Figure 15.1. The elephant-headed Ganesh, remover of obstacles, finds a home in Vancouver. Late modern society is characterized by strange and unexpected blendings of the sacred and profane. (Photo courtesy of Rob Brownie)

Learning Objectives

15.1. The Sociological Approach to Religion

- Explain the difference between substantial, functional, and family resemblance definitions of religion.

- Describe the four dimensions of religion: Belief, ritual, experience, and community.

- Understand classifications of religion, like animism, polytheism, monotheism, and atheism.

- Differentiate between the five world religions.

- Explain the differences between various types of religious organizations: Churches, ecclesia, sects, and cults.

15.2. Sociological Explanations of Religion

- Examine the nature of sociological explanations of religion.

- Compare and contrast theories on religion — Marx, Durkheim, Weber, Berger, Stark, Daly, and Woodhead.

15.3. Religion and Social Change

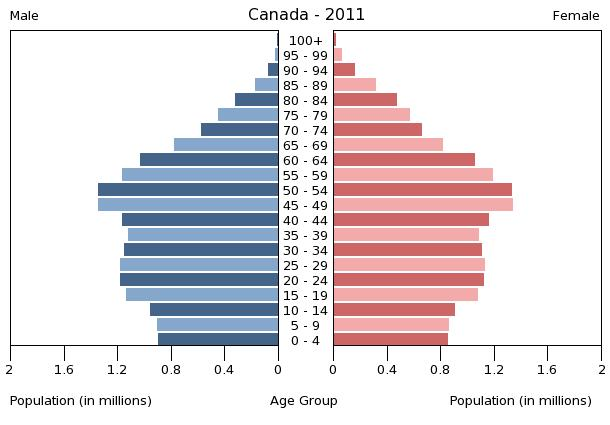

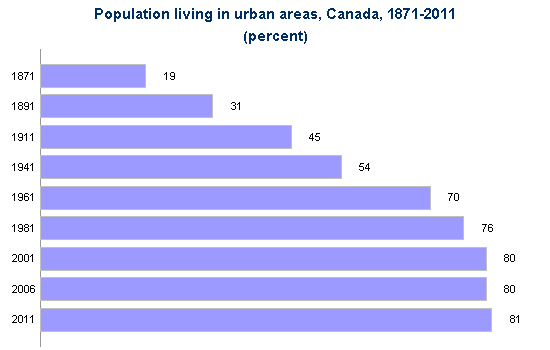

- Describe current global and Canadian trends of secularization and religious belief.

- Describe the current religious diversity of Canada and its implications for social policy.

- Explain the development and the sources of new religious movements.

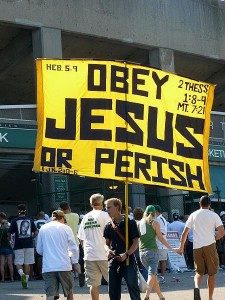

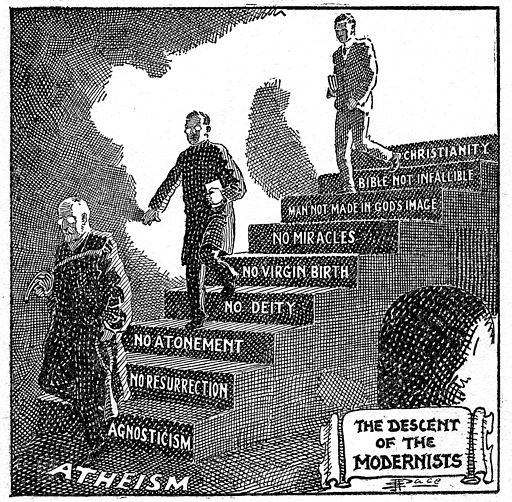

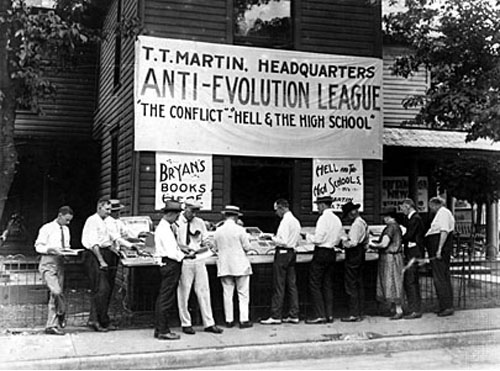

15.4. Contemporary Fundamentalist Movements

- Outline the social and political issues associated with fundamentalist movements.

- Define the family resemblance between fundamentalisms in different religious traditions.

- Describe the process of fundamentalist radicalization from a sociological perspective.

- Explain the basis of contemporary issues of science and faith.

List of Contributors to Chapter 15: Religion

Introduction to Religion

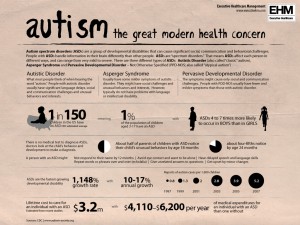

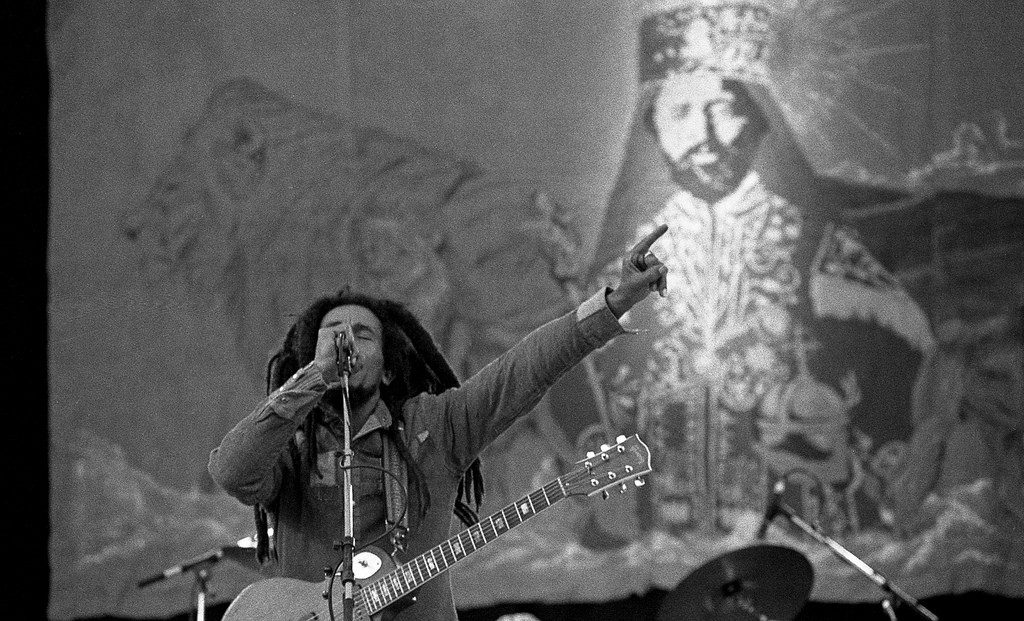

15.2. Religion is defined by its unique ability to provide individuals with answers to the ultimate questions of life, death, existence. and purpose. (photo courtesy of Ras67/Wikimedia)

It is commonly said that there are only two guarantees in life — death and taxes — but what can be more taxing than the prospect of one’s own death? Ceasing to exist is an overwhelmingly terrifying thought and it is one which has plagued individuals for centuries. This ancient stressor has been addressed over time by a number of different religious explanations and affirmations. Arguably, this capacity to provide answers for fundamental questions is what defines religion. For instance, under Hindu belief one’s soul lives on after biological death and is reborn in a new body. Under Christian belief one can expect to live in a heavenly paradise once one’s time runs out on earth. These are just two examples, but the extension of the self beyond its physical expiration date is a common thread in religious texts.

These promises of new life and mystifying promise lands are not simply handed out to everyone, however. They require an individual to faithfully practice and participate in accordance to the demands of specific commandments, doctrines, rituals, or tenants. Furthermore, despite one’s own faith in the words of an ancient text, or the messages of a religious figure, an individual will remain exposed to the trials, tribulations, and discomforts that exist in the world. During these instances a theodicy — a religious explanation for such sufferings — can help keep one’s faith by providing justification as to why bad things happen to good, faithful people. Theodicy is an attempt to explain or justify the existence of bad things or instances that occur in the world, such as death, disaster, sickness, and suffering. Theodicies are especially relied on to provide reason as to why a religion’s God (or God-like equivalent) allows terrible things to happen to good people.

Is there truly such a thing as heaven or hell? Can we expect to embody a new life after death? Are we really the creation of an omnipotent and transcendent Godly figure? These are all fascinating ontological questions — i.e., questions that are concerned with the nature of reality, our being and existence — and ones for which different religious traditions have different answers. For example, Buddhists and Taoists believe that there is a life force that can be reborn after death, but do not believe that there is a transcendent creator God, whereas Christian Baptists believe that one can be reborn once, or even many times, within a single lifetime. However, these questions are not the central focus of sociologists. Instead sociologists ask about the different social forms, experiences, and functions that religious organizations evoke and promote within society. What is religion as a social phenomenon? Why does it exist? In other words, the “truth” factor of religious beliefs is not the primary concern of sociologists. Instead, religion’s significance lies in its practical tendency to bring people together and, in notable cases, to violently divide them. For sociologists, it is key that religion guides people to act and behave in particular ways. How does it do so?

Regardless if one personally believes in the fundamental values, beliefs, and doctrines that certain religions present, one does not have to look very far to recognize the significance that religion has in a variety of different social aspects around the world. Religion can influence everything from how one spends their Sunday afternoon – -singing hymnals, listening to religious sermons, or refraining from participating in any type of work — to providing the justification for sacrificing one’s own life, as in the case in the Solar Temple mass suicide (Dawson & Thiessen, 2014). Religious activities and ideals are found in political platforms, business models, and constitutional laws, and have historically produced rationales for countless wars. Some people adhere to the messages of a religious text to a tee, while others pick and choose aspects of a religion that best fit their personal needs. In other words, religion is present in a number of socially significant domains and can be expressed in a variety of different levels of commitment and fervour.

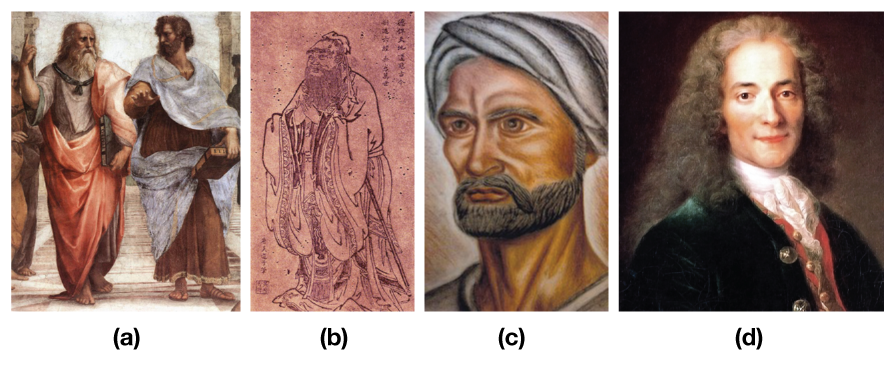

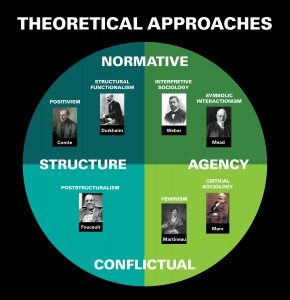

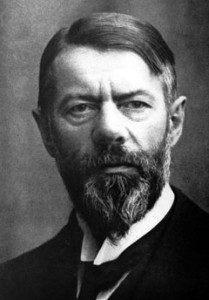

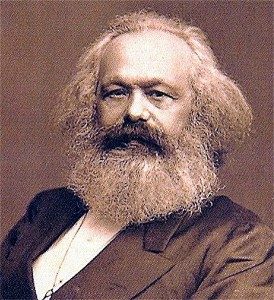

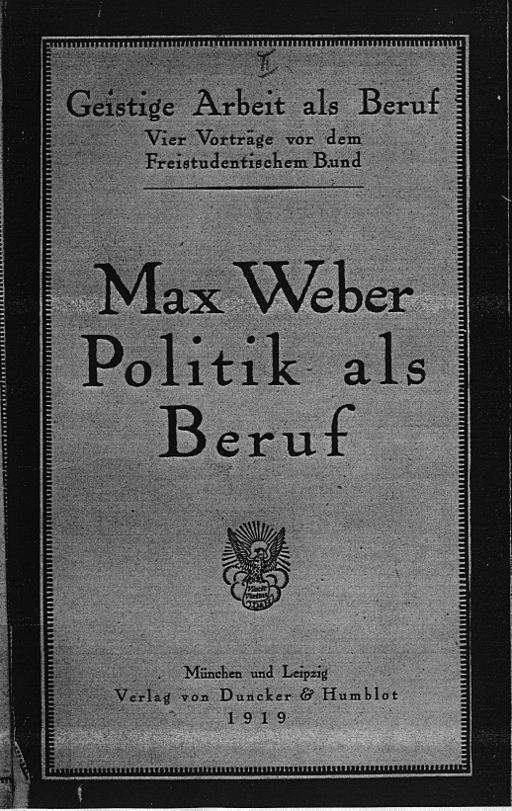

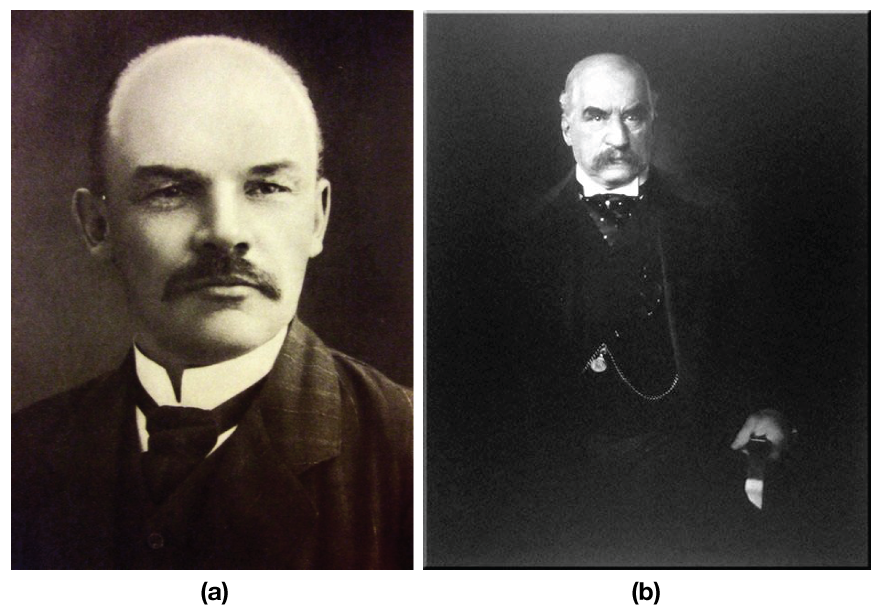

In this chapter, classical social theorists Karl Marx, Émile Durkheim, and Max Weber provide the early insights that have come to be associated with the critical, functionalist, and interpretive perspectives on religion in society. Interestingly, each of them predicted that the processes of modern secularization would gradually erode the significance of religion in everyday life. More recent theorists like Peter Berger, Rodney Stark (feminist), and John Caputo take account of contemporary experiences of religion, including what appears to be a period of religious revivalism. Each of these theorists contribute uniquely important perspectives that describe the roles and functions that religion has served society over time. When taken altogether, sociologists recognize that religion is an entity that does not remain stagnant. It evolves and develops alongside new intellectual discoveries and expressions of societal, as well as individual, needs and desires.

15.3. Pope Francis was named Time magazine’s “Person of the Year” in 2013, where he was identified as “poised to transform a place [i.e., the Vatican] that measures change by the century” (Chua-Eoan & Dias 2013). What types of impact can the words of a religious leader have on society today? (Photo courtesy of Edgar Jiménez/Flickr).

A case in point would be the evolution of belief in the Catholic Church. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Roman Catholic Church responded to the challenges brought forth by secularization, scientific reasoning, and rationalist methodologies with Pope Pius X’s encyclical Pascendi dominici gregis (1907). This letter was circulated among all of the Catholic churches and identified the new “enemy of the cross” as the trend towards modernization. A secretive “Council of Vigilance” was established in each diocese to purge church teachings of the elements of modernism. The true faith “concerns itself with the divine reality which is entirely unknown to science.”

However, in the 21st century, the Catholic Church appears to be adapting its attitudes towards modernization. The 266th Roman Catholic Pope, Pope Francis, has made public statements such as, “If a person is gay and seeks God and has good will, who am I to judge?” (Reuters, 2013) and “We cannot limit the role of women in the Church to altar girls or the president of a charity, there must be more” (BBC News, 2013). These statements seem to align the Church’s position with contemporary attitudes towards homosexuality and gender. Pope Francis has also addressed contemporary issues of climate change. At the 2015 U.N. climate conference in Paris, France, he stated that “[e]very year the problems are getting worse. We are at the limits. If I may use a strong word I would say that we are at the limits of suicide” (Pullella, 2015).

15.1. The Sociological Approach to Religion

From the Latin religio (respect for what is sacred) and religare (to bind, in the sense of an obligation), the term religion describes various systems of belief and practice concerning what people determine to be sacred or spiritual (Durkheim, 1915/1964; Fasching and deChant, 2001). Throughout history, and in societies across the world, leaders have used religious narratives, symbols, and traditions in an attempt to give more meaning to life and to understand the universe. Some form of religion is found in every known culture, and it is usually practiced in a public way by a group. The practice of religion can include feasts and festivals, God or gods, marriage and funeral services, music and art, meditation or initiation, sacrifice or service, and other aspects of culture.

Defining Religion

Figure 15.4. Santo Daime is a syncretic religion founded in Brazil in the 1930s that draws on elements of Catholicism, spiritualism, and Indigenous animism. The entheogenic brew Ayahuasca (or “Daime”), shown here in bottles, is used in religious rituals that often last many hours. (Photo courtesy of Aiatee/Wikimedia Commons)

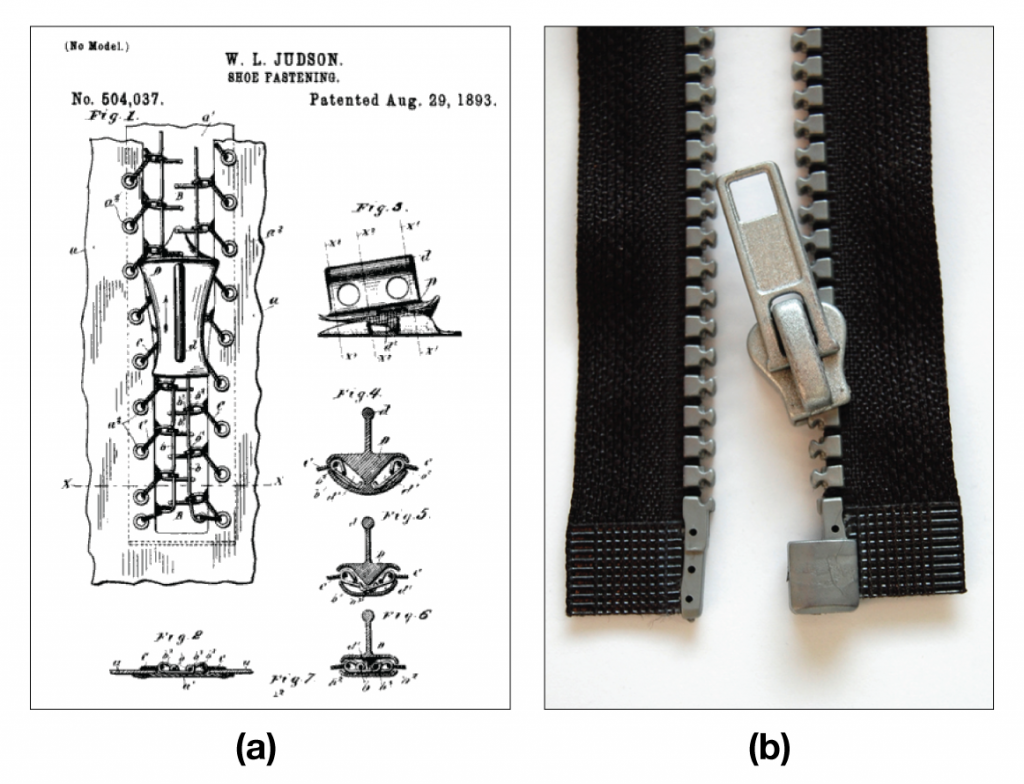

There are three different ways of defining religion in sociology — substantial definitions, functional definitions, and family resemblance definitions — each of which has consequences for what counts as a religion, and each of which has limitations and strengths in its explanatory power (Dawson and Thiessen, 2014). The problem of defining religion is not without real consequences, not least for questions of whether specific groups can obtain legal recognition as religions. In Canada there are clear benefits to being officially defined as a religion in terms of taxes, liberties, and protections from persecution. Guarantees of religious freedom under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms stem from whether practices or groups are regarded as legitimately religious or not. What definitions of religion do we use to decide these questions?

For example, the Céu do Montréal was established in 2000 as a chapter of the Brasilian Santo Daime church (Tupper, 2011). One of the sacraments specified in church doctrine and used in ceremonial rituals is ayahuasca, a psychedelic or entheogenic “tea” that induces visions when ingested. It has to be imported from the Amazon where its ingredients are found. But because it contains N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids, it is a controlled substance under Canadian law. Importing and distributing it constitute trafficking and are subject to criminal charges. Nevertheless because of ayahuasca’s role as a sacrament in the church’s religious practice, Céu do Montréal was able to apply to the Office of Controlled Substances of Health Canada for a legal, Section 56 exemption to permit its lawful ceremonial use. Other neo-Vegetalismo groups who use ayahuasca in traditional Amazonian healing ceremonies in Canada, but do not have affiliations with a formal church-like organization, are not recognized as official religions and, therefore, their use of ayahuasca remains criminalized and underground.

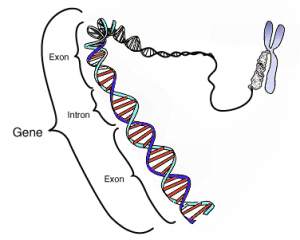

The problem of any definition of religion is to provide a statement that is at once narrow enough in scope to distinguish religion from other types of social activity, while taking into account the wide variety of practices that are recognizably religious in any common sense notion of the term. Substantial definitions attempt to delineate the crucial characteristics that define what a religion is and is not. For example, Sir Edward Tylor argued that “a minimum definition of Religion [is] the belief in spiritual beings” (Tylor, 1871, cited in Stark, 1999), or as Sir James Frazer elaborated, “religion consists of two elements… a belief in powers higher than man and an attempt to propitiate or appease them” (Frazer, 1922, cited in Stark, ibid.). These definitions are strong in that they identify the key characteristic — belief in the supernatural — that distinguishes religion from other types of potentially similar social practice like politics or art. They are also easily and simply applied across societies, no matter how exotic or different the societies are. However, the problem with substantial definitions is that they tend to be too narrow. In the case of Tylor’s and Frazer’s definitions, emphasis on belief in the supernatural excludes some forms of religion like Theravadan Buddhism, Confucianism, or neo-paganism that do not recognize higher, spiritual beings, while also suggesting that religions are primarily about systems of beliefs, (i.e., a cognitive dimension of religion that ignores the emotive, ritual, or habitual dimensions that are often more significant for understanding actual religious practice).

On the other hand, functional definitions define religion by what it does or how it functions in society. For example, Milton Yinger’s definition is: “Religion is a system of beliefs and practices by means of which a group struggles with the ultimate problems of human life” (Yinger, 1970, cited in Dawson and Thiessen, 2014). A more elaborate functional definition is that of Mark Taylor (2007): religion is “an emergent, complex, adaptive network of symbols, myths, and rituals that, on the one hand, figure schemata of feeling, thinking, and acting in ways that lend life meaning and purpose and, on the other, disrupt, dislocate, and disfigure every stabilizing structure.” These definitions are strong in that they can capture the many forms that these religious problematics or dynamics can take — encompassing both Christianity and Theravadan Buddhism for example — but they also tend to be too inclusive, making it difficult to distinguish religion from non-religion. Is religion for example the only means by which social groups struggle with the ultimate problems of human life?

The third type of definition is the family resemblance model in which religion is defined on the basis of a series of commonly shared attributes (Dawson and Thiessen, 2014). The family resemblance definition is based on the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s ordinary language definition of games (Wittgenstein, 1958). Games, like religions, resemble one another — we recognize them as belonging to a common category — and yet it is very difficult to decide precisely and logically what the rule is that subsumes tiddly winks, solitaire, Dungeons and Dragons, and ice hockey under the category “games.” Therefore the family resemblance model defines a complex “thing” like religion by listing a cluster of related attributes that are distinctive and shared in common by different versions of that thing, while noting that not every version of the thing will have all of the attributes. The idea is that a family – even a real family – will hold a number of, say, physiological traits in common, which can be used to distinguish them from other families, even though each family member is unique and any particular family member might not have all them. You can still tell that the member belongs to the family and not to another because of the traits he or she shares.

It is also possible to define religion in terms of a cluster of attributes based on family resemblance. This cluster includes four attributes: particular types of belief, ritual, experience, and social form. This type of definition has the capacity to capture aspects of both the substantive and functional definitions. It can be based on common sense notions of what religion is and is not, without the drawback of being overly exclusive. While the thing, “religion,” itself becomes somewhat hazy in this definition, it does permit the sociologist to examine and compare religion based on these four dimensions while remaining confident that he or she is dealing with the same phenomenon.

The Four Dimensions of Religion

The incredible amount of variation between different religions makes it challenging to decide upon a concrete definition of religion that applies to all of them. In order to facilitate the sociological study of religion it is helpful to turn our attention to four dimensions that seem to be present, in varying forms and intensities, in all types of religion: belief, ritual, spiritual experience, and unique social forms of community (Dawson & Thiessen, 2014).

The first dimension is one that comes to mind for most Canadians when they think of religion, some systematic form of beliefs. Religious beliefs are a generalized system of ideas and values that shape how members of a religious group come to understand the world around them (see Table 15.1 and 15.2 below). They define the cognitive aspect of religion. These beliefs are taught to followers by religious authorities, such as priests, imams, or shamen, through formal creeds and doctrines as well as more informal lessons learned through stories, songs, and myths. A creed outlines the basic principles and beliefs of a religion, such The Nicene creed in Christianity (“I believe in the father, the son and the holy ghost…”), which is used in ceremonies as a formal statement of belief (Knowles, 2005).

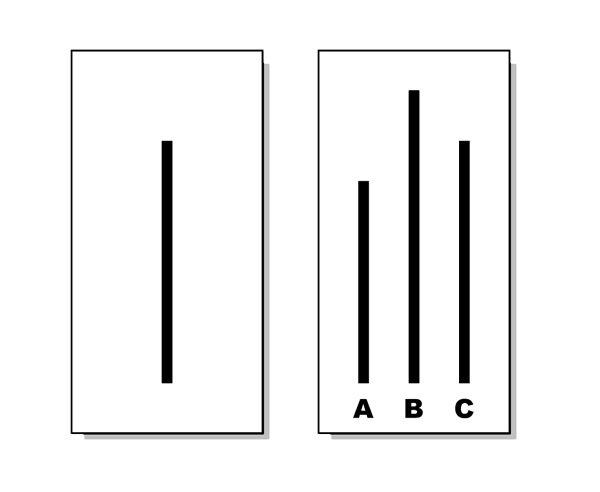

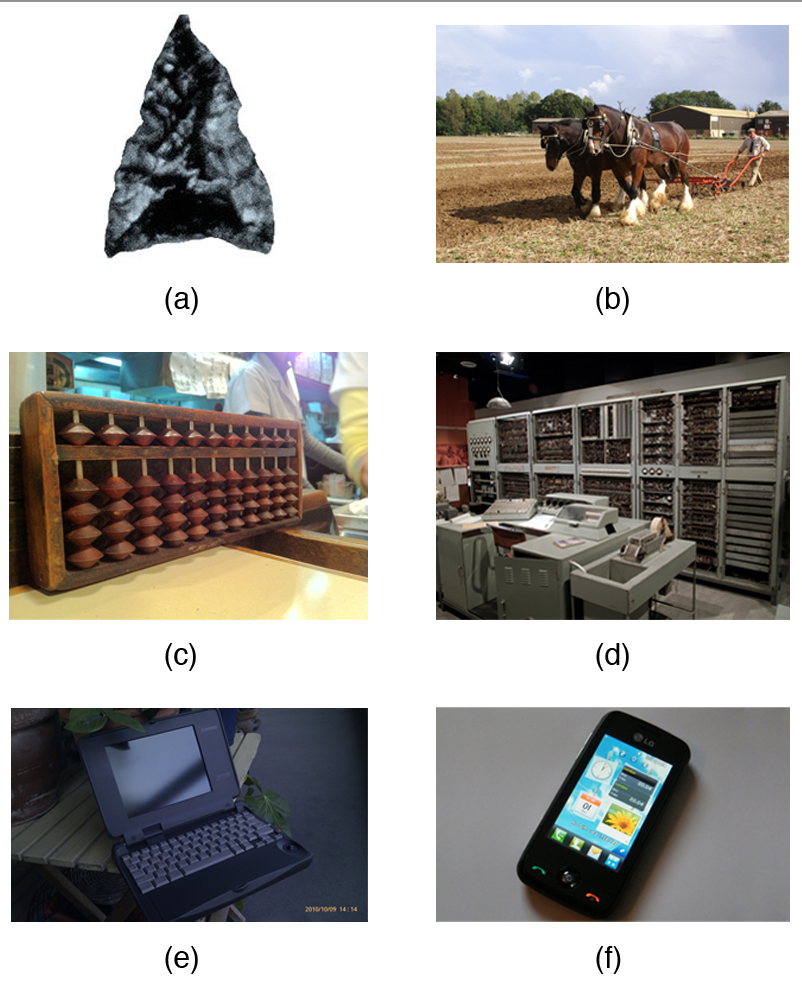

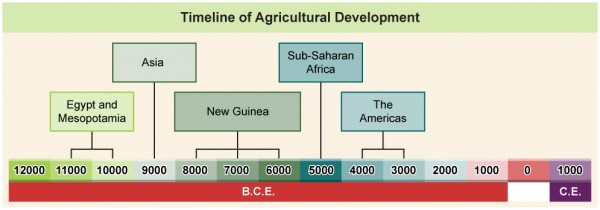

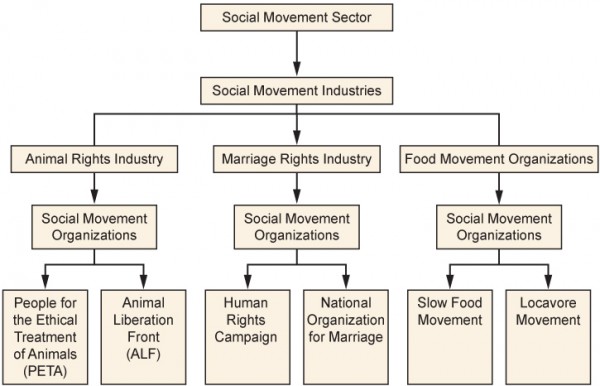

Table 15.1. One way scholars have categorized religions is by classifying what or who they hold to be divine. | Religious Classification | What/Who Is Divine | Example |

|---|

| Polytheism | Multiple gods | Hinduism, Ancient Greeks and Romans |

| Monotheism | Single god | Judaism, Islam, Christianity |

| Atheism | No deities | Atheism, Buddhism, Taoism |

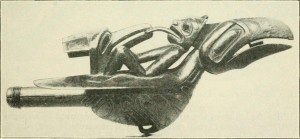

| Animism | Nonhuman beings (animals, plants, natural world) | Indigenous nature worship, Shinto |

Belief systems provide people with certain ways of thinking and knowing that help them cope with ultimate questions that cannot be explained in any other way. One example is Weber’s (1915) concept of theodicy — an explanation of why, if a higher power does exist, good and innocent people experience misfortune and suffering. Weber argues that the problem of theodicy explains the prevalence of religion in our society. In the absence of other plausible explanations of the contradictory nature of existence, religious theodicies construct the world as meaningful. He gives several examples of theodicies — including karma, where the present actions and thoughts of a person have a direct influence on their future lives, and predestination, the idea that all events are an outcome God’s predetermined will.

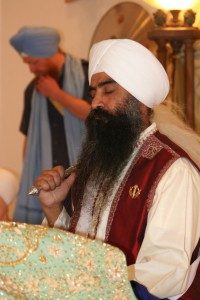

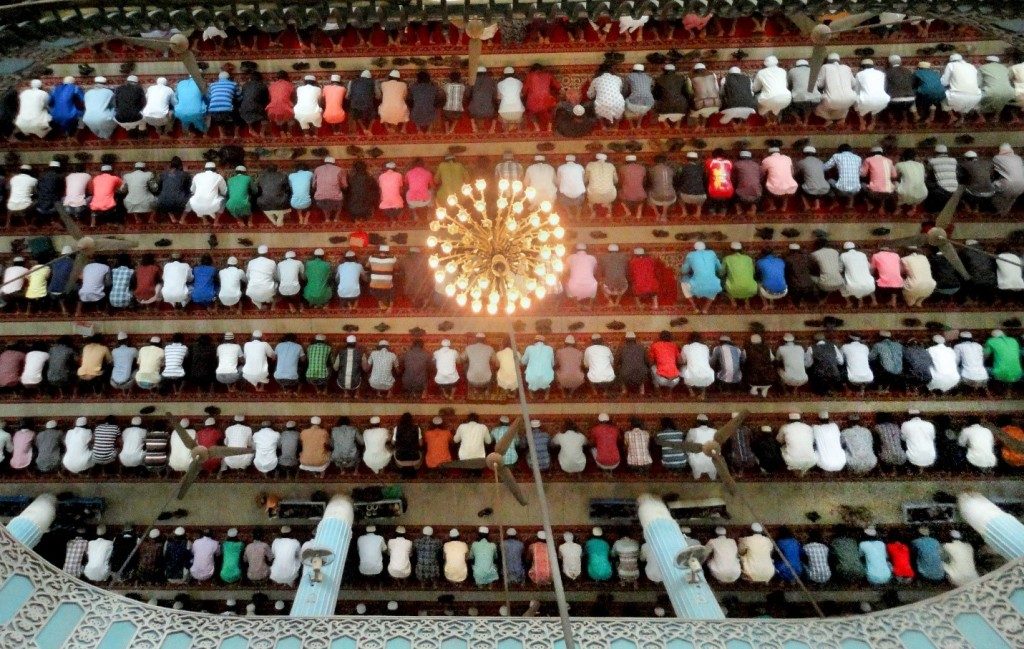

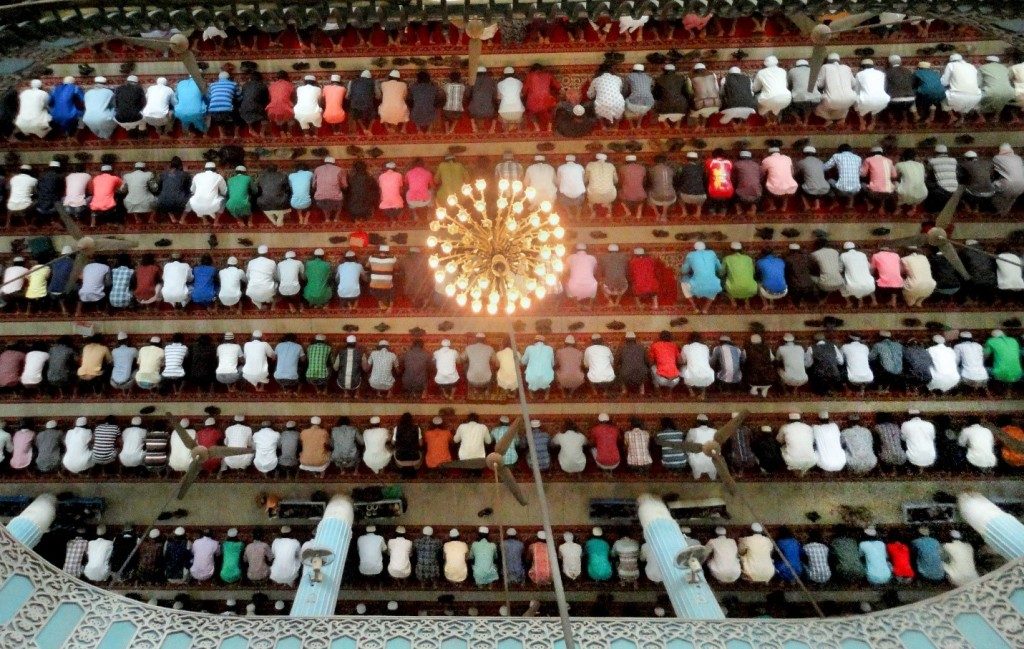

Figure 15.5. Prayer is a ritualistic practice or invocation common to many religions in which a person seeks to attune themselves with a higher order. One of the five pillars of Islam requires Salat, or five daily prayers recited while facing the Kaaba in Mecca. (Photo courtesy of Shaeekh Shuvro/Flickr)

The second dimension, ritual, functions to anchor religious beliefs. Rituals are the repeated physical gestures or activities, such as prayers and mantras, used to reinforce religious teachings, elicit spiritual feelings, and connect worshippers with a higher power. They reinforce the division between the sacred and the profane by defining the intricate set of processes and attitudes with which the sacred dimension of life can be approached.

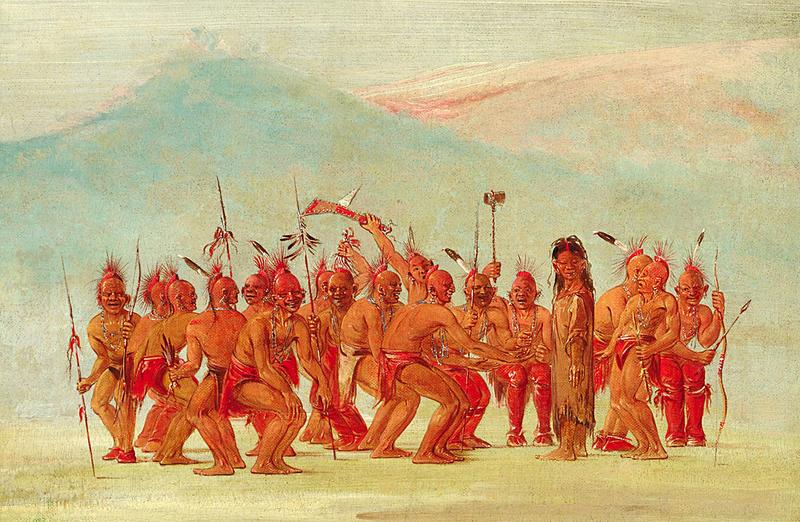

A common type of ritual is a rite of passage, which marks a person’s transition from one stage of life to another. Examples of rites of passage common in contemporary Canadian culture include baptisms, Bar Mitzvahs, and weddings. They sacralize the process of identity transformation. When these rites are religious in nature, they often also mark the spiritual dangers of transformation. The Sun Dance rituals of many Native American tribes are rites of renewal which can also act as initiation-into-manhood rites for young men. They confer great prestige onto the pledgers who go through the ordeal, but there is also the possibility of failure. The sun dances last for several days, during which young men fast and dance around a pole to which they are connected by rawhide strips passed through the skin of the chest (Hoebel, 1978). During their weakened state, the pledgers are neither the person they were, nor yet the person they are becoming. Friends and family members gather in the camp to offer prayers of support and protection during this period of vulnerable “liminality.” Overall, rituals like these function to bring a group of people (although not necessarily just religious groups) together to create a common, elevated experience that increases social cohesion and solidarity.

From a psychological perspective, rituals play an important role in providing practitioners with access to spiritual “powers” of various sorts. In particular, they can access powers that both relieve or induce anxieties within a group depending on the circumstances. In relieving anxieties, religious rituals are often present at times when people face uncertainty or chance. In this sense they provide a basis of psychological stability. A famous example of this is Malinowski’s study of the Trobriand Islanders of New Guinea (1948). When fishing in the sheltered coves of the islands very little ritual was involved. It was not until fishermen decided to venture into the much more dangerous open ocean in search of bigger and riskier catches that a rigorous set of religious rituals were invoked, which worked to subdue the fears of not only the fisherman but the rest of the villagers.

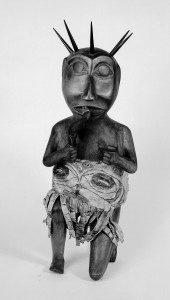

In contrast, rituals can also be used to create anxieties that keep people in line with established norms. In the case of taboos, the designation of certain objects or acts as prohibited or sacred creates an aura of fear or anxiety around them. The observance of rituals is used to either prevent the transgression of taboos or to return society to normal after taboos have been transgressed. For example, early hunting societies observed a variety of rituals in their hunting practices in order to return the soul of the animal to its supernatural “owner.” Failure to observe these rituals was a transgression that threatened to unbalance the cosmological order and impact the success of future hunts. This failure could only be resolved through further specific rituals (Smith, 1982). In this example, sociologists would note that the taboo acts as a form of ritualized social control that encourages people to act in ways that benefit the wider society, such as the prevention of overhunting.

A third common dimension of various religions is the promise of access to some form of unique spiritual experience or feeling of immediate connection with a higher power. The pursuit of these indescribable experiences explains one set of motives behind the continued prevalence of religion in Canada and around the world. From this point of view, religion is not so much about thinking a certain way (i.e., a formal belief system) as about feeling a certain way. These experiences can come in several forms: the incredible visions or revelations of the religious founders or prophets (e.g., the experiences of the Buddha, Jesus, or Muhammed), the act of communicating with spirits through the altered states of consciousness used by tribal shamen, or the unique experiences of expanded consciousness accessed by individuals through prayer or meditation.

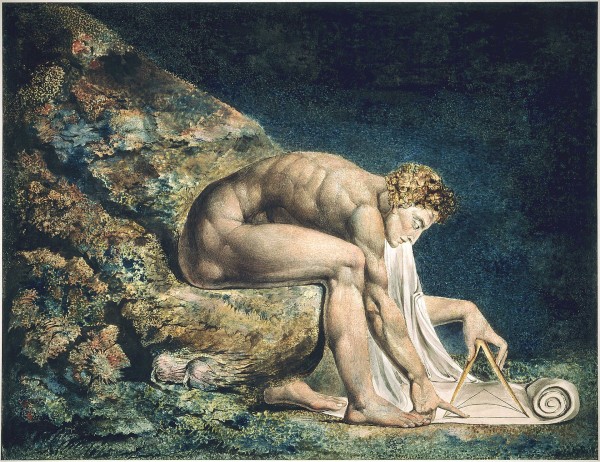

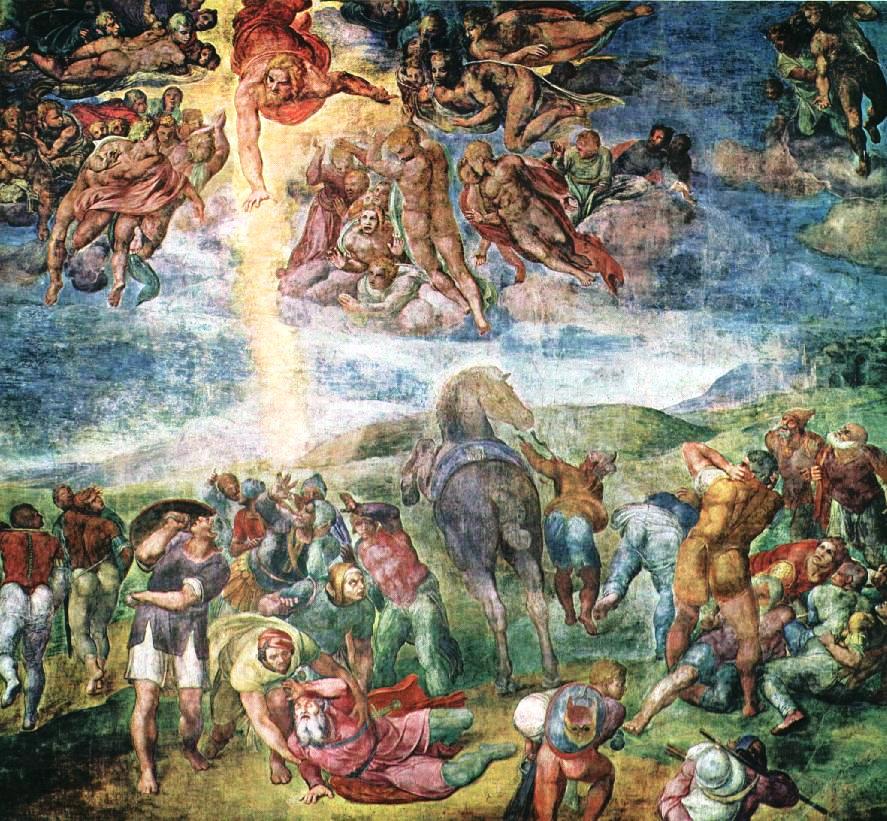

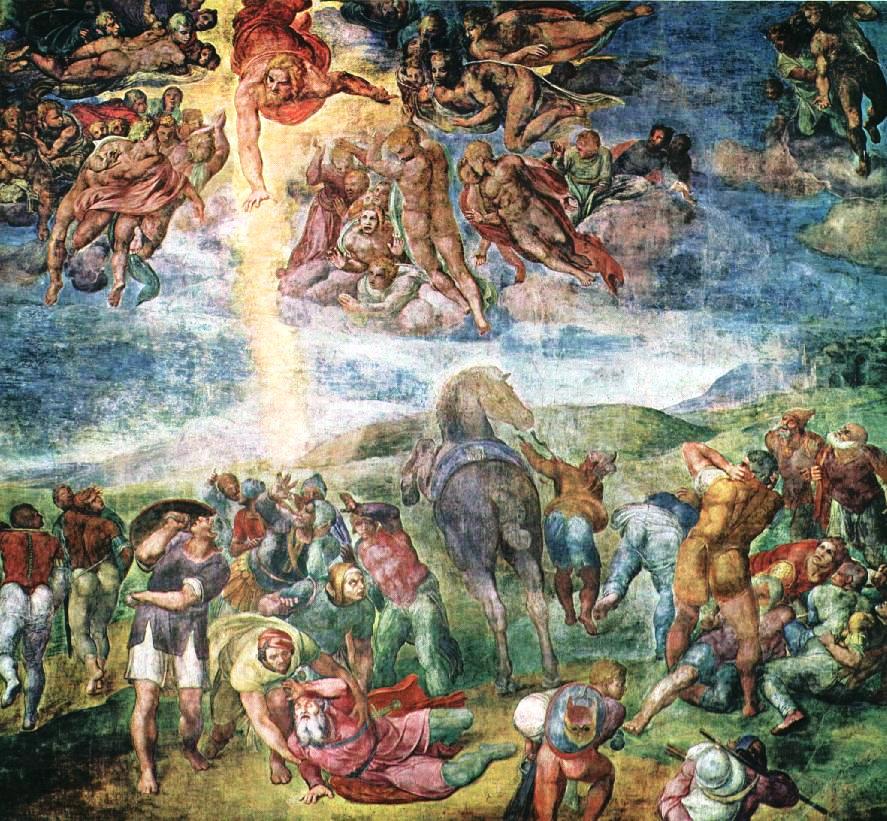

Figure 15.6. Michelangelo’s “Conversion of Saul” (1542) depicts the overpowering nature of the transformative experience, or mysterium tremendum, that lies at the core of religion. [Long Description] (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

While being exposed to a higher power can be awe inspiring, it can also be intensely overwhelming for those experiencing it. These experiences reveal a form of knowledge that is instantly transformative. The historical example of Saul of Tarsus (later renamed St. Paul the Apostle) in the Christian New Testament is an example. Saul was a Pharisee heavily involved in the persecution of Christians. While on the road to Damascus Jesus appeared to him in a life-changing vision.

And as he journeyed, he came near Damascus: and suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven:

And he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying unto him, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?

And he said, Who art thou, Lord? And the Lord said, I am Jesus whom thou persecutest: it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks.

And he trembling and astonished said, Lord, what wilt thou have me to do? And the Lord said unto him, Arise, and go into the city, and it shall be told thee what thou must do.

And the men which journeyed with him stood speechless, hearing a voice, but seeing no man.

And Saul arose from the earth; and when his eyes were opened, he saw no man: but they led him by the hand, and brought him into Damascus.

And he was three days without sight, and neither did eat nor drink (Acts 9:1-22).

The experience of divine revelation overwhelmed Saul, blinded him for three days, and prompted his immediate conversion to Christianity. As a result he lived out his life spreading Christianity through the Roman Empire.

While specific religious experiences of transformation like Saul’s are often the source or goal of religious practice, established religions vary in how they relate to them. Are these types of experiences open to all members or just those spiritual elites like prophets, shamen, saints, monks, or nuns who hold a certain status? Are practitioners encouraged to seek these experiences or are the experiences suppressed? Is it a specific cultivated experience that is sought through disciplined practice, as in Zen Buddhism, or a more spontaneous experience of divine inspiration, like the experience of speaking in tongues in Evangelical congregations? Do they occur quite often or are they more rare/singular? Each religion has their own answers to these questions.

Finally, the forth common dimension of religion is the formation of specific forms of social organization or community. Durkheim (1915/1964) emphasized that religious beliefs and practices “unite in one single community called a Church, all those who adhere to them,” arguing that one of the key social functions of religion is to bring people together in a unified moral community. Dawson and Thiessen (2014) elaborate on this social dimension shared by all religions. First, the beliefs of a religion gain their credibility through being shared and agreed upon by a group. It is easier to believe if others around you (who you respect) believe as well. Second, religion provides an authority that deals specifically with social or moral issues such as determining the best way to live life. It provides a basis for ethics and proper behaviours, which establish the normative basis of the community. Even as many Canadians move away from traditional forms of religion, many still draw their values and ideals from some form of shared beliefs that are religious in origin (e.g., “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”). Third, religion also helps to shape different aspects of social life, by acting as a form of social control, and supporting the formation of self-control, that is vital to many aspects of a functional society. Fourth, although it may be on the decline in Canada, places of religious worship function as social hubs within communities, providing a source of entertainment, socialization, and support.

By looking at religions in terms of these four dimensions — belief, ritual, experience, and community — sociologists can identify the important characteristics they share while taking into consideration and allowing for the great diversity of the world religions.

Table 15.2. The Religions of the World. | World Religion | Origins | Beliefs | Rituals and Practices |

|---|

Judaism

Symbol: The star of David | Judaism began in ancient Israel about 4,000 years ago. The prophet Abraham was the first to declare that there was to be only one true God. Moses, centuries later, then led the Jewish people away from slavery in Egypt, which was a defining moment for Judaism. Moses is credited with writing the Torah, the sacred Jewish texts, which consists of the five books of Moses. | Followers of Judaism are monotheistic, believing that there is only one true God. Israel is the sacred land of the Jewish people, and it is seen as gift to them — the children of Israel — from God. According to the Torah, Jewish believers must live a life of obedience to God because life itself is a gift granted by God to his disciples (Sanders, 2009). Followers of Judaism live in accordance to the ten commandments revealed to Moses by God on Mount Sinai. These commandments outline the instructions for how to live life according to God. | Judaism has many rituals and practices that followers of the faith carry out. Jewish people have strict dietary laws that originate in the Torah, called Kosher laws. The goal of these laws is not a concern for health, but for holiness. Examples of foods that are prohibited include, pig, hare, camel, and ostrich meat, and crustacean and molluscan seafood. Additionally, certain food groups are banned from being consumed when combined, for example, meat and dairy together (Tieman & Hassan, 2015).

Other examples of Jewish rituals are the practices of circumcision and Bar and Bat Mitzvahs. These rites of passage for young boys (bar) and young girls (bat) mark the transition into manhood and womanhood. During these celebrations, the coming of age process is celebrated.

Jewish followers also carry out multiple prayers each day, reaffirming and demonstrating their reciprocal love with God. |

Christianity

Symbol: The Cross | Christianity began in approximately 35 CE — i.e., the date of the crucifixion — in the area of the Middle East that is now known as Israel. Christianity began with recognition of the divinity of Jesus of Nazareth (Dunn, 2003). A poor Jewish man, Jesus was unsatisfied with Judaism and took it upon himself to seek a stronger connection to the word of God defined by the prophets. Thus, Christianity initially developed as a sect of Judaism. It developed into a distinct religion as Jesus developed a stronger following of those who believed that he was the son of God. The crucifixion of Jesus was the first of many tests of faith of Christians (Guy, 2004).

A division emerged within Christianity between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism with the division of the Roman Empire into East and West. A second division occurred during the Protestant Reformation when Protestant sects emerged to challenge the authority of the Catholic church and Papacy to be intermediaries between God and Christian believers. | At the core, to be Christian is to believe in the trinity of father, son, and holy spirit as one God: the God of love. Out of love for humanity, God allowed his only son to be sacrificed in the crucifixion to expiate their sins. Christians are admonished to love God, and to love their neighbours and enemies “as themselves.” They believe in God’s love for all things, have faith that God is watching over them at all times and that Jesus, the son of God, will return when the world is ready. Jesus is the exemplar of the religion, demonstrating the way in which to be a proper Christian. In the Christian faith, the theodicy, or the way that Christianity explains why God allows bad things happen to good people, is shown through faith in Jesus. If believers follow in Jesus’ footsteps, they will have access to heaven. Unfortunate occurrences are acts of God that test the faith of his followers. Therefore, by maintaining faith in God’s love, Christians are able to carry on with their lives when confronted with tragedy, injustice and suffering | There are many rituals and practices that are central to Christianity, known as the sacraments. For example, the sacrament of baptism involves the literal washing of the person with water to represent the cleansing of their sins. Today, the ritual of baptism has become less common, however, historically the process of baptism was considered an integral rite in order to christen the individual and to wipe away their ancestral or original sin (Hanegraaff, 2009). Other sacraments include the Eucharist (or communion), confirmation, penance, anointing the sick, marriage, and Holy Orders (or ordination). However, not all sects of Christianity follow these.

One of the core qualities and practices of Christianity is caring for the poor and disadvantaged. Jesus, a poor man himself, fed and nurtured the poor, demonstrating care for all, and is thus seen to be the exemplar of morality (Dunn, 2003). Christian churches are often institutions that demonstrate how to follow Jesus, running charities and food banks, and housing the homeless and the sick. |

Islam

Symbol: Crescent and the Star | Originating in Saudi Arabia, Islam is a monotheistic religion that developed in approximately 600 CE. During this time, the society of Mecca was in turmoil. Muhammad, God’s messenger, received the verses of the Quran directly from the Angel Gabriel during a period of isolated prayer on Mt. Hira. He developed a following of people who eventually united Arabia into a single state and faith through military struggle against polytheistic pagans. Followers of the Islamic faith are referred to as Muslims.

Today, a division exists with Islam originating from disagreement regarding Muhammad’s legitimate successor. These two groups are known as Sunni’s and Shia’s, the former making up the majority of Muslims. | Central to Islam is the belief that the God, Allah, is the only true God and that Muhammad is God’s Messenger, otherwise known as the Prophet. God also demands that Muslims be fearful and subservient to him as He is the master, and the maker of law (Ushama, 2014).

In Islamic faith, the Quran is the sacred text that Muslims believe is the direct word of God, dictated by the Angel Gabriel to Muhammad (Ushama, 2014). | Islam outlines five pillars that must be upheld by Islamic followers if they are to be true Muslims.

1) Daily recitation of the creed (Shahadah) which states that there is only one God and Muhammad is God’s messenger;

2) Prayer five times daily;

3) Providing financial aid to support poor Muslims and to promote the practice of Islam;

4) Participation in the month long fast during the 9th month of the Islamic calendar;

5) Completion of a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their life (“Pillars of Islam,” 2008). |

Hinduism

Symbol: Om or Aum | Hinduism originated in India and Nepal, however the exact origin of this widespread religion is highly contested. There is no known founder, differing strongly from the other religions discussed here, which have strong origin stories of the individuals that first posited the specific way of religious life (Flood, 1996). | The beliefs characteristic of Hinduism are a belief in reincarnation, and a belief that all actions have direct effects, referred to as Karma (Flood, 1996). In contrast with other world religions, Hinduism is not as strongly defined by what followers believe in but instead by what they do. The Dharma is what outlines a Hindu’s duty in life, identifying individuals with a place within the dharmic social stratification system, or the caste system. This classification greatly dictates what a Hindu can and cannot do. Hindu followers believe in one God that is represented by a multitude of sacred forms known as deities (Flood, 1996). In Hindu religion, in death, only the body dies while the soul lives on. Individuals are reincarnated, surviving death to be reborn in a new form. This new form is believed to be dependent on the way in which the individual lived their life, with the proper way being identified as their acting in accordance to the duties of their caste position (Flood, 1996). | In the religion of Hinduism, practice is more important than belief. One ritualistic practice that is carried out by Hindu followers is the act of making offerings of incense to the deities. This act of offering is seen as a “mediation” to open to the lines of communication between the sacred and the profane, or the deity and the individual. This correspondence is of great significance to Hindu followers (Flood, 1996).

Another widespread ritual practice is yoga, which is a practice of holding postures while focusing on one’s breath. Yoga is used to silence the mind, allowing it to reflect the divine world. This practice brings the believer closer to unification with the divine. |

Buddhism

Symbol: The Dharma Wheel (the eight spokes of this wheel represent the eightfold path). | Buddhism refers to the teachings of Guatama Buddha. It originated in India in approximately 600 BCE. Buddha, originally a follower of the Hindu faith, experienced enlightenment, or Bohdi, while sitting under a tree. It was in this moment that Buddha was awakened to the truth of the world, known as the Dharma. Buddha, an ordinary man, taught his followers how to follow the path to Enlightenment. Thus Buddhism does not believe in a divine realm or God as a supernatural being, but instead follows the wisdom of the founder (Rinpoche, 2001). | Buddhists are guided through life by the Dharma or four noble truths.

1) The truth that life is impermanent and therefore generates suffering such as sickness or misfortune;

2) The truth that the origin of suffering is due to the existence of desire or craving;

3) The truth that there is a way to bring this suffering to a halt and achieve release from the cycle of suffering and rebirth;

4) The truth of following the eight-fold path as a way to end this suffering (Tsering, 2005).

This path consists of the ‘right’ view to carry out one’s life. Buddhists believe in reincarnation, and that one will continue to be reborn, requiring them to continue the study of and dedication to the four noble truths and the eightfold path until Enlightenment is achieved. Only then will the cycle stop. Therefore, the end to suffering is only reached through the cessation of the craving or desire that drives the cycle of rebirth (Tsering, 2005). | The noble eight-fold path includes eight prescriptions: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. These outline the “middle path” between the extremes of sensualism and acseticism, which gives rise to true knowledge, peace, and Enlightenment (Tsersing, 2005).

A key ritual practice of Buddhism is meditation. This practice is used by followers to learn detachment from desire and gain insight into the inner workings of their mind in order to come to greater understandings of the truth of the world. In the Buddha’s example, meditation on breath or on chanted mantras, which are often key passages of the Buddha’s sutras (teachings), is a key practice to reach the place of Enlightenment or awakening. |

Making Connection: Social Policy and Debate

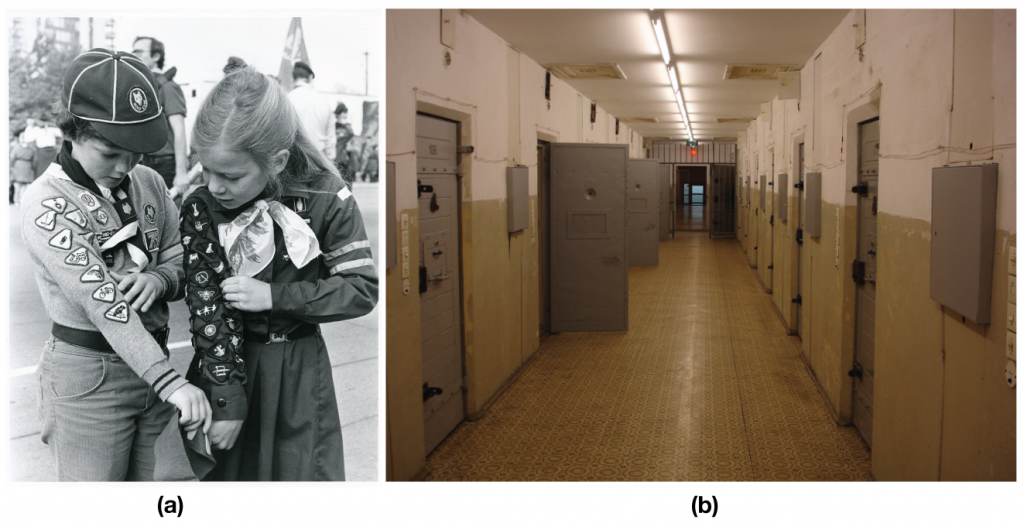

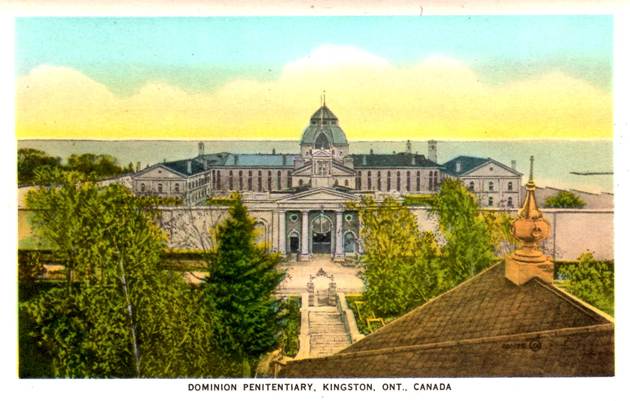

Residential Schools and the Church

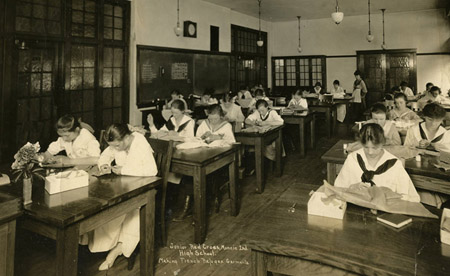

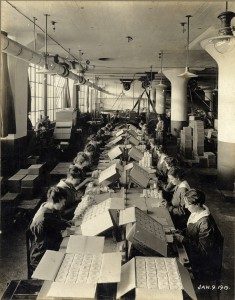

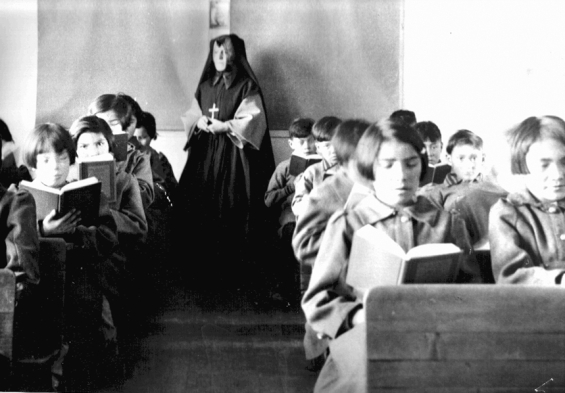

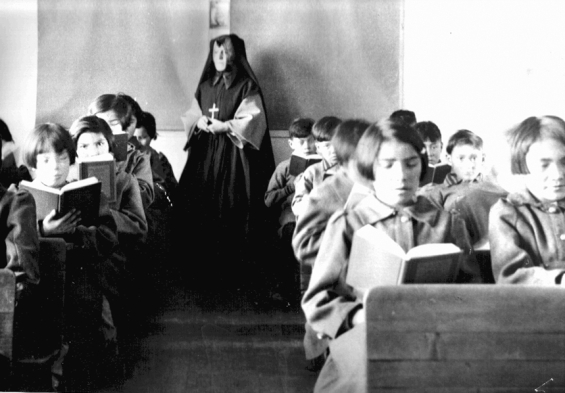

Figure 15.7. Students from Fort Albany Residential School, Ontario, reading in class overseen by a nun, circa 1945. (Image courtesy of Edmund Metatawabin collection at the University of Algoma/Wikipedia)

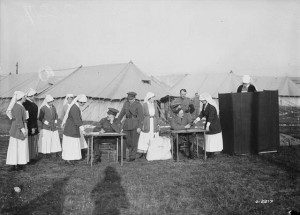

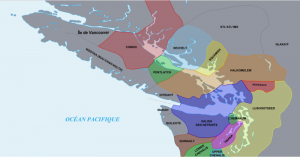

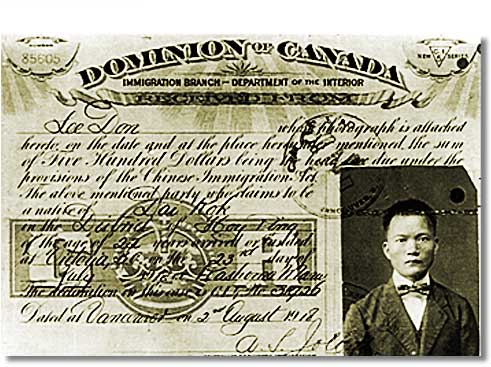

Residential schools were a key institution responsible for the undermining of Aboriginal culture in Canada. Residential schools were run by the Canadian government alongside the Anglican, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, and United Churches (Blackburn, 2012). These schools were created with the purpose of assimilating Aboriginal children into North American culture (Woods, 2013).

In 1920 the government legally mandated that all Aboriginal children between the ages of seven and fifteen attend these schools (Blackburn, 2012). They took the children away from their families and communities to remove them from all influence of their Aboriginal identities that could inhibit their assimilation. Many families did not want their children to be taken away and would hide them, until it became illegal (Neeganagwedgin, 2014). Under the Indian Act, they were also not allowed lawyers to fight government action, which added greatly to the systemic marginalization of these people. The churches were responsible for daily religious teachings and daily activities, and the government was in charge of the curriculum, funding, and monitoring the schools (Blackburn, 2012).

There were as many as 80 residential schools in Canada by 1931 (Woods, 2013). It was known early on in this system that there were flaws, but they still persisted until the last residential school was abolished in 1996. As we now know, the experience of residential schools for Aboriginal children was traumatic and dreadful. Within the walls of these schools, children were exposed to sexual and physical abuse, malnourishment, and disease. They were not provided with adequate clothing or medical care, and the buildings themselves were unsanitary and poorly built.

The Roman Catholic Church created the most residential schools, with the Anglican Church second (Woods, 2013). There has been much debate surrounding the Church’s involvement in these atrocious organizations. Former Primate and Archbishop Michael Peers apologized in 1993 for the Anglican Church’s part in the residential schools. Canada’s first Aboriginal Anglican Bishop Gordon Beardy forgave the Anglican Church in 2001.

By 2001, there were more than 8,500 lawsuits against the Churches and Canadian government for their role in the residential schools (Woods, 2013). Because of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, former students of the residential schools are now eligible for $10,000, on top of $3,000 for each year they attended the schools. A lawsuit filed by former students of the Alberni Indian Residential School was one of the first to get to the Supreme Court of Canada, and the first to deem both the government and church equally responsible.

Apologies are still being made on behalf of the churches involved in the residential schools, but the effects it has had on the Indigenous peoples and their culture are perpetuating today. The Christian churches and mission groups have done good things for societies, but their role in these residential schools was immoral and unjust to the Aboriginal people.

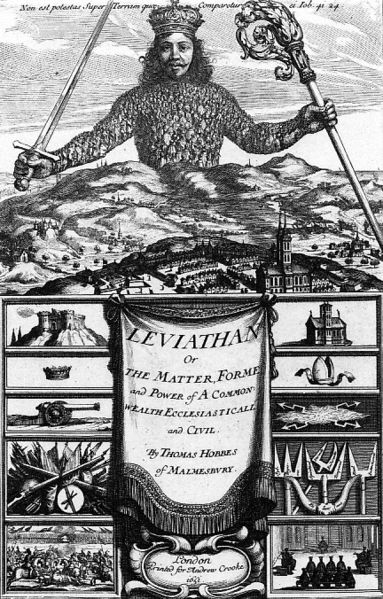

Types of Religious Organization

In every society there are different organizational forms that develop for the practice of religion. Sociologists are interested in understanding how these different types of organization affect spiritual beliefs and practices. They can be categorized according to their size and influence into churches (ecclesia or denomination), sects, and cults. This allows sociologists to examine the different types of relationships religious organization has with the dominant religions in their societies and with society itself.

A church is a large, bureaucratically organized religious organization that is closely integrated into the larger society. Two types of church organizations exist. The first is the ecclesia, a church that has formal ties with the state. Like the Anglican Church of England, an ecclesia has most or all of a state’s citizens as its members. As such, the ecclesia forms the national or state religion. People ordinarily do not join an ecclesia, instead they automatically become members when they are born. Several ecclesiae exist in the world today, including Salifi Islam in Saudi Arabia, the Catholic Church in Spain, the Lutheran Church in Sweden, and, as noted above, the Anglican Church in England.

In an ecclesiastic society there may be little separation of church and state, because the ecclesia and the state are so intertwined. Many modern states deduct tithes automatically from citizen’s salaries on behalf of the state church. In some ecclesiastic societies, such as those in the Middle East, religious leaders rule the state as theocracies — systems of government in which ecclesiastical authorities rule on behalf of a divine authority — while in others, such as Sweden and England, they have little or no direct influence. In general, the close ties that ecclesiae have to the state help ensure they will support state policies and practices. For this reason, ecclesiae often help the state solidify its control over the populace.

The second type of church organization is the denomination, a religious organization that is closely integrated into the larger society but is not a formal part of the state. In modern religiously pluralistic nations, several denominations coexist. In Canada, for example, the United Church, Catholic Church, Anglican Church, Presbyterian Church, Christian and Missionary Alliance, and the Seventh-day Adventists are all Christian denominations. None of these denominations claim to be Canada’s national or official church, but exist instead under the formal and informal historical conditions of separation between church and state.

So historically, in Canada, denominationalism developed formally (as a result of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, which granted Roman Catholics the freedom to practice their religion) and informally (as a result of the immigration of people with different faiths during the expansion of settlement of Canada in the 19th and early 20th centuries). Under the model of denominationalism, many different religious organizations compete for people’s allegiances, creating a kind of marketplace for religion. In the United States, this is a formal outcome of the Constitutional 1st Amendment protections (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”). In Canada, “freedom of religion” was not constitutionally protected until the introduction of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982.

Figure 15.8. A 62-foot-tall Jesus sculpture — “King Of Kings” — at the Solid Rock megachurch north of Cincinnati, Ohio. (Photo courtesy of Joe Shlabotnik/Wikimedia Commons)

A relatively recent development in religious denominationalism is the rise of the so-called megachurch in the United States, a church at which more than 2,000 people worship every weekend on the average (Priest, Wilson, & Johnson, 2010; Warf & Winsberg, 2010). These are both denominational and non-denominational, (meaning not officially aligned with any specific established religious denomination). About one-third are nondenominational, and one-fifth are Southern Baptist, with the remainder primarily of other Protestant denominations. Several dozen have at least 10,000 worshippers and the largest U.S. mega church, in Houston, has more than 35,000 worshippers, nicknamed a “gigachurch.” There are more than 1,300 mega churches in the United States — a steep increase from the 50 that existed in 1970 — and their total membership exceeds 4 million.

Compared to traditional, smaller churches, mega churches are more concerned with meeting their members’ non-spiritual, practical needs in addition to helping them achieve religious fulfillment. They provide a “one-stop shopping” model of religion. Some even conduct market surveys to determine these needs and how best to address them. As might be expected, their buildings are huge by any standard, and they often feature bookstores, food courts, and sports and recreation facilities. They also provide day care, psychological counseling, and youth outreach programs. Their services often feature electronic music and light shows. Despite their popularity, they have been criticized for being so big that members are unable to develop close bonds with each other and with members of the clergy that are characteristic of smaller houses of worship. On the other hand, supporters say that mega churches bring many people into religious worship who would otherwise not be involved.

A sect is a small religious body that forms after a group breaks away from a larger religious group, like a church or denomination. Dissidents believe that the parent organization does not practice or believe in the true religion as it was originally conceived (Stark & Bainbridge, 1985). Sects are relatively small religious organizations that are not closely integrated into the larger society. They often conflict with at least some of its norms and values. The Hutterites are perhaps the most well-known example of a contemporary sect in Canada; an Anabaptist group — literally “one who baptizes again” — that broke away from mainstream Christianity in the 16th century. Their migration from Tyrol, Austria, due to persecution eventually lead to their immigration to the Dakotas in the 19th century and then to the Canadian prairies, as conscientious objectors following WWI.

Figure 15.9. A Hutterite girl holding her baby sister in Southern Alberta, 1950s. (Image courtesy of Galt Museum & Archives/Wikimedia Commons)

Typically, a sect breaks away from a larger denomination in an effort to restore what members of the sect regard as the original views of the religion. Because sects are relatively small, they usually lack the bureaucracy of denominations and ecclesiae, and often also lack clergy who have received official training. Their worship services can be intensely emotional experiences, often more so than those typical of many denominations, where worship tends to be more formal and restrained. Members of many sects typically proselytize and try to recruit new members into the sect. If a sect succeeds in attracting many new members, it gradually grows, becomes more bureaucratic, and, ironically, eventually evolves into a denomination. Many of today’s Protestant denominations began as sects, as did the Hutterites, Mennonites, Quakers, Doukhobors, Mormons, and other groups.

A cult or New Religious Movement is a small religious organization that is at great odds with the norms and values of the larger society. Cults are similar to sects but differ in at least three respects. First, they generally have not broken away from a larger denomination and instead originate outside the mainstream religious tradition. Second, they are often secretive and do not proselytize as much. Third, they are at least somewhat more likely than sects to rely on charismatic leadership based on the extraordinary personal qualities of the cult’s leader.

Although the term “cult” raises negative images of crazy, violent, small groups of people, it is important to keep in mind that major world religions, including Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, and denominations such as the Mormons all began as cults. Cults, more than other religious organizations, have been subject to contemporary moral panics about brainwashing, sexual deviance, and strange esoteric beliefs. However, research challenges several popular beliefs about cults, including the ideas that they brainwash people into joining them and that their members are mentally ill. In a study of the Unification Church (Moonies), Eileen Barker (1984) found no more signs of mental illness among people who joined the Moonies than in those who did not. She also found no evidence that people who joined the Moonies had been brainwashed into doing so.

Another source of moral panic about cults is that they are violent. In fact, most are not violent. Nevertheless, some cults have committed violence in the recent past. In 1995 the Aim Shinrikyo (Supreme Truth) cult in Japan killed 10 people and injured thousands more when it released bombs of deadly nerve gas in several Tokyo subway lines (Strasser & Post, 1995). Two years earlier, the Branch Davidian cult engaged in an armed standoff with federal agents in Waco, Texas. When the agents attacked its compound, a fire broke out and killed 80 members of the cult, including 19 children; the origin of the fire remains unknown (Tabor & Gallagher, 1995).

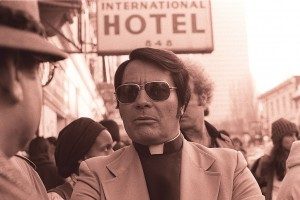

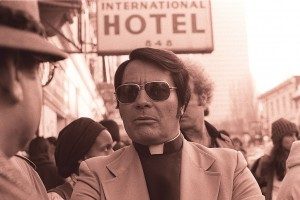

Figure 15.10. The Reverend Jim Jones of the People’s Temple: “We didn’t commit suicide; we committed an act of revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world.” (Image courtesy of Nancy Wong/Wikimedia Commons)

A few cults have also committed mass suicide. More than three dozen members of the Heaven’s Gate cult killed themselves in California, in March 1997, in an effort to communicate with aliens from outer space (Hoffman & Burke, 1997). Some two decades earlier, in 1978, more than 900 members of the People’s Temple cult killed themselves in Guyana under orders from the cult’s leader, the Reverend Jim Jones (Stoen, 1997). Similarly, in Canada, on the morning of October 4th, 1994, a blaze engulfed a complex of luxury condominiums in the resort town of Morin-Heights, Quebec. Firefighters found the bodies of a Swiss couple, Gerry and Collette Genoud, in its ruins. At first it was thought that the fire was accidental, but then news arrived from Switzerland of another odd set of fires at homes owed by the same men who owned the Quebec condominiums. All the fires had been set with improvised incendiary devices, which made the police realize they were dealing with a rare incidence of mass murder suicide involving members of an esoteric religious group known as the Solar Temple. From the recorded and written messages left behind by the group, it is clear that the leaders felt it was time to effect what they called a transit to another reality associated with Sirius.

It is important to note that cults or new religious movements are very diverse. They offer spiritual options for people seeking purpose in the modern context of state secularism and religious pluralism. Being intense about one’s religious views often breaks the social norms of largely secular societies, leading to misunderstandings and suspicions. Members of new religions run the risk of being stigmatized and even prosecuted (Dawson, 2007). Modern societies highly value freedom and individual choice, but not when exercised in a manner that defies expectations of what is normal.

Making Connections: Case Study

Brother XII and the Aquarian Foundation

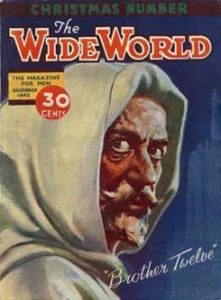

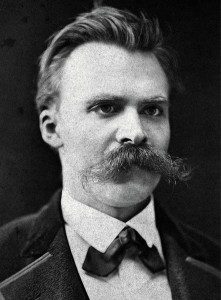

Figure 15.11. Brother Twelve, the “devil from De Courcy Island.” (Image in the public domain)

Born as Edward Arthur Wilson, the man known as Brother XII travelled the world as a sailor studying various religions. Even at a young age he claimed to be in touch with supernatural beings (Gorman, 2012). In 1927, having taken the name of Brother XII, Wilson established the Aquarian Foundation at Cedar-by-the-Sea, just south of Nanaimo on Vancouver Island, which expanded to include colonies on nearby De Courcy and Valdez Islands. At its height it had over 2000 followers around the world, many of whom sent over large sums of money.

The Aquarian Foundation was based on the teachings on the Theosophical Society, which was an organization formed in New York City in 1875. Theosophy had much in common with the beliefs of Buddhism and Hinduism, such as the belief in reincarnation. It was radically different than the dominant Christian belief of the time. Instead of a separation of the spiritual world and the natural world, spirit and nature were considered to be intertwined in people’s daily lives as one universal life force. Theosophy also promoted the idea that there was a spiritual world beyond death inhabited by evolved spiritual beings, whose wisdom could be accessed through the occult reading of esoteric signs and the intervention of spiritual mediums (Scott, 1997).

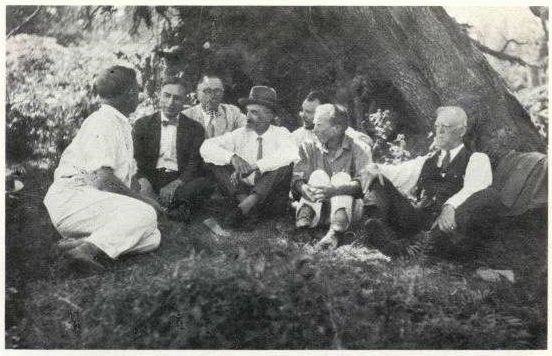

Figure 15.12. Brother Twelve (with hat) at the center of a group of followers. “I am not a person filled with power, but a power using a personality,” he stated in a circular letter (cited in McKelvie, 1966). (Image from McKelvie, 1966)

At the time Brother XII ‘s ambitions seemed reasonable enough and many felt the foundation itself represented the promise of great spiritual renewal for an increasingly materialistic society. Brother XII had his followers build homes and cabins at the foundation’s headquarters at Cedar-by-the-Sea and on De Courcy Island. These isolated areas provided a place to get away from the social pressures of the outside world. However, an insurrection took place when Brother XII announced to his followers that he was the reincarnation of the Egyptian God Osiris. Between 1928 and 1933, a series of trials involving Brother XII occurred, which included allegations of misusing foundation funds and having extramarital affairs. News reports claimed that he used black magic to cause witnesses and several members of the audience to faint (Rutten, 2009).

In 1929, as rumours about Wilson’s behaviour spread, the B.C. provincial cabinet dissolved the foundation. Those who remained were subjected to Wilson’s paranoia and became increasingly isolated from the outside world. Wilson himself became increasingly authoritarian and used social pressure to convince members into performing gruelling physical labour that was virtually on the same level as slavery. He did this by telling them these activities were tests of fitness to advance their spirituality. In 1931, the group was finally dissolved and Wilson disappeared from the Nanaimo area along with hundreds of thousands of dollars of Foundation money and Mabel Skottowe (one of the women with whom he was accused of having an extramarital affair). They reportedly left by tugboat and eventually made their way to Switzerland. The majority of reports say that he died in Switzerland in 1934, though some that say he was seen in San Francisco with his lawyer after his alleged death.

The story of Brother XII illustrates many themes from the sociology of New Religious Movements and cults. According to Cowan (2015), because most people have little direct knowledge of cults and mainly get their information through sensationalist media reports, cults are easily presented as targets of moral panic for being immoral, extreme or dangerous. The three main accusations that cults face are that they engage in brainwashing, acts of sexual deviance and social isolationism. Each of these accusations applied to the media reports on the Aquarian Foundation although their dominant theme centered on the claim that Brother XII was a fraud.

15.2. Sociological Explanations of Religion

While some people think of religion as something individual (because religious beliefs can be highly personal), for sociologists religion is also a social institution. Social scientists recognize that religion exists as an organized and integrated set of beliefs, behaviours, and norms centred on basic social needs and values. Moreover, religion is a cultural universal found in all social groups. For instance, in every culture, funeral rites are practiced in some way, although these customs vary between cultures and within religious affiliations. Despite differences, there are common elements in a ceremony marking a person’s death, such as announcement of the death, care of the deceased, disposition, and ceremony or ritual. These universals, and the differences in how societies and individuals experience religion, provide rich material for sociological study. But why does religion exist in the first place?

Evolutionary Psychology

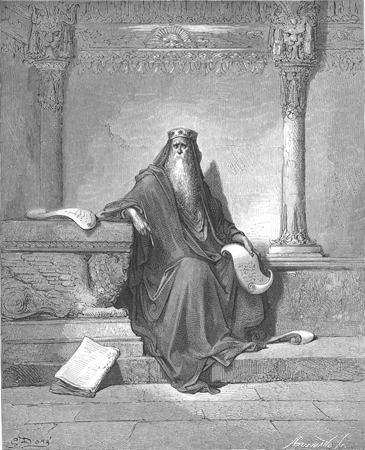

“Blind Pharisee, cleanse first that [which is] within the cup and platter, that the outside of them may be clean also” (Matthew 23:26, King James Bible);

“Let the (husband) employ his (wife)…in keeping clean, in religious duties, in the preparation of his food, and in looking after the household utensils” (9:11, Hindu Laws Of Manu).

Despite the conflict that has accompanied religion over the centuries, it still continues to exist, and in some cases thrive. How do we explain the origins and continued existence of religion? We will examine sociological theories below, but first we turn to evolutionary and psychological explanations.

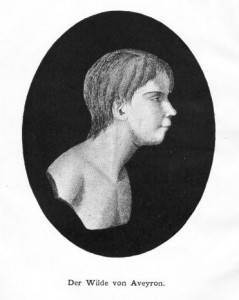

Many psychologists explain the rise and persistence of religion in terms of Darwinian evolutionary theory. For this argument, they provide a psychological definition of the core religious experience or state of being common to all religion’s diverse social forms and settings. Psychologist Roger Cloninger (1993) defines this core religious experience as the disposition towards self-transcendence. It has three measurable components: self-forgetfulness (absorption in tasks and the ability to lose oneself in concentration), transpersonal identification (perception of spiritual union with the cosmos and the ability to reduce boundaries of self vs. other), and mysticism (perception or acceptance of things that cannot be rationally explained ). The argument is that because this is a universal phenomenon, it must have a common physiological or genetic basis that is passed on between generations that enhances human survival.

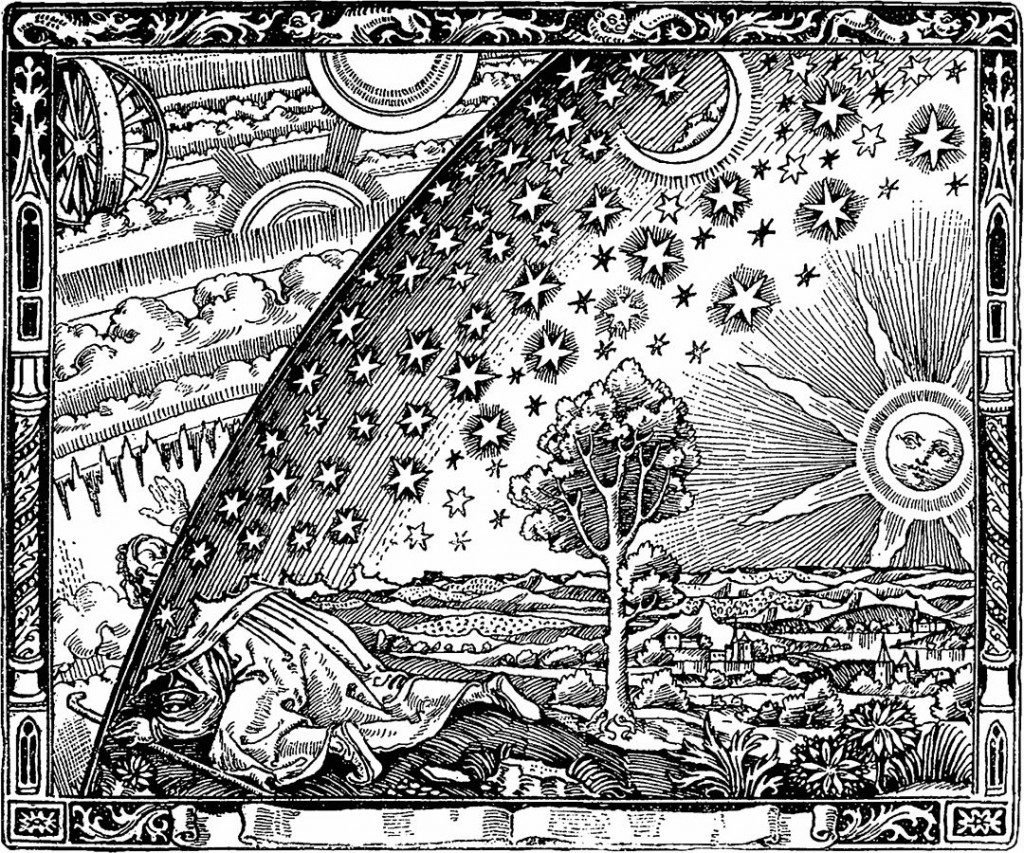

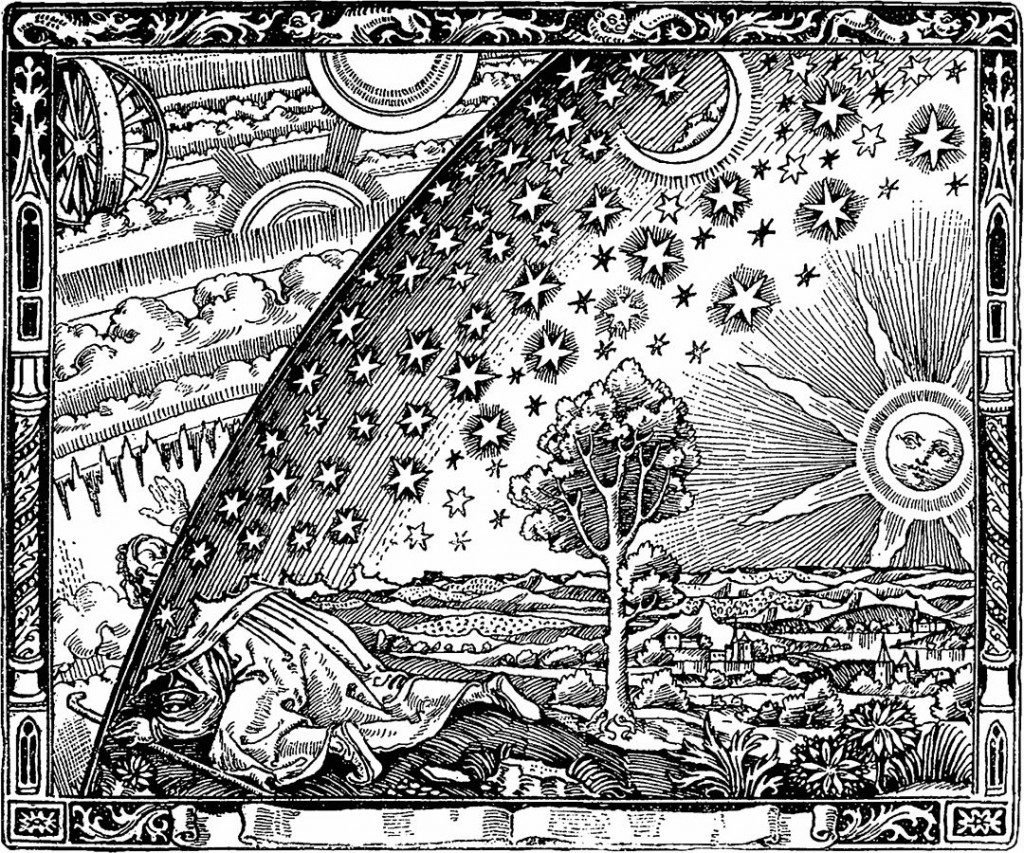

Figure 15.13. “The place where heaven and earth meet.” Psychologists approach religion as a product of the individual capacity for experiences of self-transcendence. Is this capacity wired into our genes? (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

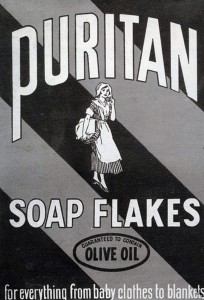

According to Charles Darwin all species are involved in a constant battle for survival, using adaptions as their primary weapon against an ever-changing, and hostile environment. Adaptions are genetic, or behavioral traits that are shaped by environmental pressures, and genetic variation. By dissecting religion to a core set of purposes, it can be categorized as an adaption that increases the chances of human survival. All adaptions successfully passed on to future generations aided at one point either in reproduction or survival because the genes that selected for them were passed on. This is the rule of natural selection (Darwin, 1859).

Much of evolutionary psychology aims at explaining the possible environments in which certain adaptions were selected. Although religion has the potential to cause unwanted side effects, such as wars, it still provides much greater benefits, by responding to numerous survival problems through collective religious processes. A very specific benefit, for example, is disease prevention. Many historic religions placed an emphasis on cleanliness, comparing it to spiritual purity. Consequently there is also an evolutionary benefit to this religious virtue. During a time period where disease was a constant threat to survival, idealizing cleanliness helped minimize communicable diseases from food, animals, and even humans.

Although disease prevention has been an important byproduct of religious practices around the world, evolutionary psychologists argue that the main benefit religion has provided to human survival is the mutual support provided by fellow members. More specifically, religion creates a framework for social cohesion and solidarity, even during times of loss, and grief, which has been a crucial competitive strategy of the human species. Rather than each individual being exclusively concerned with their own survival — in a kind of “survival of the fittest” logic — the religious disposition to self-transcendence provides a mechanism that explains the altruistic core of religious practice and the capacity of individuals to sacrifice themselves for the group or for abstract beliefs.

Dean Hamer (2005) for example describes a specific gene that correlates with the capacity for self-transcendence. After his research team isolated an association between the VMAT2 gene sequence and populations who scored high on psychological scales for self-transcendence, Hamer noted these genes were connected to the production of neurotransmitters known as monoamines. The effects of monoamines on the meso-limbic systems in the human body were similar to many stimulant drugs: feelings of euphoria and positive well-being. Moreover, his findings suggested that 40-50% of self-transcendence was heritable. What is striking about this evidence is the implication that evolution has favoured genes that are often displayed in religious populations. Hamer extends the evolutionary argument to suggest that religion, grounded genetically in a neuro-chemical capacity for self-transcendence, provides competitive advantages for the human species in the forms of community well-being (higher rates of reciprocity and social welfare) and longevity (reduction of maladaptive behaviours and increased cleanliness).

Many similar effects can be observed in the present environment. Strawbridge, Sherna, Cohen, and Kaplan, (2001) conducted a 30-year longitudinal study on religious attendance and survival. Although they found that weekly religious attendance more often assisted in targeting and reducing maladaptive behaviors such as smoking, it also aided in maintaining social relations, and marriage (Strawbridge et al., 2001). Similar studies show correlations between religious affiliation to Christianity, and the self-perceived happiness of German students (Francis, Robbins, & White, 2003). Evolutionary psychology argues that these modern tendencies to feel happiness during a church congregation to reduce maladaptive behaviours are innate, sculpted by centuries of exposure to religion.

Evolutionist Richard Dawkins hypothesized a similar reason why religion has created such a lasting impact on society. His theory is explained by the creation of ‘memes’. Comparable to genes, memes are bits of information that can be imitated and transferred across cultures and generations (Dawkins, 2006). Unlike genes, which are physically contained within the human genome, memes are the units or “genetic material” of culture. As a vocal proponent of atheism, Dawkins believes the idea of God is a meme, working in the human mind the same way as a placebo effect. The God meme contains tangible benefits to human society such as answers to questions about human transcendence and superficial comfort for daily difficulties, but the idea of God itself is a product of the human imagination (Dawkins, 2006). Although a human creation, the God meme is incredibly appealing, and as a result, has continually been passed on through cultural transfusion.

The logic of evolutionary psychology suggests that it is possible for religion to be replaced by another mechanism that is more beneficial to human survival. Just as Dawkins hypothesized that religious memes colonized societies around the world, this process could also be applied to secular memes. Modern secular countries provide public institutions that create the same social functions as religion, without the disadvantages of “irrational” religious restrictions based on unverifiable beliefs. The secularization thesis predicts that as societies become modern, religious authority will be replaced with public institutions. As Canada, and other countries develop, perhaps evolution will continue to favour secularization, demoting religion from its central place in social life, and religious conflicts to history textbooks and motel night tables.

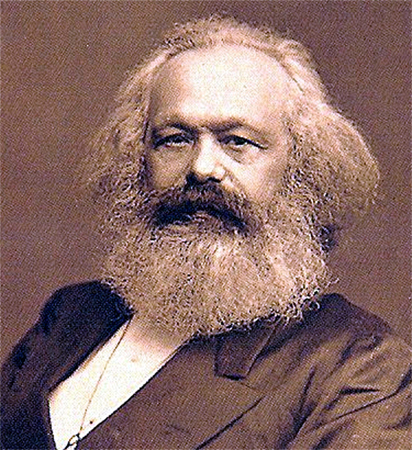

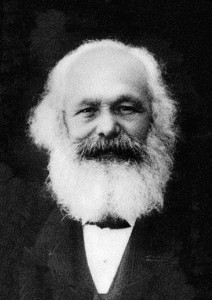

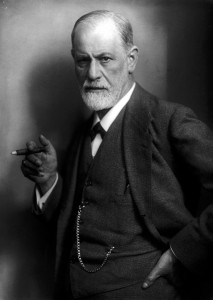

Karl Marx

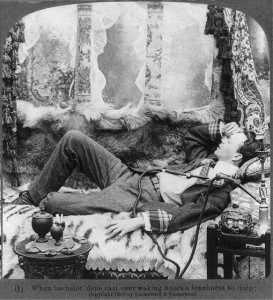

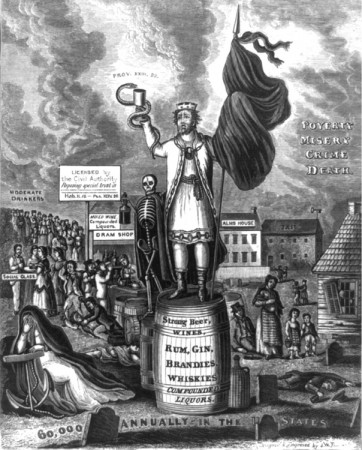

Figure 15.14. “When bachelor dens cast over waking hours a loneliness so deep.” Marx would have drawn from popular images of opium dens in formulating his famous phrase: “Religion is the opium of the people.” (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Where psychological theories of religion focus on the aspects of religion that can be described as products of individual subjective experience — the disposition towards self-transcendence, for example — sociological theories focus on the underlying social mechanisms religion sustains or serves. They tend to suspend questions about whether religious world views are true or not — e.g., does God exist? Is enlightenment achievable through meditation? etc. — and adopt some version of WI Thomas’s (1928) Thomas Theorem: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.”

From the point of view of the classical theorists in sociology, Thomas’s theorem was already implicit in the premise that the relationship to religion was a key variable needed to understand the transition from traditional society to modern society. Marx, Durkheim, Weber and other early sociologists lived in a time when the validity of religion had been put into question. Traditional societies had been thoroughly religious societies, whereas modern society corresponded to the declining presence and influence of religious symbols and institutions. Nationalism and class replaced religion as a source of identity. Religion became increasingly a private, personal matter with the separation of church and state. In traditional societies the religious attitude towards the world had been “real in its consequences” for the conduct of life, for institutional organization, for power relations, and all other aspects of life. However, modern societies seemed inevitably to be on the path towards secularization in which people would no longer define religion as real. The question these sociologist grappled with was whether societies could work without the presence of a common religion.

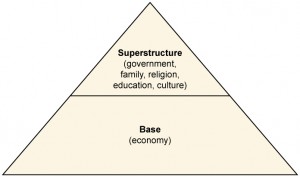

Karl Marx explained religion as a product of human creation: “man makes religion, religion does not make man” (Marx, 1844/1977). In his theory, there was no “supernatural” reality or God. Instead religion was the product of a projection. Humans projected an image of themselves onto a supernatural reality, which they then turned around and submitted to in the form of a superhuman God. It is in this context that Marx argued that religion was “the opium of the people” (Marx, 1844/1977). Religious belief was a kind of narcotic fantasy or illusion that prevented people from perceiving their true conditions of existence, firstly as the creators of God, and secondly as beings whose lives were defined by historical, economic and class relations. The suffering and hardship of people, central to religious mythology, were products of people’s location within the class system, not of their relationship to God, nor of the state of their souls. Their suffering was real, but their explanation of it was false. Therefore “religious suffering is at the same time an expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering.”

However, Marx was not under the illusion that the mystifications of religion belief would simply disappear, vanquished by the superior knowledge of science and political-economic analysis. The problem of religion was in fact the central problem facing all critical analysis: the attachment to explanations that compensate for real social problems but do not allow them to be addressed. As he said, “the criticism of religion is the supposition [or beginning of] of all criticism” (Marx, 1844/1977). Until humans were able to recognize their power to change their circumstances in “the here and now” rather than “the beyond,” they would be prone to religious belief. They would continue to live under conditions of social inequality and grasp at the illusions of religion in order to cope. The critical sociological approach he proposed would be to thoroughly disillusion people about the rewards of the afterlife and bring them back to earth where real rewards could be obtained through collective action.

The demand to give up the illusions about their condition is a demand to give up a condition that requires illusion…. Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers from the chains not so that man may bear chains without any imagination or comfort, but so that he may throw away the chains and pluck living flowers . The criticism of religion disillusions man so that he may think, act, and fashion his own reality as a disillusioned man come to his senses; so that he may revolve around himself as his real sun. Religion is only the illusory sun which revolves around man as long as he does not revolve around himself (Marx, 1844/1977).

Nevertheless, if Marx’s analysis is correct, it is a testament both to the persistence of the social conditions of suffering and to the comforts of holding to illusions, that religion not only continues to exist 170 years after Marx’s critique, but in many parts of the world appears to be undergoing a revival and expansion.

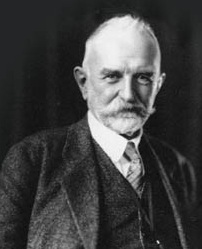

Emile Durkheim

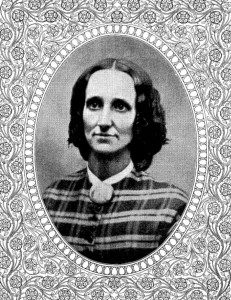

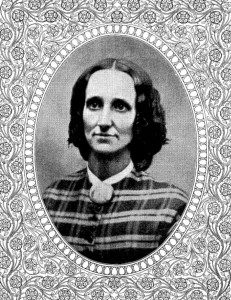

Figure 15.15. “Divine love always has met and always will meet every human need.” Mary Baker Eddy, founder of the Christian Science Church in 1879, describes divine love in terms similar to Durkheim’s functionalist theory of religion (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

Emile Durkheim (1859-1917) explained the existence of religion in terms of the functions it performs in society. Like Marx, therefore, he argued that it was necessary to examine religion as a product of society, rather than as a product of a transcendent or supernatural presence (Durkheim, 1915/1964). Unlike Marx, however, he argued that religion fulfills real needs in each society, namely to reinforce certain mental states, sustain social solidarity, establish basic rules or norms, and concentrate collective energies. These can be seen as the universal social functions of religion that underlie the unique natures of different religious systems all around the world, past and present (Sachs, 2011). He was particularly concerned about the capacity of religion to continue to perform these functions as societies entered the modern era in the 19th and 20th centuries. Durkheim hoped to uncover religion’s future in a new world that was breaking away from the traditional social norms that religion had sustained and supported (Durkheim, 1915/1964).

The key defining feature of religion for Durkheim was its ability to distinguish sacred things from profane things. In his last published work, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, he defined religion as: “a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden – beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them” (Durkheim, 1915/1964). Sacred objects are things said to have been touched by divine presence. They are set apart through ritual practices and viewed as forbidden to ordinary, everyday contact and use. Profane objects on the other hand are items integrated into ordinary everyday living. They have no religious significance. From Durkheim’s social scientific point of view, it is the act of setting sacred and profane apart which contributes to their spiritual significance and reverence, rather than anything that actually inheres in them.

This basic dichotomy creates two distinct aspects of life, that of the ordinary and that of the sacred, that exist in mutual exclusion and in opposition to each other. This is the basis of numerous codes of behavior and spiritual practices. Durkheim argues that all religions, in any form and of any culture, share this trait. Therefore, a belief system, whether or not it encourages faith in a supernatural power, is identified as a religion of it outlines this divide and creates ritual actions and a code of conduct of how to interact with and around these sacred objects.

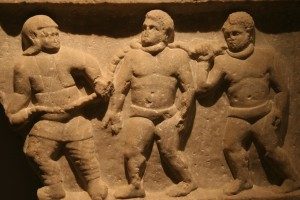

Durkheim examined the social functions of the division of the world into sacrd and profane by studying a group of Australian Aboriginals that practiced totemism. He described totemism as the most basic and ancient forms of religion, and therefore the core of religious practice itself (Durkheim, 1915/1964). A totem, such as an animal or plant, is a sacred “symbol, a material expression of something else” such as a spirit or a god. Totemic societies are divided into clans based on the different totemic creatures each clan revered. In line with his argument that religious practice needs to be understood in sociological terms rather than supernatural terms, he noted that totemism existed to serve some very specific social functions. For example, the sanctity of the objects venerated as totems infuse the clan with a sense of social solidarity because they bring people together and focus their attention on the shared practice of ritual worship. They function to divide the sacred from the profane thereby establishing a ritually reinforced structure of social rules and norms, they enforce the social cohesion of the clans through the shared belief in a transcendent power, and they protect members of the society from each other since they all become sacred as participants in the religion.

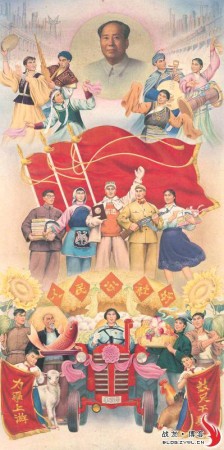

In essence, totemism, like any religion, is merely a product of the members of a society projecting themselves and the real forces of society onto ‘sacred’ objects and powers. In Durkheim’s terms, all religious belief and ritual function in the same way. They create a collective consciousness and a focus for collective effervescence in society. Collective consciousness is the shared set of values, thoughts, and ideas that come into existence when the combined knowledge of a society manifests itself through a shared religious framework (Mellor & Shilling, 1996). Collective effervescence, on the other hand, is the elevated feeling experienced by individuals when they come together to express beliefs and perform rituals together as a group: the experience of an intense and positive feeling of excitement (Mellor & Shilling, 2011). In a religious context, this feeling is interpreted as a connection with divine presence, as being filled with the spirit of supernatural forces, but Durkheim argues that in reality it is the material force of society itself, which emerges whenever people come together and focus on a single object. As individuals actively engage in communal activities, their belief system gains plausibility and the cycle intensifies. In worshipping the sacred, people worship society itself, finding themselves together as a group, reinforcing their ties to one another and reasserting solidarity of shared beliefs and practices (Mellor & Shilling, 1998).

The fundamental principles that explain the most basic and ancient religions like totemism, also explain the persistence of religion in society as societies grow in scale and complexity. However, in modern societies where other institutions often provide the basic for social solidarity, social norms, collective representations, and collective effervescence, will religious belief and ritual persist?