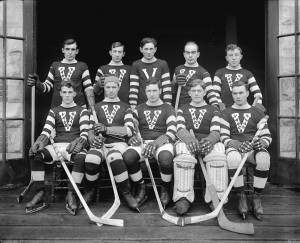

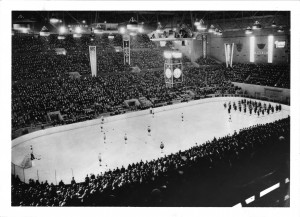

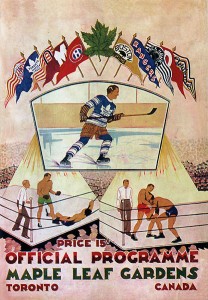

Montreal Amateur Athletic Association (MAAA) (ch 10): Created in 1881, a federation of non-professional sports organizations, including bicycling, lacrosse, and ice hockey clubs; argued for a gentlemanly view of athletics, one which built character and community; opposed to the professionalization of sports and games.

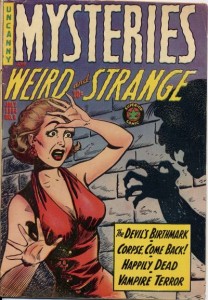

moral panics (ch 10): Public fears of declining values and worsening behaviours that could lead to social turmoil and/or crisis. Examples include temperance, anti-gambling crusades, the 1950s campaign against comic books, and several recurring moral panics regarding adolescents.

Moravian Brethren (ch 2): An early Protestant sect from central Europe; established missions in Labrador, with the first permanent site established at Nain in 1771.

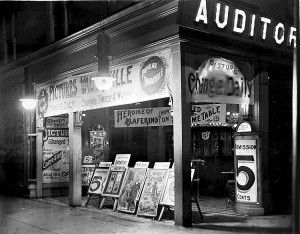

Motion Picture Production Code (1930) (ch 10): Also called the Hays Code, operated until 1968; established to address a public relations crisis in the film industry regarding risqué subject matter and scandals in Hollywood; prescribed anodyne subject matter and self-censorship by filmmakers as regards profanity, sex, nudity, and a long list of other perceived offences. It is worth noting that language, sexuality, and humour had a much wider berth in the first 30 years of the century.

muscular Christianity (ch 6): A late 19th century combination of Christian piety and athleticism, especially as regards masculinity.

mutually assured destruction (MAD) (ch 9): The Cold War belief that the sheer number of thermonuclear devices and delivery systems in the hands of the Soviet Union and the United States meant that neither side would survive an assault initiated by the other. By assuring their mutual destruction, they would be deterred from initiating a nuclear war.

nadir (ch 11): The opposite of zenith; it is the trough and in demographic terms it means the point at which a falling population bottomed out and from which it recovers. In the case of First Nations populations, they continued to fall until the 1920s at which point they began a steady recovery.

National Action Committee on the Status of Women (ch 7): Established in 1971 to agitate for implementation of the recommendations of the Bird Commission. See also Royal Commission on the Status of Women.

National Council of Women of Canada (NCWC) (ch 3): A feminist activist group formed in 1893; predominantly Anglo-Celtic Protestant women who mostly identified themselves as maternal feminists.

National Energy Program (NEP) (ch 8): Controversial legislation introduced under Pierre Trudeau’s administration in 1980-1985. The thrust of the policy was to secure Canadian oil for Canadian markets in eastern Canada (hitherto dependent on cheaper — but, in the context of the second OPEC shock, insecure — imported oil). Prices for Albertan oil in Quebec would be lower than in the United States (to which most of Canada’s oil was sent), which meant lower profits in the oil patch.

National Film Board (NFB) (ch 10): Established under the National Film Act, 1939 with a mandate to produce propaganda films during wartime. Subsequently a centre for creative excellence in documentary production.

National Hockey Association (NHA) (ch 10): One of several early 20th century professional hockey leagues and the direct precursor of the National Hockey League.

National Hockey League (NHL) (ch 10): Established in 1917 after a dispute among team owners in the National Hockey Association. It was, originally, an all-Canadian league but expanded in 1920 to Boston. Its higher salaries and American market led to the decline and disappearance of other professional leagues and the rise of an effective monopoly by the 1940s.

National Indian Brotherhood (NIB) (ch 11): Established in 1967-68 and propelled into action by the appearance of the White Paper (1969). See also the Assembly of First Nations.

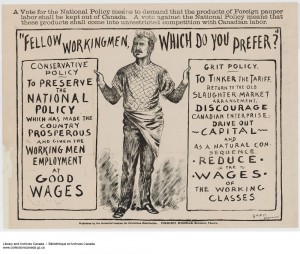

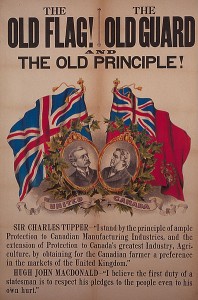

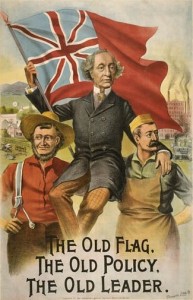

National Policy (ch 3): John A. Macdonald’s linkage of three policies into one: a tariff wall to exclude American manufactures; an transcontinental railway (the CPR) to link the Maritimes with British Columbia; and the settlement of the West. Although most of the components were in place by 1876, it was only touted as a single National Policy in 1879.

nationalist historians (ch 12): Or “national historians”; scholars who believe that the principal role of history is to analyze and explain the history of the nation state.

nationalization (ch 9): The imposition of state ownership over a corporation or sector; examples include the provincial nationalization of hydroelectricity providers (e.g.: Ontario Hydro, Hydro-Québec, and BC Hydro) and the water transport monopoly in British Columbia (BC Ferries).

nativist (ch 5): A movement or individual committed to preserving privileges to established members of a community over newcomers; often translates into anti-immigration attitudes; many nativists are themselves merely earlier immigrants; has nothing to do with Native peoples.

Nativist millenarians (ch 2): Movements among mostly Indigenous peoples under imperialism that attempt to throw off their occupiers and return to an idealized past way of living; sometimes imbued with a mystical element that could involve divine intervention.

natural increase (ch 1): The growth of population from more births than deaths; that is, not by immigration and not factoring in emigration.

neo-liberalism (ch 8): An ideological position that favours smaller government, deregulation, freer trade, and lower taxes; and is tied to monetarism.

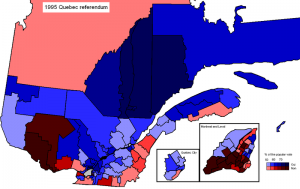

Neverendum (ch 9): The series of referendums dealing with Quebec separatism (or sovereignty-association) and proposed changes to the constitution, beginning in 1980.

New Canadians (ch 5): Term used since the late 1960s to describe recent immigrants, particularly those arriving from non-traditional sources like South Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

New Democratic Party (NDP) (ch 7): Successor to the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation; created out of the union of the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) and the CCF in 1961.

New Left (ch 9): Associated with campus radicalism in the 1960s and the writings of German philosopher Herbert Marcuse; less interested in the class struggle and labour power than with social justice.

New West (ch 8): Term used to describe the Prairie provinces following their move from a monocultural economy based almost entirely on grain production and export to an economy with diverse and more valuable bases.

New World Order (ch 12): In the context of the post-Cold War era, a United States-dominated international stage in which diminished expenditures on nuclear arsenals would be turned into resources to build up economies globally; in the context of wars in the Gulf and Middle East, an effort to impose the (Western) rule of law on recalcitrant states.

non-conformist churches (ch 7): A descriptive term attached to dissenting Protestant sects that broke with the Anglican Church as early as 1660; associated specifically with Methodism, Congregationalism, and the Baptist Church.

Nootka Sound (ch 5): On the west coast of Vancouver Island; traditional territory of the Nootka (Nuu-chah-nulth) First Nation; site of sustained contact between European, Mexican, and American traders and Aboriginal peoples, along with a significant population of imported Chinese labourers in the late 18th century.

North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) (ch 9): Arising from a pact signed with the United States in 1957; provides detection and defence against Soviet missile and other airborne attacks on North America.

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (ch 8): 1994; trade pact with the United States and Mexico. Expands on the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) signed in 1988.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (ch 8): Established by the North Atlantic Treaty of 1949 that brought together the Treaty of Brussels nations (Britain, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, and France), Canada, the United States, Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Italy, and Portugal as a mutual defense league — an attack on one would be an attack on all.

notwithstanding clause (ch 9): Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) allows any provincial, federal, or territorial government to override some select rights in the Charter for a fixed period of time.

nuclear family (prologue): Describes a household comprised of one or two adults and their children. Households that include adult siblings are called “consangineal” and those that include an older generation (that is, grandparents) is called “extended”.

numbered treaties (ch 11): Treaties struck between Canada and Aboriginal peoples from 1871 (Treaty 1) to 1921 (Treaty 11), covering a territory that stretches from Ontario’s eastern boundary in the North West to British Columbia, incorporating the whole of the Peace River Valley and the Mackenzie River drainage basin. Areas not covered by numbered treaties include southern Ontario (including the Rainy River area and Thunder Bay-Nippissing corridor, most of British Columbia, most of the Yukon and North West Territories, and all of Quebec, the Maritimes, and Newfoundland-Labrador.

Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (ch 9): 1993; set the stage for the Nunavut Act, 1999 that created the new territory of Nunavut; the first major land claims agreement negotiated by the federal government since Treaty 11 (1920 to 1921).

October Crisis (ch 9): This was a combination of events in October 1970 including the kidnapping of James Cross and Pierre Laporte, attempts to ransom the two men, the execution of Cross by his abductors, and the use of the War Measures Act for the first time in peacetime.

Official Opposition (ch 7): In parliamentary systems, the party with the second largest number of seats in the House of Commons. On occasion, the second largest caucus has refused the title of Official Opposition.

official party status (ch 7): The recognition of a political party’s representatives in an assembly as sufficient to merit certain parliamentary privileges, including the right to ask questions during question period. In Ottawa, the federal House of Commons requires that a party have no fewer than 12 MPs in order to qualify for official status.

off-shore production (ch 8): Manufacturing of goods or parts in another country.

Ogdensburg Agreement (ch 6): 1940, a wartime accord signed between United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King; produced the Permanent Joint Board of Defence.

oil patch (ch 8): Shorthand for Alberta’s oil industry, from mining and processing to sales and financing, from the field to the head offices in Calgary and Edmonton.

Oka Crisis (ch 11): In 1990 armed Mohawk band members from Kanesatake blockaded access to proposed construction site of a golf course in Oka; the arrival of Canadian Armed Forces troops was followed by disruptions of traffic through reserve lands to the south by the Mohawk band members from Kahnawake.