Special Clothing (Uniforms)

Many employees in the restaurant and food service industry are required to wear uniforms when they are at work. If you must wear a uniform or a specific brand of clothing, the employer must provide, clean, and maintain it. For example, many cooks must wear white jackets and hats and checked trousers. Your employer must buy the uniform. You cannot be charged for the uniform or for damages to it. Your employer cannot require you to pay a deposit for the uniform or withhold your wages.

The majority of employees and the employer may agree that employees will clean and maintain the special clothing and be reimbursed by the employer for the expenses incurred. This agreement is binding on all employees in the workplace who are required to wear the special clothing.

If an employer and a majority of the employees have agreed that the employer will reimburse employees for the cost of cleaning and maintaining special clothing, the employer must keep records of the agreement and the amounts paid for two years.

Statutory Holidays

Restaurant and food service workers are often required to work when others are on holiday. Holidays such as Christmas and New Year’s Day are frequently the times that people want to go out for dinner, and so restaurants may be especially busy during these times. These days are known as statutory holidays. In British Columbia, the following days are statutory holidays:

- New Year’s Day (January 1)

- Family Day (third Monday in February)

- Good Friday (changes from year to year)

- Victoria Day (the third Monday in May)

- Canada Day (July 1)

- B.C. Day (the first Monday in August)

- Labour Day (the first Monday in September)

- Thanksgiving Day (the second Monday in October)

- Remembrance Day (November 11)

- Christmas Day (December 25)

Easter Sunday, Easter Monday, and Boxing Day are not statutory holidays, although some employers may provide paid time off on these days.

Eligibility

You are not automatically eligible to statutory holidays with pay as soon as you have begun work. You must have worked for the employer for at least 30 calendar days.

Managers (that is, those whose primary employment duties consist of supervising and directing other employees) or a person employed in an executive capacity are not entitled to statutory holidays. They may, however, have negotiated similar provisions in their terms of employment.

Calculating Statutory Holiday Pay

If you have a regular schedule of hours and if you have worked at least 15 days out of the last 30 calendar days prior to a statutory holiday, you are entitled to a regular day’s pay for the holiday. If you have worked irregular hours on at least 15 out of the last 30 calendar days, you are entitled to an average day’s pay for the holiday. This amount is calculated by dividing the employee’s total wages, excluding overtime, by the number of days worked.

An employee who has worked fewer than 15 days in the 30 calendar days before the holiday is entitled to pro-rated holiday pay. This amount is calculated by dividing the total pay during the period, excluding overtime, by 15.

For example, Meilin, Ming, and Steve are all employed in a local restaurant. Meilin is a regular employee who worked 20 eight-hour shifts over the 30 days prior to the holiday. She is entitled to eight hours of pay on the statutory holiday. Ming started work just two weeks before the holiday. He is not entitled to be paid for the holiday. Steve is a part-time employee who has been working for the restaurant for six months. He worked only 12 shifts during the 30 calendar days before the holiday and earned $480 during that time. He is entitled to a payment of $480 ÷ 15 = $32.00 for the holiday.

But what would happen to an employee who is on paid vacation leave prior to the holiday? According to the Act, the vacation days and vacation pay are counted as days worked and wages earned when calculating statutory holiday pay.

Working on a Statutory Holiday

Cooks and other workers in the restaurant and food service industry often work on statutory holidays. It is no surprise that the legislation covers this situation. If you work on the holiday, you must be paid time-and-a-half for the first 12 hours you work and double time for hours beyond 12. You must also be given an alternate day off with pay. If you have a time bank, you may credit the wages for the alternate day.

The employer must schedule the alternate day of paid leave on the earliest of the following:

- Before the employee’s annual vacation

- Before the date the employment terminates

- Within six months of the statutory holiday if the wages were credited to a time bank

Employees not eligible for the statutory holiday who work on the holiday may be paid as if it were a regular workday. They are not entitled to the day off. If a statutory holiday falls on a day on which you are not normally scheduled for work, you are entitled to an alternate day off with pay. This day must be scheduled as if you had worked on the statutory holiday.

By agreement between the employer and a majority of affected workers, the employer may substitute another day off for a statutory holiday. For example, the employer and staff may agree to substitute Easter Monday for Good Friday. The Act and the Regulations will then apply to Easter Monday as if it were a statutory holiday. If the employer and a majority of employees have agreed to substitute another day for a statutory holiday, the employer must keep records of this agreement for two years.

Leave from work

Employers must grant employees periods of unpaid absence from work for the following:

- Pregnancy leave

- Parental leave

- Family responsibility leave

- Bereavement leave

- Jury duty

Employees are eligible for unpaid leave as soon as they have commenced employment. Employers are not required to give employees paid leave for illness. If sick leave is paid or allowed, it may not be deducted at a later date from any other entitlement to a paid holiday, vacation pay, or other wages. Employees who are ill for extended periods of time may be eligible for Employment Insurance.

Pregnancy leave

A pregnant employee is entitled to up to 17 consecutive weeks of unpaid pregnancy leave. This leave may start no earlier than 11 weeks before the expected birth date and end no earlier than six weeks after the birth period unless the employee requests a shorter period. If the pregnancy leave is first requested after the birth of a child or after termination of the pregnancy, an employee is entitled to up to six consecutive weeks of leave beginning on the date of birth or termination date.

An initial period of leave may be extended up to six weeks if an employee is unable to return to work for reasons relating to the birth or the termination of the pregnancy.

The employee must apply, in writing, to take a pregnancy leave. The request must be made at least four weeks before the proposed start date. If the employee wishes to return to work earlier than six weeks from the birth date, she must make the request to return at least one week before the proposed start date. The employer may require the employee to provide a doctor’s certificate in support of a request for leave or for a leave extension. Pregnancy and parental leaves are unpaid leaves, but you may be eligible for maternity and parental benefits under the Canada Employment Insurance Program.

Parental leave

Parental leave is available to a birth mother, a birth father, or an adopting parent.

A birth mother is entitled to up to 35 consecutive weeks of unpaid parental leave in addition to the pregnancy leave she has taken. If she has not taken pregnancy leave, the birth mother is eligible for up to 37 consecutive weeks of unpaid parental leave. A birth mother will commence her parental leave immediately after her pregnancy leave ends unless the employee and employer agree otherwise. A birth mother who is entitled to up to 37 weeks of leave will commence the leave after the child’s birth and within 52 weeks of that event. A birth father is entitled to up to 37 consecutive weeks of unpaid leave beginning after the child’s birth and within 52 weeks of the event. An adopting parent is entitled to up to 37 consecutive weeks of unpaid parental leave beginning within 52 weeks after the child is placed with the parent.

Parents must apply in writing for parental leave at least four weeks prior to the proposed start date of the leave. An employer may require an employee to provide a doctor’s certificate or other evidence that the employee is entitled to the leave or leave extension.

As soon as parental leave ends, the employer must place the employee into the position previously held by the employee or in a comparable position.

Family responsibility leave

An employee is entitled to up to five days of unpaid leave per employment year to meet responsibilities related to the care, health, or education of any member of the employee’s immediate family. Under the legislation, immediate family means the spouse, child, parent, guardian, sibling, grandchild, or grandparent of an employee, and any person who lives with the employee as a member of the employee’s family.

For example, Bart lives in a household with his mother-in-law and children. Bart’s mother-in-law has broken her hip and requires surgery. Bart is entitled to family responsibility leave in order to care for her. Susan and Pat live together. In the event of an illness, Pat would be entitled to leave to care for her partner.

Bereavement leave

Employees are entitled to up to three days of unpaid leave on the death of a member of the employee’s immediate family.

Jury duty

Jury duty is considered a responsibility of citizenship for all citizens of Canada. Individuals may be excused from jury duty only if a judge feels that the duty would impose undue hardship on the individual and his or her family. An employee who is required to attend court as a juror is considered to be on unpaid leave for the period of the jury duty.

Employment considered continuous

During the time an employee is on unpaid leave, employment is considered continuous for the purposes of calculating annual vacation and termination entitlements, as well as for pension, medical, or other plans of benefit for the employee. An employer must continue to make payments to any such plans unless the employee chooses not to continue with his or her share of the cost of the plan. The employee is also entitled to all increases in wages or benefits which he or she would have received if not on leave.

Conditions of employment

An employer cannot terminate an employee on leave or jury duty or change a condition of employment without the employee’s written consent. As soon as the leave or jury duty ends, the worker must be returned to his or her former position or a comparable one.

Consideration for the employer

Whenever possible, it is only considerate to inform the employer as soon as possible when leave is required. For example, if you have been called for jury duty, you will have been given a date on which to appear at the courthouse. Let your employer know so that alternate arrangements can be made for your replacement. Of course, there are times, such as the sudden illness or death of a family member, when it is not possible to notify your supervisor ahead of time. However, you should do your best to call as soon as you can and give the supervisor an idea of when you will return.

Annual vacation

After you have been employed for 12 consecutive months, you are entitled to two weeks of paid vacation. After five consecutive years of employment with the same employer, you are entitled to three weeks. During the first 12 months of employment, the Employment Standards Act does not require that you be granted an annual vacation. However, the terms of employment or a collective agreement may provide additional vacation benefits.

An employer must schedule an employee’s vacation in periods of one or more weeks, unless the employee requests otherwise. Vacation must be taken within 12 months of earning it. The employer may use a common date for calculating the annual vacation entitlement of all employees as long as no employee’s right to an annual vacation or vacation pay is reduced.

If the company is sold, leased, or transferred during the year, your period of consecutive employment is not interrupted. For example, the restaurant in which Sally works was purchased by another chain and subsequently closed, but she was transferred to another location operated by the purchasing company without any loss of employment. Her period of employment was not interrupted, even though her pay cheques were now issued by another company.

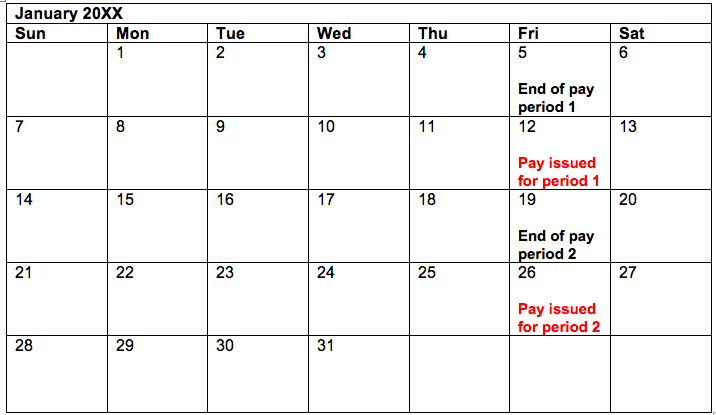

Vacation Pay

In the first four years of consecutive employment, the employer must pay vacation pay of at least 4% of all earning paid to the employee in the preceding year. In the fifth and subsequent years of employment, the employer must pay vacation pay of at least 6% of all wages paid in the preceding year. Any vacation pay received by an employee is counted as part of the total wages paid in a particular year. Employees who have worked five calendar days or less are not eligible for vacation pay.

If a statutory holiday falls during the period in which the employee is on annual vacation leave, the employee must be given an additional day of vacation leave in lieu of the statutory holiday. For example, Raj is on holiday for two weeks at the beginning of September. This period includes one statutory holiday, Labour Day. He must be given an additional day of holiday at another time or may have a day in lieu of the statutory holiday added to the beginning or end of his vacation period.

Vacation pay is payable at least seven days before the start of the annual vacation, or on regular pay days as agreed to by the employer and employee, or by a collective agreement.

An employer cannot reduce annual vacation or vacation pay because the worker was paid a bonus or sick pay, or was previously given a vacation more than the minimum. However, these vacation entitlements may be reduced if an employee took annual vacation in advance at the employee’s written request.

If your employment is terminated before you have taken your annual vacation or if you quit your job, you are entitled to be paid any vacation pay that has accrued since you started work or last took annual vacation. This payment must be made within 48 hours if your employment was terminated or within six days if you quit your job.

Hours of Work

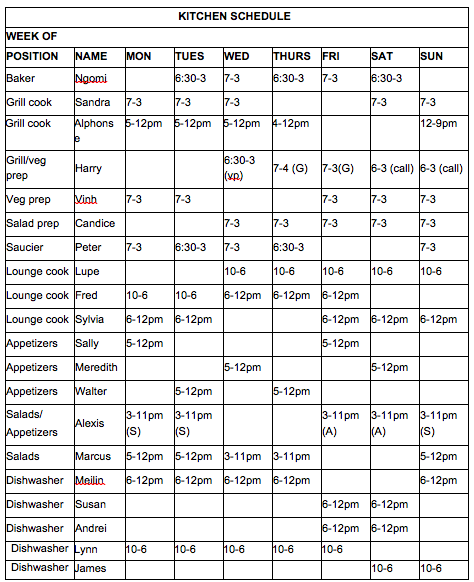

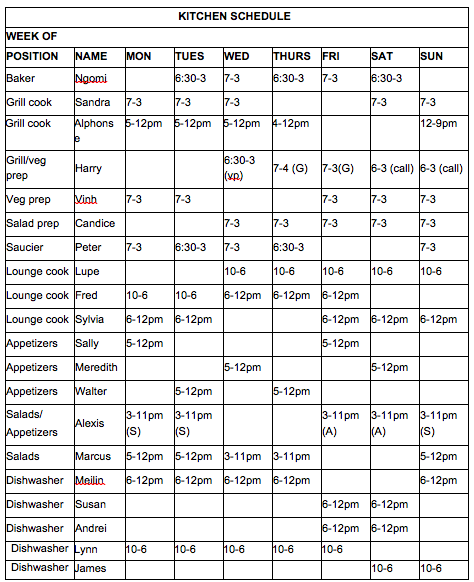

The employer must post notices saying when work starts and ends, when each shift starts and ends, and when meal breaks will occur (Figure 6). For example, a restaurant may have a morning shift that begins at 6:00 a.m. and ends at 2:00 pm. The workers on that shift get a meal break at 9:30 am. These notices must be posted where they can be read by all employees.

Figure 6. Sample shift schedule

Shift changes

In the food service industry, work schedules are often developed with different start and end times for different employees. In addition, the industry is sometimes subject to changes in the demand for service. A restaurant may be unexpectedly busy on a day that is normally quiet. Employees must be given 24 hours’ notice of a change in shift unless the employee is paid overtime for the time worked or the shift is extended before it ends. If the employee has not been given the required notice, he or she cannot be penalized for failing to show up for work.

This means, for example, that if a restaurant is extremely busy, you may ask Genevieve, the bus person, to stay for an additional two hours an hour before she finishes her five-hour shift without paying overtime. This assumes that she is not entitled to overtime because of the number of hours she has worked in this pay period or because of a collective agreement.

Meal breaks

After working for five hours in a row, employees are entitled to a half-hour meal break. An employee who is required to work or be available for work during a meal break must be paid for the break. In the food service industry, breaks are often taken between a rush of customers, and a cook may have to cut a break short to cope with new orders. If the cook must be prepared to cut a break short, she or he must be paid for the break, even if on that day the break was not interrupted.

Coffee breaks are not required by the legislation. Employers have the discretion to give coffee breaks. Some collective agreements may specify coffee breaks as part of the conditions of employment.

Split shifts

A split shift is a work pattern in which an employee works for several hours, is off for several hours, and then is asked to work for another period during the same day. When an employee is scheduled for a split shift, the employee must finish for the day within 12 hours of the time he or she began the shift. For example, you could not schedule a dishwasher to come in from 7:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m., and then again from 6:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. on the same day. You could, however, have the dishwasher work from 11:00 to 3:00 and then again from 6:00 to 10:00 for the same number of total hours.

Excessive hours

Employers must not require or allow an employee to work excessive hours or hours harmful to the employee’s health or safety. At present, what constitutes excessive hours is not specified in the Act or Regulations.

Minimum daily pay

An employee who starts work must be paid for at least two hours, even if the employee works for a fewer number of hours. If the work is suspended for reasons beyond the employer’s control, for example, a power failure due to a storm that cannot be repaired that evening, the employee must be paid for two hours of work or the actual number of hours worked, whichever is greater.

For example, a restaurant is experiencing a very slow night. Normally, this evening would be busy, but perhaps because of the cooler temperatures, people are staying home. You could be sent home early, but your employer would have to pay you for at least two hours.

If an employee has reported for work but has not actually started work, he or she must be paid for at least two hours if there is insufficient work. The exception is if the employee is unfit for work or does not comply with the health and safety provisions of WorkSafeBC regulations. For example, an employee who shows up for work under the influence of alcohol could be sent home without being paid for a minimum of two hours.

Hours Free from Work

Employees must have at least 32 hours in a row free from work each week. If an employee works during this period, the employer must pay one-and-a-half times the regular wage for the hours worked. An employee is also entitled to have eight hours off between shifts unless the employee is required to work because of an emergency.

For example, a cook has been working from 5:00 p.m. to midnight on a Thursday evening. The cook is due for a break of at least 32 hours. The earliest he or she could be scheduled after the break would be at 8:00 a.m. on Saturday morning.

Overtime

The standard work day is eight hours and the standard work week is 40 hours. If employees work over eight hours in a day or over 40 hours in a week, they must be paid overtime. The exception is when the employer has implemented a flexible work schedule or if the Employment Standards Branch has granted a variance. Depending on the schedule worked, an employee could be eligible for overtime on the basis of the hours worked in a day, the hours worked in the week, or both. Daily and weekly overtime are calculated separately.

An employer can require you to work overtime as long as the applicable overtime wage rates are paid. In addition, the hours worked should not be excessive or detrimental to the employee’s health or safety. Excessive is not defined in the Act or Regulations. In the case of a dispute, the Director of the Employment Standards Branch would be required to adjudicate what excessive hours are.

Daily and weekly overtime

After working eight hours in a day, an employee is entitled to time and a half for the next four hours worked, and double time for all hours worked in excess of 12 hours.

After working 40 hours in a week, employees must be paid time and a half for the next eight hours and double time for hours in excess of 48. In calculating the total hours worked for weekly overtime purposes, only the first eight hours worked on each day are counted.

For example, if Mohinder works 10 hours on Sunday, seven hours on Monday, seven hours on Tuesday, eight hours on Thursday, and eight hours on Friday, he has worked a total of 40 hours over the five days. He was also asked to work on Saturday. His employer gave the required 24 hours’ notice. For the purposes of calculating weekly overtime, only the first eight hours of each day would be counted. The first eight hours on Sunday would be counted as would all of his shifts on the Tuesday through Friday for a total of 38 hours. He would be paid regular time for the first two hours he worked on Saturday, and after that would receive time and a half. Of course, he would also receive one and a half time (daily overtime) for the extra hours he worked on the Sunday.

In a week with a statutory holiday, an employee who qualifies for the holiday must be paid weekly overtime and time and a half after 32 hours and double time after 40 hours. Any time worked by the employee on the holiday is not included in calculating weekly overtime.

Banking overtime

Employees may request in writing that the employer establish a time bank and credit the employee’s overtime wages to the bank instead of paying the wages as they are earned. An employee may at any time request the employer to pay out all or part of the wages in the time bank. The employee may also request time off with pay for some mutually agreed period.

An employee may request that the time bank be closed. If the employee quits, is laid off, is fired, or has requested that the time bank be closed, the employer must pay the full outstanding balance to the worker. All banked wages must be paid out within six months of being earned. If a number of employees have time banks, then the employer can set a common date for paying out the banked time as long as all wages are paid within six months of being earned.

Training

If the employer requires the employee to attend a training or orientation session or attend a meeting outside of the employee’s normal working hours, the employee must be paid. The employee may be eligible for overtime, minimum daily pay, or other provisions under the Act. For example, George was required by his employer to attend a one-hour training session on a day he was not scheduled for work. He must be paid for at least two hours (minimum daily pay). If he had already worked 40 hours in that week, then he must also be paid overtime.

Flexible Work Schedules

Flexible work schedules are schedules in which the employees may work more than eight hours on a given day or 40 hours in a given week without being paid overtime. For example, an employer may agree to a four-day work week in which employees work 10 hours each day.

This may be beneficial to both employers and employees. Employers may find that scheduling for their opening hours is easier and requires less overtime when a flexible work schedule is used. Employees may enjoy the extra day on which they do not work. Another example is the employer whose employees work nine 8.75 hours days in a two-week period. In one week, employees may work five days for a total of 43.75 hours, but the following week they work only four days (35 hours). The average number of hours per week over two weeks is just over 39 hours.

Workers not covered by a collective agreement

If the workers are not unionized, flexible work schedules must:

- Fit the models permitted by the Regulation

- Run at least 26 weeks

- Be approved by at least 65% of the affected employees

- Be submitted to the Employment Standards Branch within seven days of approval by the employees

Workers must be given an opportunity to hear about the proposed schedule and think about its implications. An information bulletin outlining the proposed schedule must be posted for at least 10 days prior to the approval by employees. Employers may cancel a flexible work schedule at any time. The Branch can also cancel a schedule if it is satisfied that the employer did not follow the procedures in the Regulation or that the employer forced any employees to approve the schedule. The Branch will act only after receiving a written complaint from one of the employees affected by the schedule. A schedule expires two years after it is approved, but may be renewed with the approval of 65% of the affected employees.

Where workers on a flexible work schedule work more than an average of eight hours a day or 40 hours a week over the shift cycle, overtime wages must be paid. For example, James normally works four 10-hour shifts per week. If on one of those days he is asked to work an additional three hours, he would be entitled to overtime for those hours. If he is brought in on a day he does not normally work, he would also be entitled to overtime wages.

Unionized employees

Where workers are covered by a collective agreement, the flexible work schedule must:

- Run for at least 26 weeks

- Consist of a shift cycle of days at work and days off work that repeats over a period of up to eight consecutive weeks

- Allow each affected employee to work an average of at least 35 hours and not more than 40 hours during the shift cycle at the regular rate of pay

- Be approved by the trade union representing the workers affected.

Overtime wages, as required by the collective agreement, must be paid when the employee works more than an average of eight hours per day or 40 hours a week over the shift cycle.

If your employer has a flexible work schedule, records relating to its approval must be kept for seven years.

Averaging Agreements

As opposed to a flexible or alternative work schedule, which is permanent, an employer may decide to use an averaging agreement for a short period of time when the employee’s schedule might vary. This could be used in the case of a business trip or an event that might require a few longer days one week and allowing extra time off the following week. As long as the total number of hours per week do not average more than 40, no overtime pay is required unless the employee works more than 12 hours in any one day, in which case regular daily overtime rates (double the usual hourly rate) will apply.

Averaging agreements can be for a term of one to four weeks and must be agreed to and signed by both the employee and employer in advance. They also must be accompanied by a schedule of anticipated hours over the entire period of the agreement and state the start and end dates of the agreement.

Layoff

Notice is also not required if an employee is laid off temporarily. A temporary layoff becomes a termination when a layoff exceeds 13 weeks in any period of 20 weeks, or a recall period covered by a collective agreement has been exceeded by more than 24 hours. A week of layoff is one in which the employee earns less than 50% of the regular weekly wages averaged over the previous eight weeks. If a temporary layoff becomes a termination, then the date of layoff becomes the termination date. The employee is entitled to the compensation for termination. Any layoff other than a temporary layoff is considered a termination.

Notice of termination

An employee who is terminated by an employer is eligible for compensation based on the length of her or his employment with the employer. The amount of compensation is as follows:

- After three months’ consecutive employment, one week’s pay

- After one year, two weeks’ pay

- After three years, three weeks’ pay, plus one week for each additional year of employment up to a maximum of eight years

If an employer substantially alters a condition of employment, the Employment Standards Branch may determine that the employee’s employment has been terminated. If the Branch decides that the employment was terminated, the employee is eligible for compensation.

A week’s pay is calculated by totalling the employee’s wages excluding overtime, earned in the last eight weeks of which the employee worked normal hours, and dividing by eight. As with calculations of annual vacation, the sale, transfer, or lease of the business does not interrupt an employee’s period of continuous employment.

Termination pay is required even if the employee has obtained other employment.

Compensation is not required if the employee is given advance written notice of the termination equal in number of weeks to the number of week’s pay for which the employee is eligible. An employee cannot be on vacation, leave, strike, or lockout, or be unavailable for work for medical reasons during the notice period. If employment continues after the notice period has ended, the notice is of no effect. Once notice has been given, the employer may not alter any condition of employment, including the wage rate, without the employee’s written consent.

An employer may give an employee a combination of notice and compensation equal to the number of weeks’ pay for which the employee is eligible.

For example, a hotel has just been sold to a developer who will turn the building into condominium units. The hotel owner employs 37 people including a number of cooks. The cooks have worked for the hotel for varying periods of time, ranging from five months to seven years. The owner has the option of giving the cooks notice of termination seven weeks before the closure of the hotel. One of the cooks was on three weeks’ holiday when the deal was signed. This employee, who had five years of continuous employment, could not be given notice. When the employee returned to work, four weeks before the closure, he was given four weeks’ notice and 1 week’s pay to compensate for the termination of employment. Alternatively, the employer could have provided compensation in lieu of notice for all of the employees.

Some examples of the appropriate compensation are as follows:

- Steve, five months of consecutive employment received one week’s pay

- Geoff, 13 months of consecutive employment received two weeks’ pay

- Anya, three years of consecutive employment received three weeks’ pay

- Lupe, seven years of consecutive employment received seven weeks’ pay

Notice of termination or pay compensation is not required if:

- The employee quits or retires

- The employee was dismissed for just cause

- The employee works on an on-call basis doing temporary assignments that may be accepted or rejected

- The employee was employed for a definite term provided that the employment was not extended for at least three months after the term was ended

- The employee was hired for specific work to be completed in 12 months or less

- Events or circumstances beyond the employer’s control (except bankruptcy, receivership, or insolvency) made it impossible to perform the work

- The employee refused reasonable alternative employment

Some employers in specific industries (e.g., construction) or those hiring persons in some occupations (e.g., teacher) may not be required to give notice or pay compensation on termination of employment.

An employer operating a seasonal resort would not have to give notice or pay compensation at the close of the regular season. The employees would be hired for a specific term ending on the closure date of the resort. If a fire destroyed the resort mid-way through the season, the employer would not be required to give notice or pay compensation because the fire is an event beyond the employer’s control. If, on the other hand, the resort was bankrupted during the regular season, while employees were still at work, notice or compensation would be required.

Temporary layoff

Notice is also not required if an employee is laid off temporarily. A temporary layoff becomes a termination when a layoff exceeds 13 weeks in any period of 20 weeks, or a recall period covered by a collective agreement has been exceeded by more than 24 hours. A week of layoff is one in which the employee earns less than 50% of the regular weekly wages averaged over the previous eight weeks. If a temporary layoff becomes a termination, then the date of layoff becomes the termination date. The employee is entitled to the compensation for termination. Any layoff other than a temporary layoff is considered a termination.

Group terminations

When an employer intends to terminate 50 or more employees at a single location within a period of two months, the employer must provide written notice of group termination to each employee affected. The employer must also notify the Employment Standards Branch and any trade union that represents the employees. The length of notice depends on the number of employees to be laid off:

- 50 to 100 employees, at least eight weeks before the effective date of the first termination

- 101 to 300 employees, at least 12 weeks before the effective date of the first termination

- 301 or more, at least 16 weeks before the effective date of the first termination

Employers must give termination pay or a combination of termination pay and notice if the employees are not given the notice by the group termination requirements. If an employee is not covered by a collective agreement, the notice and termination pay requirements are in addition to the requirements based on length of employment.

If the employer is in receivership, bankruptcy, or insolvency, the provisions for group termination do not apply. However, the employee is still entitled to the amount which is payable as a result of length of employment, or the amount payable for an individual termination under the collective agreement, whichever is greater.

Employees covered by collective agreements

If an employee covered by a collective agreement that includes individual termination and right of recall provisions is laid off, the employee must choose to be paid the amount of compensation required by the collective agreement or to maintain his or her right of recall under the collective agreement. If the employee chooses to be paid, then the employer must pay that amount within 48 hours. If the employee chooses to maintain the right of recall or does not make a choice after 13 weeks of layoff, the employer must pay the amount required by the collective agreement to the Employment Standards Branch, in trust. Amounts received in trust receive interest and are paid to the employer if the employee is recalled.

If the employee renounces the right of recall or is not recalled to employment during the period required in the collective agreement, the amount held in trust is paid to the employee. Employees who accept employment under the right of recall do not have the right to payment of the money held in trust.

Other laws

Even in cases where no compensation or notice is required under the Employment Standards Act, other laws such as the Human Rights Code and common law regarding termination and wrongful dismissal may apply to a particular termination. Employers are required by federal government legislation to provide employees with a Record of Employment when they quit or are terminated. They must also issue a T-4 to employees who have income tax, Canada Pension, and Employment Insurance premiums deducted from their pay cheques whether or not they were working for the employer at the end of the year. The T-4 must be issued by February 28 of the following year.