Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a1. Critical Introduction to the Field

2. Theorizing Lived Experiences

3. Identity Terms

4. Conceptualizing Structures of Power

5. Social Constructionism

6. Intersectionality

References: Unit I

7. Introduction: Binary Systems

8. Theorizing Sex/Gender/Sexuality

9. Gender and Sex – Transgender and Intersex

10. Sexualities

11. Masculinities

12. Race

13. Class

14. Alternatives to Binary Systems

References: Unit II

15. Introduction: Institutions, Cultures, and Structures

16. Family

17. Media

18. Medicine, Health, and Reproductive Justice

19. State, Laws, and Prisons

20. Intersecting Institutions Case Study: The Struggle to End Gendered Violence and Violence Against Women

References: Unit III

21. Introduction: Gender, Work and Globalization

22. Gender and Work in the US

23. Gender and the US Welfare State

24. Transnational Production and Globalization

25. Racialized, Gendered, and Sexualized Labor in the Global Economy

References: Unit IV

26. Introduction: Feminist Movements

27. 19th Century Feminist Movements

28. Early to Late 20th Century Feminist Movements

29. Third Wave and Queer Feminist Movements

References: Unit V

Thanks to the Open Education Initiative Grant at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, for providing the funds and support to develop this on-line textbook. It was originally produced for the course, Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies 187: Gender, Sexuality, and Culture, an introductory-level, general education, large-lecture course which has reached upwards of 600 students per academic year. Co-authored by Associate Professor Miliann Kang and graduate teaching assistants Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston and Sonny Nordmarken, this text draws on the collaborative teaching efforts over many years in the department of Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies. Many faculty, staff, teaching assistants and students have developed the course and generously shared teaching materials.

In the past, we have assigned textbooks which cost approximately $75 per book. Many students, including the many non-traditional and working-class students this course attracts, experienced financial hardship in purchasing required texts. In addition, the intersectional and interdisciplinary content of this class is unique and we felt could not be found in any single existing textbook currently on the market. In recent years, we have attempted to utilize e-reserves for assigned course readings. While more accessible, students and faculty agree that this approach tends to lack the structure found in a textbook, as it is difficult for students to complete all assigned readings and they are missing an anchoring reference text. This situation prompted us to begin drafting this text that we would combine with other assigned readings and make available as an open source textbook.

While this textbook draws from and engages with the interdisciplinary field of WGSS, it reflects the disciplinary expertise of the four authors, who are all sociologists. We recognize this as both a strength and weakness of the text, as it provides a strong sociological approach but does not cover the entire range of work in the field.

We would like to continue the practice of having our students access online content available in the University Learning Commons free of charge and hope this resource will be useful to anyone interested in learning more about the rich, vibrant and important field of Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies.

There was a time when it seemed all knowledge was produced by, about, and for men. This was true from the physical and social sciences to the canons of music and literature. Looking from the angle of mainstream education, studies, textbooks, and masterpieces were almost all authored by white men. It was not uncommon for college students to complete entire courses reading only the work of white men in their fields.

Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies (WGSS) is an interdisciplinary field that challenges the androcentric production of knowledge. Androcentrism is the privileging of male- and masculine-centered ways of understanding the world.

Alison Bechdel, a lesbian feminist comics artist, described what has come to be known as “the Bechdel Test,” which demonstrates the androcentric perspective of a majority of feature-length films. Films only pass the Bechdel Test if they 1) Feature two women characters, 2) Those two women characters talk to each other, and 3) They talk to each other about something other than a man. Many people might be surprised to learn that a majority of films do not pass this test! This demonstrates how androcentrism is pervasive in the film industry and results in male-centered films.

Feminist frequency. (2009, December 7). The bechdel test for women in movies. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLF6sAAMb4s .

Feminist scholars argue that the common assumption that knowledge is produced by rational, impartial (male) scientists often obscures the ways that scientists create knowledge through gendered, raced, classed, and sexualized cultural perspectives (e.g., Scott 1991). Feminist scholars include biologists, anthropologists, sociologists, historians, chemists, engineers, economists and researchers from just about any identifiable department at a university. Disciplinary diversity among scholars in this field facilitates communication across the disciplinary boundaries within the academy to more fully understand the social world. This text offers a general introduction to the field of Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies. As all authors of this textbook are trained both as sociologists and interdisciplinary feminist scholars, we situate our framework, which is heavily shaped by a sociological lens, within larger interdisciplinary feminist debates. We highlight some of the key areas in the field rather than comprehensively covering every topic.

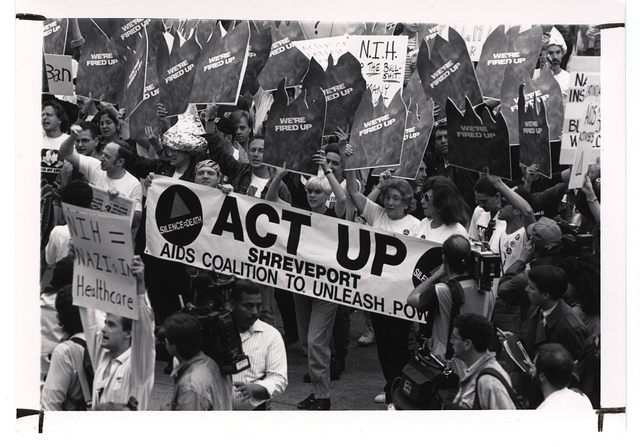

The Women’s Liberation Movement and Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th Century called attention to these conditions and aimed to address these absences in knowledge. Beginning in the 1970s, universities across the United States instituted Women’s and Ethnic Studies departments (African American Studies, Asian American Studies, Latin American Studies, Native American Studies, etc.) in response to student protests and larger social movements. These departments reclaimed buried histories and centered the knowledge production of marginalized groups. As white, middle-class, heterosexual women had the greatest access to education and participation in Women’s Studies, early incarnations of the field stressed their experiences and perspectives. In subsequent decades, studies and contributions of women of color, immigrant women, women from the global south, poor and working class women, and lesbian and queer women became integral to Women’s Studies. More recently, analyses of disability, sexualities, masculinities, religion, science, gender diversity, incarceration, indigeneity, and settler colonialism have become centered in the field. As a result of this opening of the field to incorporate a wider range of experiences and objects of analysis, many Women’s Studies department are now re-naming themselves “Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies” departments.

Feminist scholars recognize the inextricable connection between the notions of gender and sexuality in U.S. society, not only for women but also for men and people of all genders, across a broad expanse of topics. In an introductory course, you can expect to learn about the impact of stringent beauty standards produced in media and advertising, why childrearing by women may not be as natural as we think, the history of the gendered division of labor and its continuing impact on the economic lives of men and women, the unique health issues addressed by advocates of reproductive justice, the connections between women working in factories in the global south and women consuming goods in the United States, how sexual double-standards harm us all, the historical context for feminist movements and where they are today, and much more.

More than a series of topics, Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies offers a way of seeing the world differently. Scholars in this field make connections across institutional contexts (work, family, media, law, the state), value the knowledge that comes from lived experiences, and attend to, rather than ignore, marginalized identities and groups. Thanks to the important critiques of transnational, post-colonial, queer, trans and feminists of color, most contemporary WGSS scholars strive to see the world through the lens of intersectionality. That is, they see systems of oppression working in concert rather than separately. For instance, the way sexism is experienced depends not only on a person’s gender but also on how the person experiences racism, economic inequality, ageism, and other forms of marginalization within particular historical and cultural contexts.

Intersectionality can be challenging to understand. This video explains the intersectionality framework using the example of gender-specific and race-specific anti-discrimination policies that failed to protect Black women.

Can you think of some other contexts in which people who are marginalized in multiple ways might be left out?

What are some things you can do to include them?

Peter Hopkins, Newcastle University. (2018, April 22). What is intersectionality?. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/263719865. Used with permission.

By recognizing the complexity of the social world, Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies advocates for social change and provides insight into how this can be accomplished.

You may have heard the phrase “the personal is political” at some point in your life. This phrase, popularized by feminists in the 1960s, highlights the ways in which our personal experiences are shaped by political, economic, and cultural forces within the context of history, institutions, and culture. Socially-lived theorizing means creating feminist theories and knowledge from the actual day-to-day experiences of groups of people who have traditionally been excluded from the production of academic knowledge. A key element to feminist analysis is a commitment to the creation of knowledge grounded in the experiences of people belonging to marginalized groups, including for example, women, people of color, people in the Global South, immigrants, indigenous people, gay, lesbian, queer, and trans people, poor and working-class people, and disabled people.

Feminist theorists and activists argue for theorizing beginning from the experiences of the marginalized because people with less power and resources often experience the effects of oppressive social systems in ways that members of dominant groups do not. From the “bottom” of a social system, participants have knowledge of the power holders of that system as well as their own experiences, while the reverse is rarely true. Therefore, their experiences allow for a more complete knowledge of the workings of systems of power. For example, a story of the development of industry in the 19th century told from the perspective of the owners of factories would emphasize capital accumulation and industrial progress. However, the development of industry in the 19th century for immigrant workers meant working sixteen-hour days to feed themselves and their families and fighting for employer recognition of trade unions so that they could secure decent wages and the eight-hour work day. Depending on which point-of-view you begin with, you will have very different theories of how industrial capitalism developed, and how it works today.

Feminism is not a single school of thought but encompasses diverse theories and analytical perspectives—such as socialist feminist theories, radical sex feminist theories, black feminist theories, queer feminist theories , transfeminist theories, feminist disability theories, and intersectional feminist theories.

In the video below, “Barbie explains feminist theories,” Cristen, of “Ask Cristen,” defines feminisms generally as a project that works for the “political, social, and economic equality of the sexes,” and suggests that different types of feminist propose different sources of gender inequality and solutions. Cristen (with Barbie’s help) identifies and defines 11 different types of feminism and the solutions they propose:

What types of feminism do Cristen and Barbie leave out of this list? Do you agree with how they characterize these types of feminism? Which issues across these feminisms do you think are most important?

Stuff Mom Never Told You – HowStuffWorks. (2016, March 3). Barbie Explains Feminist Theories | Radical, Liberal, Black, etc. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3D_C-Nes60.

The common thread in all these feminist theories is the belief that knowledge is shaped by the political and social context in which it is made (Scott 1991). Acknowledging that all knowledge is constructed by individuals inhabiting particular social locations, feminist theorists argue that reflexivity—understanding how one’s social position influences the ways that they understand the world—is of utmost necessity when creating theory and knowledge. As people occupy particular social locations in terms of race, class, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, age, and ability, these multiple identities in combination all at the same time shape their social experiences. At certain times, specific dimensions of their identities may be more salient than at others, but at no time is anyone without multiple identities. Thus, categories of identity are intersectional, influencing the experiences that individuals have and the ways they see and understand the world around them.

In the United States, we often are taught to think that people are self-activating, self-actualizing individuals. We repeatedly hear that everyone is unique and that everyone has an equal chance to make something of themselves. While feminists also believe that people have agency—or the ability to influence the direction of their lives—they also argue that an individual’s agency is limited or enhanced by their social position. A powerful way to understand oneself and one’s multiple identities is to situate one’s experiences within multiple levels of analysis—micro – (individual), meso- (group), macro- (structural), and global. These levels of analysis offer different analytical approaches to understanding a social phenomenon. Connecting personal experiences to larger, structural forces of race, gender, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and ability allows for a more powerful understanding of how our own lives are shaped by forces greater than ourselves, and how we might work to change these larger forces of inequality. Like a microscope that is initially set on a view of the most minute parts of a cell, moving back to see the whole of the cell, and then pulling one’s eye away from the microscope to see the whole of the organism, these levels of analysis allow us to situate day-to-day experiences and phenomena within broader, structural processes that shape whole populations. The micro level is that which we, as individuals, live everyday—interacting with other people on the street, in the classroom, or while we are at a party or a social gathering. Therefore, the micro-level is the level of analysis focused on individuals’ experiences. The meso level of analysis moves the microscope back, seeing how groups, communities and organizations structure social life. A meso level-analysis might look at how churches shape gender expectations for women, how schools teach students to become girls and boys, or how workplace policies make gender transition and recognition either easier or harder for trans and gender nonconforming workers. The macro level consists of government policies, programs, and institutions, as well as ideologies and categories of identity. In this way, the macro level involves national power structures as well as cultural ideas about different groups of people according to race, class, gender, and sexuality spread through various national institutions, such as media, education and policy. Finally, the global level of analysis includes transnational production, trade, and migration, global capitalism, and transnational trade and law bodies (such as the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations, the World Trade Organization)—larger transnational forces that bear upon our personal lives but that we often ignore or fail to see.

How Macro Structures Impact People: Maquiladoras

Applying multiple levels of analysis, let’s look at the experiences of a Latina working in a maquiladora, a factory on the border of the US and Mexico. These factories were built to take advantage of the difference in the price of labor in these two countries. At the micro level, we can see the worker’s daily struggles to feed herself and her family. We can see how exhausted she is from working every day for more than eight hours and then coming home to care for herself and her family. Perhaps we could examine how she has developed a persistent cough or skin problems from working with the chemicals in the factory and using water contaminated with run-off from the factory she lives near. On the meso-level, we can see how the community that she lives within has been transformed by the maquiladora, and how other women in her community face similar financial, health, and environmental problems. We may also see how these women are organizing together to attempt to form a union that can press for higher wages and benefits. Moving to the macro and global levels, we can situate these experiences within the Mexican government’s participation within global and regional trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) and the Central American Free Trade Act (CAFTA) and their negative effects on environmental regulations and labor laws, as well as the effects of global capitalist restructuring that has shifted production from North America and Europe to Central and South America and Asia. For further discussion, see the textbook section on globalization.

Recognizing how forces greater than ourselves operate in shaping the successes and failures we typically attribute to individual decisions allows us see how inequalities are patterned by race, class, gender, and sexuality—not just by individual decisions. Approaching these issues through multiple levels of analysis—at the micro, meso, and macro/global levels—gives a more integrative and complete understanding of both personal experience and the ways in which macro structures affect the people who live within them. Through looking at labor in a maquiladora through multiple levels of analysis we are able to connect what are experienced at the micro level as personal problems to macro economic, cultural, and social problems. This not only gives us the ability to develop socially-lived theory, but also allows us to organize with other people who feel similar effects from the same economic, cultural, and social problems in order to challenge and change these problems.

Language is political, hotly contested, always evolving, and deeply personal to each person who chooses the terms with which to identify themselves. To demonstrate respect and awareness of these complexities, it is important to be attentive to language and to honor and use individuals’ self-referential terms (Farinas and Farinas 2015). Below are some common identity terms and their meanings. This discussion is not meant to be definitive or prescriptive but rather aims to highlight the stakes of language and the debates and context surrounding these terms, and to assist in understanding terms that frequently come up in classroom discussions. While there are no strict rules about “correct” or “incorrect” language, these terms reflect much more than personal preferences. They reflect individual and collective histories, ongoing scholarly debates, and current politics.

“People of color” vs. “Colored people”

People of color is a contemporary term used mainly in the United States to refer to all individuals who are non-white (Safire 1988). It is a political, coalitional term, as it encompasses common experiences of racism. People of color is abbreviated as POC. Black or African American are commonly the preferred terms for most individuals of African descent today. These are widely used terms, though sometimes they obscure the specificity of individuals’ histories. Other preferred terms are African diasporic or African descent, to refer, for example, to people who trace their lineage to Africa but migrated through Latin America and the Caribbean. Colored people is an antiquated term used before the civil rights movement in the United States and the United Kingdom to refer pejoratively to individuals of African descent. The term is now taken as a slur, as it represents a time when many forms of institutional racism during the Jim Crow era were legal.

“Disabled people” vs. “People with disabilities”

Some people prefer person-first phrasing, while others prefer identity-first phrasing. People-first language linguistically puts the person before their impairment (physical, sensory or mental difference). Example: “a woman with a vision impairment.” This terminology encourages nondisabled people to think of those with disabilities as people (Logsdon 2016). The acronym PWD stands for “people with disabilities.” Although it aims to humanize, people-first language has been critiqued for aiming to create distance from the impairment, which can be understood as devaluing the impairment. Those who prefer identity-first language often emphasize embracing their impairment as an integral, important, valued aspect of themselves, which they do not want to distance themselves from. Example: “a disabled person.” Using this language points to how society disables individuals (Liebowitz 2015). Many terms in common use have ableist meanings, such as evaluative expressions like “lame,” “retarded,” “crippled,” and “crazy.” It is important to avoid using these terms. Although in the case of disability, both people-first and disability-first phrasing are currently in use, as mentioned above, this is not the case when it comes to race.

“Transgender,” vs. “Transgendered,” “Trans,” “Trans*,” “Non-binary,” “Genderqueer,” “Genderfluid,” “Agender,” “Transsexual,” “Cisgender,” “Cis”

Transgender generally refers to individuals who identify as a gender not assigned to them at birth. The term is used as an adjective (i.e., “a transgender woman,” not “a transgender”), however some individuals describe themselves by using transgender as a noun. The term transgendered is not preferred because it emphasizes ascription and undermines self-definition. Trans is an abbreviated term and individuals appear to use it self-referentially these days more often than transgender. Transition is both internal and social. Some individuals who transition do not experience a change in their gender identity since they have always identified in the way that they do. Trans* is an all-inclusive umbrella term which encompasses all nonnormative gender identities (Tompkins 2014). Non-binary and genderqueer refer to gender identities beyond binary identifications of man or woman. The term genderqueer became popularized within queer and trans communities in the 1990s and 2000s, and the term non-binary became popularized in the 2010s (Roxie 2011). Agender, meaning “without gender,” can describe people who do not have a gender identity, while others identify as non-binary or gender neutral, have an undefinable identity, or feel indifferent about gender (Brooks 2014). Genderfluid people experience shifts between gender identities. The term transsexual is a medicalized term, and indicates a binary understanding of gender and an individual’s identification with the “opposite” gender from the gender assigned to them at birth. Cisgender or cis refers to individuals who identify with the gender assigned to them at birth. Some people prefer the term non-trans. Additional gender identity terms exist; these are just a few basic and commonly used terms. Again, the emphasis of these terms is on viewing individuals as they view themselves and using their self-designated names and pronouns.

“Queer,” “Bisexual,” “Pansexual,” “Polyamorous,” “Asexual,”

Queer as an identity term refers to a non-categorical sexual identity; it is also used as a catch-all term for all LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) individuals. The term was historically used in a derogatory way, but was reclaimed as a self-referential term in the 1990s United States. Although many individuals identify as queer today, some still feel personally insulted by it and disapprove of its use. Bisexual is typically defined as a sexual orientation marked by attraction to either men or women. This has been problematized as a binary approach to sexuality, which excludes individuals who do not identify as men or women. Pansexual is a sexual identity marked by sexual attraction to people of any gender or sexuality. Polyamorous (poly, for short) or non-monogamous relationships are open or non-exclusive; individuals may have multiple consensual and individually-negotiated sexual and/or romantic relationships at once (Klesse 2006). Asexual is an identity marked by a lack of or rare sexual attraction, or low or absent interest in sexual activity, abbreviated to “ace” (Decker 2014). Asexuals distinguish between sexual and romantic attraction, delineating various sub-identities included under an ace umbrella. In several later sections of this book, we discuss the terms heteronormativity, homonormativity, and homonationalism; these terms are not self-referential identity descriptors but are used to describe how sexuality is constructed in society and the politics around such constructions.

“Latino,” “Latin American,” “Latina,” “Latino/a,” “Latin@,” “Latinx,” “Chicano,” “Xicano,” “Chicana,” “Chicano/a,” “Chican@,” “Chicanx,” “Mexican American,” “Hispanic”

Latino is a term used to describe people of Latin American origin or descent in the United States, while Latin American describes people in Latin America. Latino can refer specifically to a man of Latin American origin or descent; Latina refers specifically to a woman of Latin American origin or descent. The terms Latino/a and Latin@ include both the –o and –a endings to avoid the sexist use of “Latino” to refer to all individuals. Chicano, Chicano/a, and Chican@ similarly describe people of Mexican origin or descent in the United States, and may be used interchangeably with Mexican American, Xicano or Xicano/a. However, as Chicano has the connotation of being politically active in working to end oppression of Mexican Americans, and is associated with the Chicano literary and civil rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s, people may prefer the use of either Chicano or Mexican American, depending on their political orientation. Xicano is a shortened form of Mexicano, from the Nahuatl name for the indigenous Mexica Aztec Empire. Some individuals prefer the Xicano spelling to emphasize their indigenous ancestry (Revilla 2004). Latinx and Chicanx avoid either the –a or the –o gendered endings to explicitly include individuals of all genders (Ramirez and Blay 2017). Hispanic refers to the people and nations with a historical link to Spain and to people of country heritage who speak the Spanish language. Although many people can be considered both Latinx and Hispanic, Brazilians, for example, are Latin American but neither Hispanic nor Latino, while Spaniards are Hispanic but not Latino. Preferred terms vary regionally and politically; these terms came into use in the context of the Anglophone-dominated United States.

“Indigenous,” “First Nations,” “Indian,” “Native,” “Native American,” “American Indian,” “Aboriginal”

Indigenous refers to descendants of the original inhabitants of an area, in contrast to those that have settled, occupied or colonized the area (Turner 2006). Terms vary by specificity; for example, in Australia, individuals are Aboriginal, while those in Canada are First Nations. “Aboriginal” is sometimes used in the Canadian context, too, though more commonly in settler-government documents, not so much as a term of self-definition. In the United States, individuals may refer to themselves as Indian, American Indian, Native, or Native American, or, perhaps more commonly, they may refer to their specific tribes or nations. Because of the history of the term, “Indian,” like other reclaimed terms, outsiders should be very careful in using it.

“Global South,” “Global North,” “Third world,” “First world,” “Developing country,” “Developed country”

Global South and Global North refer to socioeconomic and political divides. Areas of the Global South, which are typically socioeconomically and politically disadvantaged are Africa, Latin America, parts of Asia, and the Middle East. Generally, Global North areas, including the United States, Canada, Western Europe and parts of East Asia, are typically socioeconomically and politically advantaged. Terms like Third world, First world, Developing country, and Developed country have been problematized for their hierarchical meanings, where areas with more resources and political power are valued over those with less resources and less power (Silver 2015). Although the terms Global South and Global North carry the same problematic connotations, these tend to be the preferred terms today. In addition, although the term Third world has been problematized, some people do not see Third world as a negative term and use it self-referentially. Also, Third world was historically used as an oppositional and coalitional term for nations and groups who were non-aligned with either the capitalist First world and communist Second world especially during the Cold War. For example, those who participated in the Third World Liberation Strike at San Francisco State University from 1968 to 1969 used the term to express solidarity and to establish Black Studies and the Ethnic Studies College (Springer 2008). We use certain terms, like Global North/South, throughout the book, with the understanding that there are problematic aspects of these usages.

“Transnational,” “Diasporic,” “Global,” “Globalization”

Transnational has been variously defined. Transnational describes migration and the transcendence of borders, signals the diminishing relevance of the nation-state in the current iteration of globalization, is used interchangeably with diasporic (any reference to materials from a region outside its current location), designates a form of neocolonialism (e.g., transnational capital) and signals the NGOization of social movements. For Inderpal Grewal and Caren Kaplan (2001), the terms “transnational women’s movements” or “global women’s movements” are used to refer to U.N. conferences on women, global feminism as a policy and activist arena, and human rights initiatives that enact new forms of governmentality. Chandra Mohanty (2003) has argued that transnational feminist scholarship and social movements critique and mobilize against globalization, capitalism, neoliberalism, neocolonialism, and non-national institutions like the World Trade Organization. In this sense, transnational refers to “cross-national solidarity” in feminist organizing. Grewal and Caplan (2001) have observed that transnational feminist inquiry also examines how these movements have been tied to colonial processes and imperialism, as national and international histories shape transnational social movements. In feminist politics and studies, the term transnational is used much more than “international,” which has been critiqued because it centers the nation-state. Whereas transnational can also take seriously the role of the state it does not assume that the state is the most relevant actor in global processes. Although all of these are technically global processes, the term “global” is oftentimes seen as abstract. It appeals to the notion of “global sisterhood,” which is often suspect because of the assumption of commonalities among women that often times do not exist.

A social structure is a set of long-lasting social relationships, practices and institutions that can be difficult to see at work in our daily lives. They are intangible social relations, but work much in the same way as structures we can see: buildings and skeletal systems are two examples. The human body is structured by bones; that is to say that the rest of our bodies’ organs and vessels are where they are because bones provide the structure upon which these other things can reside. Structures limit possibility, but they are not fundamentally unchangeable. For instance, our bones may deteriorate over time, suffer acute injuries, or be affected by disease, but they never spontaneously change location or disappear into thin air. Such is the way with social structures.

The elements of a social structure, the parts of social life that direct possible actions, are the institutions of society. These will be addressed in more detail later, but for now social institutions may be understood to include: the government, work, education, family, law, media, and medicine, among others. To say these institutions direct, or structure, possible social action, means that within the confines of these spaces there are rules, norms, and procedures that limit what actions are possible. For instance, family is a concept near and dear to most, but historically and culturally family forms have been highly specified, that is structured. According to Dorothy Smith (1993), the standard North American family (or, SNAF) includes two heterosexually-married parents and one or more biologically-related children. It also includes a division of labor in which the husband/father earns a larger income and the wife/mother takes responsibility for most of the care-taking and childrearing. Although families vary in all sorts of ways, this is the norm to which they are most often compared. Thus, while we may consider our pets, friends, and lovers as family, the state, the legal system, and the media do not affirm these possibilities in the way they affirm the SNAF. In turn, when most people think of who is in their family, the normative notion of parents and children structures who they consider.

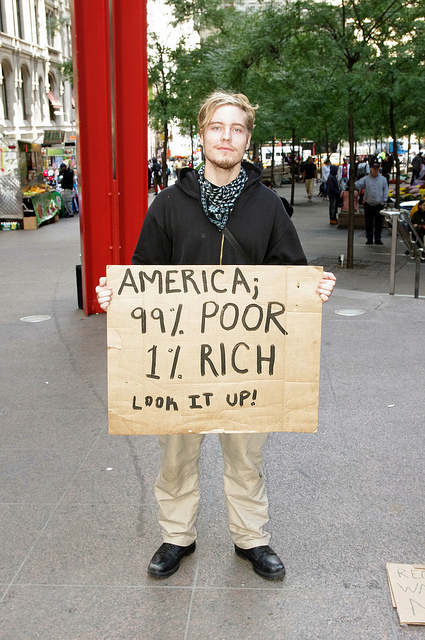

Overlaying these social structures are structures of power. By power we mean two things: 1) access to and through the various social institutions mentioned above, and 2) processes of privileging, normalizing, and valuing certain identities over others. This definition of power highlights the structural, institutional nature of power, while also highlighting the ways in which culture works in the creation and privileging of certain categories of people. Power in American society is organized along the axes of gender, race, class, sexuality, ability, age, nation, and religious identities. Some identities are more highly valued, or more normalized, than others—typically because they are contrasted to identities thought to be less valuable or less “normal.” Thus, identities are not only descriptors of individuals, but grant a certain amount of collective access to the institutions of social life. This is not to say, for instance, that all white people are alike and wield the same amount of power over all people of color. It does mean that white, middle-class women as a group tend to hold more social power than middle-class women of color. This is where the concept of intersectionality is key. All individuals have multiple aspects of identity, and simultaneously experience some privileges due to their socially valued identity statuses and disadvantages due to their devalued identity statuses. Thus a white, heterosexual middle-class woman may be disadvantaged compared to a white middle-class man, but she may experience advantages in different contexts in relation to a black, heterosexual middle-class woman, or a white, heterosexual working-class man, or a white lesbian upper-class woman.

At the higher level of social structure, we can see that some people have greater access to resources and institutionalized power across the board than do others. Sexism is the term we use for discrimination and blocked access women face. Genderism describes discrimination and blocked access that transgender people face. Racism describes discrimination and blocked access on the basis of race, which is based on socially-constructed meanings rather than biological differences. Classism describes discrimination on the basis of social class, or blocked access to material wealth and social status. Ableism describes discrimination on the basis of physical, mental, or emotional impairment or blocked access to the fulfillment of needs and in particular, full participation in social life. These “-isms” reflect dominant cultural notions that women, trans people, people of color, poor people, and disabled people are inferior to men, non-trans people, white people, middle- and upper-class people, and non-disabled people. Yet, the “-isms” are greater than individuals’ prejudice against women, trans people, people of color, the poor, and disabled people. For instance, in the founding of the United States the institutions of social life, including work, law, education, and the like, were built to benefit wealthy, white men since at the time these were, by law, the only real “citizens” of the country. Although these institutions have significantly changed over time in response to social movements and more progressive cultural shifts, their sexist, genderist, racist, classist, and ableist structures continue to persist in different forms today. Similar-sounding to “-isms,” the language of “-ization,” such as in “racialization” is used to highlight the formation or processes by which these forms of difference have been given meaning and power (Omi and Winant 1986). (See further discussion on this process in the section below on social construction).

Just like the human body’s skeletal structure, social structures are not immutable, or completely resistant to change. Social movements mobilized on the basis of identities have fought for increased equality and changed the structures of society, in the US and abroad, over time. However, these struggles do not change society overnight; some struggles last decades, centuries, or remain always unfinished. The structures and institutions of social life change slowly, but they can and do change based on the concerted efforts of individuals, social movements and social institutions.

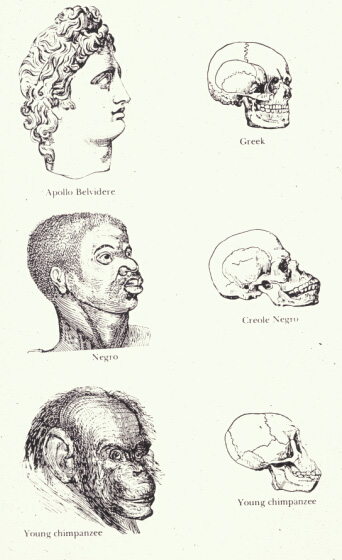

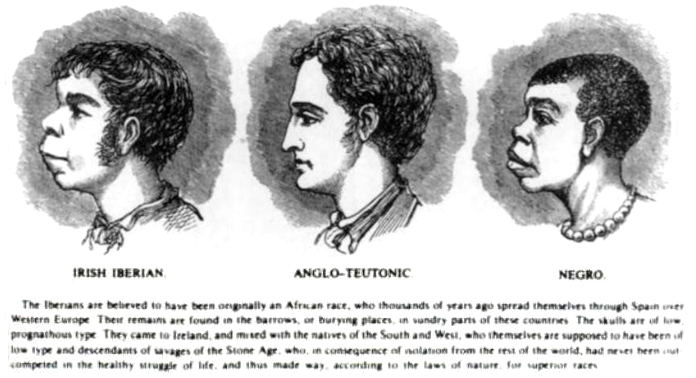

Social constructionism is a theory of knowledge that holds that characteristics typically thought to be immutable and solely biological—such as gender, race, class, ability, and sexuality—are products of human definition and interpretation shaped by cultural and historical contexts (Subramaniam 2010). As such, social constructionism highlights the ways in which cultural categories—like “men,” “women,” “black,” “white”—are concepts created, changed, and reproduced through historical processes within institutions and culture. We do not mean to say that bodily variation among individuals does not exist, but that we construct categories based on certain bodily features, we attach meanings to these categories, and then we place people into the categories by considering their bodies or bodily aspects. For example, by the one-drop rule (see also page 35), regardless of their appearance, individuals with any African ancestor are considered black. In contrast, racial conceptualization and thus racial categories are different in Brazil, where many individuals with African ancestry are considered to be white. This shows how identity categories are not based on strict biological characteristics, but on the social perceptions and meanings that are assumed. Categories are not “natural” or fixed and the boundaries around them are always shifting—they are contested and redefined in different historical periods and across different societies. Therefore , the social constructionist perspective is concerned with the meaning created through defining and categorizing groups of people, experience, and reality in cultural contexts.

The Social Construction of Heterosexuality

What does it mean to be “heterosexual” in contemporary US society? Did it mean the same thing in the late 19th century? As historian of human sexuality Jonathon Ned Katz shows in The Invention of Heterosexuality (1999), the word “heterosexual” was originally coined by Dr. James Kiernan in 1892, but its meaning and usage differed drastically from contemporary understandings of the term. Kiernan thought of “hetero-sexuals” as not defined by their attraction to the opposite sex, but by their “inclinations to both sexes.” Furthermore, Kiernan thought of the heterosexual as someone who “betrayed inclinations to ‘abnormal methods of gratification’” (Katz 1995). In other words, heterosexuals were those who were attracted to both sexes and engaged in sex for pleasure, not for reproduction. Katz further points out that this definition of the heterosexual lasted within middle-class cultures in the United States until the 1920s, and then went through various radical reformulations up to the current usage.

Looking at this historical example makes visible the process of the social construction of heterosexuality. First of all, the example shows how social construction occurs within institutions—in this case, a medical doctor created a new category to describe a particular type of sexuality, based on existing medical knowledge at the time. “Hetero-sexuality” was initially a medical term that defined a deviant type of sexuality. Second, by seeing how Kiernan—and middle class culture, more broadly—defined “hetero-sexuality” in the 19th century, it is possible to see how drastically the meanings of the concept have changed over time. Typically, in the United States in contemporary usage, “heterosexuality” is thought to mean “normal” or “good”—it is usually the invisible term defined by what is thought to be its opposite, homosexuality. However, in its initial usage, “hetero-sexuality” was thought to counter the norm of reproductive sexuality and be, therefore, deviant. This gets to the third aspect of social constructionism. That is, cultural and historical contexts shape our definition and understanding of concepts. In this case, the norm of reproductive sexuality—having sex not for pleasure, but to have children—defines what types of sexuality are regarded as “normal” or “deviant.” Fourth, this case illustrates how categorization shapes human experience, behavior, and interpretation of reality. To be a “heterosexual” in middle class culture in the US in the early 1900s was not something desirable to be—it was not an identity that most people would have wanted to inhabit. The very definition of “hetero-sexual” as deviant, because it violated reproductive sexuality, defined “proper” sexual behavior as that which was reproductive and not pleasure-centered.

Social constructionist approaches to understanding the world challenge the essentialist or biological determinist understandings that typically underpin the “common sense” ways in which we think about race, gender, and sexuality. Essentialism is the idea that the characteristics of persons or groups are significantly influenced by biological factors, and are therefore largely similar in all human cultures and historical periods. A key assumption of essentialism is that “a given truth is a necessary natural part of the individual and object in question” (Gordon and Abbott 2002). In other words, an essentialist understanding of sexuality would argue that not only do all people have a sexual orientation, but that an individual’s sexual orientation does not vary across time or place. In this example, “sexual orientation” is a given “truth” to individuals—it is thought to be inherent, biologically determined, and essential to their being.

Essentialism typically relies on a biological determinist theory of identity. Biological determinism can be defined as a general theory, which holds that a group’s biological or genetic makeup shapes its social, political, and economic destiny (Subramaniam 2014). For example, “sex” is typically thought to be a biological “fact,” where bodies are classified into two categories, male and female. Bodies in these categories are assumed to have “sex”-distinct chromosomes, reproductive systems, hormones, and sex characteristics. However, “sex” has been defined in many different ways, depending on the context within which it is defined. For example, feminist law professor Julie Greenberg (2002) writes that in the late 19th century and early 20th century, “when reproductive function was considered one of a woman’s essential characteristics, the medical community decided that the presence or absence of ovaries was the ultimate criterion of sex” (Greenberg 2002: 113). Thus, sexual difference was produced through the heteronormative assumption that women are defined by their ability to have children. Instead of assigning sex based on the presence or absence of ovaries, medical practitioners in the contemporary US typically assign sex based on the appearance of genitalia.

Differential definitions of sex point to two other primary aspects of the social construction of reality. First, it makes apparent how even the things commonly thought to be “natural” or “essential” in the world are socially constructed. Understandings of “nature” change through history and across place according to systems of human knowledge. Second, the social construction of difference occurs within relations of power and privilege. Sociologist Abby Ferber (2009) argues that these two aspects of the social construction of difference cannot be separated, but must be understood together. Discussing the construction of racial difference, she argues that inequality and oppression actually produce ideas of essential racial difference. Therefore, racial categories that are thought to be “natural” or “essential” are created within the context of racialized power relations—in the case of African-Americans, that includes slavery, laws regulating interracial sexual relationships, lynching, and white supremacist discourse. Social constructionist analyses seek to better understand the processes through which racialized, gendered, or sexualized differentiations occur, in order to untangle the power relations within them.

Notions of disability are similarly socially constructed within the context of ableist power relations. The medical model of disability frames body and mind differences and perceived challenges as flaws that need fixing at the individual level. The social model of disability shifts the focus to the disabling aspects of society for individuals with impairments (physical, sensory or mental differences), where the society disables those with impairments (Shakespeare 2006). Disability, then, refers to a form of oppression where individuals understood as having impairments are imagined to be inferior to those without impairments, and impairments are devalued and unwanted. This perspective manifests in structural arrangements that limit access for those with impairments. A critical disability perspective critiques the idea that nondisability is natural and normal—an ableist sentiment, which frames the person rather than the society as the problem.

What are the implications of a social constructionist approach to understanding the world? Because social constructionist analyses examine categories of difference as fluid, dynamic, and changing according to historical and geographical context, a social constructionist perspective suggests that existing inequalities are neither inevitable nor immutable. This perspective is especially useful for the activist and emancipatory aims of feminist movements and theories. By centering the processes through which inequality and power relations produce racialized, sexualized, and gendered difference, social constructionist analyses challenge the pathologization of minorities who have been thought to be essentially or inherently inferior to privileged groups. Additionally, social constructionist analyses destabilize the categories that organize people into hierarchically ordered groups through uncovering the historical, cultural, and/or institutional origins of the groups under study. In this way, social constructionist analyses challenge the categorical underpinnings of inequalities by revealing their production and reproduction through unequal systems of knowledge and power.

Articulated by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991), the concept of intersectionality identifies a mode of analysis integral to women, gender, sexuality studies. Within intersectional frameworks, race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are considered mutually constitutive; that is, people experience these multiple aspects of identity simultaneously and the meanings of different aspects of identity are shaped by one another. In other words, notions of gender and the way a person’s gender is interpreted by others are always impacted by notions of race and the way that person’s race is interpreted. For example, a person is never received as just a woman, but how that person is racialized impacts how the person is received as a woman. So, notions of blackness, brownness, and whiteness always influence gendered experience, and there is no experience of gender that is outside of an experience of race. In addition to race, gendered experience is also shaped by age, sexuality, class, and ability; likewise, the experience of race is impacted by gender, age, class, sexuality, and ability.

Understanding intersectionality requires a particular way of thinking. It is different than how many people imagine identities operate. An intersectional analysis of identity is distinct from single-determinant identity models and additive models of identity. A single determinant model of identity presumes that one aspect of identity, say, gender, dictates one’s access to or disenfranchisement from power. An example of this idea is the concept of “global sisterhood,” or the idea that all women across the globe share some basic common political interests, concerns, and needs (Morgan 1996). If women in different locations did share common interests, it would make sense for them to unite on the basis of gender to fight for social changes on a global scale. Unfortunately, if the analysis of social problems stops at gender, what is missed is an attention to how various cultural contexts shaped by race, religion, and access to resources may actually place some women’s needs at cross-purposes to other women’s needs. Therefore, this approach obscures the fact that women in different social and geographic locations face different problems. Although many white, middle-class women activists of the mid-20th century US fought for freedom to work and legal parity with men, this was not the major problem for women of color or working-class white women who had already been actively participating in the US labor market as domestic workers, factory workers, and slave laborers since early US colonial settlement. Campaigns for women’s equal legal rights and access to the labor market at the international level are shaped by the experience and concerns of white American women, while women of the global south, in particular, may have more pressing concerns: access to clean water, access to adequate health care, and safety from the physical and psychological harms of living in tyrannical, war-torn, or economically impoverished nations.

In contrast to the single-determinant identity model, the additive model of identity simply adds together privileged and disadvantaged identities for a slightly more complex picture. For instance, a Black man may experience some advantages based on his gender, but has limited access to power based on his race. This kind of analysis is exemplified in how race and gender wage gaps are portrayed in statistical studies and popular news reports. Below, you can see a median wage gap table from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research compiled in 2009. In reading the table, it can be seen that the gender wage gap is such that in 2009, overall, women earned 77% of what men did in the US. The table breaks down the information further to show that earnings varied not only by gender but by race as well. Thus, Hispanic or Latino women earned only 52.9% of what white men did while white women made 75%. This is certainly more descriptive than a single gender wage gap figure or a single race wage gap figure. The table is useful at pointing to potential structural explanations that may make earnings differ between groups. For instance, looking at the chart, you may immediately wonder why these gaps exist; is it a general difference of education levels, occupations, regions of residence or skill levels between groups, or is it something else, such as discrimination in hiring and promotion? What it is not useful for is predicting people’s incomes by plugging in their gender plus their race, even though it may be our instinct to do so. Individual experiences differ vastly and for a variety of reasons; there are outliers in every group. Most importantly, even if this chart helps in understanding structural reasons why incomes differ, it doesn’t provide all the answers.

Table 1: Average Annual Earnings for Year-Round Full-Time Workers age 15 Years and Older by Race and Ethnicity, 2015

| Racial/Ethnic Background* | Men ($) | Women ($) | Women’s Earnings as % of White Male Earnings |

| All Racial/Ethnic Groups | 51,212 | 40,742 | – |

| White | 57,204 | 43,063 | 75.3% |

| Black | 41,094 | 36,212 | 63.3% |

| Asian American | 61,672 | 48,313 | 84.5% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 35,673 | 31,109 | 54.4% |

| *White alone, not Hispanic; Black alone or in combination (may include Hispanic); Asian American alone or in combination (may include Hispanic); and Hispanic/Latina/o (may be of any race). Source: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Compilation of U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey. 2016. “Historical Income Tables: Table P-38. Full-Time, Year Round Workers by Median Earnings and Sex: 1987 to 2015. <https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/incomepoverty/historical-income-people.html> | |||

The additive model does not take into account how our shared cultural ideas of gender are racialized and our ideas of race are gendered and that these ideas structure access to resources and power—material, political, interpersonal. Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (2005) has developed a strong intersectional framework through her discussion of race, gender, and sexuality in her historical analysis of representations of Black sexuality in the US. Hill Collins shows how contemporary white American culture exoticizes Black men and women and she points to a history of enslavement and treatment as chattel as the origin and motivator for the use of these images. In order to justify slavery, African-Americans were thought of and treated as less than human. Sexual reproduction was often forced among slaves for the financial benefit of plantation owners, but owners reframed this coercion and rape as evidence of the “natural” and uncontrollable sexuality of people from the African continent. Images of Black men and women were not completely the same, as Black men were constructed as hypersexual “bucks” with little interest in continued relationships whereas Black women were framed as hypersexual “Jezebels” that became the “matriarchs” of their families. Again, it is important to note how the context, where enslaved families were often forcefully dismantled, is often left unacknowledged and contemporary racialized constructions are assumed and framed as individual choices or traits. It is shockingly easy to see how these images are still present in contemporary media, culture, and politics, for instance, in discussions of American welfare programs. This analysis reveals how race, gender, and sexuality intersect. We cannot simply pull these identities apart because they are interconnected and mutually enforcing.

Although the framework of intersectional has contributed important insights to feminist analyses, there are problems. Intersectionality refers to the mutually co-constitutive nature of multiple aspects of identity, yet in practice this term is typically used to signify the specific difference of “women of color,” which effectively produces women of color (and in particular, Black women) as Other and again centers white women (Puar 2012). In addition, the framework of intersectionality was created in the context of the United States; therefore, the use of the framework reproduces the United States as the dominant site of feminist inquiry and women’s studies’ Euro-American bias (Puar 2012). Another failing of intersectionality is its premise of fixed categories of identity, where descriptors like race, gender, class, and sexuality are assumed to be stable. In contrast, the notion of assemblage considers categories events, actions, and encounters between bodies, rather than simply attributes (Puar 2012). Assemblage refers to a collage or collection of things, or the act of assembling. An assemblage perspective emphasizes how relations, patterns, and connections between concepts give concepts meaning (Puar 2012). Although assemblage has been framed against intersectionality, identity categories’ mutual co-constitution is accounted for in both intersectionality and assemblage.

“Gender” is too often used simply and erroneously to mean “white women,” while “race” too often connotes “Black men.” An intersectional perspective examines how identities are related to each other in our own experiences and how the social structures of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability intersect for everyone. As opposed to single-determinant and additive models of identity, an intersectional approach develops a more sophisticated understanding of the world and how individuals in differently situated social groups experience differential access to both material and symbolic resources.

Brooks, Katherine. 2014. “Profound Portraits Of Young Agender Individuals Challenge The Male/Female Identity.” The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/06/03/chloe-aftel-agender_n_5433867.html. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé W. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43(6): 1241–1299.

Decker, Julie Sondra. 2014. The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality. Carrel Books.

Farinas, Caley and Creigh Farinas. 2015. “5 Reasons Why We Police Disabled People’s Language (And Why We Need to Stop)” Everyday Feminism Magazine. http://everydayfeminism.com/2015/07/policing-disabled-peoples-identity/. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Ferber, A. 2009. “Keeping Sex in Bounds: Sexuality and the (De)Construction of Race and Gender.” Pp. 136-142 in Sex, Gender, and Sexuality: The New Basics, edited by Abby L. Ferber, Kimberly Holcomb and Tre Wentling. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Gordon, L. E. and S. A. Abbott. 2002 “A Social Constructionist Essential Guide to Sex.” In Robert Heasley and Betsy Crane, Eds., Sexual Lives: Theories and Realities of Human Sexualities. New York, McGraw-Hill.

Greenberg, J. 2002. “Definitional Dilemmas: Male or Female? Black or White? The Law’s Failure, to Recognize Intersexuals and Multiracials.” Pp.102-126 in Gender Nonconformity, Race and Sexuality: Charting the Connections, edited by T. Lester. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Grewal, Inderpal and Caren Kaplan. 2001. “Global Identities: Theorizing Transnational Studies of Sexuality,” GLQ 7(4): 663-679.

Hesse-Biber, S.N. and D. Leckenby. 2004. “How Feminists Practice Social Research.” Pp. 209-226 in Feminist Perspectives on Social Research. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hill Collins, Patricia. 2005. Black Sexual Politics: African-Americans, Gender, and the New Racism. New York: Routledge.

Institute for Women’s Policy Research Compilation of U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. 2016. “Historical Income Tables: Table P-38. Full-Time, Year Round Workers by Median Earnings and Sex: 1987 to 2015. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/incomepoverty/historical-income-people.html. Accessed 30 March, 2017.

Katz, J. N. 1995. The Invention of Heterosexuality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Klesse, Christian. 2006. “Polyamory and its ‘others’: Contesting the terms of non- monogamy.” Sexualities, 9(5): 565-583.

Liebowitz, Cara. 2015. “I am Disabled: On Identity-First Versus People-First Language.” The Body is Not an Apology. https://thebodyisnotanapology.com/magazine/i-am-disabled-on-identity-first-versus-people-first-language/. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Logsdon, Ann. 2016. “Use Person First Language to Describe People With Disabilities.” Very Well. https://www.verywell.com/focus-on-the-person-first-is-good-etiquette-2161897. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Mohanty, Chandra. 2003. “’Under Western Eyes’ Revisited: Feminist Solidarity Through Anticapitalist Struggles,” Signs 28(2): 499-535.

Morgan, Robin. 1996. “Introduction – Planetary Feminism: The Politics of the 21st Century.” Pp. 1-37 in Sisterhood is Global: The International Women’s Movement Anthology, edited by Morgan. New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY.

Omi, Michael and Howard Winant. 1986. Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. Psychology Press.

Puar, Jasbir K. 2012. “’I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess’: Becoming-Intersectional in Assemblage Theory.” PhiloSOPHIA, 2(1): 49-66.

Ramirez, Tanisha Love and Zeba Blay. 2017. “Why People Are Using the Term ‘Latinx.’” The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/why-people-are-using-the-term-latinx_us_57753328e4b0cc0fa136a159. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Revilla, Anita Tijerina. 2004. “Muxerista Pedagogy: Raza Womyn Teaching Social Justice Through Student Activism.” The High School Journal, 87(4): 87-88.

Roxie, Marilyn. 2011. “Genderqueer and Nonbinary Identities.” http://genderqueerid.com/gqhistory. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Safire, William. 1988. “On Language; People of Color.” The New York Times Magazine. http://www.nytimes.com/1988/11/20/magazine/on-language-people-of-color.html. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Shakespeare, Tom. 2006. “The Social Model of Disability.” In The Disability Studies Reader, ed. Lennard Davis (New York: Routledge, 2d ed.), 197–204.

Silver, Marc. 2015. “If You Shouldn’t Call It The Third World, What Should You Call It?” Goats and Soda, New England Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2015/01/04/372684438/if-you-shouldnt-call-it-the-third-world-what-should-you-call-it. Accessed 15 May, 2017.

Smith, Dorothy. 1993. “The Standard North American Family: SNAF as an Ideological Code.” Journal of Family Issues 14 (1): 50-65.

Subramaniam, Banu. 2014. Ghost Stories for Darwin: The Science of Variation and the Politics of Diversity. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Tompkins, Avery. 2014. “Asterisk.” Transgender Studies Quarterly 1(1-2): 26-27.

Turner, Dale Antony. 2006. This is not a peace pipe: Towards a critical indigenous philosophy. University of Toronto Press.

Black and white. Masculine and feminine. Rich and poor. Straight and gay. Able-bodied and disabled. Binaries are social constructs composed of two parts that are framed as absolute and unchanging opposites. Binary systems reflect the integration of these oppositional ideas into our culture. This results in an exaggeration of differences between social groups until they seem to have nothing in common. An example of this is the phrase “men are from Mars, women are from Venus.” Ideas of men and women being complete opposites invite simplistic comparisons that rely on stereotypes: men are practical, women are emotional; men are strong, women are weak; men lead, women support. Binary notions mask the complicated realities and variety in the realm of social identity. They also erase the existence of individuals, such as multiracial or mixed-race people and people with non-binary gender identities, who may identify with neither of the assumed categories or with multiple categories. We know very well that men have emotions and that women have physical strength, but a binary perspective of gender prefigures men and women to have nothing in common. They are defined against each other; men are defined, in part, as “not women” and women as “not men.” Thus, our understandings of men are influenced by our understandings of women. Rather than seeing aspects of identity like race, gender, class, ability, and sexuality as containing only two dichotomous, opposing categories, conceptualizing multiple various identities allows us to examine how men and women, Black and white, etc., may not be so completely different after all, and how varied and complex identities and lives can be.

The phrase “sex/gender system,” or “sex/gender/sexuality system” was coined by Gayle Rubin (1984) to describe, “the set of arrangements by which a society transforms biological sexuality into products of human activity.” That is, Rubin proposed that the links between biological sex, social gender, and sexual attraction are products of culture. Gender is, in this case, “the social product” that we attach to notions of biological sex. In our heteronormative culture, everyone is assumed to be heterosexual (attracted to men if you are a woman; attracted to women if you are a man) until stated otherwise. People make assumptions about how others should act in social life, and to whom they should be attracted, based on their perceptions of outward bodily appearance, which is assumed to represent biological sex characteristics (chromosomes, hormones, secondary sex characteristics and genitalia). Rubin questioned the biological determinist argument that suggested all people assigned female at birth will identify as women and be attracted to men. According to a biological determinist view, where “biology is destiny,” this is the way nature intended. However, this view fails to account for human intervention. As human beings, we have an impact on the social arrangements of society. Social constructionists believe that many things we typically leave unquestioned as conventional ways of life actually reflect historically- and culturally-rooted power relationships between groups of people, which are reproduced in part through socialization processes, where we learn conventional ways of thinking and behaving from our families and communities. Just because female-assigned people bear children does not necessarily mean that they are always by definition the best caretakers of those children or that they have “natural instincts” that male-assigned people lack.

For instance, the arrangement of women caring for children has a historical legacy (which we will discuss more in the section on gendered labor markets). We see not only mothers but other women too caring for children: daycare workers, nannies, elementary school teachers, and babysitters. What these jobs have in common is that they are all very female-dominated occupations AND that this work is economically undervalued. These people do not get paid very well. One study found that, in New York City, parking lot attendants, on average, make more money than childcare workers (Clawson and Gerstel, 2002). Because “mothering” is not seen as work, but as a woman’s “natural” behavior, she is not compensated in a way that reflects how difficult the work is. If you have ever babysat for a full day, go ahead and multiply that by eighteen years and then try to make the argument that it is not work. Men can do this work just as well as women, but there are no similar cultural dictates that say they should. On top of that, some suggest that if paid caretakers were mostly men, then they would make much more money. In fact, men working in female-dominated occupations actually earn more and gain promotions faster than women. This phenomenon is referred to as the glass escalator. This example illustrates how, as social constructionist Abby Ferber (2009) argues, social systems produce differences between men and women, and not the reverse.

A binary gender perspective assumes that only men and women exist, obscuring gender diversity and erasing the existence of people who do not identify as men or women. A gendered assumption in our culture is that someone assigned female at birth will identify as a woman and that all women were assigned female at birth. While this is true for cisgender (or “cis”) individuals—people who identify in accordance with their gender assignment—it is not the case for everyone. Some people assigned male at birth identify as women, some people assigned female identify as men, and some people identify as neither women nor men. This illustrates the difference between, gender assignment, which doctors place on infants (and fetuses) based on the appearance of genitalia, and gender identity, which one discerns about oneself. The existence of transgender people, or individuals who do not identify with the gender they were assigned at birth, challenges the very idea of a single sex/gender identity. For example, trans women, women whose bodies were assigned male and who identify as women, show us that not all women are born with female-assigned bodies. The fact that trans people exist contests the biological determinist argument that biological sex predicts gender identity. Transgender people may or may not have surgeries or hormone therapies to change their physical bodies, but in many cases they experience a change in their social gender identities. Some people who do not identify as men or women may identify as non-binary, gender fluid, or genderqueer, for example. Some may use gender-neutral pronouns, such as ze/hir or they/them, rather than the gendered pronouns she/her or he/his. As pronouns and gender identities are not visible on the body, trans communities have created procedures for communicating gender pronouns, which consists of verbally asking and stating one’s pronouns (Nordmarken, 2013).

The existence of sex variations fundamentally challenges the notion of a binary biological sex. Intersex describes variation in sex characteristics, such as chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals. The bodies of individuals with sex characteristics variations do not fit typical definitions of what is culturally considered “male” or “female.” “Intersex,” like “female” and “male,” is a socially constructed category that humans have created to label bodies that they view as different from those they would classify as distinctly “female” or “male.” The term basically marks existing biological variation among bodies; bodies are not essentially intersex—we just call them intersex. The term is slightly misleading because it may suggest that people have complete sets of what would be called “male” and “female” reproductive systems, but those kinds of human bodies do not actually exist; “intersex” really just refers to biological variation. The term “hermaphrodite” is therefore inappropriate for referring to intersex, and it also is derogatory. There are a number of specific biological sex variations. For example, having one Y and more than one X chromosome is called Kleinfelter Syndrome.

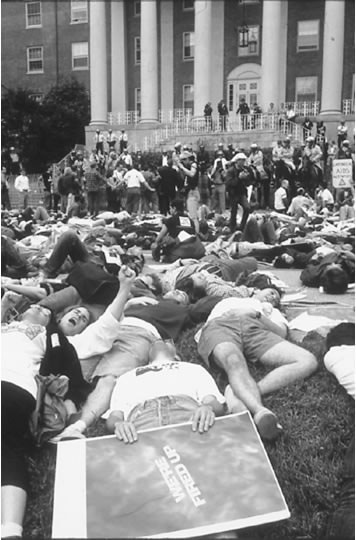

Does the presence of more than one X mean that the XXY person is female? Does the presence of a Y mean that the XXY person is male? These individuals are neither clearly chromosomally male or female; they are chromosomally intersexed. Some people have genitalia that others consider ambiguous. This is not as uncommon as you might think. The Intersex Society of North America estimated that some 1.5% of people have sex variations—that is 2,000 births a year. So, why is this knowledge not commonly known? Many individuals born with genitalia not easily classified as “male” or “female” are subject to genital surgeries during infancy, childhood, and/or adulthood which aim to change this visible ambiguity. Surgeons reduce the size of the genitals of female-assigned infants they want to make look more typically “female” and less “masculine”; in infants with genital appendages smaller than 2.5 centimeters they reduce the size and assign them female (Dreger 1998). In each instance, surgeons literally construct and reconstruct individuals’ bodies to fit into the dominant, binary sex/gender system. While parents and doctors justify this practice as in “the best interest of the child,” many people experience these surgeries and their social treatment as traumatic, as they are typically performed without patients’ knowledge of their sex variation or consent. Individuals often discover their chromosomal makeup, surgical records, and/or intersex status in their medical records as adults, after years of physicians hiding this information from them. The surgeries do not necessarily make bodies appear “natural,” due to scar tissue and at times, disfigurement and/or medical problems and chronic infection. The surgeries can also result in psychological distress. In addition, many of these surgeries involve sterilization, which can be understood as part of eugenics projects, which aim to eliminate intersex people. Therefore, a great deal of shame, secrecy, and betrayal surround the surgeries. Intersex activists began organizing in North America in the 1990s to stop these nonconsensual surgical practices and to fight for patient-centered intersex health care. Broader international efforts emerged next, and Europe has seen more success than the first wave of mobilizations. In 2008, Christiane Völling of Germany was the first person in the world to successfully sue the surgeon who removed her internal reproductive organs without her knowledge or consent (International Commission of Jurists, 2008). In 2015, Malta became the first country to implement a law to make these kinds of surgeries illegal and protect people with sex variations as well as gender variations (Cabral & Eisfeld, 2015). Accord Alliance is the most prominent intersex focused organization in the U.S.; they offer information and recommendations to physicians and families, but they focus primarily on improving standards of care rather than advocating for legal change. Due to the efforts of intersex activists, the practice of performing surgeries on children is becoming less common in favor of waiting and allowing children to make their own decisions about their bodies. However, there is little research on how regularly nonconsensual surgeries are still performed in the U.S., and as Accord Alliance’s standards of care have yet to be fully implemented by a single institution, we can expect that the surgeries are still being performed.

The concepts of “transgender” and “intersex” are easy to confuse, but these terms refer to very different identities. To review, transgender people experience a social process of gender change, while intersex people have biological characteristics that do not fit with the dominant sex/gender system. One term refers to social gender (transgender) and one term refers to biological sex (intersex). While transgender people challenge our binary (man/woman) ideas of gender, intersex people challenge our binary (male/female) ideas of biological sex. Gender theorists, such as Judith Butler and Gayle Rubin, have challenged the very notion that there is an underlying “sex” to a person, arguing that sex, too, is socially constructed. This is revealed in different definitions of “sex” throughout history in law and medicine—is sex composed of genitalia? Is it just genetic make-up? A combination of the two? Various social institutions, such as courts, have not come to a consistent or conclusive way to define sex, and the term “sex” has been differentially defined throughout the history of law in the United States. In this way, we can understand the biological designations of “male” and “female” as social constructions that reinforce the binary construction of men and women.

As discussed in the section on social construction, heterosexuality is no more and no less natural than gay sexuality or bisexuality, for instance. As was shown, people—particularly sexologists and medical doctors—defined heterosexuality and its boundaries. This definition of the parameters of heterosexuality is an expression of power that constructs what types of sexuality are considered “normal” and which types of sexuality are considered “deviant.” Situated, cultural norms define what is considered “natural.” Defining sexual desire and relations between women and men as acceptable and normal means defining all sexual desire and expression outside that parameter as deviant. However, even within sexual relations between men and women, gendered cultural norms associated with heterosexuality dictate what is “normal” or “deviant.” As a quick thought exercise, think of some words for women who have many sexual partners and then, do the same for men who have many sexual partners; the results will be quite different. So, within the field of sexuality we can see power in relations along lines of gender and sexual orientation (and race, class, age, and ability as well).