Creating Online Learning Experiences by Matt Crosslin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Creating Online Learning Experiences by Matt Crosslin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Creation of this resource was supported by Mavs Open Press, operated by the University of Texas at Arlington Libraries (UTA Libraries). Mavs Open Press offers no-cost services for UTA faculty, staff, and students who wish to openly publish their scholarship. The Libraries’ program provides human and technological resources that empower our communities to publish new open access journals, to convert traditional print journals to open access publications, and to create or adapt open educational resources (OER). Resources published by Mavs Open Press are openly licensed using Creative Commons licenses and are offered in various e-book formats free of charge. Optional print copies may be available through the UTA Bookstore or can be purchased through print-on-demand services, such as Lulu.com.

OER are free teaching and learning materials that are licensed to allow for revision and reuse. They can be fully self-contained textbooks, videos, quizzes, learning modules, and more. OER are distinct from public resources in that they permit others to use, copy, distribute, modify, or reuse the content. The legal permission to modify and customize OER to meet the specific learning objectives of a particular course make them a useful pedagogical tool.

Pressbooks is a web-based authoring tool based on WordPress, and it is the primary tool that Mavs Open Press (in addition to many other open textbook publishers) uses to create and adapt open textbooks. In May 2018, Pressbooks announced their Accessibility Policy, which outlines their efforts and commitment to making their software accessible. Please note that Pressbooks no longer supports use on Internet Explorer as there are important features in Pressbooks that Internet Explorer doesn’t support.

The following browsers are best to use for Pressbooks:

This publication was designed to work best online and features a number of hyperlinks in the text. We have retained the blue font for hyperlinks in the print version to make it easier to find the URL in the “Links by Chapter” section at the back of the book.

Information about open education at UTA is available online. If you are an instructor who is using this OER for a course, please let us know by filling out our OER Adoption Form. Contact us at pressbooks@uta.edu for other inquires related to UTA Libraries publishing services.

This book was created as a publication for the LINK Research Lab at the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA). The initial goal was to provide a resource for the faculty at UTA and many other institutions to utilize as they designed MOOCs and other online courses for LINK Research Lab programs – as well as for other departments and programs. In the spirit of openness and collaboration, that goal was expanded into making this book as general and context-independent as possible. Where specific needs for unique contexts were needed (for example, how to assess learners in a MOOC that might have thousands of learners), we have noted the specific contexts where they are most applicable. We also invited a wide range of authors and reviewers from different contexts and countries to add as many viewpoints as possible. However, we know that we are still falling short in many areas. If you see something you would like to add, improve, or expand, please contact us (matt@mattcrosslin.com). We would like to continually update this book with new, expanded editions in the future.

The first version of this book was more of a brief guide to dictate how instructors would create MOOCs for the LINK Research Lab at UTA. After the lead author wrote the initial handbook, additional LINK Lab personnel were brought in to add more sections. At the suggestion of George Siemens, we decided to expand the UTA MOOC Handbook to include all forms of online course design in as many contexts as we could cover (the original guide being focused entirely on public 4-year universities). This began the process of recruiting other authors and contributors- first from within UTA, and then from experts around the world. When the guide expanded to a book, the content was divided into chapters. However, the typical model of “one author writes one chapter” didn’t fit the best flow of the content. Therefore, we decided to move away from that model by allowing authors to contribute as much as they wanted – be it a chapter, a section, or a paragraph. Many people were invited, but we really only scratched the surface of those that we wanted to reach out to. Hopefully in the next edition we will get more of that list added. Also, we began to specifically reach out to people from different states, countries, and contexts from UTA to review the book for places we missed important contextual information. These reviewers gave us incredible feedback that improved the book immensely. The only regret was, again, time restraints, as we would have liked to invite so many more to review. Again, that will hopefully be improved upon in the next edition.

“Online learning experiences” is a broad term that covers a large number of contexts and possibilities. Not all ideas and processes covered in this book are going to work in every learning context. We encourage you to evaluate each idea presented against your specific needs and only use those that will work for you (but also, feel free to remix as needed). Additionally, please note that while those who are new to creating online courses might want to read the chapters in order, we tried our best to also design the flow so that you can move around the text in a non-linear fashion as well. Our goal with the structure was to have a flow that works for those that read the chapters in order, while giving the various sections and chapters a sense of independence for those that want to pick and choose (or for those that use this book more as a reference). If you find something we missed in this goal, please let us know.

Matt Crosslin is currently a learning innovation researcher with the UTA LINK Research Lab. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, games in learning, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.

The Lead Author wishes to first thank George Siemens, Laurel Mayo, Lisa Berry, and Justin T. Dellinger – directors past and present at the LINK Research Lab that mentored this project, gave me the go-ahead to do it in the first place, and continue to push the boundaries of learning research. This book also wouldn’t have reached publication without Michelle Reed of the UTA Libraries opening doors for it – thank you for answering my questions and fixing many things I got wrong (I promise no “s” on OER ever again). Thank you also to the authors, editors, and reviewers listed below – your time and contributions really took this book to the next level. Thank you for the awesome work – there was not a single “Reviewer #2” in the whole lot! To my current and former co-workers, colleagues, conference co-conspirators, faithful instigators on Twitter, consistent or occasional blog readers, and all the academics and professionals out there I follow (many I have never met in person) – thank you for providing deep insight and inspirational thoughts along our journey. You didn’t know that I was taking notes to make a book did you? I hope I did your ideas justice where I reference them here. If not – then come fix it in the 2nd edition! To my instructors at the University of North Texas, the University of Texas at Brownsville, and Baylor University – thank you for imparting to me a passion for education. Hopefully you see a lot of what you taught me in these pages. Of course, thank you to my Mom, Dad, and Brother for your love, support, and encouragement for my whole life. And finally, but most importantly, thank you to my wife Katie and son Riley – you both constantly inspire me to be a better person and care more about the world around us. I’m a lucky man to be around your support, love, and laughter every day!

Matt Crosslin, Ph.D. – Researcher, Learning Innovation and Networked Knowledge Research Lab, University of Texas at Arlington

Brett Benham, Ph.D. – Retired, former Technical Media Coordinator, Learning Innovation and Networked Knowledge Research Lab, University of Texas at Arlington

Justin T. Dellinger, M.A. – Associate Director, Learning Innovation and Networked Knowledge Research Lab, University of Texas at Arlington

Amber Patterson, M.A. – Marketing Coordinator, City of Mesquite, Texas

Peggy Semingson, Ph.D. – Associate Professor, Literacy Studies, College of Education, Curriculum & Instruction, The University of Texas at Arlington

Catherine A. Spann, Ph.D. – Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Colorado

Brittany Usman, M.S. – Instructional Designer, University of Texas at Arlington

Harriet Watkins, Ed.D. – Chief Academic Officer, Instructional Connections

Justin T. Dellinger, M.A. – Associate Director, Learning Innovation and Networked Knowledge Research Lab, University of Texas at Arlington

Rebecca Heiser, M.A. – Instructional Designer, Penn State University

Katerina Riviou – Ph.D. Candidate, Ellinogermaniki Agogi, Greece & Open University of Netherlands

Brittany Usman, M.S. – Instructional Designer, University of Texas at Arlington

Maha Al-Freih, Ph.D. – Assistant Professor, Princess Norah Bint Abdulrahman University

Maha Bali, Ph.D. – Associate Professor of Practice at the Center for Learning & Teaching at the American University in Cairo (AUC)

Autumm Caines, M.A. – Instructional Designer, St. Norbert College

Chris Gilliard, Ph.D. – Instructor, Macomb Community College

Rebecca J. Hogue, Ph.D. – Associate Lecturer, UMass-Boston

Whitney Kilgore, Ph.D. – Co-Founder & Chief Academic Officer, iDesign

Michelle Reed, M.S., M.F.A., M.A. – Open Education Librarian, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries

Sarah Saraj, M.Ed. – Instructional Design Manager, University of Texas at Arlington

George Siemens, Ph.D. – Director, Learning Innovation and Networked Knowledge Research Lab, University of Texas at Arlington

Harriet Watkins, Ed.D. – Chief Academic Officer, Instructional Connections

Thomas Perappadan, UTA Libraries’ OER Publishing Assistant, for assisting in the publication of this resource, and Kyle Pinkos, UTA Libraries’ Marketing Coordinator, for designing the cover.

The purpose of this book is to provide guidance and advice for instructors who would like to develop an online course. The overall goal is to provide some clarity about many of the steps required to propose and design a course, to describe the resources needed, and to explain the roles of the stakeholders. Online courses generally take much longer to develop than most people realize. The information in this book is very important in that it is based on practical experience gleaned from those that have designed and offered successful courses.

But why “learning experiences”? Most people think of learning in an official capacity as a course. The design of a course is often referred to as instructional design. Sometimes courses are designed by the instructor, but in other instances specific people other than the instructor provide the role of instructional designer. Over the past decade, changes to the online world have resulted in newer ways of thinking about learning that go beyond instruction and courses to learning experiences. Our hope is that, if you have already not begun to think in terms of learning experiences, that this book will help you transition your thinking in that direction(or continue to evolve it for those that have already started).

For many, the arrival of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) created a new paradigm of learning where some courses could be massive and open to anyone in the world (even though that had been happening in several places long before MOOCs were a thing). The other end of the spectrum from MOOCs would be small online courses with limited enrollment – which many think of as traditional online courses. Then there are many courses that fall in the middle of these two points: massive limited enrollment courses, small open courses, and so on. This book will cover as many issues common to all of those options as possible.

Good luck as you embark on or return into the world of online learning!

Modern online courses are an extension of older forms of distance learning, going back to mail and correspondence courses of the 1700s (Harting & Erthal, 2005). These courses were followed in the 1900s by radio, telephone, and television-based educational efforts (Harting & Erthal, 2005). Computers were used to deliver educational programs as early as the 1970s, even though the technology was often a hindrance. However, with the rise of personal computers, better Internet connections, and digital video technology in the 1990s, many universities began offering more courses online (Harting & Erthal, 2005). While this shift meant that online learning became more available to anyone with an Internet connection, these courses were often offered to select groups of learners. Starting in the 1970s and 1980s, various groups and universities began creating open learning or learning for all initiatives with the aim of taking learning beyond the silos it was often contained within (Harting & Erthal, 2005).

The first course to be called a “MOOC” was taught by George Siemens and Stephen Downes in 2008 (Kovanović, Joksimović, Gašević, Siemens, & Hatala, 2015). This course, Connectivism and Connective Knowledge (CCK08), was labeled a “Massive Open Online Course” after the fact by Dave Cormier. Attracting over 2200 students, CCK08 was really meant as an experiment in connectivism rather than massive learning. In 2011, Stanford University created their own MOOC – Introduction to AI, taught by Sebastian Thrun and Peter Norvig. This course attracted over 160,000 students, along with massive media attention as well. The New York Times called 2012 the “Year of the MOOC” because several well-financed MOOC providers came into existence, most notably Coursera, Udacity, and edX (Kovanović, Joksimović, Gašević, Siemens, & Hatala, 2015). Hype for MOOCs has died down since then, but there is still considerable interest in what they mean for education now and in the future. Despite the insistence of some, MOOCs will not destroy or disrupt universities, but they have already begun to make many examine exactly what teaching at scale means.

As MOOCs grew in popularity, different terms were created to label these different versions. The most useful were “xMOOC” – used to describe teacher-centric courses as “eXtension” of a traditional course – and “cMOOC” – used to describe more student-centered connectivist courses (Downes, 2013). Many other terms such as MOOC2.0, MOOC3.0, etc have been proposed, but these ideas have found little usage in most contexts. Another term that has been proposed is SPOC – short for “small private online course” (Fox, 2013). This term was first used for a more business-oriented approach of creating and licensing courses rather than what some refer to as “traditional” online courses that are also typically smaller and private (but not always).

Traditional online courses come in many varieties, from small cohort models to large “lecture hall” courses of hundreds. Some of them are also considered “blended” or “flipped” in that they meet partially in person and partially online. Some traditional online courses even integrate open features like Open Educational Resources (OER), social networking tools like Twitter, and collaborative learning. For the sake of clarity, in this handbook the term “online courses” will refer to any course that is offered partially or fully online to a specific set of learners (like enrolled learners at a University or company), while the term “MOOC” will refer only to those courses that are considered MOOCs. There are many places that regular online courses and MOOCs overlap, and many places that they differ. This book will explore both in the upcoming chapters, focusing mainly on regular online courses while highlighting any unique considerations for MOOCs as needed.

References

Downes, S. (2013, April 9). What the ‘x’ in ‘xMOOC’ stands for [Google+ post]. Retrieved from https://plus.google.com/+StephenDownes/posts/LEwaKxL2MaM

Fox, A. (2013). From moocs to spocs. Communications of the ACM, 56(12), 38-40.

Harting, K., & Erthal, M. J. (2005). History of distance learning. Information technology, learning, and performance journal, 23(1), 35.

Kovanović, V., Joksimović, S., Gašević, D., Siemens, G., & Hatala, M. (2015). What public media reveals about MOOCs: A systematic analysis of news reports. British Journal of Educational Technology. 46(3), 510–527.

Most (but not all) courses tend to be either focused on the instructor as dispenser of knowledge, or the learner as self-guided constructor of knowledge. Many courses are a mixture of both, but gravitate towards one side or the other regardless. Courses of any size can be either student-centered or instructor-centered, so you will first need to decide which direction your course will (generally) take.

The more the instructor focuses on themselves as the center of the course (some refer to this as “sage on the stage”), the more students will rely on them as the one to tell them everything… and to fix everything. This can be overwhelming in MOOCs with thousands of learners, but acceptable in smaller online courses with manageable numbers (although many topics in any course can still work well in student-centered approaches). The goal of any course should be to push learners into a place of learning how to learn about the course topic, so they can become self-directed learners (Kop & Fournier, 2011). This can also pose challenges for learners who were taught to focus on the instructor as the center of the class, or as the person to answer all questions. Instructors might also find it difficult to release the control over the class by letting learners take control (also sometimes referred to as “guide on the side”). However, we encourage you to keep self-directed learning in mind and work to move your course or your learners in that direction as much as possible.

Additionally, the massive nature of MOOCs and some larger online courses dictates that instructors will not have time to be the core of the course. Therefore, the design of the course will need to focus (as much as possible) on how to create self-determined learners simply out of practicality. Learners will need to begin to see other learners and the Internet as communities that are a source of answers and support (Hew & Cheung, 2014). For example, some courses have had success with creating voting systems that allow learners to post questions in the discussion forums and then allow other learners to “upvote” the ones that are most important. The instructor then answers the top questions each week. Other courses have encouraged learners to ask questions through social media outlets such as Twitter or Facebook, allowing instructors and other learners to answer as they can. Both methods have pros and cons depending on instructor’s available time as well as personal viewpoints of each method (various strategies to support each method are covered in this book).

The main concept to keep in mind is that MOOCs and larger courses can quickly become very student-centered in nature due to their massive size, and this often represents a major shift in power and control dynamics for many instructors. Be prepared for this shift. Also keep in mind that when teaching at this scale, learners don’t need you to just convey a bunch of factoids that they can look up online or in a book. They will want you to show them how to take control of the overall direction of their learning, something that is often referred to as “self-directed learning.” This is yet another large shift for some instructors. If these shifts are new for you, you might want to look into a field called heutagogy, which is this the study of self-directed learning (Blaschke, 2012).

Another major factor about your course that will affect many decisions is whether or not learners will be interacting with each other and/or the course synchronously or asynchronously. Synchronous courses are basically those courses that have learners meeting with each other and the instructor(s) in real time in the same space. That space may be a physical classroom, a video conference tool, or even a text-based chat tool – but the key is that learning experience for each participant is synchronized with the other participants. Typical on-campus college courses are often seen as synchronous – learners consume the materials (lectures) at the same time and place, discuss course topics during class time, and complete assignments like tests in class. Asynchronous courses are those that do not require learners to meet in the same space at the same time. Typical online courses are often seen as asynchronous – learners consume the materials at different times, post to discussion boards at the different times, and complete assignments at different times.

However, these are often not completely separate constructs. On campus courses can have online asynchronous components added for after class work. Online courses can have synchronous video chat sessions or live lectures mixed in with asynchronous discussion boards. Sometimes these mixtures are determined by company or institutional policy, other times they are left up to the instructor. If these decisions are left to you, you will need to decide what mixture is right for your course and your learners (keep in mind that sometimes the ideal solution for the course is not ideal for specific learners – in this case, try as much as possible to go with what is best for the learners).

Much of what you read for the rest of this book will also need to be filtered through how much of your course is synchronous and how much is asynchronous. For example, if your students are working adults that need maximum flexibility, you might decide to make your course entirely asynchronous. This would probably mean that you would not spend much time on tools that enable video conferencing. However, no matter what the mix of synchronous/asynchronous ends up being, you should keep in mind you are still dealing with humans. Your course designs will need to keep the human element in your course in mind while designing for either modality. One good resource to read about this topic is an article called “Bringing out the Human in Synchronous and Asynchronous Media for Learning” by Maha Bali.

Much can be said about the underlying theoretical foundations of learning. Many, many books and articles have been written on the topic, so this is not an area that can easily be skimmed lightly. However, it can be of benefit to your course for you to think through what your theoretical goals/desires/requirements are for your course, and then to design appropriately after clearly setting your expectations. Therefore, a basic overview is presented here.

Looking at learning as either instructor-centered or students-centered is a good place to start, but it can get much more complex than that. For the sake of space, we will expand this list to three possibilities:

Each is actually more complex than the provided definitions, and there are various other areas that fit in between, beside, and outside of these. These terms could also be considered basic power dynamics that describe who is in control of learning in your course.

Intersecting and sometimes paralleling these power dynamics are teaching methodologies for designing the course itself. Again, there are many of these that could be listed, but we will stick with a simplified list:

Again, these are simplified definitions rather that specific descriptions that cover every aspect of these terms. The power dynamics and methodologies mentioned also tend to blend into each other as well. They can also be combined and arranged in a grid-like pattern to help you get even more specific about the design of your course:

Instructivist Pedagogy Formal learning that depends on the instructor to dispense knowledge that is new to learners. Focused on content, video, standardized tests, papers, and instructor-guided discussions. | Instructivist Andragogy Experienced learners are heavily guided through discussion activities to add to existing knowledge. Instructors guide learners through lessons learned by other experienced people in the field. | Instructivist Heutagogy Probably a very unlikely design to attempt, but this would basically be an expert sharing information about where to learn about a topic. Contains mostly lists of resources and professional communities that learners can join into to learn more, as well as instructions on how to best interact with resources and communities. |

Constructivist Pedagogy Learners build upon existing knowledge and experiences by formally learning from more experienced others individually or as a group. Instructors create scenarios and activities for learners to reflect on what they know and construct new knowledge in their own ways. Writing, blogging, and reflective activities of all types are most common. | Constructivist Andragogy Learners build upon existing knowledge and experiences to construct new knowledge either individually or as a group. Group work, open-ended reflection or discussions, and project-based learning are common types of activities. | Constructivist Heutagogy Learners constructing a way to learn about a topic either individually or collectively as a group. Ill-structured problem-based learning, open ended group activities, and web searches focused on how to learn more than what facts to learn about a topic are possible activity types. |

Connectivist Pedagogy Learners working in a network in a formal sense to accomplish an ill-defined competency as created by the instructor. The instructor’s knowledge would be the main focus and driving force behind this design. | Connectivist Andragogy The goal of learning is to work as a network in an informal sense to accomplish a competency that might be somewhat suggested by the course or instructor, but is ultimately determined by the group and based up expanding upon life experiences. | Connectivist Heutagogy Learners working as a network to figure out how to become a learner about a topic. The instructor might create the avenue for connections and then become one equal part of the network. See the rhizomatic model of education as a possible example, where curriculum is constructed by the engaged learning community (Chapter 13). |

This section and the above chart are adapted from a book chapter entitled “From Instructivism to Connectivism: Theoretical Underpinnings of MOOCs” (about MOOCs, but could apply to any online course as well – see list below), which would serve as a good resource to explore the overall idea in more depth. Keep this section in mind when looking at the section on “Clear Communication” and “Types of Communication” later in this manual, as it will continue this look at theory as applied to communication. For more resources on some of the theories touched on here, see:

All courses set out to have learners learn something through a transfer of knowledge and/or skills. However, different teachers at different institutions will have different methods for how they teach that something. Once you know what you want your learners to learn, you need to start planning how you are going to teach it or how your learners are going to learn it, depending on where the focus of your course is. Creating well-written statements on how learning occurs will not only help you design your course, but also will help your learners understand what is going to happen in the course of learning.

Many words are used for these statements: goals, objectives, outcomes, strategies, competencies, etc. Some see many of these words as interchangeable. For the sake of this manual, we will focus on three:

As an instructor, you may already have a good idea of the goals, objectives, or competencies you will use in your course. They may have been given to you by your institution or company. Or you may have never thought about any of them. Generally, you will want to have at least a draft of these written out before you design your course (they can, and probably will, change during the design process). On the other hand, you may want to let your learners determine the goals and objectives for the course (or even to map their own competencies as the course progresses). Even if that is the case, you will still want to be familiar with how to create goals, objectives, and competencies in order to lead your learners through the process. Much has been written on how to write effective goals, objectives, and competencies. We will only cover the basics here, but if you need to go more in depth, there are many resources online to look into.

The important thing to remember in writing goals is to not confuse them with objectives and competencies. Remember to keep them general and overarching for the course, but not so general that they basically just say “Students will learn _______ [topic of the course]”. Try to think of what students will learn rather than a list of topics. You can do this by looking at your course backwards – what will learners have accomplished by the end of your course? Focus on what learners will be doing rather than the topic. Make sure that learners can understand them (aka avoid jargon). For more details, see:

There are many different ways to structure objectives, but we recommend a good starting place is with the Behavior/Conditions/Criteria structure. In this structure, objectives should start with the behavior – what students will be able to do (“create a timeline of historical events that led to World War I”). Then add a condition – how they will be able to do it, usually added before the behavior in a written objective (“After reading the chapters on World War 1”). Finally, follow all of this with the criteria – the method for determining how they demonstrated mastery of the objective (“by correctly answering 70% or more of the questions on the World War 1 test”). Be sure to avoid unmeasurable words like “understand,” “know,” or “appreciation for” in the behavior; make sure that each objective feeds into the goal; and ensure that every goal has a good number of objectives to support it. If not, revise your goals and/or objectives. For more details, see:

Just like objectives, competencies can be approached and structured in many different ways. They are sometimes utilized in more standard learning situations, or can become the central structural feature of learning in competency-based learning. There are typically three concepts to keep in mind when creating competencies. First, competencies should be focused on the learner, rather than on the content or you as the instructor. Make sure that you are creating a way for learners to focus on their individual needs as they collaborate or work with others. Second, competencies should focus on outcomes over course structure. Many courses start with a “topic per week” approach and build out from there, but competencies may take more or less time than a week to complete. Third, competencies should be able to adjust and flex with the different individual needs of individual learners. Objectives tend to create one set of standards for all learners to attain in the same manner, whereas competencies tend to provide flexible structure for learners to personalize the learning experience to their needs and contexts. For more details, see:

Competencies tend to work best when situated in an overall context of competency-based learning. While there is disagreement over some of the specifics of competency-based learning, there are a few key concepts that generally tend to differentiate it from more traditional course structures. The biggest key concept is flexibility. Competency-based learning tends to allow learners to determine what exactly they are going to learn about a particular topic, how long they need to learn it, and how they will demonstrate that they have mastered the topic. Learners also typically do not advance until they have proven mastery, unlike traditional learning scenarios where all learners advance based on the calendar regardless of mastery. Additionally, class structures and organization as well as content or activities can be adjusted by individual learners to fit their specific social, cultural, and learning contexts and needs. For more details, see:

Once you have created your goals, objectives, and/or competencies, keep these at the forefront during the entire course development. Everything that goes into the course needs to relate back to these.

When all of these items (course content, learning activities, and assessments) are aligned with the goals, objectives, and/or competencies, they will work to reinforce one another. Conversely, if any of these items are misaligned, it can lead to learner frustration. This may be realized if a learner says “The readings did not prepare me for the test.” What may have gone wrong if a learner says this? Consider this quote: “If you design assessments as an afterthought at the end of designing the instruction (a common but unfortunate mistake), you are likely to design the wrong content and the course activities and the assessments are likely to be far less meaningful or appropriate” (Shank, 2006). This is exactly what courses that are not aligned look like. You are giving learners puzzle pieces that don’t line up. It may be that the instructor created learning objectives but then chose content that they found interesting, but that was irrelevant to the objective. Then, they designed an assessment based on that misaligned content. Since the content was irrelevant to the objective, the assessment, in turn, is not going to evaluate whether the learner mastered the objective.

A good practice to ensure you are aligning your content is to create a course map. A simple table to show how each objective or competency is aligned with goals, content, technology, learning activities, and assessments will help visualize the alignment. An example table is provided below.

| Specific objective or competency | Course goal | Content | Technology | Learning Activity | Assessment |

| Enter one objective or competency per row. | List the broad course goal(s) that the specific objective or competency relates to. | List all content (text, video, etc.) that learners will use for this specific objective or competency. | List any technology required for the course content that was listed. | List any practice activities. For example, reading or watching the course content, or completing practice questions. | List any assessments where learners will demonstrate their mastery of the specific objective or competency. |

As you work through theory, goals, etc., one idea to also consider with your course is openness. Openness is often connected with MOOCs today, but the truth is that any course can be open or even have open elements. Even though the second “O” in MOOC is “Openness,” many don’t realize that it means more than “free” or “anyone can sign up.” Traditional online courses can also incorporate many aspects of openness even if the course itself is not considered “open.” In fact, many instructors like to include aspects of openness in their traditional online courses.

A course that is completely “open” means many things, including that the content is freely accessible for all (Rodriguez, 2013). What that statement means is that videos can be downloaded, PowerPoints used in videos can be downloaded, all learning materials to be used are available for free, all content is available from the beginning of the course, and learners still have access to the course indefinitely after the last course day. This can be a major paradigm shift for those that are used to teaching in a closed course online or face-to-face. The expectation is that anyone can access any part of the course at any time, and even in some cases re-use or remix the content in their courses. This would limit using expensive textbooks, tools, or websites that have commonly been used for years in education. This may also mean using open-source solutions outside of the ones offered officially on campus. The main idea to keep in mind is that if a course is considered to be “open,” there would be few restrictions on who can access any portion of it. This leads to certain freedoms and certain problems, as will be discussed in later sections.

However, if certain institutional limitations prevent complete openness, many courses can implement some aspects of openness as desired or allowed. This is up to the instructor (or course designer if there is someone designated for that role specifically), but just keep in mind to keep the course completely open if referring to it as a MOOC.

The major issue to consider in relation to openness is licensing and permissions. Certain forms of copyright are very restrictive, and therefore not completely “open.” For many, your institution or company will already have made decisions on how the content and activities (text, image, video, etc.) you have created will be licensed. For others, you may have some or total freedom to license the content and activities that you create as you like. If you decide to use any type of open license for your content and activities, this could increase the impact and spread of your content outside of the course, as well as make it accessible to more learners. Just keep in mind that materials put into closed LMS systems under “fair use” cannot be turned into open content without permission from the copyright holder of that material. For more information on open licensing, see the section in Chapter 8 on Open Educational Resources.

One aspect of openness that all courses must take into consideration, regardless of size or theory or where/how the course is offered, is accessibility. Certain learners have various considerations when interacting with online courses due to disability, socioeconomic situations, or any number of other factors. You may work at an institution or company that has staff to ensure your courses are as accessible as possible. If that is the case, then you must listen to everything they tell you to do with your course. Accessibility design is not only a good idea, it is usually also the law.

If your institution or company does not have a person or department to ensure that your course is fully accessible, it will be up to you to do so. Even if you have someone else to review your course, designing with accessibility in mind can typically save a lot of time in the long run. You will find that it is better to design your course right the first time than to spend a lot of extra time correcting accessibility issues later on.

Different tools have different accessibility standards that often evolve as technology changes. The best thing you can do is search for accessibility guidelines for the tool you wish to use (“accessibility standards for Word docs,” “accessibility standards for online videos,” etc). Also keep in mind the tools that your learners might use, such as screen readers. A screen reader is an assistive device that attempts to convey what is on screen to people with various sight and reading issues. Different screen reading devices have different abilities to convey what is on the screen, so try to keep tools like that in mind when designing course materials. Here are some general guidelines to keep in mind about accessibility (others will be covered in later chapters as well):

Depending on where you want to teach the course, or what tools you use, there may be other accessibility issues you need to look into. The list above is not an exhaustive or complete list, so be sure to do some research and check to make sure you are up to date on all accessibility issues that apply to your course. Here are a few places to start learning about accessibility:

MOOCs are can sometimes be very different from regular online courses, which in themselves are different from on campus face-to-face courses. You should have at least several years’ worth of experience designing and offering traditional online courses before offering a MOOC. However, even extremely experienced online instructors will find many new challenges to face in their first MOOC. Some basic differences include:

With this in mind, there are several questions that you as an instructor should ask yourself before deciding to offer a MOOC. What goals do you have as an instructor that led you to choose a MOOC over other course formats? Is a MOOC the best option given those goals? What are your motivations for using a MOOC? Will a MOOC help or hinder those goals? With those questions in mind, consider what can and can’t be accomplished with a MOOC:

Many of these issues and differences stem from the openness of MOOCs. Open means much more than just being “free to anyone that wants to sign up,” as was examined in the previous section on Openness.

References

Blaschke, L. M. (2012). Heutagogy and lifelong learning: A review of heutagogical practice and self-determined learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(1), 56-71.

Hew, K. F., & Cheung, W. S. (2014). Students’ and instructors’ use of massive open online courses (MOOCs): Motivations and challenges. Educational Research Review, 12, 45-58.

Kop, R., & Fournier, H. (2011). New dimensions to self-directed learning in an open networked learning environment. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 7(2), 2-20.

McAuley, A., Stewart, B., Siemens, G., & Cormier, D. (2010). The MOOC model for digital practice. Retrieved from http://www.davecormier.com/edblog/wp-content/uploads/MOOC_Final.pdf

Milligan, C., Littlejohn, A., & Margaryan, A. (2013). Patterns of engagement in connectivist MOOCs. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2), 149-159.

Rodriguez, O. (2013). The concept of openness behind c and x-MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). Open Praxis, 5(1), 67-73.

Shank, P. (2006). To plan good instruction, teach to the test. Online Course Design: 13 Strategies for Teaching in a Web-based Distance Learning Environment, 8-9. Retrieved from http://hilo.hawaii.edu/academics/dl/documents/13StrategiesforTeaching.pdf

While online courses could potentially cover any topic, your institution or company may have a specific niche within the online learning world that they focus on. Or you may have the freedom to cover any topic you like. Either way, there are several areas related to online course design that you should be familiar with before you propose and create a new course.

Both regular online courses and MOOCs should be expected to be held to the same high quality standards as traditional in-person courses. This means that time and resources should be allocated to create the best possible course experience for learners. This includes, but is not limited to:

A note on MOOCs: even though MOOCs are offered for free, you cannot skimp on quality. These courses are broadcast to anyone in the world, and therefore serve as the visible face of your institution or organization for many that have never heard of it. Please ensure that all parts of the course are of the highest quality possible.

An important step in any creation process is the evaluation of the final product, or quality assurance; and this is true for course design as well. All online courses are generally expected to be held to the same high quality standard of traditional in person courses, especially at institutions that are accredited by any external accreditation group or board. This means that time and resources should be allocated to create the best possible course experience for learners.

What, or who, determines elements of a quality course? Rather than reinvent the wheel, a popular option is to utilize quality standards that have been developed by nationally recognized organizations, such as the Quality Matters Rubric or the Online Learning Consortium (OLC) Quality Course Teaching and Instructional Practice Scorecard. Once you have decided which standards you would like to follow, it is important to implement them during course design, rather than checking for them at the end of course design.

Implementing quality standards into a course can yield benefits for both the instructor and student. For example, in regards to course design (layout, organization, and navigation), participants rated courses with high findability as a better overall experience. Students reported lower levels of self-efficacy and motivation after interacting with courses rated low in findability (Simunich, Robins, & Kelly, 2015). When it is clear to learners how to navigate the course, where to find materials, and how to submit assignments, learners have to ask fewer procedural questions and the course is easier to manage for the instructor. The instructor could even have more time to provide quality feedback to learners (of which learners crave) versus spending time answering procedural questions.

Some questions you will see addressed in popular quality standards are listed below. This list is a very high-level summary – there are many more details to consider within these topics. For example, the Quality Matters rubric has 43 standards and the OLC Scorecard has 97 standards.

Course Design

Course Objectives

Clarity

As a note, clarity is an important component of online course design which will be covered more in Chapter 5. In contrast with in-person courses, online learners cannot seek immediate clarification for instructions that are not understood. A delay in clarity can cost online learners valuable time. Therefore, you will see many standards that reference being “clear” or “clearly stated”.

Engagement

Student Support

Accessibility

All online courses offered through any institution or company will be required to adhere to all applicable institutional or corporate course policies and requirements. There may also be a specific group in charge of regulating online course quality at your institution or corporation. But even if there is not one specific group in charge of regulating course quality for you, you are highly encourage to follow all suggestions in this manual and to seek out feedback from trained instructional designers. Additionally, you will be expected to know and adhere to all policies and requirements of any service that you utilize in your course (Blackboard, edX, Google, Facebook, WordPress, etc.). Please be sure to familiarize yourself with any service you wish to use before using them.

Creating an online course can be a major undertaking that will require a large team of people. Unless your institution currently has anyone working on course design full time, your team will consist of people who are working on your course in addition to other duties. If your institution or company does not provide team members for you, you should consider recruiting from people whose normal job duties cover various aspects of online course creation (as their workloads allow). This team will include, but is not limited to:

Your institution or company may already have a platform (sometimes called “LMS” for “learning management system” or “CMS” for “course/content management system”) for hosting courses that you are required to use. For a traditional online course, these could be something like Canvas, Blackboard, or Moodle. For a MOOC, that could be something like EdX or Coursera. Additionally, there are other options out there, including using open source platforms such as WordPress to host content. If you do not have one of these services as an option, there are a few possibilities to host content:

Please note that you will need to choose a platform that matches the openness of your course. If you want to run a MOOC or have open material in any online course, the closed nature of many LMS tools like Blackboard may not make them a good tool for offering open content or courses. On the other hand, if there are reasons you are choosing to limit access to your course to only those that register for it (like sensitive course content or institutional requirements), the open nature of services like EdX may not make them a good choice for your course.

One growing trend in education is the exploration of data that online learning tools generate in an analytical way. Whether you or your users realize it or not, everything that you do online is usually recorded in a database somewhere. This data has typically been locked away from everyone (except for the company that collected it), but that is starting to change.

Most of the tools that you can use in online learning – from WordPress to EdX to Canvas to Blackboard – will offer you the ability to see some kind of analysis of the data activity in your course/website account/etc. If you use that analysis to improve your course or influence your learners, those actions move into the realm of Learning Analytics. Your institution or company may require that you use analytics, and even provide deeper results from companies like Civitas. On the other hand, your institution or company may not even know this data exists.

The study of learning analytics is still a newer field with many unknowns. However, there is interesting work occurring in the field as it grows. For a good overview of the field, we recommend The Handbook of Learning Analytics edited by Charles Lang, George Siemens, Alyssa Wise, and Dragan Gašević. This handbook “is designed to meet the needs of a new and growing field. It aims to balance rigor, quality, open access and breadth of appeal and was devised to be an introduction to the current state of research.”

The most important concept to keep in mind about learning analytics is that the data being analyzed contains sensitive personal information covered by many legal guidelines. Ideally, you and your learners will be fully informed about what is collected, how it is collected, what is done with it after it is collected, and so on. Additionally, the ideal legal scenario is that you and your learners would choose to “opt in” to allowing this collection if you agree with having your data utilized in this manner.

However, the more likely typical scenario is that little clear information is given to end users about data collection, with users being put in the position of having to opt out of data collection (or even worse, have no way of opting out if they want to get into a course). If this is the case with the tools you use, we would suggest that you take the initiative to clearly communicate with learners everything you can discover about data collection in every tool you use, including how to opt out if they so choose. Data collection in education is a controversial topic, so it is best to be open and clear as much as it is possible within your context.

Many reasons exist for considering the ethical dilemmas within learning analytics. For example, looking at the data the wrong way could lead to profiling learners unfairly. Additionally, the algorithms used to create the analytics will carry with them the bias of those that created them. Learners are always unique individuals that can defy the classification systems that analytics utilize. For more information on these issues, as well as ways to ethically use learning analytics, see this article:

Many tend to think of technology, algorithms, and analytics as neutral entities that do not have programmed assumptions, contexts, and biases in them. However, this is not the case. All software has been found to reflect, in small and large ways, the biases and assumptions of those that created it (VanderLeest, 2004). This does not necessarily mean that you should never use these tools, but you should think through what these programmed biases are and what they mean for how you use them in a course (as well as how and what you communicate about those tools to learners).

For example, “personalized learning” is a current buzzword in online learning circles, with many organizations putting large amounts of money into the concept. Those organizations have goals behind the money they put into their products, and biases for and against certain philosophical schools of thought. For instance, see this brief examination of some the ideas shaping personalized learning in some of the largest donors to the concept:

The way that personalized learning is being shaped may or may not disagree with your vision of learning, however, you should know how it is being shaped before using any tools connected to these organizations. You should also take those influences into account when utilizing tools and communicating about those tools to learners.

An even deeper ethical consideration to explore is how inequalities are part of the very fabric of the Internet itself. Some think of this in terms of a digital divide. A better concept to examine would be digital redlining: “the creation and maintenance of technological policies, practices, pedagogy, and investment decisions that enforce class boundaries and discriminate against specific groups.” This definition comes from this article that looks deeper into problems inherent in the Internet itself:

Since this is an ever-evolving issue in education across hundreds of technologies, resources, websites, concepts, hardware, etc, you will need to do some searching for the specific tools and ideas you want to use in your course, or that pertain to your context. For instance, if you work in “for profit education,” you probably should familiarize yourself with the work of Tressie McMillan Cottom in LowerEd (although she also covers many other topics you should be aware of). The work of Audrey Watters at Hack Education covers multiple ideas and technologies in education from a historical critical lens. Chris Gilliard’s work in Digital Redlining and Student Framing is also a good place to start. For international views on technology issues, Maha Bali covers a wide range of issues that many in the West often fail to consider. Many others are out there, start following these four on Twitter and see who they quote there as well. Additionally, for a deeper dive into how biases are built into algorithms, see Algorithms of Oppression by Safiya Umoja Noble.

References

Lang, C., Siemens, G., Wise, A., & Gašević, D. (Eds.). (2017). The Handbook of Learning Analytics. Society for Learning Analytics Research (SoLAR).

Simunich, B., Robins, D. B., & Kelly, V. (2015) The impact of findability on student motivation, self-efficacy, and perceptions of online course quality, American Journal of Distance Education, 29(3). 174-185, DOI: 10.1080/08923647.2015.1058604

VanderLeest, S. H. (2004, June). The Built-in Bias of Technology. In Proceedings of the 2004 American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) Conference (pp. 1417-1427).

Once you are familiar with online learning in general and the tools you will need, you will need to decide if a MOOC or a regular online course is the right choice for you. Once you have decided which the best choice is, the next step is to begin the official proposal process.

All proposed online courses will probably need to have the approval of someone before offering the course: a Director, a Dean, and/or a department head of the College or department to be offering the course. Online courses require extensive resources that must be covered by the instructor’s organizational oversight. Please have the proposal approved as you would any other courses through your department or company.

Ideally, a proposal for a new course will need to be submitted as soon as possible, at least one year before the course is offered. Minimum proposal lead time for shorter courses that are focused more on interaction (and therefore require less media production) could shorten the due date for proposals to six months.

Additionally, you will need to have already recruited a course design team as well as decided on which platform(s) to utilize in your course. If your institution or company does not offer these services for you, you should recruit from people you work with whose normal job duties cover various aspects of course creation (as their workloads allow). You may also seek out grants and teaching assistants to assist you as your department or college allows. The course design team should be noted on the proposal form.

Also note that a timeline for the creation of the course should be submitted with the proposal. In your proposal, you may also wish to include a reference to any quality standards you will utilize to evaluate the course. Online courses are generally expected to be completely ready to go by the first day the course is offered, so please plan to finish your design and pre-planned content and activities well before the first day of course (be sure to build in a few weeks at the end of the development process for quality review as well, depending on your review process). An orientation week before the course starts is a good idea for working out any kinks with your learners.

Once a course has been approved, the creation process should begin immediately – within one week of the approval or less. This will include:

Within one month of approval, you should have at least one full module or week completed (including videos and graphics). This should be submitted to your departmental/organizational oversight or an instructional designer for review.

Within half the time between approval and when the course starts (ideally six months before the course begins), you should have at least half of the course completed (including videos and graphics). This will be submitted to your departmental/organizational oversight or an instructional designer for review. However, your departmental/organizational oversight or instructional designer may request more frequent updates for more complex courses.

One month before the course begins, everything for the course should be complete and ready to go. This should be submitted to your content and design reviewers for full review.

Any issues identified in the full review should be addressed by one week before the course begins.

Additionally, we recommend that sometime within one week before the course begins that you open the course for a test run with any interested learners to ensure there are no final issues.

The course development plan should include assessment and review of your course design. Your instructional designer should include this in the course design, but it may also require additional resources from you as the instructor. If you do not have internal quality standards to follow, you can utilize national quality standards, as referenced in the “Quality Review” section of Chapter 3, during both formative and summative assessments.

Formative Assessment is basically a review of the course content and design as the course is being designed. You should probably have at least one colleague review the content of your course several times to give you feedback on issues such as clarity, ease of navigation, content alignment, workload balance, and technical concerns. Additionally, the instructional designer will need to have at least one other instructional designer review the design of the course several times to provide feedback on the overall course design. One helpful suggestion for quality assessment is to first develop only one module or week of content and submit it for a formative review. This initial review should provide feedback in regards to the quality standards you have selected to follow. Then, take the feedback received and implement it as you continue the design of the course.

Summative Assessment is basically review of the course after it has been offered. This could consist of grades, participant feedback, or course data. Most of this will not magically appear, so you will need to plan for feedback as part of the design process. Course participant assessment techniques will be covered later in this book. Participant feedback can be gained from several sources, including Twitter feeds, pre- and post-course surveys, and forum posts. Course data can include all types of electronically collected information, from clicks on content links, to time spent on specific pages, to profile information. You will need to contact the course platform you use for specific details on what data is collected and how you access it.

Not only is course design assessment a good source for data in published papers, but it is also a good place to gain insight into how to update your course before offering it again. For example, you can review how well your student activities and assessments reflected the quality of the learning objectives based on what the results of summative assessment tell you. No course is perfect the first time it is offered, so updates and changes are expected after each offering.

In general, there are many different ways to design online courses that work in different contexts, and many ways to design online courses that do not work in various other contexts. We are avoiding the term “best practices” here because online teaching and learning can vary in different contexts, making “best” a problematic term. We can offer a list of some things that we know will usually work better in most online courses:

Speaking of clear communication, we should take a minute to highlight that clear communication is important for all aspects of education. Communication is a foundational element of educational theory (Warren & Wakefield, 2012); without clear communication, learners can feel confused and discouraged. Many different theories of communication exist; the important thing is to pick one that works and stick with it. For those that need some guidance, one suggestion is the Learning and Teaching as Communicative Actions (LTCA) theory developed by Dr. Scott Warren from the works of Jurgen Habermas. LTCA theory basically breaks educational communications down into four communicative types:

The important aspect of LTCA theory (or any other theory you choose to use) is to evaluate what you are trying to communicate in various parts of the course and then make sure to communicate effectively without confusing communication styles. For example, don’t set up a blogging assignment that would require students to use dramaturgical communicative actions and then create long, detailed instructions requiring learners to use strategic communicative actions.

For more information on LTCA theory, see the theoretical framework sections of the following articles:

Communication is an aspect of teaching that we all know happens, but many do not think fully through what that means. The types of clear communication you will want in your course will most likely flow from the underlying theories you subscribe to for the power dynamics and methodology of your course (see the previous “Theoretical Foundations of Learning” section). Looking across the literature, various researchers (Moore, 1989; Hillman, Willis, & Gunawardena, 1994; Anderson & Garrison, 1998; Dron, 2007; Wang, Chen, & Anderson, 2014) have identified at least 12 types of communication types that can happen in education:

Some courses will have one communication type for the entire class. Others will have a few types, while still others will have different types for each activity. Also, while some types of communication like “student-teacher” may lean towards certain power dynamics like instructivism, that does not have to be the only possibility. For example, student-teacher interactions could be constructivist if the student is teaching the instructor, or possibly even connectivist if a learner is bringing their instructor into a networked learning experience.

The important issue to think through is what kind of communication types you will need to accomplish clear communication in the power dynamics or methodologies you desire for your course, and then which communication types will you need for individual assignments in your course. For a discussion on applying power dynamics, methodologies, clear communication, and communication types to specific assignments, see the later section on “Connecting Activities to Theory and Communication”. Additionally, for a deeper discussion of the communication issues touched on here, see the communication sections of “From Instructivism to Connectivism: Theoretical Underpinnings of MOOCs” by Matt Crosslin.

Many instructors like to have a well-structured and planned out course, while others prefer varying levels of flexibility to change the course content, structure, and/or activities based on many factors (such as current events, flexible lesson schedules, learner interest, etc). When we refer to having a course completely designed and reviewed by the first day of class, this refers to all of the content and activities that you already know will be a part of the course. For some courses, this will be all of the content and activities. For other courses, this is more of a “plan” or “outline” of what could happen depending on various factors.

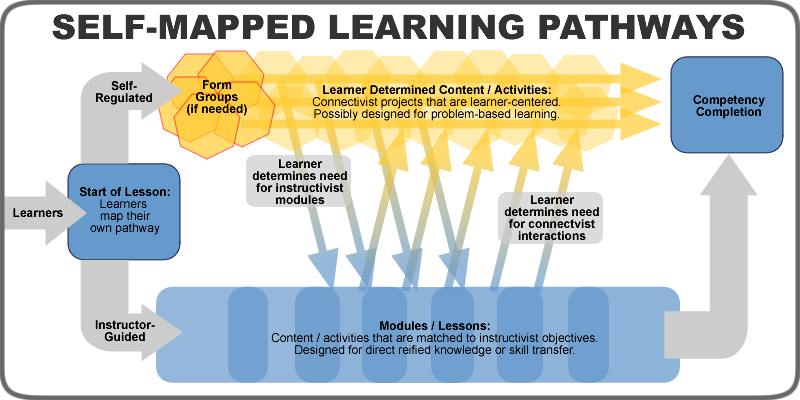

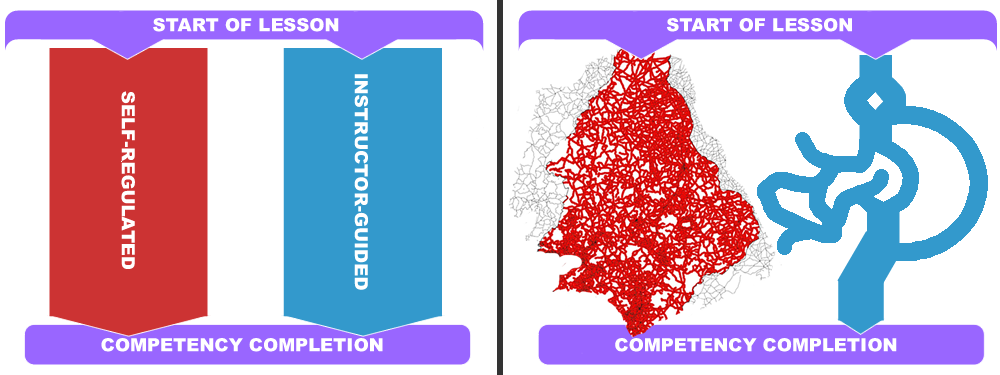

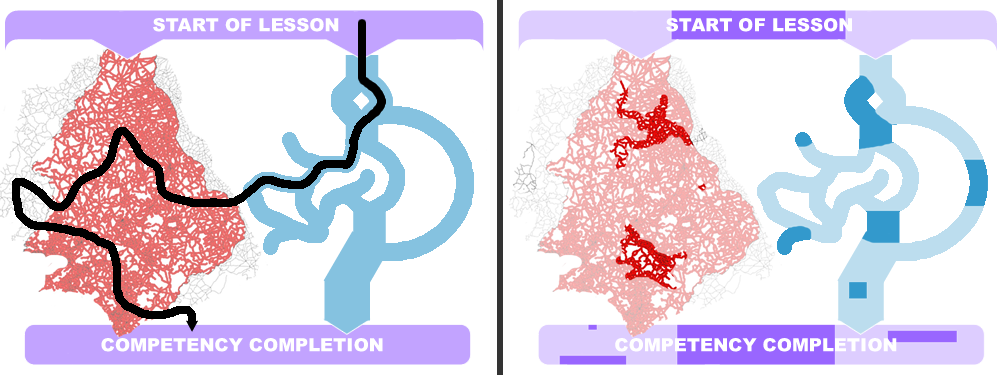

Planning for flexibility in your course can be challenging, but the benefits will often make up for the difficult parts. Mia Zamora and Alan Levine refer to this as building a “Course Spine” that outlines the major course elements, but leaves room to fill in details as the course progresses (Levine, 2018). Other ways of looking at this concept include “student-centered learning” and “problem based learning” depending on how the course is structured. Various ways to design your course to utilize these ideas will be explored throughout this book. Additionally, Chapter 13 is dedicated to more advanced course design methods that fall into these categories, such as Self-Mapped Learning Pathways and Rhizomatic Learning.

One thing to keep in mind: there is a difference between “planning for flexibility” and “I ran out of time, so let’s make this up at the last minute.” Flexibility should flow from what you want your learners to accomplish in the course, not from your lack of planning ahead. In many cases, planning a well-designed, flexible course design could take as much time (or more) as writing out traditional instructor-focused content and activities.

A larger concept to keep in mind is the isolation that can occur to learners in online learning, away from the immediate contact created by being in the same physical location as other learners. Some learners may prefer this distance, while others may feel the effects of the isolation. The idea of “Humanizing” an online course is basically the process or creating ways to connect learners with each other and the instructors across the distance of online learning.

One helpful way to organize and think about humanizing online learning is through the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework (Arbaugh, Bangert, & Cleveland-Innes, 2010). CoI basically focuses on increasing three “presences” to help learners construct personal meaning in learning as well as to collectively confirm mutual understandings: teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence.

Teaching presence is a large portion of what this manual is covering: designing and facilitating a course in ways that clearly communicates how learning will occur, effectively humanizing or increasing the presence of the instructor. Examples would include clearly defining expectations, creating avenues to encourage learner agency, and timely feedback to learners. One good way to make sure this happens is create a schedule for you to communicate with your learners, via email or other methods, and then make sure you stick to that schedule.

Social presence focuses on the learners in the course, helping them to see themselves as an individual “real person” that can actively and safely participate in the course. Many of these concepts are also covered in this manual. Examples would include drawing in participants, creating low-risk ways for them to express themselves, and establishing Codes of Conduct (see the chapter on “Utilizing Social Learning”).

Cognitive presence is a bit more abstract of a concept, but it basically covers looking at the entire learning process for ways to encourage students to think about their learning, reflect on that learning, and sharing their learning process with others. Examples would include encouraging learners to take ownership of their learning, building in reflection activities, and creating avenues for learners to share and interact with those reflections (for instance, by blogging).

For more information on CoI and Humanizing online learning, see these resources:

One possible way to foster teaching presence is to schedule time for synchronous interactive sessions during your course. This could include virtual office hours, live sessions, unhangouts, or other ways for you to connect with your learners virtually “in person.”

The basic idea behind these sessions is that you choose a time to meet, a synchronous service to utilize (usually one that is free to use and allows flexibility to use video and audio if you choose), and set some parameters for what will happen at the session. Will it be a teaching session where learners listen to what you have to share? Will it be a Q&A/Office Hours type of session? Will it be a group work/discussion session where learners interact with each other? Depending on how you want to structure the session, make sure your tool can handle the service you want to utilize.

Virtual Office Hours will typically be a time for learners to ask questions. This will typically involve scheduling a recurring time each week for people to come ask questions online. If you are teaching an online course, we strongly suggest you set virtual office hours. Most online chat or video tools will have a set of options that can handle the “one-on-one office hours” format, but if you want to have more of a group Q&A, you might want to use a tool that can handle multiple users at once. Also consider recording the sessions for those that can’t make it.

Live Sessions can be used for anything, from group discussions to online lecture sessions. If you are intending to broadcast information, you can use a tool that allows learners to watch more than interact (screen sharing is also a good option to make sure is available in the tool you utilize as well). If you want to field questions, be sure the tool you use has an option for that functionality (look for text chat, polling, and other interactive options). Again, consider recording the sessions for those that can’t make it.

Unhangouts are less structured sessions that allow learners to connect with each other as they like. This is more learner-centered that other sessions, but allows for more self-determined learning designs.

Online gaming and virtual reality are two emerging ideas for online interaction. Many have heard of Second Life, which in the past was used for more nuanced online interaction. Tools like Second Life are still around, and are sometimes used in online learning. These tools are not for every course or topic, but if you have a compelling educational idea for using them, you should explore the possibilities.

Some issues to keep in mind:

Some possible tools to use:

Finally, we offer a list of some things that we generally know will not usually work well in most online courses, also known as “pitfalls to avoid”:

Please realize that no course is perfect. You will probably not do everything that works and avoid everything that does not work in every course offering. The ideal is to look at the items on these lists as goals to strive for. For instance, your course is not going to fall apart if two of the videos go over 8 minutes long. We have just learned from experience that forgetting too many of the things that work or doing too many of the things that don’t work will cause more learners to drop out or even complain on social media or course evaluations.

At some point in your course, you are going to run into learners that have some type of problem: they may not understand something, or have gotten behind, or any other common student issues. You should probably decide now how to react to issues. Some instructors tend to take an approach of catching and shaming learners that have issues. You may have read an article or blog post lamenting how many have grandmothers that pass away each semester, or how learners try weird excuses to get out of due dates, or how various life issues bleed into the class. These instructors usually take a very hard line stance that involves not believing learners.

Certainly some learners will lie at some point about something. However, creating an atmosphere that assumes this from the beginning will tend to add more tension than is needed in a course. We would generally encourage you to take a stance that gives learners the benefit of the doubt, showing compassion instead of suspicion.

A lot of this boils down to how you handle course assignments and deadlines. There may be some required assignments or assessments that are given to you by the institution. Others will be under your control. One way to deal with late work and excuses is to look at assignment grading as more of a conversation than a one-time “gotcha!” event. For example, allow learners to turn assignments in for early feedback before deadlines. Create avenues for learners that genuinely get behind to be able to catch up. Ask yourself: Are you more concerned with them learning the content, or learning a calendar?

Of course, many student issues arise from various aspects of grading or assessment in courses. Many people work in institutions or companies that require grades. However, not everyone does, and even many places that require grades leave it up to the instructor on how to calculate those grades.

For several decades, many educators have been questioning the practice of grading (Kohn, 2011; Sackstein, 2015). Sometimes this is because the grades have to include things that have nothing to do with what the learner actually learned. A student that completely understands the concept of a lesson, but runs a few days late can potentially earn the same grade as the person that really doesn’t get the concept but follows all the technical instructions perfectly. Other educators object to how grades are a reflection of how well learners can game the grading system rather than learn the content. Still others object to the unnecessary competition that society creates around the highest grades, and the pressure that puts on learners. There are many reasons to find grades problematic.

But is it possible to have a meaningful class without grades? There are many different ways to look at this. Some instructors will allow learners to create the grading system for the class. Others will allow learners to grade themselves. Still others will abolish grades altogether and replace them with things like badges, certificates, and other forms of alternative certification (see the section on “Certification and Badges” for more information on that). There is a range of responses to the problems that many see with grades. If you are thinking of taking a different path with grading in your course, here are some resources to consider reading:

Whether or not you are going to grade your students, have them grade themselves, or go grade-less in your course, you will still need to take several issues concerning how you design your assessment (or your learners’ self-assessments) into consideration. See the Chapter on “Assessment and Grading Issues” for more details on those considerations.

References

Anderson, T., & Garrison, D. R. (1998). Learning in a networked world: New roles and responsibilities. In C. Gibson (Ed.), Distance learners in higher education (pp. 97-112). Madison, WI.: Atwood Publishing.

Arbaugh, J. B., Bangert, A., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2010). Subject matter effects and the community of inquiry (CoI) framework: An exploratory study. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1), 37-44.

Cercone, K. (2008). Characteristics of adult learners with implications for online learning design. AACE journal, 16(2), 137-159.

DiCarlo, S. E. (2009). Too much content, not enough thinking, and too little FUN! Advances in Physiology Education, 33(4), 257-264.

Dick, W., Carey, L., & Carey, J. O. (2001). The systematic design of instruction (Vol. 5). New York: Longman.

Dron, J. (2007). Control and constraint in e-learning: Choosing when to choose. Hershey, PA: IGI Global. doi:10.4018/978-1-59904-390-6

Groundwater-Smith, S. (2008). Listening to students. The EBE Journal, 2, 18-20.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014, March). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of mooc videos. In Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@ scale conference (pp. 41-50). ACM.

Hayes, S. (2015). MOOCs and Quality: A review of the recent literature. Retrieved from http://eprints.aston.ac.uk/26604/1/MOOCs_and_quality_a_review_of_the_recent_literature.pdf

Hillman, D. C. A., Willis, D. J., & Gunawardena, C. N. (1994). Learner-interface interaction in distance education: An extension of contemporary models and strategies for practitioners. American Journal of Distance Education, 8(2), 30-42.

Jordan, K. (2015). Massive open online course completion rates revisited: Assessment, length and attrition. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(3), 341-358.

Khalil, H., & Ebner, M. (2014, June). MOOCs completion rates and possible methods to improve retention-A literature review. In World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications (No. 1, pp. 1305-1313).

Kohn, A. (2011). The case against grades. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 28-33.