Book Cover

1

1

Active Bystander Intervention: Training and Facilitation Guide by Sexual Violence Training Development Team is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

© 2021 Sexual Violence Training Development Team

Active Bystander Intervention Training and Facilitator Guide: Preventing and Responding to Sexual Violence in BC Post-Secondary Institutions is an adaptation of Active Bystander Training May 2020 and Bystander Intervention January 2020 by Simon Fraser University. It was shared under a Memorandum of Understanding with BCcampus to be adapted as an open education resource (OER) for the B.C. post-secondary education sector.

The Creative Commons licence permits you to retain, reuse, copy, redistribute, and revise this book—in whole or in part—for free providing the author is attributed as follows:

If you redistribute all or part of this book, it is recommended the following statement be added to the copyright page so readers can access the original book at no cost:

Sample APA-style citation:

This resource can be referenced in APA citation style (7th edition), as follows:

Cover image attribution:

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-77420-106-0

Print ISBN: 978-1-77420-107-7

This resource is a result of the BCcampus Sexual Violence and Misconduct (SVM) Training and Resources Project funded by the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training (AEST).

2

The web version of Active Bystander Intervention Training and Facilitator Guide: Preventing and Responding to Sexual Violence in B.C. Post-Secondary Institutions has been designed with accessibility in mind by incorporating the following features:

In addition to the web version, this book is available in a number of file formats including PDF, EPUB (for eReaders), MOBI (for Kindles), and various editable files. Here is a link to where you can download the guide in another format. Look for the “Download this book” drop-down menu to select the file type you want.

While we strive to ensure that this resource is as accessible and usable as possible, we might not always get it right. Any issues we identify will be listed below.

There are currently no known issues.

The web version of this resource has been designed to meet Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0, level AA. In addition, it follows all guidelines in Accessibility Toolkit: Checklist for Accessibility. The development of this toolkit involved working with students with various print disabilities who provided their personal perspectives and helped test the content.

If you have problems accessing this resource, please contact us to let us know so we can fix the issue.

Please include the following information:

You can contact us one of the following ways:

This statement was last updated on May 14, 2021.

3

Active Bystander Intervention Training and Facilitator Guide: Preventing and Responding to Sexual Violence in B.C. Post-Secondary Institutions was collaboratively created as part of the BCcampus Sexual Violence and Misconduct (SVM) Training and Resources Project. The project was led by BCcampus and a working group of students, staff and faculty from B.C. post-secondary institutions. It was funded by the BC Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training (AEST).

This guide is an adaptation of Active Bystander Training May 2020 and Bystander Intervention January 2020 by Simon Fraser University, which was shared under a Memorandum of Understanding with BCcampus to be adapted as an open education resource (OER) for the B.C. post-secondary education sector.

This adaptation is © 2021 by the Sexual Violence Training Development Team and is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License, except where otherwise noted.

The enhancements made to this resource were informed by the Evaluating Sexualized Violence Training and Resources: A Toolkit for B.C. Post-Secondary Institutions developed by the Sexual Violence Training and Resources working group.

4

The authors and contributors who worked on this resource are dispersed throughout BC and Canada and they wish to acknowledge the following traditional, ancestral and unceded territories where they met online and worked together, including K’ómoks First Nation in Comox Valley, BC; Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱SÁNEĆ territories in Victoria, BC; xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) territories in Vancouver, BC; Syilx Okanagan Territory in Kelowna BC; the Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc Territory in Kamloops, BC; Ktunaxa, Syilx (Okanagan), and Sinixt territories in the West Kootenays, BC; Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples in Toronto, ON. We honour the traditional knowledge and ways of knowing and being of the peoples of these territories. Their knowledge has existed in these spaces since time began.

Active Bystander Intervention Training and Facilitator Guide: Preventing and Responding to Sexual Violence in BC Post-Secondary Institutions was a collaboration between the public post-secondary institutions of British Columbia, BCcampus, and the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training as part of the Sexual Violence and Misconduct (SVM) Training and Resources Project.

We would like to thank the Sexual Violence Training and Resources Working Group for their leadership, dedication, and passion for this project over the past two years.

We would like to thank all the Sexual Violence Training Development Team who worked hard to create content and enhance this training to ensure these resources reflect the core principles in the SVM Evaluation Toolkit.

We would like to thank all the BC post-secondary institutions, student associations, and community organizations who shared their training to be evaluated as part of Phase One for this Project. We would also like to thank DKS Consulting for their work on evaluating the SVM training in BC.

We would like to thank Thompson Rivers University, the University of British Columbia Okanagan, AMS Student Society of UBC Vancouver; Sexual Assault Support Centre, and Simon Fraser University for the sharing of their SVM training resources for this project.

5

This resource was developed as part of a provincial project to develop open access resources to address sexual violence and misconduct at post-secondary institutions.

Active Bystander Intervention Training and Facilitator Guide: Preventing and Responding to Sexual Violence in B.C. Post-Secondary Institutions is one of four open educational resources now available for the B.C. post-secondary sector. These four components can serve as a foundation for a comprehensive educational strategy to provide students, faculty, and staff with the awareness, knowledge, and skills required to prevent and respond to sexual violence and misconduct and to create healthier and safer campuses for all.

| Training | Audience | Delivery | Length | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accountability and Repairing Relationships | Individuals who have been informed that they have caused harm in the context of sexual violence | One-on-one or small group facilitation | Four 60-90 minute sessions (minimum) | A series of educational sessions that guides learners through information and reflection activities that help them recognize the harm they have caused, learn how to be accountable, and develop the skills needed to build better relationships and support a safe and healthy campus. |

| Active Bystander Intervention | All faculty, students, and staff | Workshop | One 90 minute session | A workshop that focuses on the knowledge and skills needed to recognize and intervene in an incident of sexual violence. Uses the 4D’s Active Bystander Intervention Model. |

| Consent and Sexual Violence | All faculty, students, and staff | Workshop | One 90 minute session | A workshop that explores different understandings of consent, including the legal definition. Learners have the opportunity to develop skills related to asking for and giving consent in all relationships as well as discuss strategies for creating a “culture of consent” in campus communities. |

| Supporting Survivors | All faculty, students, and staff | Workshop | One 90 minute session | A workshop that helps learners respond supportively and effectively to disclosures of sexual violence. Includes a discussion of available supports and resources, the difference between disclosing and. reporting, and opportunities to practice skills for responding to disclosures. Uses the Listen, Believe, Support model. |

In 2016, the B.C. Sexual Violence and Misconduct Policy Act was introduced, requiring all 25 B.C. public post-secondary institutions to develop policies to prevent and respond to sexual violence and misconduct. In 2017–2018, a government outreach campaign identified the need to increase access to quality training resources. While access to training resources is an issue for all institutions, it is a particular challenge for smaller institutions. The need for open access educational resources that could be adapted by individual post-secondary institutions was identified as an important part of increasing knowledge about sexual violence and system-level capacity building (BCcampus, 2019).

In 2019, a cross-sectoral sexual violence and misconduct training and resources working group was established to provide advice and identify priorities for the development of the resources. Over a two year period, the Working Group:

This training is part of a growing collection of open education resources for addressing sexual violence in BC. These resources are intended to be of use for staff, students, and faculty working in a range of contexts, including:

How This Resource Was Developed

The resources for this project were developed, written, and reviewed collaboratively by a development team which included individuals with expertise in a wide range of areas, including sexual violence prevention and response, trauma-informed practice, adult education, equity and inclusion, Indigenous education, and community-based anti-violence programming and service delivery. Members of the Sexual Violence Training and Resources Working Group also reviewed the materials and provided feedback on how to tailor the materials to the post-secondary context.

Content specific to Indigenous considerations, working with international students, and gender & LGBTQ2SIA+ inclusion was reviewed and/or written by individuals with extensive experience in these areas. However, it is important to remember that these are areas where best practices are rapidly emerging and changing. We highly recommend that this resource be used as an introduction and foundation for addressing these topics in your work. As you adapt this training for your particular context, it is important to continue to build on the expertise and knowledge of students, staff, and faculty with experience in these areas and to develop an approach to training that reflects current issues, needs, language, and perspectives of these diverse groups within your institution and/or community.

This resource includes two components:

This resource is licensed under a Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0 License) which means that you are free to share (copy, distribute, and transmit) and remix (adapt) this resource providing that you provide attribution to the original content creators. You can provide credit by using the attribution statement below.

Active Bystander Intervention Training and Facilitator Guide: Preventing and Responding to Sexual Violence in B.C. Post-Secondary Institutions, Sexual Violence Training Development Team is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

In December 2019, a Working Group of experts in the field of sexual violence met to discuss the development of sexual violence training and resources at post-secondary institutions in BC. The group included staff, students and faculty actively involved in sexual violence prevention and response activities at their respective institutions. Following the meeting, the Working Group met through an online community of practice to identify key principles central to development of training on sexual violence. These eight key principles have guided the development of this resource.

A full description of the principles can be found in Evaluating Sexualized Violence Training and Resources: A Toolkit for B.C. Post-Secondary Institutions (SVM Training and Resources Working Group, 2020).

I

1

The Sexual Violence and Misconduct Policy Act (2016) requires all B.C. public post-secondary institutions to have a sexual violence and misconduct policy. Institutions are required to review their policies at least every three years and to include consultation with students as part of the review.

As you prepare your training materials, you will want to make sure that you have the most up-to-date version of your institution’s policy. Every institution has different definitions of sexual violence and misconduct and you will want to revise the training materials to reflect this and include links to the policy in all resources.

If your institution does not have a plain language summary of the policy, you may want to collaborate with on-campus organizations to develop one. Within a campus community, English literacy levels will vary enormously. As well, an accessible policy helps to support victims and survivors of sexual violence in having control and autonomy over their options related to making a disclosure, making a report, and accessing supports, accommodations, and other resources.

As you prepare your training, you may want to learn more about your institution’s protocols and procedures related to sexual violence. These protocols and procedures will describe the roles and responsibilities of various departments, services, staff and faculty following a disclosure of sexual violence. It can be helpful to include some specific information about what happens following a disclosure in your training and/or to be able to respond to questions that learners might have.

You also may be designing and delivering your training for students, staff, faculty, and administrators who may be involved in responding to disclosures. You may want to ask about what kind of training they are interested in, e.g., online or in-person, length, “Level 1” or “Level 2.” You will also want to ensure that your training reaches individuals from different areas of the campus community.

Collaborating with groups and organizations on your campus and in the community can increase the accessibility and effectiveness of your training. Collaboration can lead to the development of new resources, opportunities for including the latest research and best practices on sexual violence prevention and response, and opportunities for co-hosting training and involving guest speakers (such as community support workers or Elders) and a greater diversity of facilitators. Some of the groups you might consider include:

Building relationships with a variety of student groups can be one of the most important ways of enhancing your training. This can include international students, students with disabilities, LGBTQ2SIA+ students, Indigenous students, graduate students, fraternities and sororities, and students involved in sex work. They will be able to provide perspectives on the issues that are important or relevant to them and provide guidance on issues such as inclusive language, when and where to hold trainings to increase participation, and barriers to accessing supports and services.

You will want to update any existing lists of resources and supports related to sexual violence. It is good practice to include both on-campus and community-based organizations, 24/7 supports as well as supports specific to various communities (e.g., LGBTQ2SIA+ people, multicultural groups). For information about community based anti-violence organizations, VictimLink B.C. (1-800-563-0808) is a good starting place as they will be able to connect you with organizations in your community.

Locating Community-Based Anti-Violence Programs and Services

VictimLink BC (1-800-563-0808) is a toll-free, BC-wide telephone help line, available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. It provides services in over 130 languages. It can be an important resource to include in learning materials. As well, the service can provide support in identifying programs and services in your community related to preventing and responding to sexual violence. They can help you identify crisis services (available in the evenings and on weekends) and learn about the referral criteria for specific groups and populations. For example, you will want to make sure that resource lists indicate whether a program is trans-inclusive or whether a multicultural program provides services for non-immigrants.

The Ending Violence Association of BC (EVA-BC) website provides information about Community-Based Victim Services, Stopping the Violence Counselling and Stopping the Violence/Multicultural Outreach Programs in BC.

2

Developing and delivering training on sexual violence can be an opportunity to build upon existing work at your institution toward Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation.

Acknowledging the traditional lands of the Indigenous people on which you live, work, and study is an important way to begin an event or meeting and can be included as part of classroom activities and taught to students. Meaningful territory acknowledgements allow you to develop a closer and deeper relationship with not only the land but the traditional stewards and peoples whose territory you reside, work, live, and prosper in.

Acknowledging the territory within the context of sexual violence training will open a person’s perspective to traditional ways of knowing and being, stepping out of an organizational structure and allowing you to delve into the person’s own perceptions, needs and abilities.

When we speak about sexual violence, we cannot do so without highlighting the direct connection to tactics used to colonize and assimilate the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island (North America). Sexual violence is intimately intertwined in Indigenous peoples ongoing traumas from colonization; from first contact in North America, to the horrific abuses perpetrated upon children in Residential Schools, the occupation of land and accessing of natural resources without consent, to the forced sterilization of Indigenous women, to the thousands of Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit people as victims of sexual or physical violence and death as highlighted by the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Commission of Canada.

Territory acknowledgements are designed as the very first step to reconciliation. What we do with the knowledge of whose traditional lands we are on is the next important step.

Some questions to consider as you acknowledge your territory:

Should your institution have an approved territory acknowledgement please use that to open the session(s); however, we invite you to consider how to make that institution statement more personal and specific to you, in that moment and in the work you are about to delve into with learners.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action explicitly state that each of us as members of Canadian society have a direct responsibility to contribute to reconciliation; how we discuss colonization in relation to sexual violence is a direct response to that responsibility.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is an international instrument adopted by the United Nations on September 13, 2007, to enshrine (according to Article 43) the rights that “constitute the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.” UNDRIP was adopted into the B.C. provincial legislature on November 26, 2019. Centering the history of colonization as a background and framework to sexual violence and misconduct both from a historical as well as current ongoing struggle is in direct response to our legal and moral obligation as members of Canadian society.

Indigenization is a process of naturalizing and valuing Indigenous knowledge systems (Antoine et al., 2018; Little Bear, 2009). In the context of post-secondary institutions, this involves bringing Indigenous knowledge and approaches together with Western knowledge systems. This benefits not only Indigenous learners but all students, staff, faculty and campus community members involved or impacted by Indigenization.

As you adapt this training for your particular context, consider how and in what ways you might interweave Indigenous content and approaches. Examples of how you might include an understanding of Indigenous ways of knowing and being:

As you do this work, as an Indigenous or non-Indigenous person, you will want to continue to draw upon and build on existing relationships with Indigenous people, both within and outside of your institution. As a way of continuing to work in intentional and respectful ways, you may want to reflect on questions such as:

Elders and Knowledge Keepers

Elders have always been the foundation for emotional, social, intellectual, physical and spiritual guidance for Indigenous communities. As you find ways to naturalize Indigenous context, perspectives and traditional ways of being into your training, we recommend you consider inviting an Elder or Knowledge Keeper from your local community to support your sessions. One way of doing this is to speak with your Indigenous Student Services Department at your institution and share with them some of the recommendations in this guide and see how they might wish to support this work.

Not all institutions will have an Elder-in-Residence but each should have ways for you to contract an Elder or Knowledge Keeper to come in and support your work. Elders and Knowledge Keepers often support the whole post-secondary institution community, not just the Indigenous students. Involving Elders and Knowledge Keepers can help support reconciliation by helping to build respectful, reciprocal relationships that are deep and meaningful.

Whenever you plan to bring in a community member, Elder, or Knowledge Keeper, it is important to plan for the honorarium required to remunerate them for their time and sharing their lifetime of wisdom and traditional teachings. In many communities, it is seen as most respectful to offer payment on par with what you would pay a Ph.D. holder to do a keynote presentation. However, consulting on this with the Indigenous Services staff at your institution on what is a typical amount for this type of event is also a good practice.

3

In 2018, there were nearly 500,000 international students in Canada at all levels of study which was an 17% increase from 2017 (Canadian Bureau for International Education, 2018). B.C. hosts the second largest international student population next to Ontario, followed by Quebec.

International students may be at significant increased risk of being targeted for sexual violence and may face unique barriers to reporting and accessing supports (see Section 2: International Students for more information about barriers). According to the B.C. International Student Survey, international students rely primarily on other international students from their home country and from other countries for their primary sources of support, especially for non-academic issues (Adamosky, 2015). Consequently, international students who are survivors of sexual assault will be more likely to disclose the sexual assault and gain support from other the international students. International students who experience or who are impacted by sexual violence are also significantly less likely to seek help from counselling services due to language barriers and cultural differences (Mori, 2000). To make matters more complex, cultural perspectives of violence and rape myths differ from one culture to another (Bonistall Postel, 2017). Thus, international students might have difficulty identifying sexual violence and responding to disclosures of sexual assault. Therefore, it is important for post-secondary institutions to play a role in equipping international students with basic understanding on how to best respond, support, and advocate for their peers in an appropriate and sensitive matter that does not further traumatize the survivor.

Post-secondary institutions should involve international students in the development and implementation of training on sexual violence. They are the experts and can identify the gaps and needs of their peer groups and as individuals. Facilitators can develop the training agenda based on their needs and be prepared with the relevant safety resources that include community organizations and groups, translated materials and supports. Post-secondary institutions can build partnerships with organizations that are providing support to international students who can share the collateral they have, e.g., safety booklets, infographics and educational materials (see, for example, the International Student Safety Guide developed by MOSAIC).

II

4

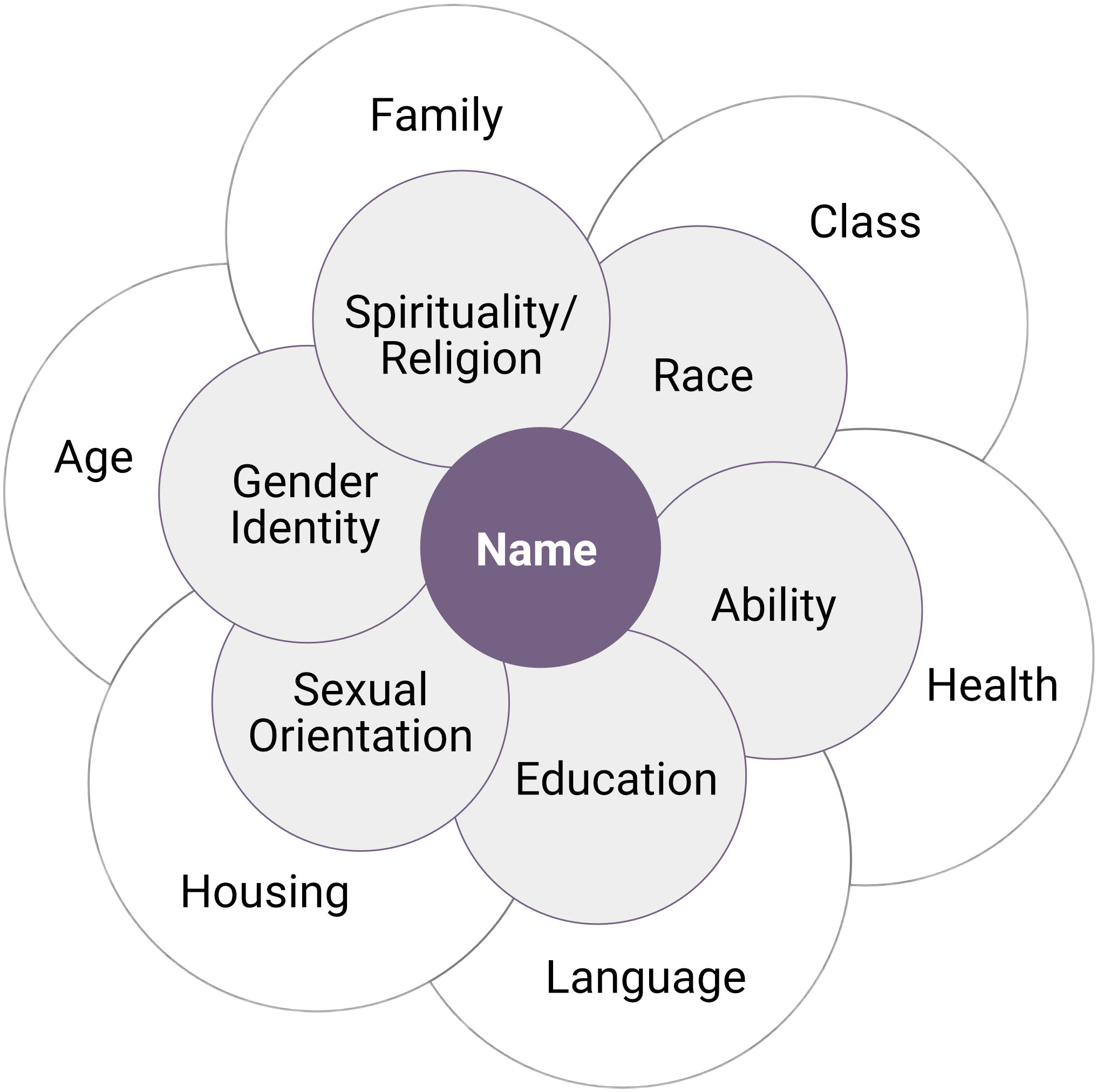

The term social location is often used by facilitators working in the anti-violence sector (Baker et al, 2015; Ontario Association of Interval and Transition Houses, 2018; Simpson, 2009). The concept of social location comes from the field of sociology and describes the groups that people belong to because of their place or position in society. An individual’s social location is defined by a combination of factors such as gender, race, social class, age, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographic location. This makes social location unique to each individual – no two individuals will have the exact same social location.

Social location is important because it strongly influences our identity, or our sense of self, and how we see the world. When it comes to the topic of sexual violence, we all have different experiences, values, beliefs, attitudes, strengths, and vulnerabilities. It can be helpful to try to understand your social location in order to be able to facilitate across all these differences. Here are some questions to help with that process:

To facilitate across difference means to be grounded in an awareness of your own social location. As a facilitator, you will want to recognize the diversity of social locations of your audience and to value the knowledge and experience learners bring with them. At a practical level, this understanding can help you raise issues related to sexual violence in a way that will create a safer space for all learners. An awareness of your own social location allows you to engage in conversations about how social location influences experiences of sexual violence and provides a foundation for unpacking assumptions, championing new ideas, and promoting values central to creating safer campuses.

Disclosing Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Your sexual orientation and gender identity are important points of reflection as a facilitator. If you can and feel safe doing so, disclosing your sexual orientation and gender identity in a way that is thoughtful and respectful may help in creating a safe space for gender and sexual minorities by signalling that you are aware of your social location. Be precise in your language, for example:

“I am a straight, cisgender woman who is neurodivergent and I am aware that the privileges and disadvantages associated with sexual orientation and gender identity mean that I experience the world in a very different way than some of you might.” is preferable to “I’m a woman.”

For examples of precise language relating to sexual orientation and gender identity, please see Section 2: Gender & LGBTQ2SIA+ Inclusive Language.

Individuals with a background in anti-violence work, human service work (i.e., social work, child and youth care), health services (i.e., nursing), or those that have experience and knowledge in issues related to social justice, criminology, and mental health are well suited to facilitating training on sexual violence. If resources are available, you will ideally want to have facilitators from a range of social locations deliver training related to sexual violence prevention and response. Having facilitators of diverse backgrounds is important in creating safe, inclusive, and welcoming learning environments for diverse learners.

For example, when delivering to student groups, a peer-to-peer facilitation model can help to increase credibility of the training as well as have other benefits such as empowerment of facilitators (Hines & Palm Reed, 2015; McMahon et al., 2013; McMahon et al., 2014; Turner & Shepard, 1999). Transgender, non-binary, Two-Spirit and other queer people benefit from learning about sex and sexual violence from facilitators who share their personal lived experiences and have developed an analysis of the negative impacts of systemic queerphobia on LGBTQ2SIA+ people.

With mixed audiences, whenever possible, co-facilitation teams should include people of differing social locations and experiences. For example, a transgender or non-binary facilitator could be paired with a cisgender/heterosexual facilitator. This is beneficial for two reasons: transgender, queer, and non-binary audiences may connect more and feel safer with a facilitator of similar lived experience and the other facilitator can carry the burden of diffusing problematic situations that may arise from (sometimes well-intentioned) queerphobic comments. In short, a pairing of non-queer and queer facilitators may create safe spaces for queer learners and facilitators (Rensburg & Smith, 2020). In general, a diversity of facilitators demonstrates that sexual violence is an issue relevant to people of all genders and social locations (Moynihan et al., 2012; Roy et al., 2013).

5

Accessibility typically refers to all the ways in which the training environment, delivery and participation options, and materials are designed to allow for people from a variety of backgrounds, abilities, and learning preferences to participate fully. Your institution will likely have policies, resources and supports related to accessibility that you can build on as you prepare to deliver training on sexual violence. Below is a list of strategies you may want to consider in order to make your training more accessible and inclusive.

Creative Approaches to Learning

Community-based and campus-based anti-violence programs and initiatives have a long history of developing innovative and creative approaches to support learners of all backgrounds. This resource provides suggestions on how to facilitate activities both in-person and online. It also includes suggestions of additional activities that help to explore and increase understanding of issues related to sexual violence such as power and privilege; the impact of colonialism on sexual violence; and ideas about gender roles and how they influence people’s experiences of dating and relationships. Depending on the learner(s), many of these topics can be abstract and difficult to engage with through discussion-based activities or in a single workshop. We encourage you to make connections, in-person or online, with anti-violence organizations or to consult anti-violence resources and toolkits to develop creative approaches to delivering this training. Below are a few suggestions of creative approaches to education on sexual violence prevention and response.

For sexual violence training to be successful, learners need to feel comfortable, safe, and respected. As you prepare to facilitate, you will want to consider factors such as when and where to hold the training, key messages on promotional materials, the use of group guidelines, ensuring diverse representation, using icebreakers, whether activities require self-disclosure, and ways of working with co-facilitators or guests. In this section, we discuss several strategies for helping to create a positive learning space.

Facilitators have an enormous role to play in setting the “tone” for a session. As people enter the space (online or in-person), you can welcome them and help them get oriented. You can let them know if you’ve started or whether you’re waiting for a few more people and share “housekeeping information” such as where the bathrooms are, where they can put their things, or how to use online interactive features. If the training will include interactive or discussion-based activities, you may want to consider using an icebreaker activity to help people get to know each other ahead of time. As you begin your session, you can use opening questions that help create inclusivity such as correct pronouns, check-in questions, or information about accessibility needs and requests.

Community or group guidelines are an activity that brings groups together to decide how they will interact and support each other. This process can take anywhere from a few minutes to 30 minutes. If you are facilitating a short training (e.g., a one-hour lunch time session) or a training in which learners may not be interacting extensively with each other, creating community guidelines may not make sense. Instead, you might ask learners to agree to a list of guidelines or a code of conduct when they register or sign-up for the training. Or, you might share a list of guidelines at the beginning of the training and ask learners if they feel comfortable with them and/or if they have something they would like to add or change.

For longer sessions (e.g., a three-hour workshop) or for training that involves multiple sessions over a period of time, community guidelines can be an important tool for supporting safer discussion about difficult topics. You can remind learners of the guidelines if the discussion is getting difficult or at the beginning of each session. Important group agreements relate to listening to and showing respect for others (e.g., not talking when others are speaking, not making rude comments, or not talking on the phone), confidentiality, and participation.

Examples of Community or Group Guidelines

Community guidelines come in all shapes and sizes. Some groups have a few guidelines while others have many. Often, groups will change or add guidelines as needs and ways of working together evolve. Here are suggestions of possible guidelines.

Content warnings (also called trigger warnings) are a statement made prior to sharing potentially difficult or challenging material. The intent of content warnings is to provide learners with the opportunity to prepare themselves emotionally for engaging with the topic or to make a choice to not participate.

Different departments and institutions will have different approaches to content warnings and this may guide your decision about including content warnings on registration or sign-up forms, in learning materials, and in the learning environment. Below is an example of a content warning:

“We will be discussing topics related to sexual violence in this training. During the training, you can choose not to participate in certain activities or discussion and can leave the room at any time. If you feel upset or overwhelmed, please know that there are resources to support you.”

There are a number of other facilitation strategies you may want to consider in addition to or instead of a content warning:

Inclusive language is important and helps avoid making assumptions about others. As a facilitator, you will want to use language that is inclusive of all people regardless of their sexual orientation, gender identity, sex assigned at birth, and marital or romantic status.

Because your audience is likely to be diverse, it’s important to be respectful of the many ways they experience gender, attraction, and relationships. Choose examples, scenarios, statistics, and images that are non-gendered or inclusive of LGBTQ2SIA+ people and relationships. Sexual violence is not exclusive; it can happen to and be perpetuated by people of diverse genders, sexes, and attractions.

If you are speaking in general terms, take care to choose terms like “intimate partner or partners” instead of “husband,” “wife,” “boyfriend” or “girlfriend.” If you are referring to a specific person’s intimate partner, use the same language they use. If a person refers to their intimate partner as their “spouse” or “wife,” you should use the word they do instead of referring to their “partner.”

Likewise, addressing learners using inclusive language will ensure a sense of safety for learners. For example, “Good afternoon, everyone,” “Hello, folks,” and “Have a good break, human beings” are inclusive of transgender, non-binary, Two Spirit, and gender diverse people while “Welcome, ladies and gentlemen” is exclusive. Similarly, avoid everyday gendered language (e.g. man hours, spokesman, and waitress should be replaced with work hours, spokesperson/speaker, and server) or historically oppressive turns of phrases such as “rule of thumb.” Try using language such as “someone of another gender” and “people of all genders” rather than “the opposite sex” or “both genders.”

Be careful to address or refer to people with similar titles in similar ways, regardless of their gender identity. If you refer to a cisgender male professor as “Dr. Last Name,” as a default, refer to all professors as “Dr. Last Name.”

Don’t assume pronouns, sexual orientation (attraction) or gender identity based on someone’s name or appearance. Invite all learners, guests, and co-facilitators to indicate their pronouns and their preferred name on their nametag or in their online display names, if they feel safe doing so. Explain that sharing our pronouns is a way to act in solidarity with some people who are gender diverse, transgender, non-binary, and Two Spirit people, but that, ultimately, it is a way to be inclusive of all people.

Examples of gender inclusive language:

Experiences of trauma and violence are common in our society. Many people participating in sexual violence training will have experiences of past or current trauma and many facilitators will have experiences of trauma themselves. There are a number of strategies you can use to help create a “trauma aware” learning space.

People who have experienced trauma may describe themselves as a “victim” or “survivor” or “victim/survivor” of trauma. These words have their own history and meanings. Language is imperfect and constantly evolving and there is no one best or “correct” word. Do your best to use the term that people prefer whether that be “victim” or “survivor” or something else entirely and don’t be afraid to respectfully ask if you are unsure.

Possible Signs of a Trauma Response

The following list may help you in recognizing and responding to ‘in-the-moment’ trauma responses.

(BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services, 2013)

As a facilitator, you will want to ensure that you are knowledgeable and prepared to address the distinct and specific needs of multicultural and diverse communities. International students are one group that you may want to consider. They may be at significant increased risk of being targeted for sexual violence, due to multiple barriers they face including lower levels of English language fluency, a lack of understanding of criminal law in Canada, cultural views of sexual violence, discrimination, racism, a need to adjust to local culture and limited local support systems (Forbes-Mewett and McCulloch, 2016). Furthermore, they may not understand the legal definitions of sexual violence and what consent means, and where to find help.

It is important to highlight that international students are not weak or vulnerable; rather they are quite resilient and determined to thrive and make Canada their home. It takes positive determination to leave the safety of family, financial stability and social network. However, once here, they may face the additional challenges from within their own ethno-specific community while also experiencing homesickness, loneliness and helplessness as part of their acculturation into Canadian society.

As a facilitator, there are a number of strategies you can take to ensure the inclusion and participation of international students:

“Challenges Faced by International Students” image description

An infographic with the following text:

International students have to navigate a new country on their own and face unique barriers and complexities compared to domestic students, especially when it comes to sexual violence.

End of image description. [Return to place in text]

6

Intersectionality is a concept that promotes an understanding of people as shaped by the interactions of different social locations or categories ― for example, race, ethnicity, Indigeneity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, age, ability, migration status, and religion.

In the context of sexual violence, intersectionality can help increase understanding of how certain populations face increased risks of perpetrating sexual violence and others face increased risks of being targeted by sexual violence. It also highlights how different groups of people experience systemic barriers to disclosing and accessing support services. It can also help ensure that responses to sexual violence are attentive to and reflective of the diversity of campus communities.

Activity: Power Flower

The Power Flower is a visual tool that we can use to explore how our multiple identities combine to create the person we are.

Instructions:

Feel free to customize this list to your audience and the focus of your training.

This Power Flower activity is adapted from: Arnold, R., Burke, B., James, C., Martin, D., and Thomas, B. (1991). Educating for Change. Toronto: Between the Lines. Available from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED336628.pdf

This Power Flower activity is adapted from: Arnold, R., Burke, B., James, C., Martin, D., and Thomas, B. (1991). Educating for Change [PDF]. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Download the Power Flower Activity here: Handout Power Flower Activity [Word file].

Because of the power inherent in sex and gender dynamics and the role they play in our lives, addressing sex, gender, and gender identity in discussions about sexual violence is essential. Gender can be a complex topic to discuss as there are many elements to consider such as identity, expression, orientation, and sex. Western understandings of sex, gender and gender identity have evolved from a binary view (two options: male and female) to a spectrum which suggests there are multiple sexes (male, female, intersex), many gender identities, and a wide range of gender expressions that may or may not conform to societal expectations. Many cultures have respect and recognition for more than two sexes, genders or gender identities. This is true not only abroad, but among many nations Indigenous to Turtle Island (North America).

Sex: Biological factors used to describe physiological differences such as gene expression, chromosomes, genitals, and hormones.

Gender: The social roles, expectations, and behaviours that are prescribed to us based on our sex assigned at birth. This can be different between cultures and time.

Gender Identity: Our internal understanding of our own gender. It may or may not match what is outwardly apparent to others or what is expected of us by society.

As a facilitator, you will want to be familiar with key terms used to discuss gender. These terms are continuing to evolve and it is important to refer to people using their own terms.

| Cisgender | Refers to someone who identifies with the sex they were assigned at birth. Cis is a Latin prefix which means aligned with. |

|---|---|

| Transgender | Refers to someone whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. Trans is a Latin prefix which means across, beyond or through. (Note: use transgender and not transgendered as the term transgendered is outdated and seen as derogatory). |

| Non-binary | Refers to someone who identifies as having a gender outside of the male/female binary. |

| Two-Spirit | Refers to a specific identity held by some people Indigenous to Turtle Island (North America). Two-Spirit people may embody diverse sexualities, genders, gender expressions, and gender roles than those prescribed by colonial understandings of sex and gender. They often hold special cultural, spiritual, or ceremonial roles among their people. |

| Sex assigned at birth | Refers to the sex that an infant is assigned when they are born. It is based on the combination of hormones, chromosomes, and internal and external genitalia. The three most common options are female, male, and intersex. |

| Gender Identity | Refers to someone’s personal understanding of their gender. It may or may not align with their body and gender expression. |

Regularly Updated Language Resource

Inclusive language is continuing to evolve. Qmunity, BC’s Queer, Trans, and Two-Spirit Resource Centre has a resource called Queer Terminology from A to Q that is regularly updated.

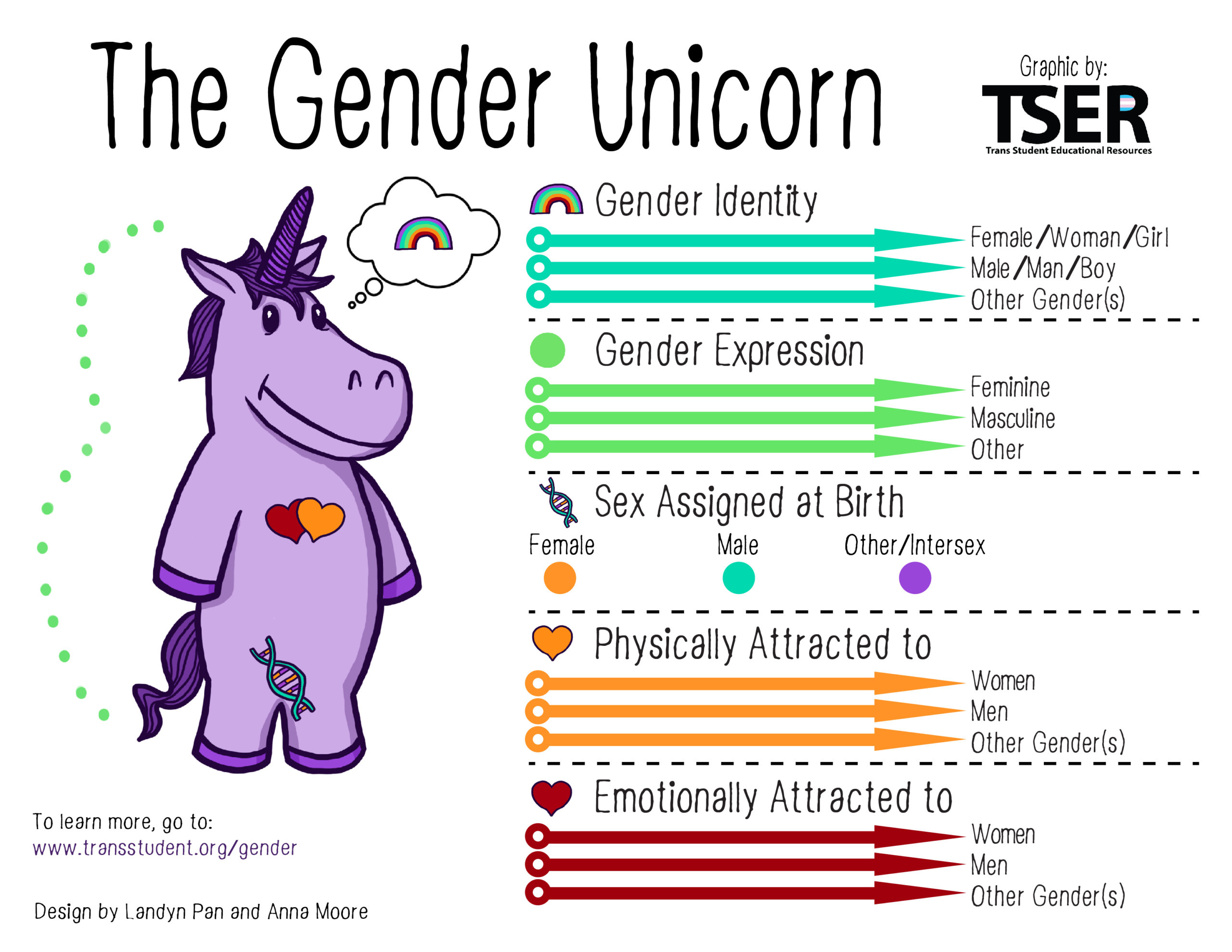

Activity: Gender Unicorn

The Gender Unicorn is a visual activity by Trans Student Educational Resources that allows learners to map out of their own experiences of sex and gender. It is available in an interactive form, as a colouring book, and in different languages. (It uses a Creative Commons license and can be shared as long as credit is given.)

There are many different theories and perspectives about what the causes of sexual violence in our society are. Discussions about ideas such as social constructions of gender roles, colonialism, enslavement, and patriarchy can help us to explore and understand the root causes of sexual violence and to collectively find answers and solutions.

Linking Sexual Violence and Gender Equity

Sexual violence is linked to gender inequities in society. The lives, bodies, agency, and work of women, girls, transgender people, and other gender diverse people are devalued while those of men are overvalued. Devaluing leads to dehumanizing and objectifying; overvaluing leads to entitlement and the misuse of power. Together this forms an environment where sexual violence perpetrated by men against women and people of diverse genders is normalized. One way to combat the pervasiveness of sexual violence is to ensure the norms, systems, and institutions in our society are equitable for people of all genders.

The term “rape culture” was first coined in the 1970s in the United States by second-wave feminists and the concept is often used in sexual violence prevention training in post-secondary institutions. Rape culture describes how sexual violence is common in our society and how it is normalized, condoned, excused, or encouraged. Examples of rape culture include the public tolerance of sexual harassment, the prevalence of sexual violence in media, the socialization of boys that promotes masculine identities based on notions of power and control, persistent discrimination against women and other equity-seeking communities, and the scrutiny given to the sexual histories of victims of sexual violence (Baker, 2014; EVA-BC, 2016).

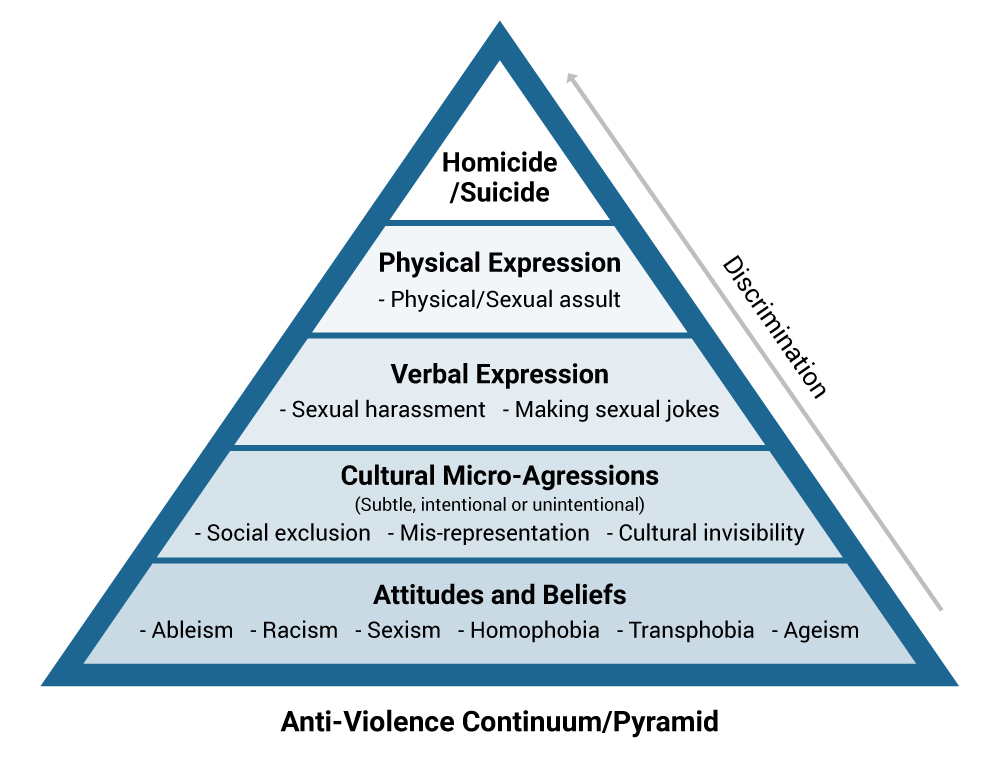

Many aspects of rape culture are often conceptualized as a continuum or pyramid or can be connected to other forms of violence in society.

Colonialism occurs when a group of people take control of other lands, regions, or territories outside of their own by turning those other lands, regions, or territories into a colony.

Colonialism remains embedded in the legal, political and economic context of Canada today.

Sexual violence and colonialism are interconnected through concepts such as self-determination, autonomy and consent. As well, many social norms in Canada are founded on colonial beliefs which are rooted in white patriarchal supremacy and which have created systems that support individuals, predominantly white men, to positions of power. These norms provide an illusion that people are entitled to what others have, including lands, cultures, and people’s bodies and that force is an acceptable way to claim these things, regardless of the harm to others (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019; Turpel-Lafond, 2020; Women’s Earth Alliance and Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016). An understanding of past and ongoing colonial violence can help provide context to issues such as why many Indigenous people and communities experience high rates of sexual violence today and the potential systemic or historical barriers to Indigenous People reporting sexual violence when it occurs.

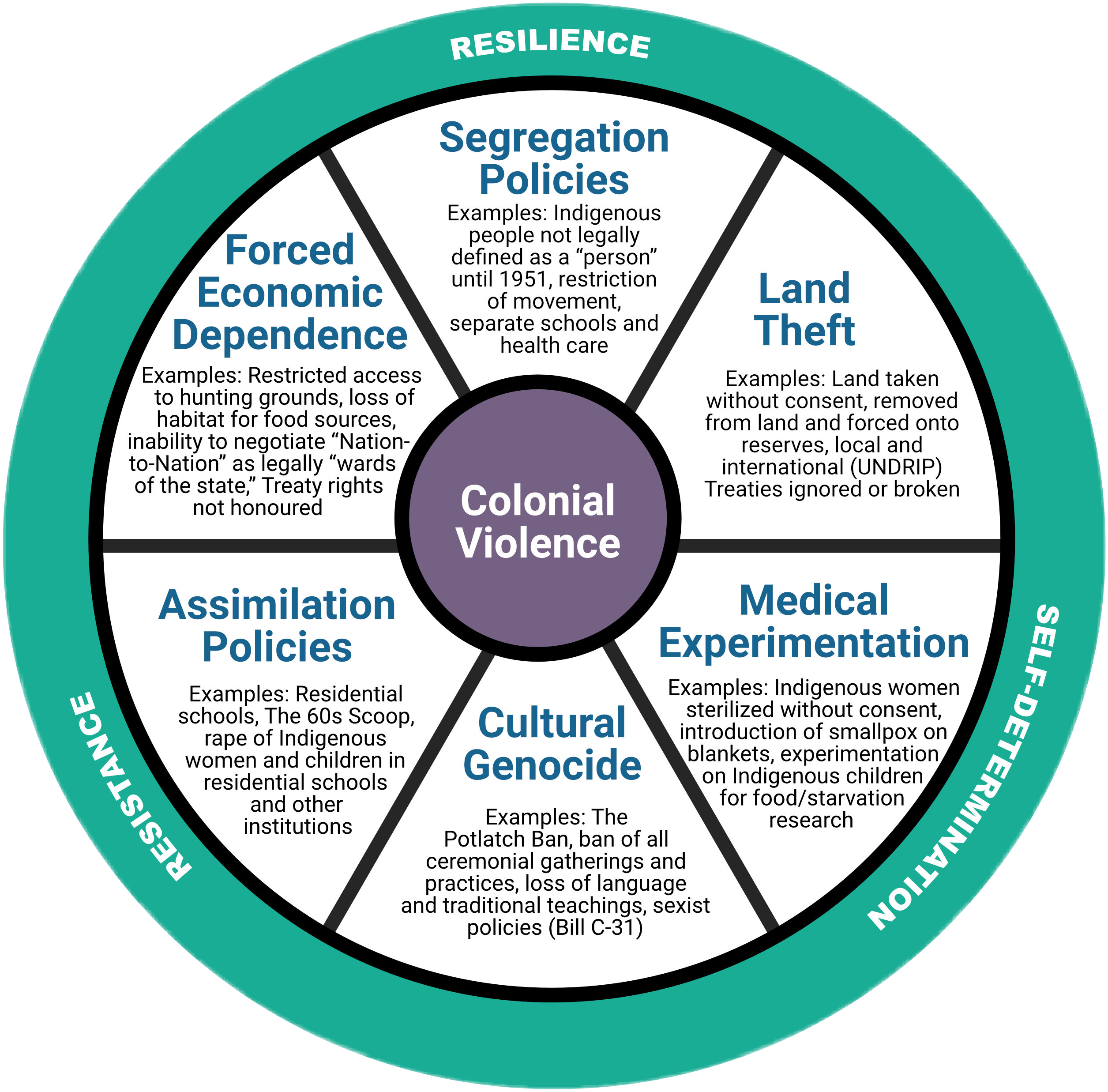

Activity: Colonial Violence Wheel

This Colonial Violence Wheel is a visual tool that can be used to help further discussion on the connections between colonial violence and sexual violence. Each section of the wheel provides examples of strategies, policies, and laws that have been enacted by the Canadian government to colonize and assimilate Indigenous people. Discussion questions can include:

Download the Colonial Violence Wheel Activity here: Handout Colonial Violence Wheel Activity [Word file].

“Healthy masculinity” and “toxic masculinity” are popular terms often used to explore beliefs, values, and stereotypes related to male identity and masculine norms in society. Masculine identity and norms are strongly linked with violence, with men and boys disproportionately likely both to perpetrate violent crimes and to die by homicide and suicide (Heilman and Barker, 2018).

Training on sexual violence on campuses will often explore ideas related to masculinity as a way of helping to shifting societal ideas about masculinity and to centre new values related to inclusivity and diversity. These conversations can help highlight how sexual violence harms people of all genders, including boys, men, and masculine people. It also can be an entry point for cisgender men to take a role in addressing sexual violence in their community.

Gender Unicorn image description.

A purple cartoon unicorn stands beside different ways to describe gender, sex, and attraction. They are as follows:

Anti-Violence Continuum/Pyramid image description.

A pyramid representing different aspects of rape culture. As you go to higher levels of the pyramid, the degree of discrimination increases. These are the levels of the pyramid from low to high:

Colonial Violence Wheel image description.

A wheel with the words “colonial violence” in the centre. Within each spoke of the wheel are examples of colonial violence. Surrounding the outer edge of the wheel are the words, “resilience,” “resistance,” and “self-determination.” Here are the examples of colonial violence:

7

Using questions is a simple way to deepen discussion and to promote critical thinking. We all make assumptions in order to arrive at opinions of how things are, what is important, and how things “should be.” Drawing out learner’s thoughts through the use of critical questions can help you to understand how to connect key concepts to learners’ personal experiences.

Key questions to encourage critical thinking could include:

You also can ask questions to help reframe an issue. For example:

There are many stereotypes, myths, and beliefs about sexual violence that do not reflect what research evidence tells us about sexual violence. There are many different approaches to responding to common myths during a discussion, including sharing statistics or research, asking a reflective question, clarifying definitions and concepts, or sharing an anecdote or experiential perspective. Below are some suggestions on how to respond to common myths about sexual violence (Sexual Violence and Prevention Response Office, 2020).

| Common Myths | Possible Responses |

|---|---|

| False reports

“People are lying or exaggerating when they talk about experiencing sexual violence.” |

“What are some reasons why people wouldn’t disclose? How are people usually treated when they say something? Do we really think people would lie knowing these barriers and potential responses?” “The number of false reports for sexual assault is very low, consistent with the number of false reports for other crimes in Canada.” |

| Clothing what a victim was wearing or doing

“If they’re dressing “that” way then they’re kind of asking for it.” “Why did she go there [party, hotel, nightclub]? |

“Nobody asks to be assaulted.” “Research has shown that outfits aren’t associated with assaults – there’s no kind of outfit that makes violence less likely.” “Consider if this response was applied to other crimes. For example, if your car was broken into and the police officers began questioning you about why you chose to park in a “bad” part of town. Does this sound fair?” |

| Ulterior motives

“Survivors are only looking for attention/status/money, or are acting out of regret.” |

“What kind of attention do survivors who come forward (especially publicly) typically get? Are they famous now?” “Do we really think people would rather face negative social responses than manage their own regret if that’s what happened?” “How might people’s desire to see the world as a good/safe place influence whether they believe survivors?” |

| Caution has gone too far

“People nowadays are too sensitive/overly politically correct/ anything can be construed as sexual violence.” |

“Who tends to be the person who is behaving ‘overly sensitive’? Who tends to be the other party?” “If you knew that something deeply hurt someone, why would you choose to continue anyways? What do you lose by ‘not doing the thing that causes harm’?” |

| Drinking alcohol or using other substances

“So, basically, you’re saying anyone who’s had sex while they were drunk has actually raped someone.” |

“The law says that in some situations a person may be affected by alcohol or drugs so much that they can’t give legal consent. When a person can’t give legal consent, any sexual activity with them is sexual assault. If you want to do something sexual with someone who’s been drinking alcohol or using drugs, you must be very careful that their thinking is clear. They must be able to decide freely if they want to be sexual with you and be able to communicate their consent clearly.” “If a person is unconscious or incapable of consenting due to the use of alcohol or drugs, he/she/they cannot legally give consent. Without consent, it is sexual assault.” “Alcohol is the number one drug used in drug-facilitated sexual assault.” “Some people who have been sexually assaulted blame themselves because they were drinking and might not describe what happened to them as sexual assault. If they didn’t consent, it is considered sexual assault.” |

| Assumptions about perpetrators

“But they’re such a nice person! I’ve never been uncomfortable around them.” “Different countries have different understanding so they just do it more.” “Most sexual assault is committed by strangers….usually outside in dark, dangerous places.” |

“About 80% of the time, the survivor knows the perpetrator. They can include dating partners, acquaintances, and common-law or married partners.” “Just because you have never experienced something with a person doesn’t mean others haven’t.” “We need to be careful with really broad generalizations about specific cultures. Perpetrators come from many different cultures and backgrounds. People from the same culture may hold very different values.” “The majority of sexual assaults happen in private spaces like a residence or private home.” |

Adapted from: Sexual Violence and Prevention Response Office. (2020). Bystander Intervention (Facilitation notes). Thompson River University. Used with permission.

While facilitating, you are likely to encounter challenging moments when you might not be sure how to respond, when you strongly disagree with the perspective of the learner, or when the conversation has shifted in a direction that makes you concerned for the comfort and safety of other learners.

Below are some potential responses for handling difficult moments (Sexual Violence and Prevention Response Office, 2020):

8

Self-care and community care are about looking after yourself and those around you. Facilitating learning about sexual violence can range from satisfying and rewarding to challenging and overwhelming. It is important to make sure that you are able to take the time to take care of yourself and that you are willing to reach out to co-workers, friends and family, or professional supports, if needed.

Ideally, you will be in a situation where you are delivering training with a co-facilitator. Not only is this helpful if a learner needs support during a session, it also helps to have someone with whom to share the joys and challenges of facilitation. After a session, plan for time afterwards to check in with each other about your experiences and any successes or challenges in facilitating. This allows for time to reflect on issues related to participation, inclusion, and safety; to consider any feedback that you received from learners; and, to discuss any facilitation successes and challenges. If you are facilitating alone, you might use the time after a session to reflect or use a journal to make notes as a way of processing the experience.

Check-in/Reflection Questions

Taking time after a session to “debrief” can be a helpful way to care for yourself. Here are some sample debriefing questions.

III

9

A bystander is someone who is a witness to an event or situation. Active bystander intervention training aims to provide all member of a campus community with the skills to recognize and respond to sexual violence. Active bystander intervention training views sexual violence as a societal problem in which everyone can play a role in preventing. It aims to help change social norms (e.g., victim blaming) and encourage people to be both proactive and reactive to situations in which sexual violence may occur.

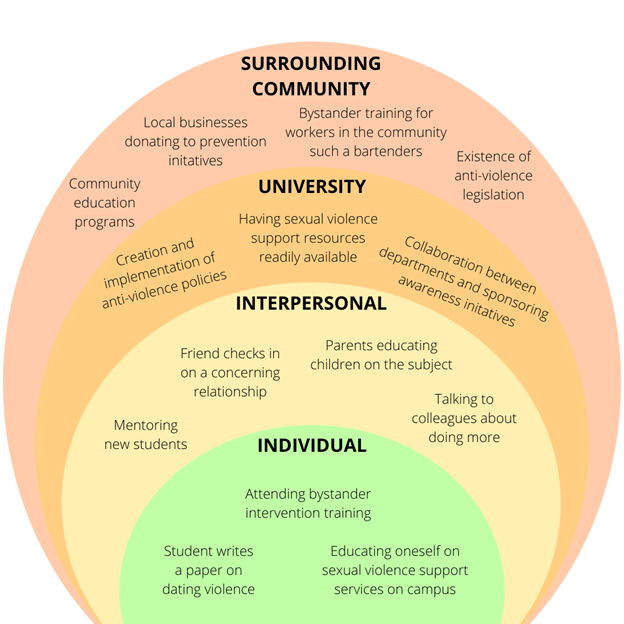

This training is grounded in a socio-ecological model (below) which allows learners to consider how actions and interaction at multiple levels can both perpetuate violence and be places for intervention. Research suggests that the connection to community belonging shows promise in facilitating bystander behaviour (Baynard et al., 2009; Bennett et al., 2014; Casey & Lindhorst, 2009; Levine et al., 2020; McMahon et al., 2019).

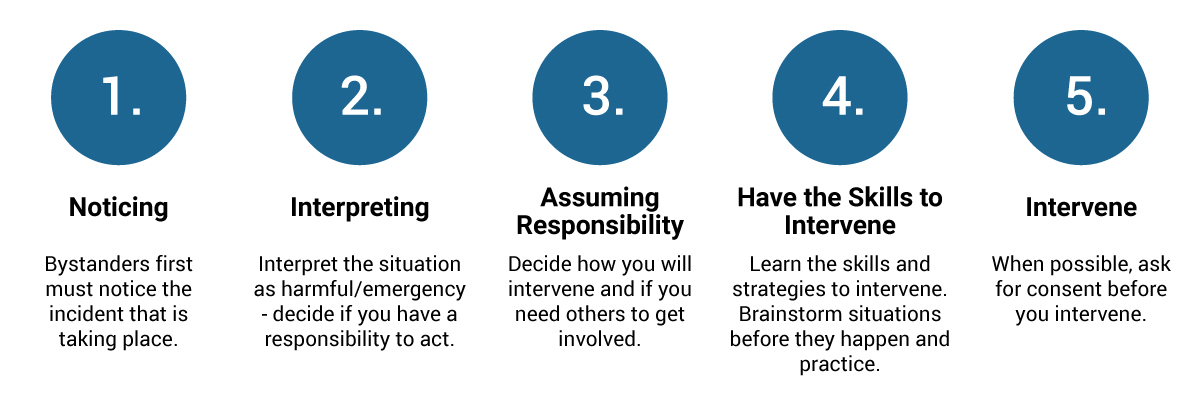

This training takes learners through the 5-step model of bystander intervention (Baynard et al., 2009; Bennett et al., 2014). Following promising practices outlined by Baynard et al. (2009, p. 450), this training intentionally wove the following components throughout:

Social-Ecological Model and Active Bystander Intervention image description.

A diagram with four semi-circles on top of each other to show the different levels where sexual violence can be prevented. They are as follows:

The 5-Step Model of Bystander Intervention image description.

End of chapter.

10

| Learning Outcomes | At the end of this workshop, learners will be able to:

|

|---|---|

| Audience | This training is suitable and recommended for all members of the campus community: students, faculty, administrators and staff. The suggested minimum number of learners is 6 and the suggested maximum is 40. |

| Duration | Approximately 90 minutes. |

| Knowledge and Skills | This workshop is designed to support learners in taking care of the campus community and responding to sexual violence when they see it happening. It teaches learners about what violence can look like, why it happens, and four strategies to respond if they see it happening. Learners will have space to hear and reflect on new information in addition to discussing and applying their learnings. |

11

This training can be delivered both in-person and remote (online) formats. Details on how to adapt the training for different formats can be found in the facilitator notes for the activities. In most instances, delivering this training in person is preferable. In-person delivery usually provides a greater opportunity for connection and relationship building between facilitator and learners, greater engagement between all learners, and more opportunities for facilitators to check for comprehension. Advantages for remote delivery include convenience, ability to reach students off- campus or prior to arriving on campus and the ability to record trainings. While this training is designed to be delivered synchronously, it can be adapted by individual institutions to be asynchronous.

An ideal institutional practice would see all students, faculty, administration (including leadership) and staff complete this workshop early in the school year, perhaps within a suite of trainings (i.e., other training on preventing and responding to sexual violence). Regular updates of sexual violence trainings (e.g., yearly) is also a “wise practice.”

Throughout the training, there are opportunities to adapt the training for different audiences by using different examples and scenarios. There are also brief activity slides throughout the presentation to assess learners’ knowledge and comfort level with the materials. This can help you decide which activities to spend more time on and when there might be opportunities to deepen the discussion and practice more advanced skills.

There are multiple opportunities to connect content found in this workshop to other training on sexual violence. For example, conversations about rape culture and myths about sexual violence in training on responding to disclosures can be linked to bystander intervention skills and how learners would respond to these situations. This training can also be included as part of the curriculum for various programs, a professional development opportunity for faculty and staff, or an extra-curricular credit offering.

12

The intended 90 minute length aligns with other post-secondary based bystander programming and it is appropriate to be delivered via peers when they have been adequately trained (Baynard et al., 2009; Mujal et al., 2019). While this workshop is informed by best available evidence, it is important to recognize that the published research does not necessarily include or represent all the diversity we find on our campuses (Evans et al., 2019; Hoxmeier et al., 2020; McMahon et al., 2020). As such, we invite and encourage you to thoughtfully tailor the message framing, scenarios, and structure to meet the needs of your audience.

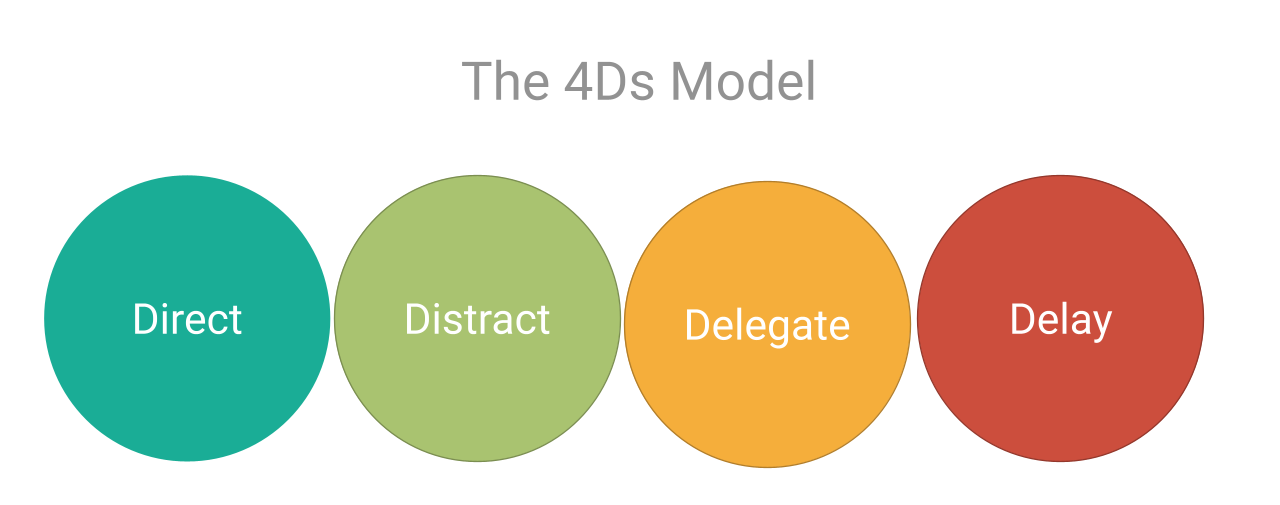

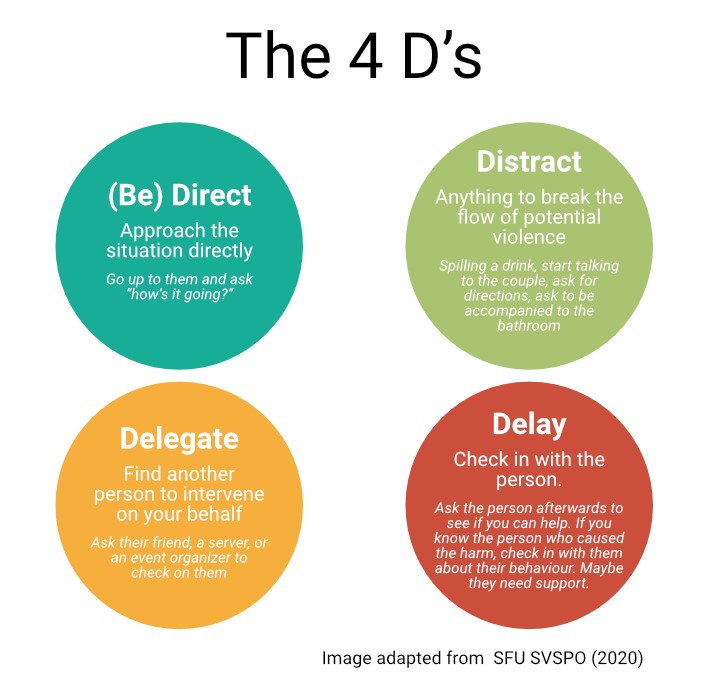

This training uses the 4Ds Model of Active Bystander Intervention. There are many versions and slight adaptations to this model available online, in purchasable programs and in the academic literature. If there is an aspect of the model that seems unclear or does not appear to fit into your context, you are encouraged to explore online resources that might work better. You may also want to explore various resources prior to delivering the training to deepen your own knowledge and understanding.

Examples of resources on the 4D Model:

The need to intervene during instances of online/digital violence is increasingly common. While violence and intervening online could be a separate training on its own, it may come up in this training as well. If you have additional time you may want to explore this area with learners. The resources below may be helpful tools for expanding this training to address these issues.

Below are some considerations for specific groups of learners.

Research has consistently indicated that men participating in bystander intervention training may benefit from additional support and/or alternative message framing (Katz 2018; Leone & Parrott, 2018; Reynolds-Tylus, et al., 2020). Because the topic of sexual violence can sometimes feel patronizing or identify only men as harm-doers, men can become reactant and disengage with the training. Suggestions to mitigate this include opening up and inviting discussion rather than relying solely on a lecture style, recognizing the diversity of perpetrators and victims, addressing larger social context and norms that allow people to choose violence, and encouraging the idea that everyone has a role to play in preventing violence. Facilitators with time and capacity could develop further tailored programming in this area to address the needs of learners. Engaging male allies in this work as presenters, co-facilitators and peer mentors would be valuable.

Resources

Facilitators looking to expand their knowledge and skills related to engaging men in bystander intervention training are encouraged to explore the following resources, which include facilitation manuals, publications, campaigns, and toolkits.

International students may be at significant increased risk of being targeted for sexual violence, due to multiple barriers they face including lower levels of English language fluency, a lack of understanding of criminal law in Canada, cultural views of violence, isolation, discrimination, racism, and a need to adjust to local culture and limited local support systems (Forbes-Mewett, McCulloch 2015). Research suggests that international students are reluctant to report sexual violence because of shame, guilt and embarrassment. Cultural norms may also hinder their ability to identify behaviors of others that may develop into situations of risk. Other factors include fear of not being believed, concerns about confidentiality and fear of retaliation by the offender. The majority of sexual assaults are committed by someone the victim knows and could include a friend, co-worker, person in authority, spouse or someone in their trusted peer group. International students face a number of transitional challenges related to adapting to the host culture leading them to turn to each other for support. Most often they form their own social network composed of other international students or former international students who share the same language and culture. Not only is there increased vulnerability for sexual violence from the larger community, international students may face sexual violence from other international students within their peer circle.

Bystander intervention will be better understood by inviting international students to safely discuss their fears, cultural expectations, unfamiliar norms, values and beliefs of the host student population and to identify concerns they may have about their safety and wellbeing. Information about the law, consent and resources should help to reduce anxiety and increase confidence to reach out for help and access culturally and linguistically pertinent resources. All students can play a role in being an active bystander and intervening to stop an incident.

People in the LGBTQ2IA+ community are disproportionately targeted by perpetrators of sexual violence. Because of the lasting societal prevalence of homophobia, transphobia and queerphobia, they may be isolated from supportive networks of families and friends. Experiences with medical professionals and the criminal justice system may not offer culturally competent support or a sense of safety for queer victims of sexual violence. Likewise, victims of queer sexual violence may be reluctant to seek support or report the harm done to them (e.g., a straight, cisgender man may feel shame about being targeted by another man and choose not to seek support). Care must be taken to understand and acknowledge the intersecting oppressions faced by LGBTQ2IA+ folks of colour and those who are disabled and Indigenous. If at all possible, offer community and campus resources for queer victims of sexual violence that are culturally relevant (i.e. resources for Two Spirit people, queers of colour, disabled queers, religious queers, etc.).

13

This section complements the facilitator notes included in the slide deck. It provides suggestions on alternative ways of facilitating activities and how to “go deeper” into topics depending on time available, audience interest, and goals for the training.

Land Acknowledgement: Adapt your institution’s land acknowledgement. Territorial acknowledgements are designed as the very first step to reconciliation. See Section 1 for additional information about creating a land acknowledgement for this training.

Optional Introductory Ice Breaker: You may choose to include an ice breaker activity at the beginning of your training to provide learners with an opportunity to get to know each other. Below is an example of an activity that can be used for both in-person and online trainings.

Give learners a moment to examine this photo (or another similar photo) and then ask them:

Explore the different things people pick up on in the image, different perspectives on what’s happening, and how they might respond in the moment. Connect back to being a bystander in situations involving sexual violence. This activity is useful for “lightening the mood” or if there’s a lot of discomfort around the topic.

Help create a safe and respectful space through the use of a community agreement. See Section 2: Creating Space for more information about the use of community agreements.

Slide 4 describes an activity that you can use to help learners identify strategies for taking care of themselves during and after the training. You can use the Wellness Wheel to discuss different types of wellness and different approaches to self-care. You can also expand this part of the training by providing learners with the opportunity to more deeply explore wellness and self-care by using the Wellness Wheel handout below.

The Wellness Wheel was developed by Jewell Gillies, Musgamgw Dzawada’enux (they/them/theirs), and aligns with Indigenous traditional practices that view wellness holistically. You can download a handout version to share with learners here: BCcampus Wellness Wheel Worksheet [PDF].

During this discussion, you should make sure that learners know what supports are available on campus and in community, and that you will be available after the workshop to debrief with anyone who might need additional support. Additionally, let learners know that they can private message a specific facilitator (email).

You can also deepen this discussion of self-care by talking about individual self-care versus community care and institutional support and resources. Self-care can often have an overly individual focus on it as people are encouraged to take care of themselves. Similar to how we encourage learners to think beyond the individual to systems and structures when we talk about preventing sexual violence, we need to expand our understanding of self-care and wellness. (This concept is relevant for learners, but it is also important for facilitators to consider for themselves. This is not easy or uncharged work to do, and it is both important and encouraged to acknowledge what kind of needs you may have to stay well in the work). Resources that may be helpful to review to support this type of discussion include:

This short video with Jewell Gillies is an opportunity to ground discussions about bystander interventions in the context of community relationships and Indigenous ways of knowing. Following the video, you can highlight the following points:

Learning Objective(s) Addressed: Define sexual violence

Intent: to ensure learners understand terms used by their institutions they attend/work at.

Explain the importance of knowing what the terms mean, especially as language is ever changing and the meanings can vary depending on things like culture or setting (i.e., slightly different between different universities or from province to province). Because of the fluidity of language, it is important to define terms folks say they understand as well as the terms that they are unsure about. You are encouraged to make this piece interactive. Depending on time, you could choose one of the following options for a few terms, then distribute a full definitions page and let learners know it is their responsibility to be aware of what the terms mean at your institution.

Learning Objective(s) Addressed: Recognize the complex roots of sexual violence and how social influences normalize violence.

Intent: to gauge and gather learners’ ideas about sexual violence, to promote deeper reflection about why violence happens, to challenge myths that come up.

Recognize that learners are coming from diverse backgrounds and histories with different experiences and may have lots of ideas and knowledge about this already.

Option 1: Allow learners 30 seconds or so to silently reflect on “What causes sexual violence” and write down an idea or two.

Collect responses in one of these ways:

Option 2: create a poll in Kahoot or Slido with preloaded answers such as:

Sexual violence happens because:

Debrief answers received and use as transition to Continuum of Violence slide.

Learning Objective(s) Addressed: Recognize the complex roots of sexual violence and how social influences normalize violence.

Intent: to practice recognizing how everyday interactions and social messaging can perpetuate rape culture.

Learning Objective(s) Addressed: Develop skills to intervene and be an active bystander if you see sexual violence happening

Intent: to reflect on personal experience of situations where bystander intervention is possible; to start identifying positive and negative impacts or attributes bystanders can have; to emphasize the importance of thinking about safety and the victim/survivor’s perspective before jumping into action.

Learning Objective(s) Addressed: Develop skills to intervene and be an active bystander if you see sexual violence happening.

Intent: To acknowledge that there are good reasons (i.e., risk of other forms of discrimination) why people do not intervene sometimes; to highlight that an intervention does not have to be “perfect” to be useful or helpful.

Learning Outcome(s) Addressed: Developing skills to intervene and be an active bystander if you see sexual violence happening.

Intent: to practice specific intervention skills and strategies using real life circumstances.

5 minute group work, 10 minute debrief.

You are waiting for the bus on campus after a long day with a group of people you are friendly with. You notice a student who is waiting for the same bus being approached by someone they seem to know and are being flirtatious with. Something in their conversation and body language changes as the bus pulls up. The student looks upset and rushes onto the bus, you hear them say firmly, “I said I am not interested!” The person they were flirting with looks confused and follows them onto the bus.

Kai has just been hired in your department as the new administrative assistant. Your co-worker Shay is responsible for training all new staff. Shay is friendly and generally very funny. A few weeks after Kai starts, you notice Shay hanging out at Kai’s desk. As you get closer, you can hear Shay talking about how nice Kai’s eyes are. Shay laughs, “Oops, you better not tell HR about that!” Kai doesn’t laugh or say anything in response.

Later that day you hear Shay asking for help with a jammed photocopier. As Kai bends over to help, you see Shay glancing at Kai’s bum. With a laugh Shay says, “I guess your eyes aren’t the only nice thing about you.”

After an exam, you and some classmates go out to celebrate. After a few drinks, one of them starts talking about a date he went on the weekend before. Ash talks loudly about how he could tell immediately that his date was going to have sex with him that night. Some classmates remain silent, pretending to be distracted by their phones or the menu. A few classmates chime in about their own sexual encounters on first dates, joking about how to tell by someone’s dating profile picture how likely they are to be open to having sex or hooking up. Ash asks a quiet classmate, “Would you have sex on the first date?” When the quiet classmate responds, “Not with you!” Ash suggests that he would just have to get the classmate drunk first to loosen them up.

Though you may not have heard what was said between the two flirtatious people in this scenario, you may guess that something is not quite right from context clues like changes in body language and tone. You may not be completely sure that you have witnessed sexual violence or harassment, but it’s better to be an active bystander than to be a passive one — just in case.

Sometimes being in a group of people we feel safe with changes the way we intervene when we witness sexual violence or harassment. We might be more or less likely to get involved based on our relationship within the group. For example, the bystander effect can kick in here if no one else in your group responds to help the student. You might second-guess your instincts to intervene because you aren’t sure that what you are witnessing is, indeed, some form of violence or harassment. You might wait for someone else in your friend group to make the first move if you assume they are better suited to intervening (maybe they are bigger, stronger, or feistier than you). On the other hand, you may feel safer to use one of the 4 D’s if you are surrounded by safe people who you think may support you in your efforts to intervene. There can be strength in numbers in this scenario. For example, you and your friend group could, if you wanted to, form a protective shield between the student and the person they were flirting with once you all get on the bus. Which of the 4 D’s would that be?