1

Textbook Cover

Student Success by Mary Shier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

© 2020 Mary Shier

The CC licence permits you to retain, reuse, copy, redistribute, and revise this book—in whole or in part—for free providing the author is attributed as follows:

If you redistribute all or part of this book, it is recommended the following statement be added to the copyright page so readers can access the original book at no cost:

Download for free from the B.C. Open Textbook Collection.

Sample APA-style citation:

This textbook can be referenced. In APA citation style, it would appear as follows:

Lead illustrator: Gordon Shier

Cover image attribution: “Lecture Hall” by Gordon Shier is used under a CC BY 4.0 Licence.

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-77420-079-7

Print ISBN: 978-1-77420-078-0

Visit BCcampus Open Education to learn about open education in British Columbia.

This book is dedicated to my students and educational advising clients from over the years.

My students constantly inspire and amaze me with their dedication and commitment to succeed, their perseverance in overcoming obstacles, and their abilities in juggling work, family, and life as they forge a path for their futures.

Those who came for educational advising asked many great questions, considered numerous options, and in many cases designed unconventional educational plans to suit their individual needs and goals.

It is through the experience of working with many of these students that I have formed a compilation of the factors influencing the many facets of student success.

This book offers study skills and practices for college and university students to help them make a positive transition to post-secondary education, learn how to be a successful student, and make the most of their learning experience.

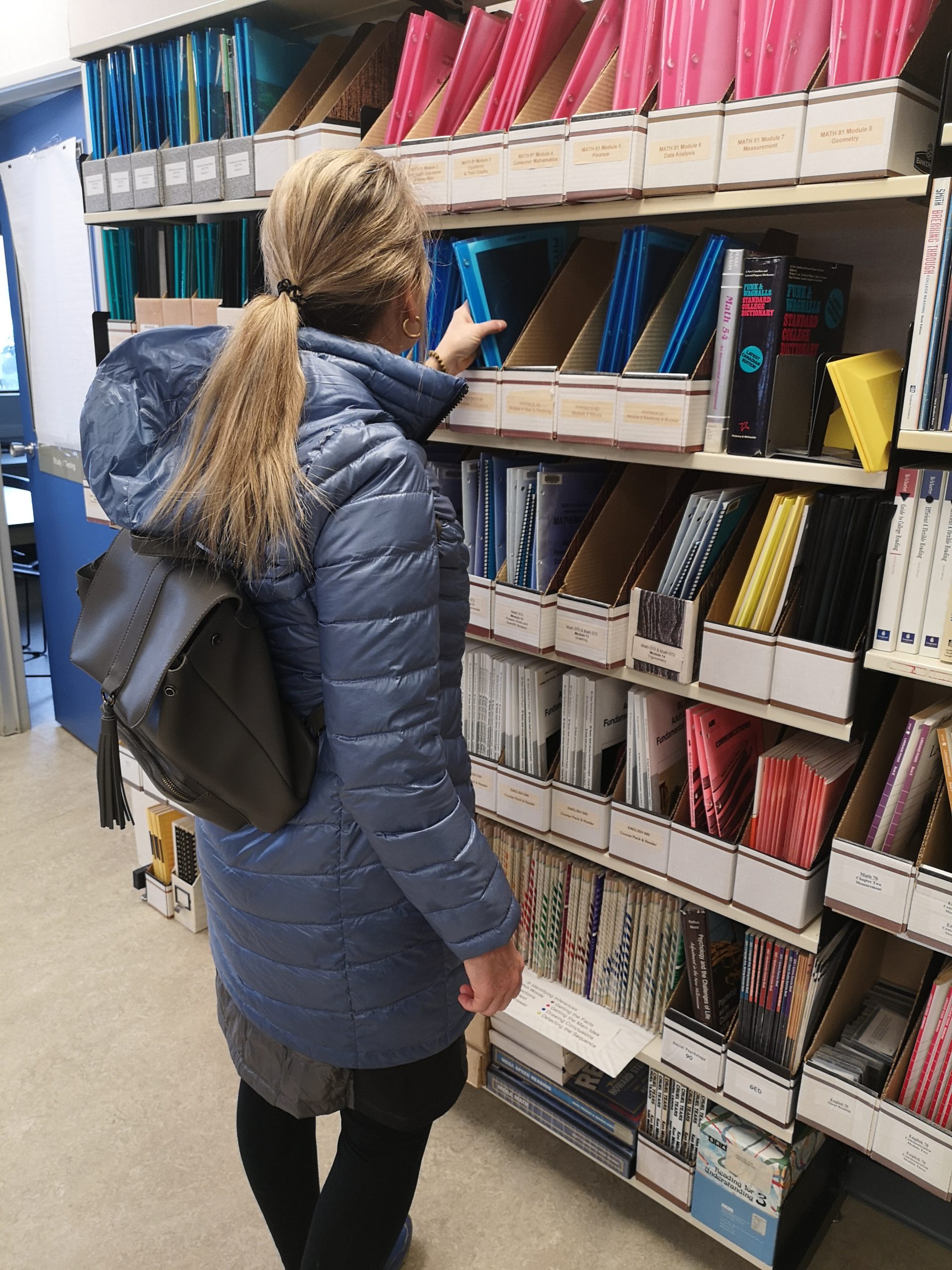

ABE. Although the book is useful for any post-secondary student, it was specifically created to provide a textbook for the British Columbia Adult Basic Education provincial level (ABE grade 12 equivalent level) course, Student Success for college upgrading students. Student Success is a course under the Education and Career Planning (EDCP) umbrella in the BC ABE Articulation Handbook, and this textbook includes content to cover all of the learning outcomes listed in the Handbook. The Student Success course can be used as one of the three electives required for the BC Adult Graduation Diploma. The first eight chapters cover the required learning outcomes and the remaining five chapters cover the optional learning outcomes. The optional topics are determined by the institutions offering the course and will vary between different institutions.

General Use. Students don’t need to be taking a Student Success course to benefit from this text. Post-secondary students can use this material to help them become better, more successful students. Faculty can use any parts of it to give to their students in any of their courses as applicable. Others can use applicable life skills chapters.

Open. The book can be used as a resource for students and faculty. Because it is an open educational resource (OER) with a Creative Commons licence, anyone can download the book and use all or part of it, modify and share it. People can access it for free online, download it as a PDF or eBook, or print it.

ZTC (formerly Z-Cred). Funding for the development of this book was provided by the Province of British Columbia Ministry of Advanced Education, Skills & Training through BCcampus Open Education. The funding was for an ABE Z-Cred initiative (zero cost credential), recently renamed Zero Textbook Cost (ZTC). The intent is to create pathways to graduation with zero cost. BC does not charge tuition for ABE courses—adults upgrading up to the grade 12 level. This initiative would provide pathways to adult graduation with free access to textbooks as well.

Independent modules. The chapters in this textbook are written as independent modules. They don’t build on each other, so students can complete any of the chapters without having completed prior chapters. Accordingly, instructors can use single chapters, or parts of chapters, and incorporate them into other curriculum.

Some of the chapters are useful even for those who are not post-secondary students, such as the chapters on time management, financial budgeting and planning, communication skills, personal wellness, technology skills, and presentation skills. Other chapters are very specific to student life, such as test-taking, study skills, memory skills, referencing sources, transfer credit between post-secondary institutions, online learning, student funding (student loans, bursaries, and scholarships), learning preferences and strengths, learning differences and challenges, and student support services.

Hopefully you will find numerous uses for the content of this book. This book includes a variety of techniques to help you cope with the demands of college and university. There are many useful life skills and student gems included.

Note. This text is a combination of original content and content “remixed” from parts of several open texts and adapted to meet the needs of the Student Success course. For more information, see the copyright statement.

For more information about open education in British Columbia, please visit the BCcampus Open Education website. If you are an instructor who is using this book for a course, please fill out our Adoption of an Open Textbook form.

In the beginning my motivation in compiling this resource was to create a textbook that matched the learning outcomes of the course that the EDCP articulation committee had recently created. In other words, I needed the textbook for my students and so did many other colleges in the province. Creating the textbook would provide a resource for a course that gave ABE students another course option for adult high school graduation – particularly important for students who aren’t math and science oriented. I loved the idea of creating an open text, as I support the concept of open educational resources (OER) to help keep costs down for students and to provide flexibility and ease for instructors who can reuse, adapt, and remix open materials to meet their needs. The timing was right and the funding was available.

What I started to realize as I became entrenched in the project was that I was putting to paper a compilation of the advice I give to students every day. As an ABE instructor and an education advisor, I see the pitfalls that overwhelm students on a regular basis. I see both the ways they set themselves up for failure and, conversely, the ways they adopt successful habits. I have worked in adult education for over thirty years, and – as I near the end of my career – in a way, writing this book was a cathartic exercise of compiling a tremendous amount of my experience and expertise.

My experience teaching and education advising has made me very aware of the struggles that many students go through. Being a good student does not necessarily come naturally; productive study habits are learned. Unfortunately, student retention rates and graduation rates are adversely affected because many students never learned what it takes to achieve success. Student Success can help develop strong study skills and inform students of campus services that can aid them along the way.

I believe in the value of education. I believe in life-long learning. I personally learned the hard way in my earlier years of education about the many bad habits that students form that only cause barriers to success. I experienced the difference in confidence and quality of learning when I implemented good, strong study habits when I embarked on graduate studies as a very mature (i.e. very old) student. Sharing some of this acquired wisdom regarding the habits that help students experience success just seems to make good sense.

One thing that I found really interesting in the process of writing the book was how many times I needed to take my own advice as I was writing it. It was almost eerie how many times it happened. For example, as I was writing the section on personal wellness, I was writing about the importance of keeping balance in one’s life, making sure to make time for physical exercise and fresh air. At the time of writing I had spent numerous very long days head down, writing content for the book. As I wrote, I realized my back and shoulders were aching, and I desperately needed physical exercise after so many countless hours at the computer. It was in the rereading of what I had written that it struck me how much I needed to heed my own counsel. Similar incidents happened in other chapters. Ultimately, this demonstrates that many of the skills require continual practice. Just when you think you have mastered something is when a new circumstance challenges you to practice the skill in a different way.

It is my hope that by using this text, students will develop skills that will set them up for a positive post-secondary experience that will reduce stress and frustration, and increase successful outcomes and graduation attainments.

A Note About Videos: There are videos throughout the text from external sources. For those reading the online copy, videos can be watched directly in the text. If you are reading a paper copy or a PDF, the text will provide direct URLs to where you can watch the video. You can also find those links in the back matter of the text named List of Links by Chapter.

Intended Audience: This book is useful for all college and university students, whether you are a young student barely out of high school, an older student making a career change, or a parent whose children have grown and gone and who is starting a new chapter of life. It is relevant whether you’ve never gone to college or whether this is your third time round. Regardless of your circumstances, you will likely want to make your educational experience worthwhile, learn the most you can, and do it in an efficient effective manner. My hope is that the concepts in this text will help you along the way.

All the best as you embark on your educational journey.

I would like to thank many people without whom I cannot imagine having been able to complete this project:

I met Mary Shier many years ago in Fernie, BC, where we both ended up seeking a life filled with outdoor adventure and teaching career opportunities. I had moved to Fernie to teach at East Kootenay Community College, now called College of the Rockies, and ended up spending 20 years teaching Adult Basic Education in the community. Part of my duties included being an Educational Advisor assessing adult students who wanted to improve their educational prospects but really didn’t know how to get there. It was an amazing 20 years of my life introducing the joys and frustrations of learning to students, and it gave me the skills and impetus to expand my career into leadership by becoming President of the Federation of Post-Secondary Educators of BC. I spent 16 years at FPSE, advocating for the educators in our system and our students as well. Good learning outcomes happen because all the pieces fit together, and when Mary asked me to write the foreword for her book, I didn’t hesitate.

I truly became a fan of Mary when she started teaching at College of the Rockies and we became colleagues. We were in crisis mode. A large resource industry in the local area had abruptly ceased operations and thousands of workers found themselves unemployed. Some ultimately went on to other jobs in the community, some moved out of the area for work, but many more needed to go “back to school.” The college was tasked with providing various educational opportunities to help the unemployed retrain and reskill.

As Educational Advisor, I conducted assessments on those who were now compelled to seek other work. It became apparent to me that a lot of remedial training was necessary; many did not have the literacy or numeracy skills to enter ABE. I particularly remember feeling rather despondent and wondering what we could do with them and how we could help them. That’s when Mary energetically said in no uncertain terms, “I’ll take them.” She meant it. She had a plan and she was going to help them succeed no matter what it took. She convinced us that her literacy program was the place for these students to learn the basics. She was right. Those students flourished under her tutelage and fairly quickly moved on to ABE. In the end, we experienced a zero attrition rate (previously unheard of) with the students going on to take further studies in everything from welding and small engine repair to X-ray technician and nursing. Mary was a huge part of those success stories.

Student Success is filled with Mary’s experience and knowledge over those 30-plus years. It is filled with practical advice for students who try to navigate all those wondrous moments that learning at the post-secondary level presents. From time management to financial planning to mental health and physical wellness, students and teachers will find advice and step-by-step strategies to smooth over the bumpy spots we all incur along the journey of our educational paths. She explains how to take good notes in class, how to be an active listener (including a check list!), how to mitigate test anxiety, how to follow a plan for success. The links to additional resources and research help to reinforce the strategies and provide students and educators alike with the ability to explore various topics in more depth if needed.

Mary wrote this book for a reason: she wanted to create a resource that would help students manage their own success, to give them agency over their future. In doing that, she also created a resource for educators, one that helps them recognize the value of taking time to truly engage with their students.

If you’re a student, read Student Success. If you’re an educator, read Student Success. I guarantee you will learn something.

Cindy Oliver BA(Hons), M.Ed

BCcampus Open Education believes that education must be available to everyone. This means supporting the creation of free, open, and accessible educational resources. We are actively committed to increasing the accessibility and usability of the textbooks we produce.

The web version of this resource has been designed to meet Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0, level AA. In addition, it follows all guidelines in Appendix A: Checklist for Accessibility of the Accessibility Toolkit – 2nd Edition.

This textbook is available in the following formats:

You can access the online webbook and download any of the formats for free here: Student Success. To download the book in a different format, look for the “Download this book” drop-down menu and select the file type you want.

| Format | Internet required? | Device | Required apps | Features | Screen reader compatible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online webbook | Yes | Computer, tablet, phone | An internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, or Safari) | WCAG 2.0 AA compliant, option to enlarge text, and compatible with browser text-to-speech tools. | Yes |

| No | Computer, print copy | Adobe Reader | Ability to zoom in, highlight, and annotate the text. | Unsure | |

| EPUB and MOBI | No | Computer, tablet, phone | Kindle app (MOBI) or eReader app (EPUB) | Option to enlarge text, change font style, size, and colour. | Unsure |

| HTML | No | Computer, tablet, phone | An internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, or Safari) | WCAG 2.0 AA compliant and compatible with browser text-to-speech tools. | Yes |

The following videos only provide auto-generated captions that may contain errors:

We are always looking for ways to make our textbooks more accessible. If you have problems accessing this textbook, please contact us to let us know so we can fix the issue.

Please include the following information:

You can contact us one of the following ways:

This statement was last updated on September 11, 2020.

Congratulations on your decision to attend college or university! For the great majority of students, it really was your decision—not just an automatic thing to do. If you happen to be one of the few who just sort of ended up in college or university for want of anything better to do, the benefits will soon become obvious.

The reason for this book is that post-secondary education requires commitment and effort. Like everything else in life that leads to meaningful results, success is not automatic. But when you apply yourself to your studies using the skills you’ll learn in this book, you’ll find that you can succeed.

When asked, most students say they’re in school primarily for the job or career they expect to follow after they get their certificate, diploma, trade, or degree. And they are correct that education pays off enormously in terms of future earnings, job security and stability, and job satisfaction. Every statistic shows that people with a post-secondary education will make much more in their lifetime on average (much, much more than the cost of schooling itself) and be much happier with the work they do.

But job and career issues are only a part of the big picture. An education results in many other personal benefits, and these also should be part of your motivation for doing well and continuing with your educational plans. Here are a few additional, less tangible benefits of a college or university education:

A college or university education is correlated with greater success in all those areas, even though most students are usually more concerned with making it through the next class or test than the rest of their lives. But sometimes it helps to recall what a truly great step forward you are taking!

Sadly, however, it’s important to recognize that some students do not succeed, and drop out within the first year. Sometimes it’s due to an unsolvable financial problem or a personal or family crisis, but the most likely reasons that a student in Canada will drop out include an ineffective social network (not getting involved in extra-curricular and volunteering opportunities), a lack of academic abilities, and poor attitudes and habits towards post-secondary education.Ma, X. & Frempong, G. (2008). Reasons for Non-Completion of Postsecondary Education and Profile of Postsecondary Dropouts. Retrieved from: http://publications.gc.ca/collection_2008/hrsdc-rhdsc/HS28-143-2008E.pdf

A book like this one can help you stay motivated when things get tough, but it can’t necessarily give you motivation to start with. That’s part of what you yourself have to bring to your education. You can be assured that you can learn the skills for succeeding in school.

Special skills are needed because the skills required at college and university aren’t the same as those required in high school. To name a few, there are differences in the study skills needed, in personal skills related to being independent, in social skills for getting along with instructors and others on campus, in financial realities, in matters of personal health, and more.

Remember, you can learn whatever you need in order to succeed. That’s what this book is all about. You’ll learn how to get the most out of going to class. You’ll learn how to study in ways that use your time efficiently and help you pass tests. You’ll even learn how to remember what you read in your textbooks. You’ll learn how to manage your time more effectively than you might have in the past, so that studying is less of a burden and more of a simple routine. You’ll even learn how things like eating well and getting enough sleep and exercise make it easier to do well in your classes.

One warning: you might not at first see an immediate payoff for everything you read in this book. When it comes to certain things, such as tips for how to take good notes in class to help you study later on for a test, you will get specific, practical advice you can put to use immediately to get a better grade. But not everything is as obvious or immediately beneficial. Some of the things you’ll read about here involve ideas you’ll need to think about. Some things will help you get to know yourself better, and understand more clearly what you really want from your education and how to go about attaining it.

However, if you care enough to want to succeed in school, and read these chapters and try to use the information, suggestions, and tips presented here, you will succeed in your educational goals.

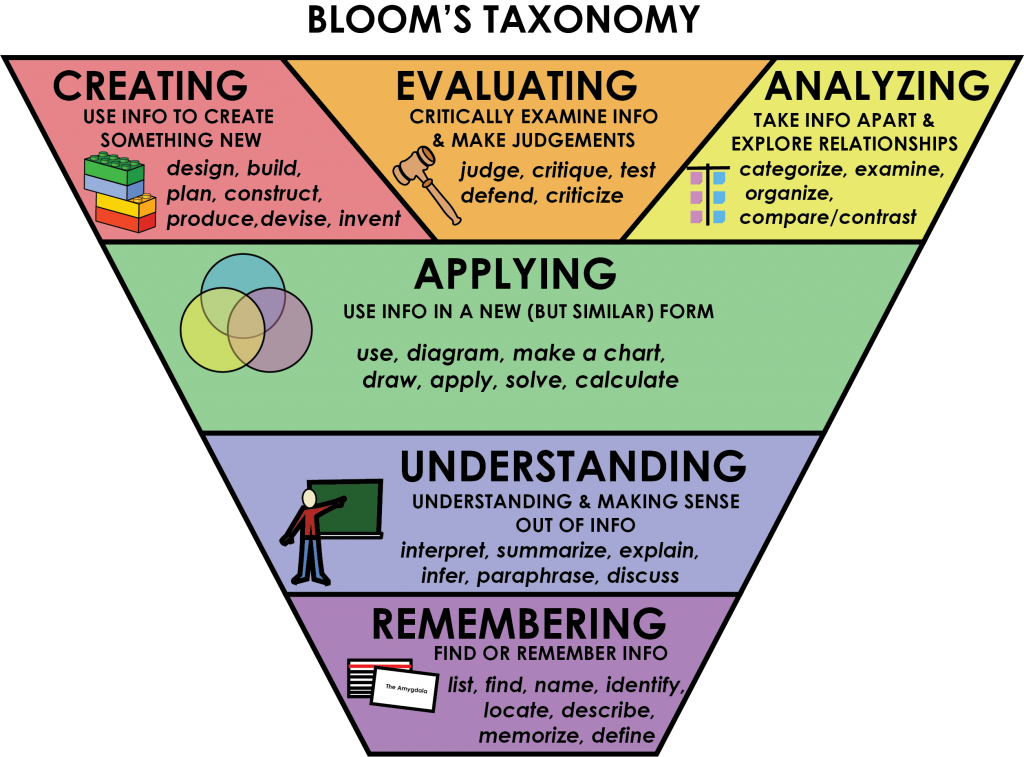

Being successful as a student doesn’t happen by accident. It takes strategy. Many people think students get the marks they get like a predestined event. But there are skills and methods to be successful which can be learned and practised. It all starts with taking stock of where you are now.

Exercise: Where Are You Now?

| Where are you now? | Yes | Unsure | No |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I understand all the benefits of a post-secondary education for my future life. | |||

| 2. I have clear-cut career interests and have already planned my college or university program to prepare me best for my future work. | |||

| 3. I am aware of how my previous educational background has prepared me for work in post-secondary. | |||

| 4. I have all the personal traits of a successful university or college student. | |||

| 5. I know how the learning process functions and make an effort to maximize my learning at each step in this process. | |||

| 6. I know my personal learning preference and use it to my advantage when learning new things. | |||

| 7. I know how to pay attention to gain the most from my classes. | |||

| 8. I am aware of my educational institution’s policies for academic honesty and behaviour on campus. | |||

| 9. I know where to find all the resources of my school that can help me succeed both academically and personally. | |||

| 10. I am confident I can earn the grades I need to achieve success in my courses. | |||

| 11. I know the first year of college will be the most difficult, but I am fully prepared and take responsibility for my own success. | |||

| 12. I am taking steps every day to ensure I am successful in every aspect of the school experience. |

Exercise: Where Do You Want to Go?

Think about how you answered the questions above. Be honest with yourself. On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate your present skills for succeeding in your program, with 1 being “not very strong” and 10 being “very strong”?

In the following list, select the three most important areas in which you think you can improve:

Are there other areas or skills that need more attention in order for you to succeed in school? Write down other things you feel you need to work on.

Learning Objectives: Here is Where We Will Go.

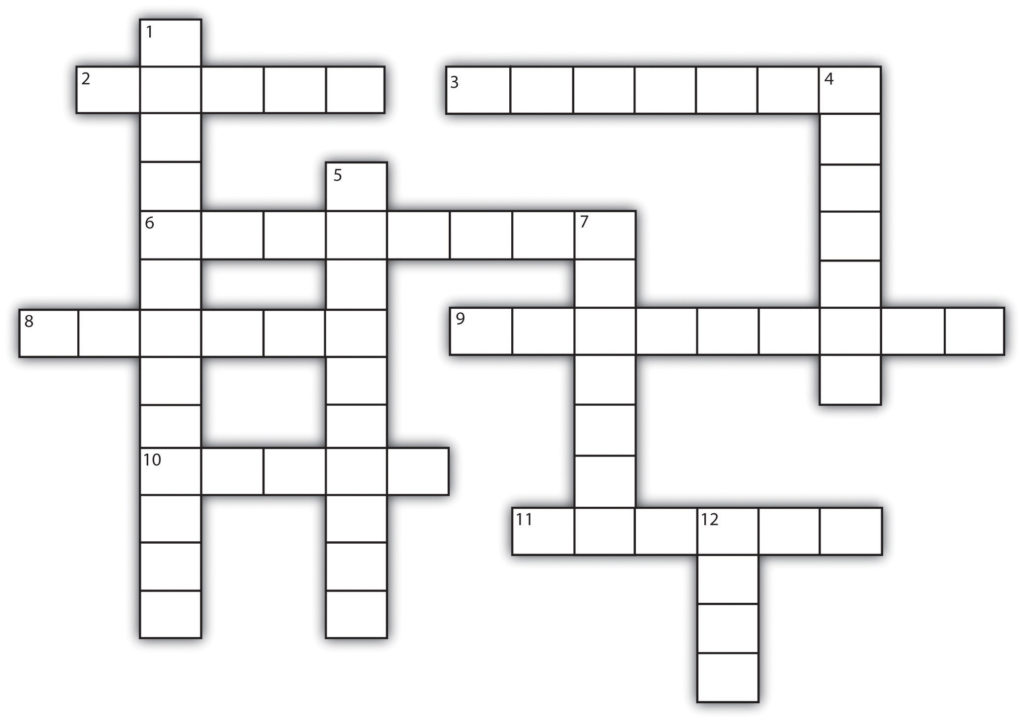

Here’s what we will work on in this book, Student Success. The following topics are covered by the thirteen modules of this text:

Detailed learning outcomes for each topic can be found in the introductions to each module.

Throughout this text you will have the opportunity to work on and develop skills in many of the areas you have identified above that will impact your student success. Some topics are specific to post-secondary while others will be useful in life in general, such as communication skills, financial planning, time management, and presentation skills. Hopefully this resource will give you many valuable skills going forward.

You may notice that there are references to hiking in the mountains throughout the text. That is because embarking on your educational path is much like starting a hike in the mountains. It is a bit daunting. It is natural to have doubts and fears about your ability to complete your goal. But it’s also exciting and thrilling. At many points along the way you’ll have surprising joys, unexpected challenges, and encouraging victories. Enjoy the journey!

This section was adapted from the following chapter:

So glad you’re here!

Congratulations! Whether you are starting a course on Student Success, or just reading a resource on Student Success, you have made an important decision in moving forward in reaching your goals. The goal of this text is to provide ideas, suggestions, and skills that will aid you in being a successful adult learner that will find your studies fruitful and rewarding.

If you’ve decided to move towards your goals through education, you will want to be successful in your studies. You will be investing a great deal of time and resources into your education, so it makes sense to get the most out of it. To be successful not only means achieving good grades, but it means learning useful concepts that will help you in your career and life. This book will help you to learn many things which can contribute to your student success. Take from it the things you feel will be most beneficial to you in your educational journey.

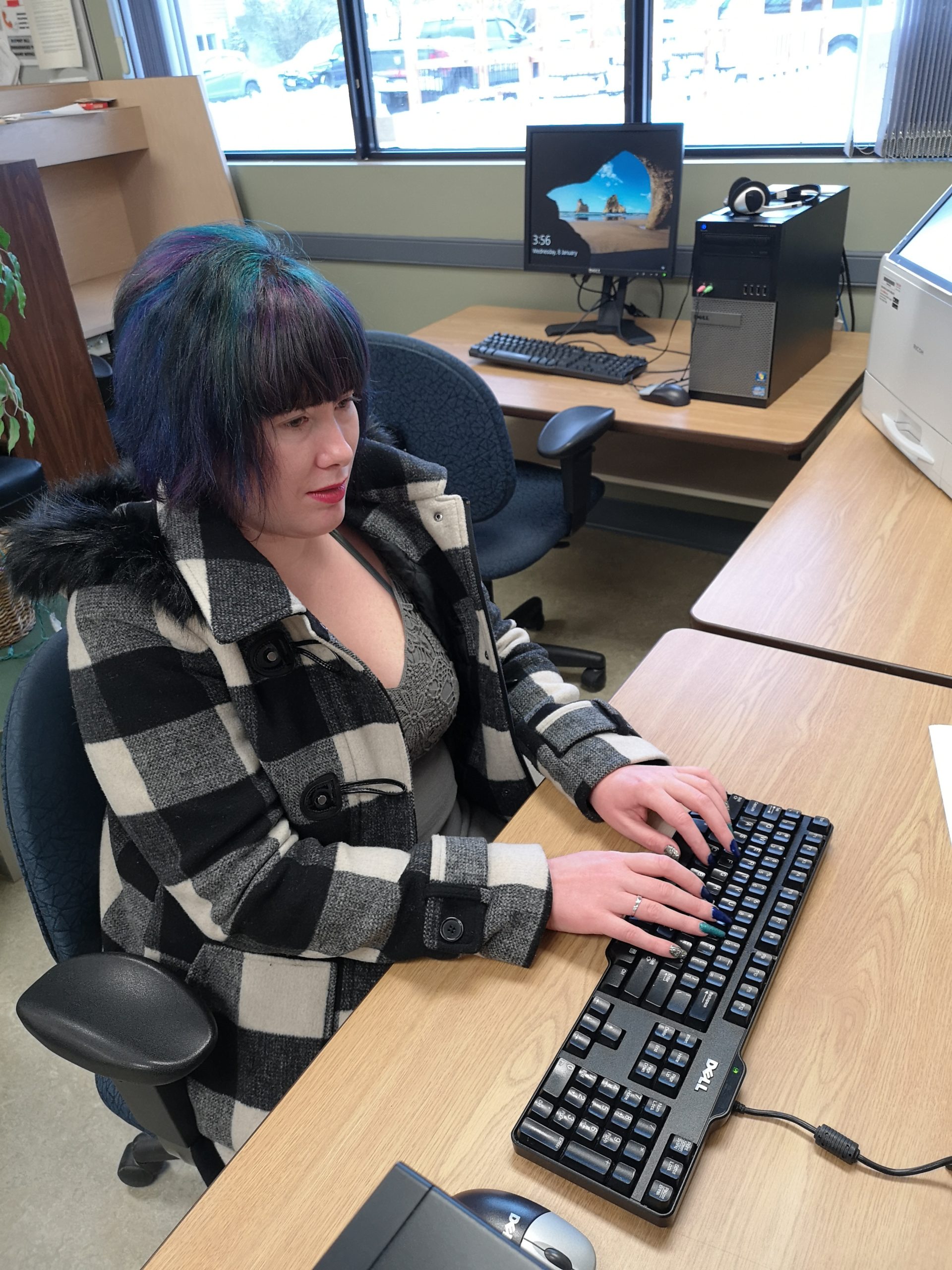

Depending on what kind of student you have been up to this point, achieving student success may mean you may have to do things differently than you have in the past. Some of you have very negative learning experiences which may cause concern over being a student again. Learning as an adult is often a very different experience and many students are surprised at how they can be successful now that they are adults and focused. Everyone has different strengths, different rates of learning, different learning disabilities and abilities, and each learner comes with different levels of education. All these things need to be taken into account to be successful. Learning as an adult is exciting. This module will focus on the many aspects of adult learning that will impact your success.

This module about adult learner awareness helps you identify the specific challenges you may face as an adult learner as well as recognize the advantages of your life experience to enrich your adult learning. It will help you realize the responsibilities of post-secondary education, many of which differ from those of high school. It will also help you evaluate different aspects of yourself in relation to returning to school as well as the impact of your returning to school on those around you that you care about. This module will also discuss many aspects of personal wellness which will help you to stay healthy and keep your life in balance as you do your studies. Finally, you will create a personal action plan to incorporate the many aspects of adult learning and to move forward in your educational goals.

Learning Objectives

In this chapter on “Adult Learner Awareness,” students will:

Learning as an adult is much different than learning as a youth in school. It has many challenges. Many of you will be taking courses at the same time as working, raising children, managing a household, or being involved in many community activities. Success in college will require balancing your obligations; time management will be crucial. It is important to be on top of your schedule and responsibilities and to ensure you are setting realistic goals for completion.

Many adults are very nervous when they first start in college. You may be asking yourself many questions. Will I be able to succeed? Will people think I’m stupid? I’ve been out of school so long- will I be able to learn and remember things? Don’t worry. You are not alone! Many students experience these feelings of anxiety and fear. You need to know that you are already a big step ahead of many people, because you have already made a commitment to move forward. It may have been nerve wracking to first inquire about getting started in post-secondary courses. For each one of you who has actually started taking steps (like reading this chapter), there are many more who have only thought about improving their education and haven’t made that first step and keep putting it off until another day. Congratulations! You are on your way.

It may help you to know that many students who have typically not done well academically in the past are pleasantly surprised at their ability to do well as an adult. This is due to many things. Often in elementary or high school, students have many issues which can prevent them from being successful. These include: undetected learning disabilities, health issues, personal issues, family crises, poor attendance, motivation issues, social pressures, bullying, abuse, dysfunctional families – the list goes on. These kinds of stresses can affect their grades negatively. And often students mistakenly begin to think that they are not capable. They can equate poor grades with being a poor student rather than making the connection that circumstances played a huge role in their ability to get good grades. It is very exciting to see students enjoy success when their circumstances have changed and they are motivated to succeed to reach their goals.

Of course, many adult students are also dealing with some very difficult personal circumstances of their own, and they are advised to access student support services and make an appointment with an education advisor to find out options for support.

You’ll be excited once you get started and realize how much you can enjoy learning.

As well as challenges of being an adult learner, there are also some salient advantages. Some of the most prevalent advantages to learning as an adult include:

It is important to understand how college and university is different from high school and how well your own past educational experiences have prepared you for what you will experience. This is another way in which entering post-secondary education “with your eyes wide open” will prove beneficial.

College is a unique experience for all students—whether you just graduated from high school or are returning to education after years of working or raising a family. You are transitioning from one form of education to another. Some students have difficulty because of the differences between college and high school.

Generally speaking, the university and college experience is usually different from high school in these ways:

What does all this add up to? For some students, the sudden independence and freedom can lead in negative directions: sleeping late, skipping classes, missing deadlines, failing to study adequately for tests, and so on. Other students who are highly motivated and work hard in their classes may also have difficulty transitioning to the higher academic standards of post-secondary. Suddenly, you’re responsible for everything. That can be thrilling but also a challenge to get used to. All the chapters in this book will help you make this transition successfully.

Exercise: Adult Learning

Think about your own educational experiences and answer the following questions.

Taking all of these things into account will help you embrace the idea of learning as an adult, and will help you let go of some of the old patterns and habits you had as a youth. Some people feel bad about going to school as an adult, thinking that it somehow represents failure to do it earlier. But in reality, those who intentionally keep on learning throughout their lives are the ones who continually upgrade their skills, learn new things, and are interesting people. Changing careers throughout life is a reality in this day and age. People go back to school to change careers at many ages. People go back to school to become more specialized at work, feed a new interest, or change their path. People engage in professional development throughout their careers to stay on top of technology, emerging trends, and current issues. People take workshops and go to conferences on issues they are interested and engaged in, just to stay on top of current teachings. People read books and have community groups to challenge each other and learn. Never be ashamed of learning! It keeps us young and informed.

The thing to remember is that life-long learning means that we constantly challenge ourselves, improve ourselves, and keep ourselves growing. Life-long learning is a great thing and continually contributes to our personal growth.

There are often specific classes available for seniors. Learning about computers for many seniors is exciting and challenging.

“Intellectual growth should commence at birth and cease only at death.”

— Albert Einstein.

Students have many responsibilities in a post-secondary environment. Many of them are responsibilities they didn’t need to worry about when they were in high school, or at least to a much lesser extent. When you start college or university, you are responsible for your own learning, and if you recently finished high school that means taking care of business you may never have considered before.

Author’s story

I remember a student who spent her entire student loan the week she received it. I’m sure she felt that she needed the things she bought, but she failed to follow a financial plan that would ensure success. Though she worked hard to get into her program, she “blew it.” Her financial struggles resulted in her failing out of the program in her first semester.

— Mary Shier, College of the Rockies

Exercise: Student Responsibilities

Of the student responsibilities listed above (or of other responsibilities you think of) name the top two you think will be most important for you to focus on to attain student success and state why.

Succeeding in college is rather like succeeding in life. It’s really much more about you than it is about school. So, the most important place to start is to consider why you’re here, what matters to you, and what you expect to get out of it. Even if you have already thought about these questions, it’s good to reaffirm your commitment to your plan as we begin to consider what’s really involved in being a student.

Take a few minutes and write down short answers to the questions below. Be honest with yourself, and write down what you really feel. You are not writing for an instructor here—so don’t answer what you think someone expects to hear—and you are not being graded on your answers! This is for you.

Exercise: Your Post-secondary Plan

Were you able to easily answer the questions? How confident do you feel about your plan?

These are important questions to think about for the simple reason that students who have a clear plan and who are prepared to overcome possible obstacles that may arise along the way are much more likely to succeed. In other words, just thinking in a positive way about your future can help that future come true!

The word values refers to “important and lasting beliefs or ideals shared by the members of a culture about what is good or bad and desirable or undesirable.”What are Values? (2016). Business Dictionary. Retrieved from: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/values.html What makes you feel good? What things would you be doing if you had all the time, money, and opportunities in the world? Questions like these help us define our own values.

Author’s story

I am very fortunate to live in the Rocky Mountains. It is absolutely gorgeous, and I never take it for granted: the stunning views, the fresh air, the smells of nature, the sounds of birds singing, the wildlife. I love that I can literally step outside my door and go for a beautiful walk in the woods. I can also go for a hike to a mountain peak with friends and be home for dinner. I value this time immensely, and it is an activity I wouldn’t willingly give up. It contributes to my physical, spiritual, and emotional dimensions of self and helps me be more effective in all areas. Taking time for hiking up mountains pays off enormously. What do you value that is non-negotiable?

— Mary Shier, College of the Rockies

Thinking about your own values can help you know what you want from life and from your education. Take a moment and consider the list of things in the following activity that are valued by some people. For each value, rate how important that thing is to you.

Exercise: Your values

Following is a list of things that different people say they value. For each item on this list, indicate how important it is to you by ranking it as very important (5), not important (0), or somewhere in between.

| Value | Ranking (From 0 to 5) |

|---|---|

| Making a good income | |

| Having good friends | |

| Learning new things about your interests | |

| Having a nice car | |

| Having intelligent conversations | |

| Staying current with the news | |

| Playing sports | |

| Hanging out with friends | |

| Playing computer or video games | |

| Cooking | |

| Online social networking | |

| Sleeping | |

| Reading a good book | |

| Travelling to new places | |

| Shopping | |

| Being liked by others | |

| Studying and reading textbooks | |

| Having nice clothing | |

| Watching television | |

| Enjoying time alone | |

| Getting out in nature | |

| Working your job | |

| Looking good, personal hygiene | |

| Meeting new people | |

| Going to movies or entertainments | |

| Eating nice meals out | |

| Exercising, being physically active | |

| Being your own boss | |

| Having a positive romantic relationship | |

| Engaging in your hobbies | |

| Setting your own schedule | |

| Volunteering your time for a good cause | |

| Cleaning house | |

| Attending classes | |

| Going to religious services | |

| Talking on the telephone, texting, email | |

| Going to parties | |

| Participating in clubs, organized activities | |

| Other: __________________________ | |

| Other: __________________________ |

Look back at the values and activities you rated highly (4 or 5), which probably gave a good indication of how you enjoy spending your time. But now look at these things you value in a different way. Think about how each relates to how you think you need to manage your time effectively while in school. Most students feel they don’t have enough time for everything they like to do. Do some of the activities you value most contribute to your college experience, or will they distract you from being a good student?

Students who enter college or university with their eyes open and who think about their own values and motivations will be more successful. If you have a good idea of what you want from life, the rest of it can be learned. In this book you’ll learn how to stay motivated, manage your time well, study well and many other things that will help lead you to success.

As you consider your values, it can be useful to think of them in terms of the dimensions of self: physical, spiritual, intellectual and emotional. Changes in your goals and routine will impact all these dimensions. Have you considered the impact returning to/continuing in school will have on the different dimensions of your self?

For example, the intellectual side of yourself will likely be stimulated and stretched. However, if you normally tend to spend a lot of time with friends but have to cut down on socializing time in order to implement good study skills, how will that impact your emotional self? Can you incorporate study groups into your study plan to help feed the emotional self’s need for interaction with people? If you need to stimulate the physical self through fitness, can you plan to review and listen to lectures while going for a run or bike ride? It may just take getting into the habit of downloading lectures onto your cell phone and taking them on the go. What are some ways to keep your spiritual self nourished through your demanding load at school?

Exercise: Dimensions of Self

Evaluate the spiritual, physical, intellectual, and emotional dimensions of self in relation to returning to school.

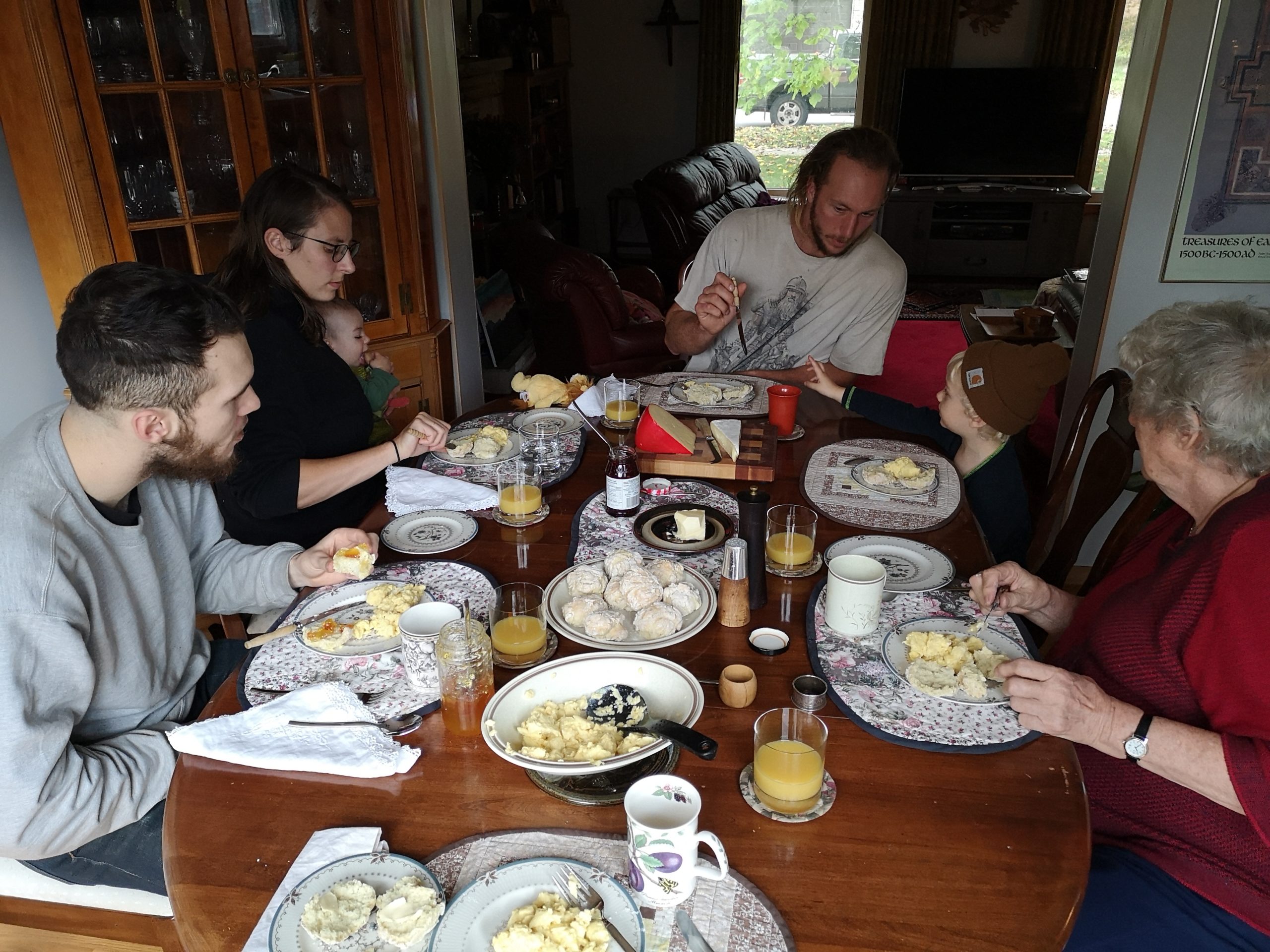

The decision to return to school doesn’t only impact you. It impacts family, friends, and co-workers. It often means that you are no longer as available to people as you normally are. This can impact others in numerous ways. Sometimes people are resentful because they feel they don’t have as much of you as they are accustomed to. Others are incredibly supportive and step up in ways that you never expected. One thing you can count on is that it will change things. You will need to keep the lines of communication open and not just pretend everything is as usual.

Families need to understand why your goals are important not just for you, but for the whole family. Have discussions not only about what you want to accomplish, but why. Identify the outcomes you see from doing this. That will help your loved ones get on board. Families need to discuss how the family will support you in your goals. Often that means a redistribution of chores and responsibilities. For example, teenagers can take responsibility for a regular meal night. It’s important to discuss things in advance so expectations are clear. Having a family that supports you in your goals can be a huge boost to your success.

Look for signs that your schooling is impacting those around you – either positively or negatively. Whether at home, at work, or in important relationships, you may need to reaffirm relationships so that others aren’t hurt by the fact that you have replaced time with them for time investing into your future. Reassure them that it is temporary. Paint a picture of how things will change once you’ve finished your schooling. Thank people for stepping up to the plate for you, whether it’s at work or at home, a little or a lot. Gratitude goes a long way.

Exercise: Impact on Others

Think about the people who are important to you that will be most impacted by you going to school.

Personal wellness means being physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually healthy. A healthy lifestyle helps balance all these aspects to achieve wellness. Your decisions and choices will impact both your short-term and long-term wellness. It is important to take into account your overall personal wellness in order to increase the potential for academic success in your educational program and get the greatest benefit out of it. In this section you will learn about some of the various aspects affecting your wellness, such as nutrition, fitness and lifestyle choices. You will assess your personal wellness and identify goals for improvement.

There are many lifestyle choices that we make that impact our personal wellness; negative choices can become vices and cause addictions that can impede wellness for a few hours or lifelong, as well as positive choices which can promote health and help form healthy habits. Some of the most rudimentary lifestyle choices are choosing to nurture and protect your body.

As well as looking after your physical health, it’s also important to look after your emotional health. Emotional health keeps your heart in check, and helps you to keep your emotions reasonable. Here are some ways to stay emotionally healthy.

Your mental health can be impacted by hormonal or chemical imbalances, circumstances, and lifestyle. This is a complicated issue, and in cases of serious depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues, it is important to get medical help through a doctor, counsellor, psychiatrist, or other health professional. But everyone, no matter what level of mental health, needs to keep stock of their mental health. Keeping in a state of wellness can be helped by using these strategies:

As well as looking after your physical, emotional, and mental health, you also need to look after your spiritual health. Your spirit is the deepest part of you – the part that makes you you. Spirituality is different for everyone. It is what provides you with meaning and purpose in your life. Your faith, values, beliefs, principles, and morals define your spirituality. For some, spirituality is nurtured through traditional religions, while for others it comes through relationships or being at peace with nature. Spiritual wellness brings inner peace, strength and hope. There are a number of ways to achieve spiritual wellness depending on your beliefs.

What are some other ways you develop your spiritual health?

Of course, in many of these aspects of personal wellness (physical, emotional, mental, spiritual) everyone will veer from good habits at least every now and then. But it’s good to keep them in check and be conscious of the impact of the lifestyle choices you are making. Too much of anything can become a destructive force in your life. Do you spend too much time on your cell phone, watching TV, on social media, on the internet, or playing video games? Is there something you do in your life that you know you should scale back on?

Reflections of a Former Student: Positive and Negative Influences

Peers

One of the most difficult things to come to terms with regarding your personal well-being is the people you spend time with. Many of us choose our friends based simply on who makes us feel the most comfortable, but being comfortable with a bad situation can be a negative thing in the long term. While close bonds with your friends are extremely important, it’s also vital to evaluate every once in a while: Do the people I spend time with uplift me? Do they reinforce habits, behaviours, and thought patterns that better my well-being, or are they holding me back? This isn’t as simple as spending time with only “positive” people with nice things to say to you. This is about finding people who are willing to challenge your weaknesses and push you to succeed on your own terms, while also being aware of your emotional needs. Finding this balance is incredibly difficult, and letting go of unhealthy relationships can be one of the hardest things we’ll ever have to do in life.

Media

Furthermore, in the modern world, this goes beyond just the people we give our time to, but also extends to our relationships with the various media we consume. Ask yourself, do you have a tendency to always engage with dark and violent movies, or depressing music? These things aren’t inherently bad to enjoy, and can be a healthy emotional outlet during the times when we deal with our own dark emotions, but media consumption can be thought of like a diet, and needs to be balanced as such. The emotional connection we get from media can become addictive, and if you find yourself always coming back to media that puts you in a depressed or angry state of mind, try integrating a little more variety into your media diet. By no means does this mean abandoning your personal taste for horror movies, for example, but once in a while try to throw on a good rom-com, and engage with it emotionally rather than judgmentally. Contrast the experiences you have with different media, and you will have a fuller experience with your engagement as a whole. It may even make you appreciate your old favourites in a whole new light!

— Gordon Shier, illustrator and animator

What you’re doing now in terms of personal health will have a significant influence on your academic performance. Setting healthy habits early on will improve both your academic performance and long-term health.

Considerable research has demonstrated that the basic elements of good health—nutrition, exercise, not abusing substances, stress reduction—are important for preventing cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancers, and chronic respiratory diseases, known to be the causes of nearly two thirds of deaths worldwide The National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648-6. The key risk factors for these non-communicable diseases are high blood pressure, smoking, high BMIs, low physical activity levels, alcohol consumption, and poor diet.

Wellness is more than just avoiding disease, however. Wellness involves feeling good in every respect – in mind and spirit as well as in body. Good health habits also offer the benefits of increased energy; better focus; less stress; more resilience; less lost time due to colds, flu, infections and other illnesses; more restful sleep; and improved mental health.

This video from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention introduces the positive benefits exercise has on health including disease prevention, longevity, weight control, and better sleep. It also explains aerobic activity and muscle strength training.

Video: “Physical Activity Guidelines” (length 4:42)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lEutFrar1dI

It’s also interesting to note how different dimensions of health affect each other. Physical health can impact emotional health and mental health.

Video: “Exercise and the Brain” (length 4:18)

This neuroscientist, Wendy Suzuki, explains the positive impact exercise has on memory, learning, mood and health. In fact, it highlights the brain-changing effects of exercise in this fascinating Ted Talk.

Video: “The Brain-changing Effects of Exercise | Wendy Suzuki” (length 13:03)

The next video talks about the effects exercise has on mental wellness for students.

Video: “Exercise and Mental Health” (length 3:35)

Exercise: Personal Wellness

Consider the various aspects of personal wellness and health (physical, emotional, mental, spiritual) listed in this unit and take an inventory of your own wellness. In what ways are you doing well? What ways could use improvement? Can you set some short and long term goals for your personal wellness?

Your report should be approximately one page.

One activity can contribute to many aspects of personal wellness. An outing such as hiking incorporates physical exercise, fresh air, social time with friends, and time of contemplation in nature.

To create an action plan, you will take all the information you have gathered in all of the activities in this module, and you’ll put it all together. At the end, you’ll have a realistic plan to help you realize your goal of returning to school. The action plan is the map to the next part of your journey.

What are the benefits of having an action plan?

Creating your action plan is a helpful step towards reaching your goals.

Exercise: Action Plan

When creating your Action Plan you may involve the help of others who may offer helpful suggestions.

Use your word processing program to answer the following three questions. Fill in as much information as you can. You won’t be able to complete the whole thing, but you will have enough information to finalize your plan to incorporate the concepts in this module. Review the exercises you have completed in each section of this module for ideas of things you need to include. Here are the categories to fill out:

Make sure your plan meets your needs. Finalize your plan and set out your next steps. Remember, you can always adjust your plan as needed. You may discover other things that need to be added or adjusted.

Your journey is not over — it has just begun!

In this chapter, you have investigated many aspects impacting adult learning. Keep these factors in mind throughout your education so that you remind yourself to keep things in check. Your action plan should be a summary of things you need to be doing to help you with student success. Add to it as you go through the course and discover other helpful practices. Hopefully this module has inspired you to embrace the idea of adult learning.

Exercise: Adult Learning

Key Takeaways

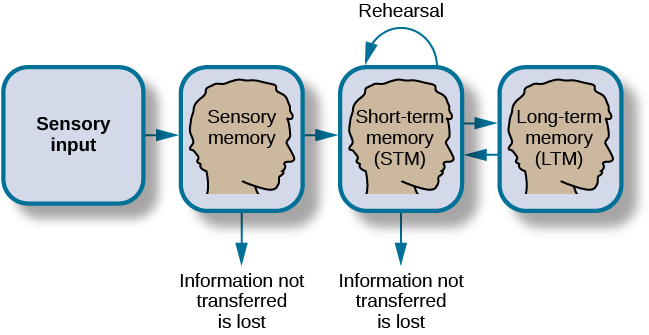

This module recognizes that all people learn differently. Learners have different learning preferences, strengths, and challenges, and they can utilize different strategies to make their learning most effective. Learning preferences include the mode or combination of modes that learners tend to prefer or respond well to, including aural, visual, verbal, and kinesthetic. Some people learn well by specifically including one or more of: reading, listening, speaking, watching, or practising. Memory is most enhanced when a combination of modes are used. Some types of learning work better with some modes. For example, when it comes to learning to ski, it is much more efficient to practice it than to read about it. Along with the type of learning and the preference of the learner, it is good to note that individual learners have different strengths and abilities. Utilizing these to the fullest makes for better learning.

Along with preferences and strengths, learners have different challenges. These can come in the form of learning challenges or challenging circumstances. Learning challenges can include learning disabilities of varying degrees, or if not diagnosed disabilities, learning struggles that have impeded ability to learn in the past. Challenging circumstances that affect learning can include temporary or long-term circumstances that impact ability to learn such as losing a loved one, medical conditions, or dysfunctional living conditions. These often have a negative impact on learners’ abilities to be successful at school.

Identifying and recognizing all these factors impacting learning will help you to examine different strategies and supports to help you to maximize your learning at post-secondary.

Learning Objectives

In this chapter on “Learning Preferences,” students will:

Different people have different learning preferences. There are many models which are used to describe these preferences. Learning styles is one that accounts for learner differences, which can be useful in understanding the different ways we learn. It can also be useful to know your strengths and use them to enhance learning.

Style refers to a student’s specific learning preferences and actions. One student may learn more effectively from listening to the instructor, while another prefers to take notes. Another learns more effectively from reading the textbook, while another student benefits most from charts, graphs, and images the instructor presents during a lecture. It’s important to note that people don’t necessarily have a single style. Students can use different styles in different situations, but they often tend toward specific preferences.

Learning style is important in college and university. Each different style, described later in more detail, has certain advantages and disadvantages compared with other styles. None is “right” or “wrong.” You can learn to use different styles more effectively.

Instructors also have different teaching styles, which may or may not match up well with your learning preference. Although you may personally prefer a certain style of teaching, you cannot expect that your instructors will use exactly the style that you prefer. Therefore it is important to know how to adapt to teaching styles.

It is important to note that there are many criticisms of the learning styles model. Some researchers purport that there is no evidence that identifying a learner’s learning style and then teaching to it accordingly results in increased student outcomes. Another criticism is that identifying one single learning style or method of learning and focusing on it alone can result in ignoring the other learning modalities, and this could ultimately hamper learning. It is much more useful to think of it like this: if you recognize a learning strength, then use that strength by adding more of it to your learning strategies. But don’t stop using the other modalities. For example, if you discover that listening is a strength for you, then it would be useful for you to add listening activities to your coursework, such as downloading lectures and re-listening to them while you are doing other activities (riding the bus, going for a run, or doing the dishes). But listening to lectures on your phone should not replace attending classes, practising concepts by doing homework questions, or working together in study groups – as these are all things that can enhance your learning as well.

Consider the following theories and see if any of the concepts resonate with you.

Often, we associate learning in university with strengths in reading and writing. Though it is true that reading and writing are important skills used in many courses, you can also apply other learning strengths to contribute to successful learning.

Different systems have been used to describe the different ways in which people learn. Some describe the differences between how extroverts (outgoing, gregarious, social people) and introverts (quiet, private, contemplative people) learn. Some divide people into “thinkers” and “feelers.”

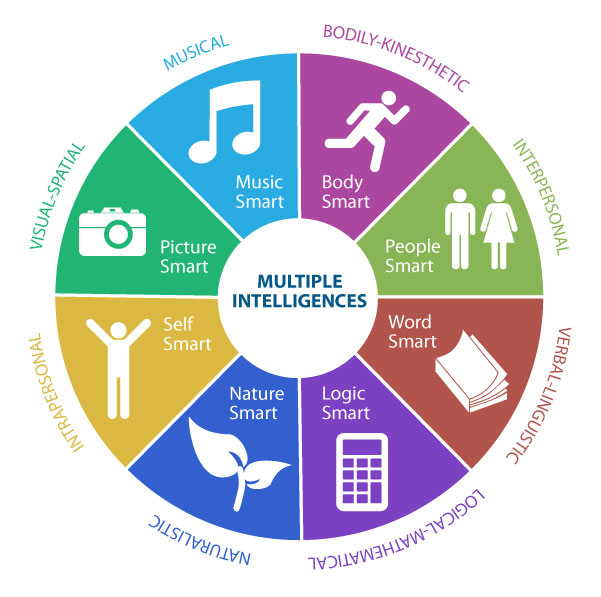

A popular framework is Multiple Intelligences, based on research by Howard Gardner. Gardner proposed that there are eight different ways of learning, creating things, and solving problems. Everyone uses all eight of these intelligences; however, in each individual, some intelligences are areas of strength, while others are weaker, leading to different preferences in learning. The eight multiple intelligences are:

Here is a more detailed description of the different intelligences:

| Intelligence | Description |

|---|---|

| “Word smart” Verbal-Linguistic Intelligence | The capacity to use language to express what’s on your mind and to understand other people. People who are high in this intelligence are sensitive to language, meanings, and the relationship of words. They engage easily with vocabulary activities, grammar, poetry, essays and plays. |

| “Logic smart” Logical-Mathematical Intelligence | People with a highly developed logical-mathematical intelligence understand the underlying principles of some kind of a causal system; or can manipulate numbers, quantities, and operations. Abstract thinking, counting, organizing; and logical structures are preferred by people high in this intelligence. They also like critical thinking activities, breaking words into smaller parts and reassembling them. |

| “Picture smart” Visual-Spatial Intelligence | People strong in this intelligence have the ability to represent the spatial world internally in their minds. Spatial intelligence can be used in the arts or in the trades and sciences. Those who are spatially intelligent and oriented toward the arts, are more likely to become painters or sculptors or architects than, say, musicians or writers. These people tend to be keen observers, able to think in three dimensions, and like to use metaphors. Learning materials that work well for them include: graphs, charts, colour codes, guided imagery, pictures, posters, and mind maps. |

| “Body smart” Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence | Body smart people have the capacity to use their whole body or parts of their body –hands, fingers, arms – to solve a problem, make something, or put on some kind of a production. These people have good body control and fine motor skills; and are often active and animated. They need “hands-on” learning opportunities, like shop, labs, games, skits, and plays. |

| “Music smart” Musical Intelligence | Music smart people have the capacity to think in music, to be able to hear patterns, recognize them, remember them, and perhaps manipulate them. People who have a strong musical intelligence don’t just remember music easily – they can’t get it out of their minds, it’s so omnipresent. People will be sensitive to rhythm, pitch, intonation, and can remember tunes and rhythms easily. They tend to like poems, plays, jazz chants, rap music, songs, and musically guided imagery. |

| “People smart” Interpersonal Intelligence | Those who are people smart have an understanding of other people. Anybody who deals with people has to be skilled in the interpersonal sphere. This is a social intelligence and those who are high in this area are outgoing and interactive; sensitive to others’ moods, feelings, and motivations. |

| “Self smart” Intrapersonal Intelligence | Self smart people have an understanding of themselves, of knowing who they are, what they can do, what they want to do, how they react to things, which things to avoid, and which things to gravitate toward. They tend to know what they can do. They tend to know what they can’t do, and they also tend to know where to go if they need help. |

| “Nature smart” Naturalistic Intelligence | Nature smart people have the ability to discriminate among living things (plants, animals), sensitivity to other features of the natural world (clouds, rock configurations) as well as a good sense of their surroundings and environment. They are also sensitive to changes around them, both outdoors and indoors. |

| Gardner later added a 9th intelligence: “Life Smart” Existential Intelligence

| People with existential intelligence have the sensitivity and capacity to tackle deep questions about human existence, such as the meaning of life, the reason for death, and the explanation of how we got here. They tend to be reflective, deep-thinking, and able to design abstract theories. They appreciate multiple perspectives, see connections, challenge assumptions, and push boundaries. They can become scientists, philosophers, and theologians. |

It is also important to note that we can continue to develop our intelligence, and use multiple intelligences to learn content in any course. Our brains continue to grow and develop over time, even into adulthood. Taking full advantage of these opportunities for growth can support learning in any course.

Exercise: Multiple Intelligences

Go to Howard GardnerL Multiple Intelligences Test and scroll down to the link for “free Multiple Intelligences test (based on Howard Gardner’s model)—in Microsoft Excel self-calculating format, and other versions.” You need Microsoft Excel on your computer to take this free online assessment of your preferred multiple intelligences learning styles.

Clicking the link will download an Excel spreadsheet with 74 questions. Answer each as directed on the 1 to 4 scale. Your score totals are then shown for each of the “multiple intelligences” learning styles.

OR

Use this assessment to discover your intelligence strengths:

Multiple Intelligences Self-Assessment Quiz

The multiple intelligences approach recognizes that different people have different ways, or combinations of ways, of relating to the world. Here is an example of visual-spatial intelligence, as an artistic, autistic savant draws the New York City skyline from memory.

Video: “Stephen Wiltshire draws NYC for UBS” (length 3:49)

A popular approach to learning styles is called the VARK approach Fleming, N.D. (1996). Teaching and Learning Styles: VARK Strategies. Hershey, PA: IGI Global., which focuses on learning through different senses (Visual, Aural, Reading/Writing, and Kinesthetic):

You can take a free, self-scored online assessment of your VARK learning style at VARK Learning Styles Questionnaire [PDF].

Once you discover the differences in learning styles and how they pertain to you, it may help you to shed light on your own learning habits and preferences, and give you ideas for incorporating other strategies. You shouldn’t conclude that you are one type of learner or another and that you should just focus your learning on using your preferred learning style as previously thought. It can be hard to break study habits which have formed over many years. However, by incorporating different modalities in your learning, you are more likely to remember and understand. Think of it as having a toolbox of ways to think and learn, and for each task, ask yourself which tool is the best one for the job.

There are many systems used by educators to describe the various ways in which people learn. These systems can help you learn more about how you as an individual person and post-secondary student learn – both in your current study strategies and in how you could enhance your learning by including other less familiar strategies. Feel free to research this further on your own.

Exercise: VARK Learning Styles

Some learning preferences are determined by culture and practice. Certain cultures or groups have specific ways of learning that differ from traditional Western practices. Indigenous learning, for example, often uses story-telling to demonstrate concepts. Stories are passed down from generation to generation, using elders to teach the younger ones. Learning in this manner incorporates social aspects, feelings of safety, and a familiarity for Indigenous learners.

Exercise: Cultural or Group Learning Preferences

Think about whether there are certain styles of learning, whether it be because of your culture, race, religion, association, or other group, that has influenced your style of learning. What practices are familiar to you? What practices help you learn better?

Learning preferences come in many forms. Whatever learning model you consider, you should pay attention to what works for you (and what doesn’t) and organize your study sessions accordingly.

Everyone faces challenges in learning at different times and to different degrees. There are many factors that will affect people’s ability to learn. Some are circumstantial (e.g. parenting young children) or environmental (e.g. adapting to a new culture) while others are self-inflicted (e.g. consistently staying up too late), and yet others are barriers that are more challenging to deal with (e.g. learning disabilities). Some are perceived (e.g. confidence). Other challenges for students include: fighting addictions, poverty, abuse, unsupportive partners, grief, discrimination, harassment, and chronic health issues. Whatever the challenge, there are strategies to help you through. It’s different for everyone, but you are definitely not the only student who is dealing with significant challenges. It’s important to identify your own personal learning challenges so that you can identify strategies to overcome them.

Challenges can be inherent in institutions. If things like racism, discrimination, harassment, inclusion, sexual violence, or gender bias are impacting students, they may be struggling with emotional or mental health issues. They may be struggling with feeling safe, feeling respected and valued, being understood, or being accepted. Often students are not aware of how systemic challenges can impede their learning. These kinds of repetitive stressors can cause ongoing problems with memory, retention, and focus.

Most colleges and universities have very well defined policies for discrimination, harassment, and sexual violence. Though the policies exist, it doesn’t mean that the practices and procedures line up with the policies. Often people are unaware of how certain practices can enhance discrimination, for example. If you are being impacted by any of these factors, ask about specified contact people in the school to have a private conversation with. You will be able to learn about your rights and options in a confidential setting, and then you can make an informed decision regarding what steps, if any, you choose to take.

The idea of “accessibility” is an important force of change on college campuses today. Accessibility is about making education accessible to all, and it’s particularly focused on providing educational support to a diverse group of students, faculty, and staff with disabilities. Colleges offer support for those with permanent disabilities (and some temporary disabilities) such as:

Those with documented disabilities have special legal rights to certain accommodations. Even those whose disabilities are not diagnosed can receive some accommodations. Accommodations may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Assistive technologies and web-accessibility accommodations are critical in today’s technology-driven economy and society. The following are some examples of assistive technologies:

Students in the following video share some of their experiences with the web accessibility.

Video: “Experiences of Students with Disabilities” (length 1:59)

For more information about web accessibility, visit WebAIM (Web Accessibility In Mind).

See the Supporting Students with Disabilities in B.C. Postsecondary Course website.

Most colleges and universities have accessibility coordinators (formerly called disability coordinators). If you know or suspect that you have a learning disability or if you have had significant learning challenges in the past, it would be a good idea to make an appointment with the accessibility coordinator in your institution. It’s best to do this well ahead of starting your program. Often it takes time to do assessments, apply for funding, apply for adaptive equipment or resources, and to develop an educational strategy that will work for you. Of course, you can make an appointment at any time in your program, but sooner rather than later is always a good plan.

Key Takeaways

Facing learning differences and challenges include:

Exercise: Learning Differences and Challenges

Think about the challenges discussed in this chapter, and brainstorm others that may impact you.

It’s good to understand learning styles, however just knowing your preference, however, doesn’t automatically provide a solution for how to do your best in your courses. For example, although you may be a kinesthetic learner, you’ll likely still have textbook assignments (reading) as well as lecture classes (listening). All students need to adapt to other ways of learning.

The following sections look at the key ways in which learning occurs in college classes and offer some suggestions about how to adapt your strengths for success.

Reading skills are critically important for adult students. Most classes involve reading assignments. Although many instructors may cover some of the textbook’s content in lectures or class discussions, students cannot skip the reading assignments and expect to do well.

If your personal learning preference is linguistic and independent—that is, if you learn well by sitting alone and reading—then you will likely not have difficulty with your university reading. Here are some tips to help maximize your learning:

If you have a different learning style, then you may need to give more attention to your reading skills. Always allow plenty of time for reading assignments—rushing makes it harder to understand what you are reading. Do your reading at times of the day when you are most alert. Find a quiet, comfortable place conducive to reading.

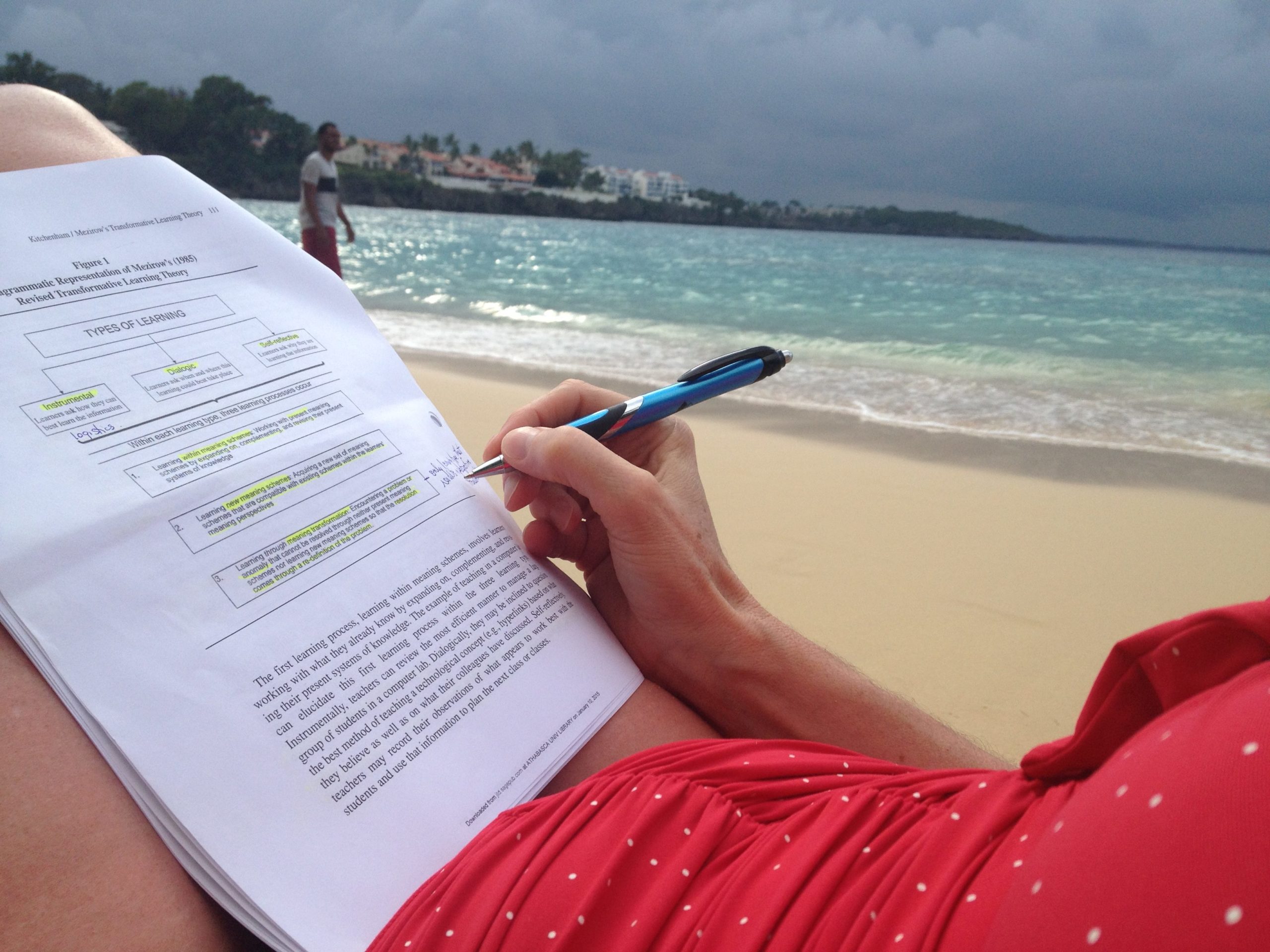

Try also to maximize your learning through your personal preference. If you learn better by listening, for example, sit up front in lecture classes where you can see and hear the instructor better. If needed, ask if you can record an instructor’s lectures and then listen again at a convenient time, such as when commuting to class or work, or while doing the laundry. If you are more of a visual learner, sit in class where you can see PowerPoint slides and other visual presentations most clearly. Use a visual approach in your class notes, as described in Module 5.6 “Study Skills: Note-Taking.” Check out whether video podcasts may be available for reviewing lectures. Try to relate all of these visual images to the textbook’s content when you’re reading an assignment. In addition, pay special attention to illustrations and diagrams in the book, which will further help you understand the written ideas and information. If you are more of an interpersonal learner, form a study group with other students and talk with others about the course topics. Take advantage of your instructors’ office hours to help clarify your understanding after reading assignments.

Listening skills are as important as reading skills. Students are expected to listen to their instructors in class and remember and understand what is said. In discussion classes, listening is important also for participating well in discussions.

If you favour listening, then you may already be good at understanding class lectures. Chapter 5 “Study Skills” provides tips to help you pay close attention, take good notes, and recall the information and ideas you have heard. Here are some more tips:

A “seeing” learner learns more effectively through seeing than through reading or listening. Some courses include demonstrations and physical processes that can be observed. If you are a visual learner, work on developing your reading and listening skills, too, because you will need to learn in these ways as well. Here are some tips to improve learning related to seeing:

People who learn best by doing are often attracted to careers with a strong physical or hands-on component, which can vary from athletics to technologies and trades. But these students may need to use other learning skills as well. Here are some tips to help maximize your learning related to doing:

Feeling learners focus on the emotional side of information and learn through personal connections. Too often they may feel that a textbook or a class is “dry” or “boring” if it focuses exclusively on written information. In addition to improving their reading and listening skills, students with this style can enrich their learning by focusing on what they and others feel about the information and ideas being learned. Here are some tips to help maximize your learning related to feeling:

Many classes tend to be taught using certain learning styles. Instructors in large lecture classes, for example, generally emphasize listening carefully and reading well. Don’t worry, however, if these are not your particular strengths, for much of this book focuses on learning study skills. Take responsibility for your own learning, rather than expecting the instructor to help you through the subject in your own personal way. For example, if your strength is as a visual learner but your instructor simply stands at a podium and lectures, then provide your own visual stimulation by sketching concept maps in your notes or by visualizing how information being presented might look in a pie chart or graph.

As you move further into your curriculum, you will likely have more small classes with class discussions, demonstrations, group presentations, and other learning activities. Once you are in classes closely related to a career path that interests you, you will find your personal style more relevant to the kinds of material you will be learning.

Much learning in college and university also comes from interactions with others, who often have different learning preferences. Be open to interacting with other students and instructors who are different from you, and you will find yourself learning in ways that may be new to you.

Exercise: Learning Preferences

This chapter dealt with the fact that all learners are facing different situations in learning. Some seem to learn easily – immediately grasping new concepts – while others have to work extremely hard to get good grades, and others seem to struggle regardless. This chapter examines the reasons that there are differences in learning, including learner strengths, preferences, challenges, circumstances, or learning disabilities.

Once learners recognize their own strengths and challenges, they can accommodate them by using different strategies.

Key Takeaways

Exercise: Learning Experiences

Summarize what you have learned about your own learning preferences and challenges. In light of these, what are some things you can do to make your learning experience more successful?

Let’s face it: being a student can be stressful! However, there are numerous supports available to students to aid along the way. Some are personal supporters who have been part of your network all along, and some are built in systems at colleges and universities. All too often, students don’t realize the number of supports available to them until things reach crisis conditions. In this chapter, you will identify supports that you may need so that you can utilize them throughout your educational journey.

Learning Objectives

In this chapter on “Support and Resources,” students will:

No one can do it alone. We aren’t meant to. We are designed to be in relationships, and it is these relationships which will give us the courage and strength to forge ahead in our lives. Support can come in many ways. Personal supports come in the personal relationships in our lives through family, friends, and connections.

As well as personal supports, your support network should also include your community. Community is the group of people you associate with. It could be a group of people in the place you live (your neighbourhood) or at work, or a group of people you associate with through an activity. It could be a sports team, a club, a volunteer group, a church, or a parents’ group. It could be an exercise group, or a pottery club, or a music group. We all cherish a sense of belonging. Having a community of support for various aspects of our lives is meaningful. When you make the decision to go to college or university, you may be surprised by those within these communities who step up and show support. Note who they are. They may become invaluable supporters as you go through school.

Author’s Story

This women’s soccer team is an incredible group of women. They are competitive and love to work hard on the field. They love the exercise, the outdoors, the travelling, and meeting new players. But above all, this soccer team values the time spent together with each other, people they care about and can relate to. This group of women supports each other and often say they keep playing because of the friendship amongst the team members.

— Mary Shier, author of this textbook

Exercise: Identify Your Personal Support Network

Besides natural communities, there are organized formal support groups which can target issues in our lives. Alcohol and drug counselling, addictions support groups, weight control groups, cancer support groups, or mental health groups all bring together people with similar issues. Some support resources that exist in many communities include: crisis hot lines, counselling, women’s centres, employment centres, food banks, and many more.

Exercise: Community Supports

Research the community supports in your own community and note any resources that might be useful to you. Add these community resources as potential supports to your personal support network list above.

Going to college or university can be an adjustment and a time of transition. Hopefully you have people in your personal life who support you in various ways. Did you know that colleges and universities also support students in many different ways?