Meat grading for beef is governed by the Canada Agricultural Products Act and the Livestock and Poultry Carcass Grading Regulations, which also apply to all other domestic species where grading is used. Grading standards and criteria differ somewhat for each species.

Grading is carried out on the animal carcass, which must already be approved for health and safety standards and bear an inspection stamp. Grading categorizes carcasses by quality, yield, and value, and provides producers, wholesalers, retail meat operations, and restaurants the information they need to purchase a grade of meat that suits their particular needs. Grading is also intended to ensure that the consumer has a choice in selecting a consistent and predictable quality of meat.

Beef Grading

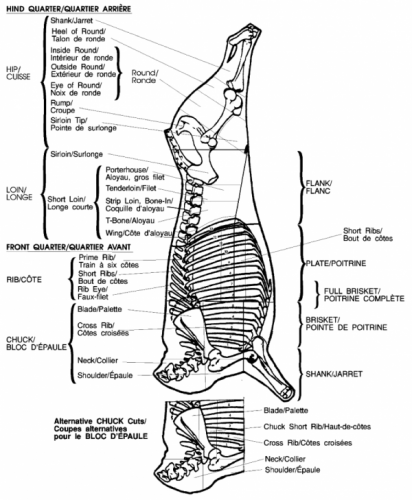

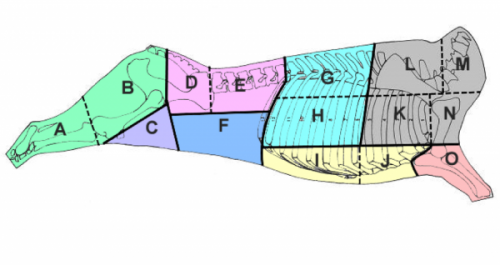

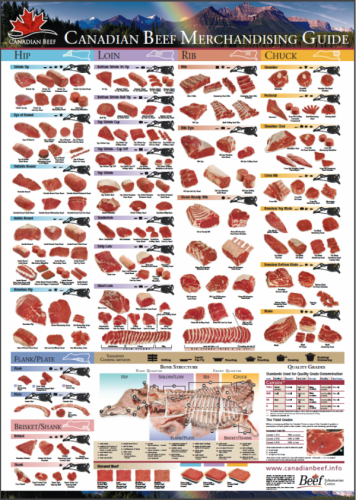

The grader assesses several characteristics of a beef carcass to determine quality (Table 6).

Table 6- Beef carcass quality factors | Beef Characteristics | Beef Carcass Quality Factors |

| Maturity (age) | The age of the animal affects tenderness. |

| Sex (male or female) | Pronounced masculinity in animals (males) affects meat colour and palatability (texture and taste). |

| Conformation (muscle shape) | Meat yield is influenced by the degree of muscling. |

| Fat (colour, texture, and cover) | Fat colour and texture (white as opposed to yellow) influence consumer acceptability, whereas fat cover affects meat yield. |

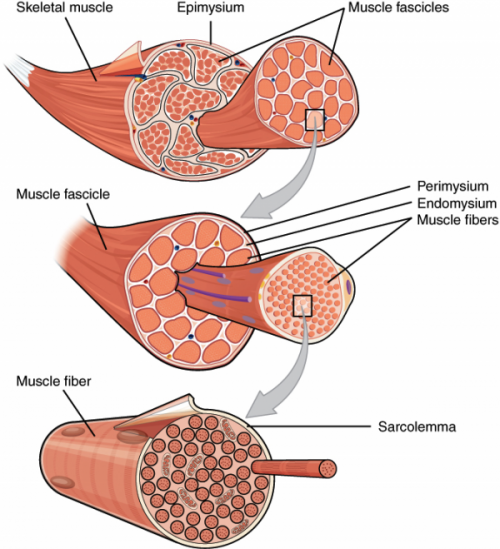

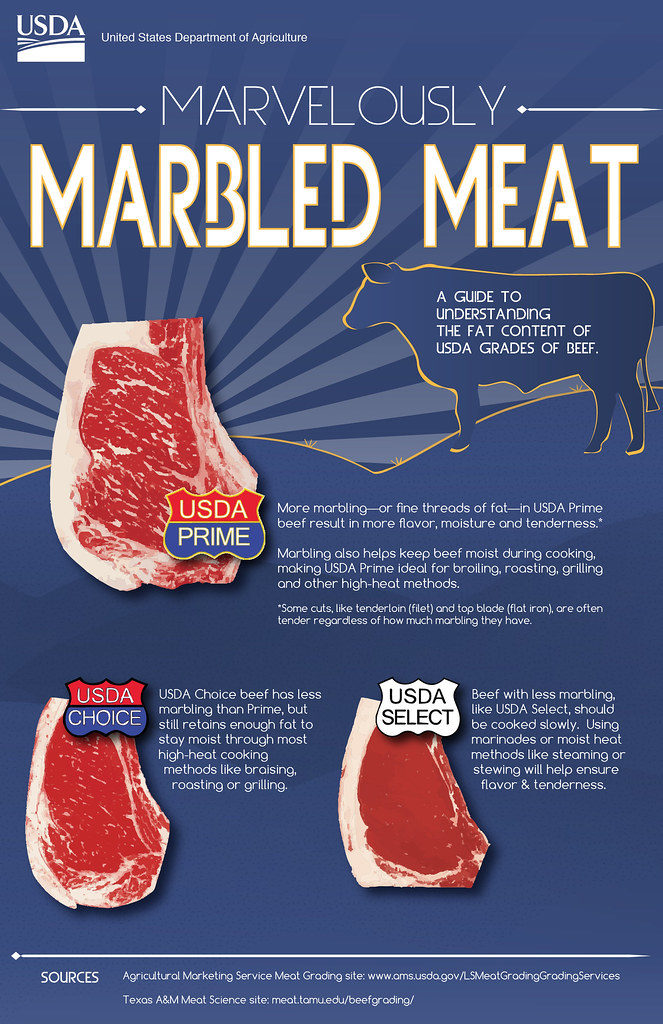

| Meat (colour, texture, and marbling) | Meat marbling affects quality: juiciness and tenderness. Colour and texture influence consumer acceptability. |

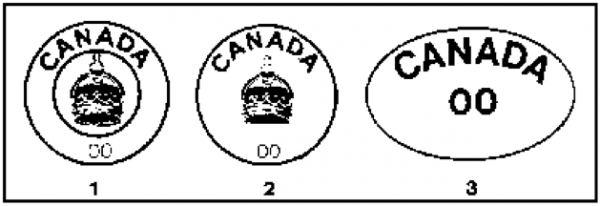

Table 7 lists the 13 grades of beef carcasses and the colour of each roller brand that is placed along the length of the carcass (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Rolled grade stamp on beef carcass.

Table 7- Beef grades | Red | Blue | Brown | Brown |

|---|

| Canada A | Canada B1 | Canada D1 | Canada E |

| Canada AA | Canada B2 | Canada D2 | |

| Canada AAA | Canada B3 | Canada D3 | |

| Canada Prime | Canada B4 | Canada D4 | |

Beef carcasses are graded in the A category using the following determinations:

- The age of the carcass is assessed (must be youthful).

- Fat levels are assessed by measuring with a special ruler on the left side of the carcass between the 12th and 13th ribs across the ribeye muscle at the 12th rib (the front quarter of beef).

- An additional assessment of the external fat cover of both sides is made. Grade A beef has a fat covering that is firm and white or slightly tinged with a reddish or amber colour and is not more than 2 mm in thickness at the measurement site.

- A muscle score is determined from a grid depending on the width and length of the ribeye muscle. Grade A beef has muscling that ranges from good with some deficiencies to excellent.

- Ten minutes after having been exposed, the ribeye muscle shows firm and bright red in colour (bloom).

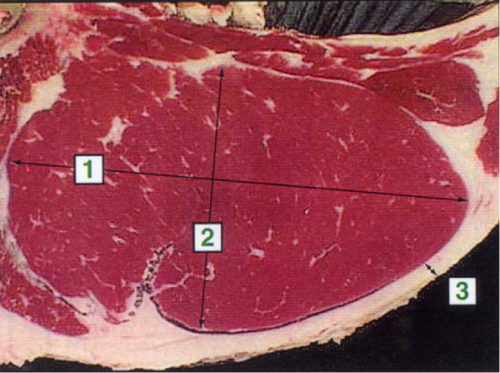

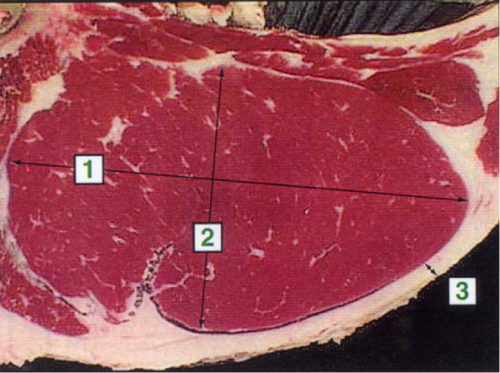

In addition, only A grade carcasses are assessed for the three lean meat yield classes. Yield grading is determined by measuring exterior fat thickness as well as the length and the width of the ribeye muscle at the 12th rib (Figure 15). The yield classes are indicated by a triangular-shaped stamp in red ink placed on the short-loin and rib sections of each side of the carcass. Yield classes are shown in Table 8.

Figure 15. Measuring yield for grading showing length (1), width (2), and fat thickness (3).

Table 8 – Yield classes and percentages | Yield class stamp | Meat yield |

| Canada 1 | 59% or higher |

| Canada 2 | 54% to 58% |

| Canada 3 | 53% or lower |

The A grades are assessed further to determine the marbling (intramuscular fat content), as shown in Table 9 and illustrated in Figure 16.

Table 9- Required marbling content of A grades | Grade | Marbling content |

| Canada A | At the least, traces, but less than a slight amount |

| Canada AA | At the least, a slight amount, but less than a small amount |

| Canada AAA | At the least, a small amount |

| Canada Prime | At the least, slightly abundant |

Figure 16. A grade marbling chart. Courtesy Beef Grading Centre

These marbling assessments offer the purchaser different levels of fat content to market. For example, some stores promote only AAA beef. A custom processor may want to dry age beef carcasses longer for his customers, but if he doesn’t want to have too high a waste factor (with fat), he may prefer to purchase AA or A beef. Restaurants may choose Canada Prime that shows a lot of marbling, has longer aging ability (wet aging, vacuum sealed), and therefore, in the long term, is more tender.

B grade beef (blue) is still good-quality meat for eating but doesn’t have the same consumer appeal as A grade. B grade beef is usually cheaper and doesn’t dry age as well as A grade. Table 10 provides B grade characteristics.

Table 10- Characteristics of B grade beef | Grade | Age | Muscling | Ribeye muscle | Marbling | Fat colour and texture | Fat measurement |

|---|

| B1 | Youthful | Firm, bright, and red | Devoid | Firm white or amber | Firm white or amber | Less than 2 mm |

| B2 | Youthful | Bright red | Bright red | Yellow | Yellow | No requirement |

| B3 | Youthful | Bright red | Bright red | White or amber | White or amber | No requirement |

| B4 | Youthful | Dark red | Bright red | No requirement | No requirement | No requirement |

D grade beef (brown) characteristics are shown in Table 11. D2 to D4 animals are used extensively in ground meat and in the manufacturing of sausage products.

Table 11- Characteristics of D grade beef | Grade | Age | Muscling | Ribeye muscle | Marbling | Fat colour and texture | Fat measurement |

|---|

| D1 | Mature (old) | Excellent | No requirement | No requirement | Firm white or amber | Less than 15 mm |

| D2 | Mature (old) | No requirement | No requirement | No requirement | White to Yellow | Less than 15 mm |

| D3 | Mature (old) | No requirement | No requirement | No requirement | No requirement | Less than 15 mm |

| D4 | Mature (old) | No requirement | No requirement | No requirement | No requirement | More than 15 mm |

E grade beef (brown) comes from youthful or mature (older) animals with pronounced masculinity, heavy shoulders, and lean and darker meat. These animals, often bulls and stags (unsuccessfully castrated bulls), are used extensively in the manufacturing of sausage products and ground meat.

Bison Grading

A new system for bison grading was developed in the 1990s. It is based on the beef grading system but takes into account the natural differences of the bison carcass. The official grading began in 1995, and on the basis of these standards the European Community (EC) approved bison sales to Europe. There are nine bison grades, which are evaluated for maturity, muscling, meat quality, and fat measurement. The grades are A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, C1, C2, D1, and D2.

Bison traditionally live longer than beef, and their bones and joints harden (ossify) more slowly. Furthermore, they are more heavily muscled in the shoulders and less muscled in the hindquarters than beef. These differences must be taken into account by the grader. Bison is now farmed in some provinces, including British Columbia and Alberta, and in several states in the United States. The product has become a popular alternative protein source, particularly with specialty meat markets and high-end restaurants.

Table 12 compares bison and beef grading.

Table 12- Differences between bison and beef grading | Bison | Beef |

| 9 grades | 13 grades |

| Knife ribbed between 11th and 12th ribs | Knife ribbed between the 12th and 13th ribs |

| 1 mm minimum fat cover for A grades | 4 mm minimum fat cover for A grades |

| Heavily muscled fronts | Heavily muscled hinds |

| 3 maturity divisions | 2 maturity divisions |

| More age in A grades than beef | Less age in A grades than bison |

| Grade stamped brown | Grade stamped red |

| 5 stamps per carcass side | 2 stamps per carcass side |

| Not ribbon branded | Ribbon branded |

| No marbling assessment | Marble assessed |

| 3 meat yield grades | 3 meat yield % for A grades |

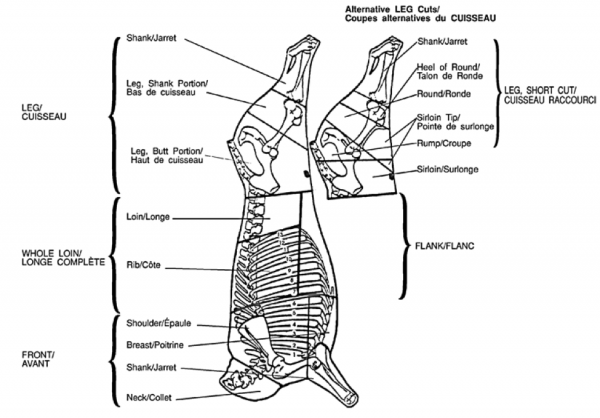

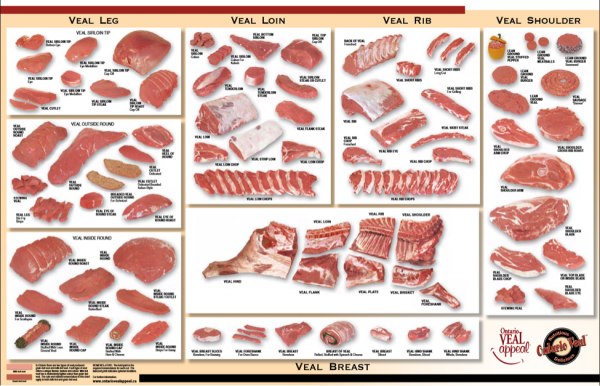

Veal Grading

Veal is meat from the young bovine born into the dairy industry. Most veal is sold through restaurants. However, today very few retail markets sell veal due to the low consumer demand.

Veal grading assesses both fat (creamy white) and good muscling as is done on beef, but it focuses even more on the colour of the flesh to determine the eventual grade. Veal is generally very tender due to its age and has a mild (some might even say bland) flavour, with little fat cover and marbling. There are several types of veal (Table 13).

Table 13- Veal types and descriptions | Veal Types | Age | Characteristics | Carcass Weight |

| Baby veal (Bob veal) | 3-30 days | Males, classified as “light,” sold whole for festive occasions and roasted whole | 9-27 kg (20-60 lb) |

| Vealers (light) | 1-3 months | Raised on milk with no restrictions on other types of feeds such as hay or grains | 36-68 kg (80-150 lb) |

| Nature (white veal) | Up to 5 months | Very expensive, white-pinkish flesh, no iron in diet, raised in pens, limited movement permitted | 82-109 kg (180-240 lb) |

| Calves (heavy) | Up to 5 months | Raised on milk and fed on grain-hay combinations; physically beginning to change from veal to beef | 68-136 kg (150-300 lb) |

Youthful bovine carcasses weighing less than 160 kg (32.2 lb) (hide off) are classified as veal by the Canadian beef grading program and are graded as shown in Table 14.

Table 14- Muscling requirements for veal grades | Grade | Requirements |

| Canada A1 to A4 | Carcasses with at least good muscling and some creamy white fat |

| Canada B1 to B4 | Carcasses with low to medium muscling and an excess of fat cover |

| Canada C1 and C2 | Carcasses failing to meet the requirements of Canada B |

All veal carcasses are then graded for meat colour. The veal grader uses a Minolta colour reflectance meter to do this. The carcasses are assigned a numerical value based on the objective measurement of meat colour. Then the carcasses are segregated into four colour classifications, based on the meter reading values. The most pale white colour range is given a grade of 1 and is assigned an A grade provided the kidney fat and muscling meet the A standard. As meat colour becomes more pink, grades of 2, 3, and 4 are assigned.

This scientific method of assessing meat colour is being continually refined. Research is now underway to develop a meat probe that will directly measure the level of meat pigment, which is the basis of all colour analysis. Should this method of colour determination be judged superior to the current methods, this new technology will be adopted. This process of muscle and colour grading ensures that purchasers of Canadian veal can specify their exact quality requirements.

Table 15 shows how the colour ranges are assigned the correct grade.

Table 15- Colour requirements for veal grading | Veal Grades | Veal Flesh Colour |

| Canada A1 | White 50 + |

| Canada A2 | Pink 40-49 |

| Canada A3 | Pale red 30-39 |

| Canada A4 | Red 0-29 |

| Canada B1 | Bright pink 50+ |

| Canada B2 | Pink 40-49 |

| Canada B3 | Pale red 30-39 |

| Canada B4 | Red 0-29 |

| Canada C1 | Pink or lighter 40 + |

| Canada C2 | Pale or dark red 39 or less |

Table 16 shows the criteria used to establish veal grades.

Table 16- Veal grading criteria | Grade | Kidney Fat | Muscling |

| A1-A4 | Covered with fat that is not excessive and is creamy white or pink tinged | At least good and free of depressions; 3 out of 4 of: 1. At least a straight profile for upper portion of leg 2. Loins wide and thick 3. Racks well covered 4. Shoulder points well covered |

| B1-B4 | Covered with fat deposits ranging from small to large | At least low to medium, some depressions; 3 out of 4 of: 1. Hip joints noticeable but not prominent 2. Loins with depressions 3. Racks sparsely covered with flesh 4. Shoulder points noticeable but not prominent |

| C1 and C2 | Extremely small deposits of fat on kidneys | Deficient to excellent |

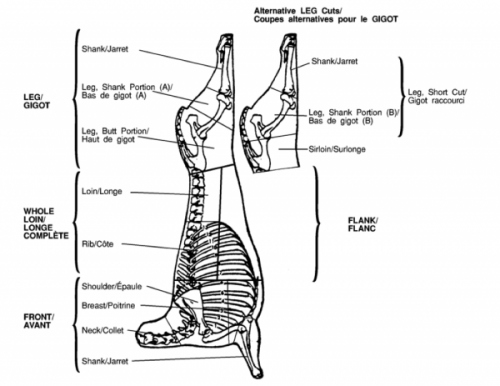

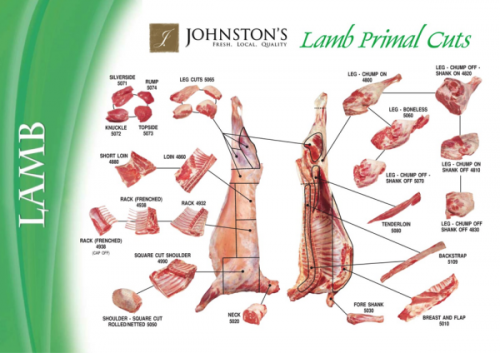

Lamb Grading

Lamb has become an increasingly popular protein in restaurants, local markets, and high-end stores in recent years. In addition, there is a growing need to supply the diverse ethnic trade market, which includes a growing Muslim community.

The lamb grading service is delivered by the Canadian Sheep Federation, which has been accredited by the CFIA to perform this function. The current system is voluntary and is designed to provide more information to producers and consumers. However, new technology is currently being developed to improve and speed up the current system at federal plants.

The seven lamb carcass grades are shown in Table 17, and the five mutton carcass grades are shown in Table 18.

Table 17- Lamb grades | Grades | Lamb Ribbon Brand Colour |

| Canada A1, A2, A3, A4 | Red |

| Canada B | Blue |

| Canada C1, C2 | Brown |

Table 18- Mutton grades | Grades | Mutton Ribbon Brand Colour |

| Canada D1, D2, D3, D4 | Black |

| Canada E | Black |

Currently in Canada, lamb (sheep under 12 months of age) and mutton (sheep 12 months of age or older) are graded by a generic system used in all regions. The measures to assess the grade are:

- Age, determined by the colour of the break joint on the front leg

- Weight

- Lean meat content and colour

- Fat content and colour

- Conformation or external shape of the carcass

These factors are further classified to determine a final grade using a formula integrating all the data collected, as noted in Table 19.

Table 19- Lamb grading criteria | Factors | Determining characteristics |

| Break joint colour | Purple, red (young), or white (old) |

| Meat colour | Designated a C only when the carcass exhibits extremely dark meat (old) |

| Sex | Male or female |

| Fat cover | ● + (plus sign) for excessive covering ● N for normal covering ● — (minus sign) for deficient covering |

Conformation (shape), which then determines

a muscle score of 1 to 5 | ● + (plus sign) for good to excellent ● N for medium to good ● — (minus sign) for marked deficiencies ● 1 indicates extreme deficiencies ● 5 indicates excellent muscling |

| Exterior fat depth (EFD) | Actual fat depth as measured by a ruler over the 12th rib 11 cm from carcass back midline |

| Fat colour | Designated with a Y when a carcass exhibits yellow fat |

| Weight | Indicated by warm carcass weight (WCW) |

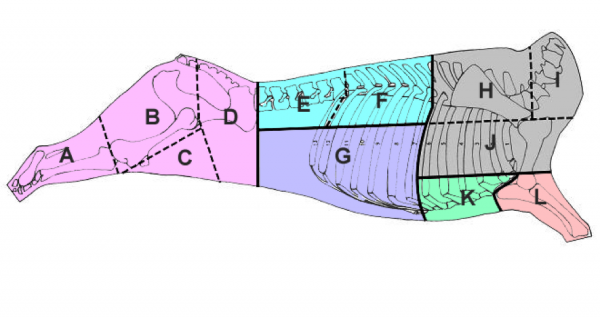

Pork Grading

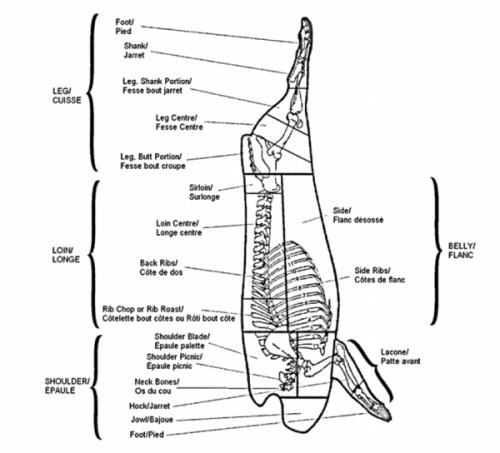

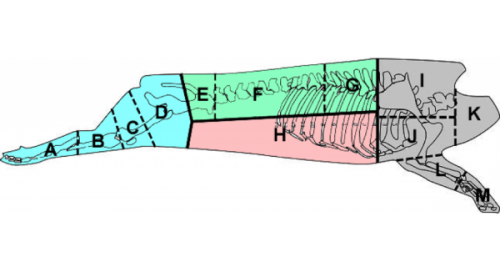

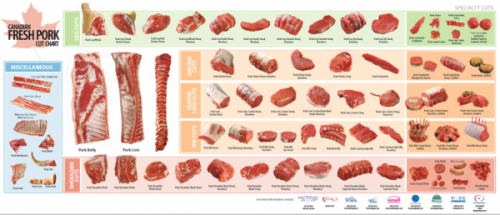

Requirements for pork grading are established under the authority of the Canada Agricultural Products Act and the Livestock and Poultry Carcass Grading Regulations. In commercial agriculture, pigs raised for food (pork) are usually referred to as hogs. Once the carcasses have been graded, the meat is always referred to as pork.

Hogs are popular farm animals because they mature more quickly than other animals and are ready for slaughter at approximately six months of age. Hogs must be handled very carefully during the harvesting process as they are easily stressed. To offset some of the stress they are electrically stunned (which is faster and requires quicker bleeding time) or gassed in federal plants in a special chamber that gradually removes the oxygen and then introduces carbon dioxide to ensure a painless death and means less rush prior to bleeding.

Pork from youthful hogs is very tender due to the absence of heavy connective tissue. Unlike beef, pork does not need to be aged very long. The flesh has a pinkish colour, a fine texture, and very greasy white fat that enhances the flavour of the meat. Pork is very popular in North America and other Western and European countries and is a popular item on restaurant menus; in addition, it is considered a diverse and profitable product that is increasingly in demand in manufactured products, such as the many varieties of sausages and cured products available today.

Canada has several major pork marketing agencies, such as the Canadian Pork Council and Canada Pork International, as well as provincial organizations, such as Alberta Pork and BC Pork, that promote and monitor the industry. All commercial hog carcasses are either federally or provincially inspected.

There are 12 grades of hog carcasses with criteria outlined in Table 20.

Table 20- Hog (pork) grades | Hog Grade Classes | # of Grades | Hog Criteria |

| Canada Yield with 7 classes | 1 | Weight must be 40 kg (88 lb) or more |

| Canada Emaciated | 1 | Weight must be 40 kg (88 lb) or less |

| Canada Ridgling | 1 | Has one or two undescended testicles or has both male and female sex organs |

| Canada Sow 1-6 | 6 | Must be a sow with the required back fat levels, good muscling, straight to convex profile, and barely visible shoulder joints |

| Canada Sow 7 | 1 | Must be a sow deficient in muscling and finish |

| Canada Stag | 1 | A mature porcine animal, castrated before slaughter, and exhibiting pronounced masculinity at time of slaughter |

| Canada Boar | 1 | Must be a male carcass with one or more testicles but not a carcass of a ridgling |

Modern technology provides a quick and accurate method for grading hogs at federally inspected plants:

- An electronic probe is inserted between the third and fourth ribs on the left side of the carcass. The needle has a sensor light on the end.

- As the needle is withdrawn from the probe site, it measures meat thickness and fat levels.

- These measurements are fed into a computer, which generates a yield class estimating percentage of lean meat.

This method of grading hogs is used to establish producer payments, which are automatically sent to the farmer’s bank account.

An overview of the grading process using an electronic probe can be found at https://www.westernhogexchange.com/about/marketing/GradingGrids.aspx

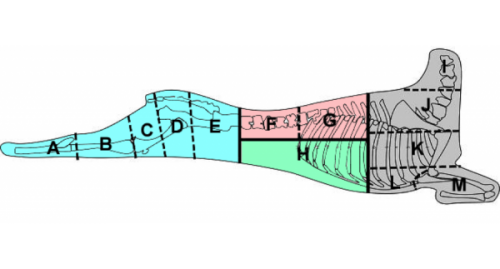

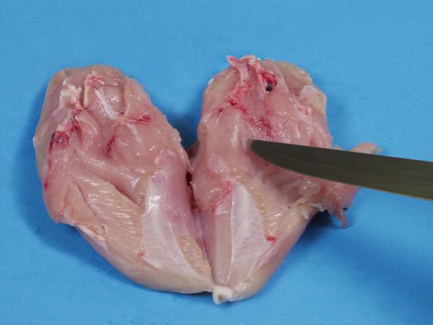

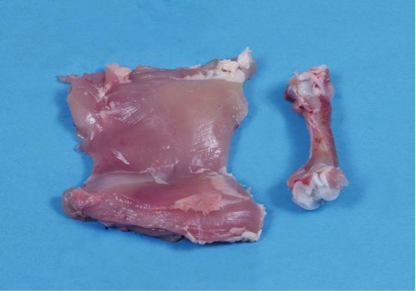

Poultry Grading

All commercial poultry for sale must be inspected at federally or provincially designated poultry harvesting plants and show proof of inspection with a stamp similar to what is shown on beef carcasses: a round stamp with a crown in the centre, the word “Canada” above, and the plant registration number below.

Poultry harvesting includes electrical stunning, with the bird’s head touching either a charged wand or a charged water bath prior to bleeding. The carcasses are then scalded to loosen the feathers, after which they pass through a fast-rotating automatic feather-plucking drum. This is followed by the evisceration process and meat inspection. The carcass is then passed through a rapid air-chilling system to cool the carcass as quickly as possible. Air-cooled poultry has a much longer shelf life (approximately 5 to 10 days) compared to the shelf life of a poultry carcass that has just been allowed to cool naturally after harvesting and processing.

Poultry graders assess the carcasses for several criteria. Those for A grade poultry are shown in Table 21.

Table 21- A grade poultry | Poultry Grading Factors | Criteria for A Grade Poultry |

| Conformation (shape) | ● Refers to the physical points on the outside of the bird ● A grade birds must have normal conformation, including a plump body, stocky legs, and a well-dressed body ● NO missing parts such as wings ● NO crooked keel bone ● NO broken bones, bruises, or cysts |

| Fleshing (desired quality) | ● Refers to the amount and distribution of meat ● A grade birds must have moderately long and broad plump and firm breast meat ● Short, plump legs |

| Fat covering | ● A grade birds have an even covering of fat under the skin ● Good fat cover indicates yellowish or cream-coloured skin ● A blemish or reddish tinge beneath the skin indicates poor fat covering |

| Bones | ● A grade birds must have a soft and pliable keel bone cartilage ● Joints are loose but not springy |

| Carcass dressing | ● A grade birds are free of pin feathers ● Pin feathers will lower carcass saleability |

There are three grades of processed poultry. The grade stamp is a maple leaf with the grade’s respective colour and the appropriate grade in the centre (Table 22). These grades are used for chickens but are also used for:

- Capons

- Rock Cornish hen

- Mature chicken

- Old rooster

- Young and mature turkey

- Young and mature duck

- Young and mature goose

Table 22- Poultry grades | Poultry Grades | Poultry Grade Colour | Poultry Criteria |

| Canada A | Red | See Table 21 |

| Canada Utility | Blue | - Insufficient fat

- Not more than the following missing parts:

- wings, tail, one leg (including the thigh or both drumsticks)

- small areas of flesh from the carcass

- skin not more than half of the area of the breast

- No dislocated or broken bones other than wings or legs

- No prominent discolourations exceeding a certain size on breast or elsewhere on carcass

|

| Canada C | Brown | Mature or older poultry requiring moist heat cooking |

Types of Chicken and Turkey

Chickens are also categorized according to age and size, the most common being frying chicken (also called fryers or broilers). These are usually 6 to 8 weeks old and weigh approximately 1.1 to 1.6 kg (2 1/2 to 3 1/2 lb). Roasting chickens or roasters are young birds over 8 weeks, but usually between 12 and 20 weeks old, that weigh over 2.2 kg (5 lb). Rock Cornish hens are small chickens that weigh between 500 g and 900 kg (1 to 2 lb). Very young chickens, called poussin, are less than 500 g (1 lb). A Capon is a large castrated male that weighs 2.7 to 3.6 kg (6 to 8 lb), and a stewing hen or fowl is an older bird, usually female, over 10 months of age and weighing 2.2 to 3.2 kg (5 to 7 lb).

Turkeys are classified by age only. Young turkeys are approximately 24 weeks of age. Mature turkeys are over 24 months of age.