Cover Image

1

1

Let’s Talk About Suicide: Raising Awareness and Supporting Students by Dawn Schell, Jewell Gillies, Barbara Johnston, and Liz Warwick is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Let’s Talk About Suicide: Raising Awareness and Supporting Students was adapted from Let’s Talk: A Workshop on Suicide Intervention © Dawn Schell. It was shared under a Memorandum of Understanding with BCcampus to be adapted as an open education resource (OER).

The Creative Commons license permits you to retain, reuse, copy, redistribute, and revise this book — in whole or in part — for free providing the author is attributed as follows:

If you redistribute all or part of this book, it is recommended the following statement be added to the copyright page so readers can access the original book at no cost:

Sample APA-style citation:

This resource can be referenced in APA citation style (7th edition), as follows:

Cover image attribution:

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-77420-127-5

Print ISBN: 978-1-77420-128-2

This resource is a result of the BCcampus Mental Health and Wellness Project funded by the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training (AEST).

2

The web version of Let’s Talk About Suicide: Raising Awareness and Supporting Students has been designed with accessibility in mind by incorporating the following features:

In addition to the web version, this book is available in a number of file formats including PDF, EPUB (for e-readers), MOBI (for Kindles), and various editable files. Here is a link to where you can download the guide in another format. Look for the “Download this book” drop-down menu to select the file type you want.

Those using a print copy of this resource can find the URLs for any websites mentioned in this resource in the footnotes.

While we strive to ensure that this resource is as accessible and usable as possible, we might not always get it right. Any issues we identify will be listed below.

There are currently no known issues.

The web version of this resource has been designed to meet Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0, level AA. In addition, it follows all guidelines in Accessibility Toolkit (2nd ed.), Appendix A: Checklist for Accessibility (https://opentextbc.ca/accessibilitytoolkit/back-matter/appendix-checklist-for-accessibility-toolkit/). The development of this toolkit involved working with students with various print disabilities who provided their personal perspectives and helped test the content.

3

Let’s Talk About Suicide: Raising Awareness and Supporting Students was developed under BCcampus’s Mental Health and Wellness Projects with funding from the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training and guidance from an advisory group of students, staff, and faculty from B.C. post-secondary institutions. The purpose of the projects is to provide access to education and training resources for faculty and staff to better enable them to support post-secondary students with their mental health and wellness.

4

We gratefully acknowledge that this facilitator’s guide and the associated presentation have been adapted from University of Victoria’s training Let’s Talk: A Workshop on Suicide Intervention, which was written and developed by Dawn Schell, Manager, Mental Health and Outreach, and Training at the University of Victoria.

A thank you is extended to the B.C. Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training for their support, to BCcampus for their collaborative leadership, to the Mental Health and Wellness Advisory Group, and to the adaptation authors and collaborators whose knowledge and expertise informed this adapted version. See Appendix 3 for the list of authors, contributors, and advisory group members.

The authors and contributors who worked on this resource are dispersed throughout British Columbia and Canada, and they wish to acknowledge the following traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories from where they live and work, including Algonquin Anishinabeg Territory in Ottawa, Ontario; xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) territories in Vancouver, BC; Syilx Okanagan Territory in Kelowna, B.C.; Lək̓ʷəŋən (Lekwungen)/Songhees territories in Victoria, B.C.; and the Kʷikʷəƛ̓əm (Kwikwetlem), xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations in Port Moody, B.C. We honour the knowledge of the peoples of these territories.

5

Let’s Talk About Suicide: Raising Awareness and Supporting Students is an open educational resource and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, unless otherwise indicated. You may retain, reuse, revise, remix, and redistribute this resource without permission. If you revise or remix the resource, it is important to include the copyright holder of the original resource and the authors of this adapted version.

6

This guide is for facilitators to present a two-hour session to post-secondary faculty, staff, or anyone wanting to learn more about suicide and supporting student mental health and wellness. It includes presentation notes, group and reflection activities, and scenarios to give participants a chance to practise. We invite you to augment the training with your own stories and examples.

This session has PowerPoint slides that you can download from the links in the Preparing for the Session section and use while giving the presentation. The slides can be formatted to meet your institution’s guidelines or slide deck templates. You can adjust the slides to fit the needs of your presentation. You may also want to add slides or create handouts with the contact information of counselling services, campus helplines, Indigenous student centres, and other services on your campus that support students.

There are also handouts that facilitators can share with participants. You may want to format these handouts according to your institution’s guidelines (e.g., colours, fonts, logos). You may also adapt the information in them to reflect the needs and concerns of the group you are addressing.

For a detailed breakdown of the workshop, see the Detailed Agenda.

This guide is for facilitators presenting a synchronous session either in person or online, but anyone who wants to learn more about suicide and supporting student mental health can download and use this resource. You do not need to be a facilitator to discover, reflect upon, and use the information and resources provided in this guide. We welcome everyone and hope you find this guide of use in whatever way makes the most sense for you.

Before offering this workshop, facilitators will want to consider their levels of comfort and expertise, as well as their access to support such as a co-facilitator or other resources. Because suicide is a challenging topic, it is helpful if facilitators have experience presenting difficult material in the field of mental health and wellness, an understanding of trauma-informed practice, and the ability to guide and be responsive to adult learners. Facilitators may be a counsellor, an experienced human resources professional, and/or an Elder at your institution. If hiring a third party to deliver the training, consider their credentials and experience in covering complex mental health and wellness.

7

Suicide is very difficult to talk about and a subject many of us would prefer to avoid, but it is also a subject we can’t ignore. Suicide is a prevalent concern around the world, and the second-leading cause of death among 15- to 29-year-olds globally.World Health Organization. (2019). Suicide fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide Post-secondary institutions play a role in raising awareness about suicide and finding ways to best support students. We need to have more conversations about suicide to raise awareness and understanding of how we can support someone who is contemplating suicide.

Let’s Talk About Suicide: Raising Awareness and Supporting Students offers sensitive, respectful, and detailed training on suicide awareness. The training was developed to reduce the stigma around suicide and to help faculty and staff acquire the skills and confidence to ask if a student is considering suicide, listen to that student in a non-judgmental way, and then refer them to appropriate resources. These conversations are not easy and they are never comfortable, but we can all increase our confidence and develop our skills to support students.

I

1

A set of presentation slides is available to accompany both in-person and online workshops. These slides can be adjusted to meet the needs of your participants and formatted to meet your institution’s guidelines or slide deck templates. You can download the slides here: BCcampus Let’s Talk About Suicide [PPTX].

There are also handouts available for download:

This training opens up the conversation about suicide to reduce negative stigma surrounding suicide and decrease anxiety about talking to others about suicide. Key learning points of the seminar include:

To prepare to facilitate this workshop, consider the following:

You will need the following:

If your video-conferencing software allows you to create breakout rooms, you can have people work together in smaller groups. Take some time before the session to get comfortable with the breakout room set-up process. It can be helpful to have someone assist you with setting up the breakout rooms, so you can facilitate the session while they handle the technical issues.

Breakout rooms will work well for discussing the scenarios, but you will want to do some advance preparation. It may be easiest to put the scenarios in the chat, so have the scenarios ready to add to the chat prior to the session. During the session, you can then assign each group to a specific breakout room to discuss the different scenarios. Alternatively, you could move people into breakout rooms and then visit each room to verbally provide a scenario to each group.

2

Acknowledging the traditional lands of the Indigenous people on which you live, work, and study is an important way to begin an event or meeting and can be included as part of classroom activities and taught to students. Meaningful territory acknowledgements allow you to develop a closer and deeper relationship with not only the land but the traditional stewards and peoples whose territory you reside, work, live, and prosper in. For more information on giving a territory acknowledgement, see Opening the Session.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action explicitly state that each of us as members of Canadian society have a direct responsibility to contribute to reconciliation; how we discuss colonization in relation to mental health and suicide is a direct response to that responsibility.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is an international instrument adopted by the United Nations on September 13, 2007, to enshrine (according to Article 43) the rights that “constitute the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.” UNDRIP was adopted into the B.C. provincial legislature on November 26, 2019. Centring the history of colonization as a background and framework to mental health from a historical and current ongoing struggle is in direct response to our legal and moral obligation as members of Canadian society.

Indigenization is a process of naturalizing and valuing Indigenous knowledge systems.Antoine, A., Mason, R., Mason, R., Palahicky, S., & Rodriguez, C. (2018). Pulling together: A guide for Indigenization of post-secondary institutions. A professional learning series. Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationcurriculumdevelopers/; Little Bear, L. (2009). Naturalizing Indigenous knowledge, Synthesis paper. Canadian Council on Learning. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education/21._2009_july_ccl-alkc_leroy_littlebear_naturalizing_indigenous_knowledge-report.pdf In the context of post-secondary institutions, this involves bringing Indigenous knowledge and approaches together with Western knowledge systems. This benefits not only Indigenous learners but all students, staff, faculty, and campus community members involved or impacted by Indigenization.

As you adapt this training for your particular context, consider how and in what ways you might interweave Indigenous content and approaches. Here are some examples of how you might include an understanding of Indigenous ways of knowing and being:

As you do this work, as an Indigenous or non-Indigenous person, you will want to continue to draw upon and build on existing relationships with Indigenous people, both within and outside of your institution. As a way of continuing to work in intentional and respectful ways, you may want to reflect on questions such as:

Elders have always been the foundation for emotional, social, intellectual, physical, and spiritual guidance for Indigenous communities. As you find ways to naturalize Indigenous context, perspectives, and traditional ways of being into your training, we recommend you consider inviting an Elder or Knowledge Keeper from your local community to support your sessions. One way of doing this is to speak with your Indigenous Student Services Department at your institution and share with them some of the recommendations in this guide and see how they might wish to support this work.

Not all institutions will have an Elder-in-Residence but each should have ways for you to contract an Elder or Knowledge Keeper to come in and support your work. Elders and Knowledge Keepers often support the whole post-secondary institution community, not just the Indigenous students. Involving Elders and Knowledge Keepers can help support reconciliation by helping to build respectful, reciprocal relationships that are deep and meaningful.

Whenever you plan to bring in a community member, Elder, or Knowledge Keeper, it is important to plan for the honorarium required to remunerate them for their time and sharing their lifetime of wisdom and traditional teachings. In many communities, it is seen as most respectful to offer payment on par with what you would pay a Ph.D. holder to do a keynote presentation. However, consulting with the Indigenous services staff at your institution on what is a typical amount for this type of event is also a good practice.

3

Participants need to feel comfortable, safe, and respected during the seminar. As you prepare to facilitate, you will want to consider factors such as when and where to hold the training, key messages on promotional materials, whether to use group guidelines, how to ensure diverse representation, and ways of working with co-facilitators or guests. In this section, we discuss several strategies for helping to create a positive learning space.

Facilitators have an enormous role to play in setting the tone for a session. As people enter the space (online or in person), you can welcome them and help them get oriented. You can let them know if you’ve started or whether you’re waiting for a few more people and share housekeeping information such as where the bathrooms are, where they can put their things, or how to use online interactive features. You may want to consider using a breathing exercise together or an icebreaker activity to help put people at ease. As you begin your session, you can use opening questions that help create inclusivity such as correct pronouns, check-in questions, or information about accessibility needs and requests.

It is important to hold space in a presentation for people’s feelings and experiences – shared or not. However, there also need to be boundaries that will enable the training to move forward and be completed within the stated time frame.

You will want to establish at the beginning that the training is a learning space and not a counselling session. (You may also want to send an email to all participants with this message prior to the session.) If a participant is starting to take over the discussion with their personal experiences, you will want to gently redirect the conversation back to the material that you need to cover. It is a good idea to stay after the session is over to talk to any participants one-on-one.

It’s also important to provide a clear scope at the beginning to reassure participants who worry that they must “save” a student who expresses suicidal thoughts.

It can be helpful to ask participants to agree to a list of guidelines or a code of conduct when they register or sign up for the training. You can either send the group guidelines to participants before the session or you can take some time at the beginning of the session to establish the guidelines together.

Or, you might share a list of guidelines at the beginning of the training and ask learners if they feel comfortable with them or if they have something they would like to add or change.

Group guidelines can be an important tool for supporting safer discussion about difficult topics. You can remind participants of the guidelines if the discussion is getting difficult. Important group agreements relate to listening to and showing respect for others (e.g., not talking when others are speaking, not making rude comments, not talking on the phone), confidentiality, and participation.

It’s also important to establish guidelines about how much people will share. Suicide is a topic that could trigger some people and remind them of past experiences.

Group guidelines come in all shapes and sizes. Some groups have a few guidelines while others have many. Here are suggestions of possible guidelines:

Content warnings (also called trigger warnings) are a statements made prior to sharing potentially difficult or challenging material. The intent of content warnings is to provide learners with the opportunity to prepare themselves emotionally for engaging with the topic or to make a choice to not participate.

Different departments and institutions will have different approaches to content warnings and this may guide your decision about including content warnings on registration or sign-up forms, in learning materials, and in the learning environment. Below is an example of a content warning:

“We will be discussing topics related to suicide in this training. During the training, you can choose not to participate in certain activities or discussion and can leave the room at any time. If you feel upset or overwhelmed, please know that there are resources to support you.”

There are a number of other facilitation strategies you may want to consider in addition to or instead of a content warning:

Some people participating in the session may have direct experience with someone close to them taking their own lives. There are a number of strategies you can use to help create a trauma-aware learning space.

Sometimes, during training on suicide awareness, a participant may be reminded of someone they have lost from suicide. Before you start facilitating in this area, you will want to ensure that you are knowledgeable about receiving disclosures and available supports and resources on campus and in the community. Some institutions have developed practices such as expedited counselling for participants who might need support after a training session or making intensive crisis supports available for a short time after a training or particular initiative.

At the beginning of the training, acknowledge that the topic of suicide is difficult and let participants know that they have the right and freedom to take care of themselves in a way that works for them. In particular, let participants know that they can leave the room or choose not to participate in an activity. You could say something like “If at any time you feel you need to leave, that’s fine with me. You are empowered to take care of yourself.” You can also let learners know that reactions to difficult material can sometimes be delayed and that they may wish to connect with you a few days after the training or to access support from family, friends, or other people in their lives.

If you feel comfortable, you can share information about grounding activities that may be helpful to participants during the session. Grounding activities, such as breathing exercises, are simple activities that can help people to relax, stay present, and reconnect to the “here and now” following a trauma response. Examples include pressing or “rooting” your feet into the ground, breathing slowly in and out for a count of two, repeating a statement such as “I am safe now. I can relax,” or using your five senses to describe the environment in detail.

If you do notice that someone has left the group and you suspect that they were reminded of previous trauma by the session, follow up with them one-on-one after the session to check in and offer them any resources that you think might be helpful to them.

During the training, if the conversation becomes intense or you believe that a number of participants have become overwhelmed or affected by the discussion, it can be helpful to take a break or use an activity that involves the body or movement to help people reconnect to the present moment.

Let learners know that you will be available after the training if they would like to debrief or share their responses to the session or how they are feeling. If possible, schedule at least 30 minutes after a session so that you can be available to your learners. If you are delivering training in an online context, you can let learners know that they can private message/email you.

Participants may need some time near the end of the session to ask questions, share a reflection, or simply sit with what they heard and discussed. If possible, try to ensure you have this time built in at the end so no one feels rushed when concluding the session.

Plan to stay after the session to talk to any participants who have questions or concerns they want to discuss. If you are concerned about a participant, ask them if they would find it helpful for you to check in with them later in the day or the following day. You could also ask them if they have a friend or family member that they might find it helpful for them to speak with following the training. If so, help them make a plan to connect with them, e.g., via phone or text or in person or at a certain time.

Facilitating conversations about suicide can be challenging. Participants likely bring many different experiences, assumptions, ideas, and worries about how best to support students who are struggling with these issues.

It’s important to create a space where people feel safe and supported so they share and listen to others with respect and empathy. This section offers ideas and tips for creating such an environment, but facilitators also have a time limit in which to present material. It’s important to keep an eye on the clock and know how, and when, to direct people’s attention to the next topic.

As mental health and wellness affects all parts of our lives, participants may bring up related issues or concerns or they may disclose that someone they know has taken their own life or attempted suicide. Below are some questions that might come up during the presentation, with suggestions for responses. The goal is to acknowledge people’s comments, thank them for their contribution, and point them to resources they may find helpful. Then the discussion can move back to the specific topic at hand.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/suicideawareness/?p=58

I’ve read that the suicide rate for young people is very high. Why isn’t this institution doing more to support students struggling with mental health?

I’ve had students mention they are considering suicide and it made me feel helpless and worried. Will this training actually help me?

I don’t feel like I can deal with a student who is so distressed they are considering suicide. What should I do?

Why are you adding to my workload?

I tried to help a student and it went badly.

What teaching practices can I use in my classroom to support student mental health and well-being?

What about the support for the mental health and well-being of faculty and staff?

While facilitating, you are likely to encounter challenging moments when you may not be sure how to respond. Someone may start to dominate the discussion with their own story of suicide, a participant may make a negative remark about suicide, or the conversation may shift in a direction that makes you concerned for the comfort of other participants.

Below are some potential responses for bringing participants back to the topic or handling challenging moments:

We should avoid language that sensationalizes or normalizes suicide or presents it as a solution to problems. For example the terms “failed attempt” or “successful” or “completed attempt” are best avoided as they depict suicide as a goal, project, or solution. Below are some guidelines for language when talking about suicide.

| Avoid Using | Use Instead | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Committed suicide |

Note: If you are unsure of a student’s level of proficiency in English, you may want to use the direct terms “killed themselves” or “ended their life” instead of “suicide.” |

Using the word “commit” implies that suicide is a crime (we commit crimes). This perpetuates stigma, and stigma stops people from talking. People will be less likely to talk about their suicidal feelings if they feel judged. |

| Unsuccessful or failed suicide |

|

People who have attempted suicide often say, “I couldn’t even do that right… I was unsuccessful, I failed.” In part this comes from unhelpful language around their suicide behaviour. Any attempt at suicide is serious. People should not be further burdened by whether their attempt was a failure, which in turn suggests they are a failure. |

| Successful or completed suicide |

|

Talking about suicide in terms of success is not helpful. If a person dies by suicide, it cannot ever be a success. We don’t talk about any other death in terms of success: we would never talk about a successful heart attack or stroke. |

Self-care and community care are about looking after yourself and those around you. Facilitating a session about suicide can range from satisfying and rewarding to challenging and overwhelming. It is important to make sure that you are able to take the time to take care of yourself and that you are willing to reach out to co-workers, friends and family, or professional support if needed.

Ideally, you will be in a situation where you are able to deliver the training with a co-facilitator. Not only is this helpful if a learner needs support during a session, it also helps to have someone with whom to share the joys and challenges of facilitation. After a session, plan for time afterwards to check in with each other about your experiences and any successes or challenges in facilitating. This allows for time to reflect on issues related to your own mental health, to consider any feedback that you received from participants, and to discuss any facilitation successes and challenges. If you are facilitating alone, you might use the time after a session to reflect or use a journal to make notes as a way of processing the experience, or you may want to debrief with a colleague or counsellor.

Taking time after a session to debrief can be a helpful way to care for yourself. Here are some sample debriefing questions.

4

This agenda offers some suggested times for the different sections of the workshop. You may need to adjust these depending on the needs of the group, your facilitation experience, and any time constraints you face.

| Activity | Time |

|---|---|

Welcome

|

5 min |

Session Overview and Guidelines for Participants

|

10 min |

Why We Need to Talk About Suicide

|

15 min |

Exploring Our Own Feelings About Suicide

|

15 min |

Observing and Recognizing the Signs

|

15 min |

Responding

|

15 min |

Referring

|

5 min |

Scenarios – Practising What To Say

|

20 min |

Maintaining Boundaries

|

10 min |

Summary and Closing

|

10 min |

II

5

This section describes how to open the session and prepare participants to engage with the material. This includes:

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/suicideawareness/?p=68

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

Welcome participants and open with a territory acknowledgement. If you’re unsure of your territory, the website Native-Land.ca is a helpful resource.

Territory Acknowledgement and Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Being

A meaningful territory acknowledgement allows us to develop a closer and deeper relationship with not only the land but also the traditional stewards and peoples whose territories we reside, work, live, and prosper in.

Acknowledging the territory within the context of mental health and well-being can open a person’s perspective on traditional ways of knowing and being, stepping out of an organizational structure, and allowing participants to delve into their own perceptions, needs, and abilities.

Territory acknowledgements are designed as the very first step to reconciliation. What we do with the knowledge of whose traditional lands we are on is the next important step.

Some questions to consider as you acknowledge your territory:

Should your institution have an approved territory acknowledgement please use that to open the session; however, we invite you to consider how to make that institutional statement more personal and specific to you, in that moment and in the work you are about to delve into with your participants.

After the welcome, introduce yourself. You could ask participants to very briefly introduce themselves, or you may want to start the session with a short participant check-in as a way to invite people into a learning space. You could ask participants to share their name, where they work, and what they are hoping to get out of the session. If you’re offering the session online, you could do an online poll that asks people to choose the type of weather that matches how they are feeling. There are many different ways to have participants check in with themselves and the group, and we invite you to use questions and reflections that are meaningful to you and the group.

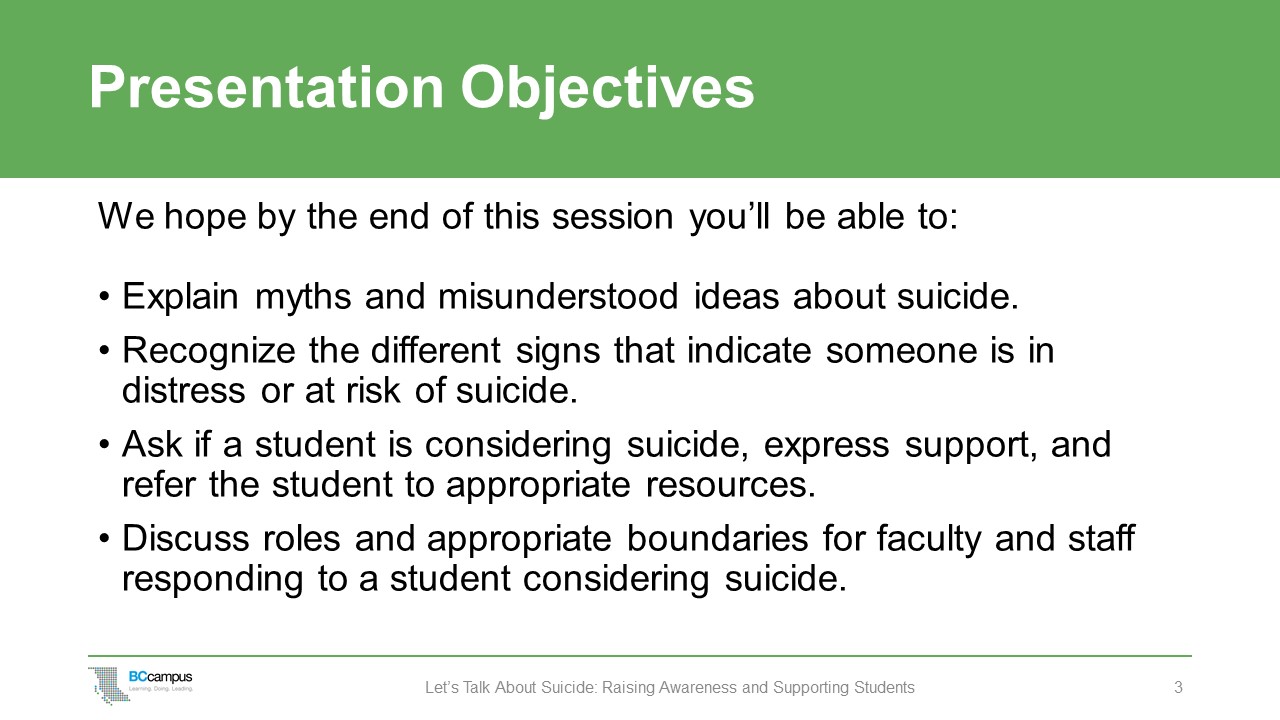

Review the overall goal of this presentation: to help faculty and staff develop the knowledge, skills, and confidence to support students who are in distress and possibly thinking of suicide.

After participating in the presentation, participants will be able to:

Participants will leave this session with a clear understanding of their role in responding to students in distress and have basic tools for approaching and referring students to campus resources and crisis lines.

Suggest that as people engage with the presentation, they reflect and think about how the information might apply to situations they have already had with students, or situations that they can imagine coming up in their role as faculty or staff.

Encourage participants to provide feedback and share their input during the discussions as this helps improve the learning opportunities. Also encourage people to jot down notes during reflection activities. Encourage them to ask questions if they have any questions during the session.

Let everyone know that after the presentation, they will have access to printable (PDF) handouts. If possible, have a handout with contact information of your institution’s support services for students.

If you are giving this session online, remind online participants that they can turn off their cameras and move around the room during the session. Ask them to be mindful of using the mute button to reduce noise in the online space. You may also want to encourage participants to use the chat feature to ask questions and make comments.

To create a safe space, spend some time talking about how the topic of suicide can be sensitive for all of us and can bring up memories of people we know, love, and have lost. Many of us have been affected by suicide in some way.

Tell participants that self-care is not an afterthought, and they should keep the concept of self-care in mind while going through this session. Remind them that they are not alone, they are all colleagues, and they are here to support each other and share resources. This is meant to be a supportive community.

Remind people to take care of themselves in whatever way makes sense, including permission to “pass” or to not share, permission to take time or to leave the room. People should feel free at any time to pause, take a break, stretch, and ground themselves. To feel emotionally touched is expected but can be surprising and unsettling.

For in-person sessions, you could suggest that if a participant does need to leave a session that they give a thumbs-up as they go to let you know they’re okay. Tell everyone that if you don’t see a thumbs-up, you’ll ask a colleague to look for the participant outside the session to make sure they are all right.

Also, remind participants that they can share at the level that they feel comfortable with. Suggest that if anything comes up in the session that feels too important or difficult to handle on their own, people shouldn’t hesitate to reach out to the appropriate services – a counselling office or an employee assistance program – to debrief or discuss it further.

ACTIVITY: Breathing Exercise to Ground Yourself

To begin, you could have the group engage in some breathing exercises to set the tone of the session, to give participants a few moments to become aware of their own emotional well-being, and to practise a stress management technique.

If participants start to feel overwhelmed at any point, suggest they try box breathing. Box breathing is a very simple stress management exercise that can be practised anywhere. You can practise box breathing for only a minute or two and experience the immediate benefits of a calm body and a more relaxed mind.

Simply relax your body and do the following:

It is helpful to set some expectations and boundaries for the discussion. Remind participants that this is a learning environment, and not a therapy group. Sometimes a topic like suicide brings things up for people, but what comes up in this room – whether in person or online – stays in the room. It is also expected that participants will be non-judgmental of each other and show extra sensitivity when engaging in discussion during the seminar. This is about gaining a little more comfort and confidence in dealing with this topic.

You could ask participants to share ideas for group guidelines at the beginning of the session, or you could share a list of guidelines before the session begins to save time during the session. Some examples of group guidelines:

REFLECTION: How Confident Do You Feel?

Ask the participants to take a moment to reflect on how confident they feel about talking to someone who says they are suicidal. Ask them to rate themselves on a scale from 1 to 10 (1 being very little confidence and 10 being very confident). Tell them that this is information that is meant only for them and they will not be asked to share it. Let them know you will take a moment at the end of the session to re-assess their confidence level.

Take this opportunity to talk about the difference between confidence and comfort levels. The aim of the session is not to make them comfortable as a conversation about suicide is never a comfortable conversation. The aim of the session is for participants to feel more confident about going into these conversations.

6

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/suicideawareness/?p=81

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

The Tree of Life

For the cover of this guide and for many of the slides, this guide uses images of trees and forests. Trees sustain life on earth and are a powerful symbol of growth, interconnection, resilience, and strength. The red cedar is a particularly important tree to many Indigenous Peoples on the west coast of British Columbia. Below is one perspective on the importance of the red cedar tree to Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw people.

In the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw Nation, the red cedar is known as our tree of life. This tree expresses our responsibility as stewards of the land. The roots of a red cedar tree go deep, and when they are connected to other trees, they can share natural resources to support the health of the forest communally. Ever since the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw people came into existence thousands of years ago, from our birth to the ceremony mourning our passing as individuals, the tree of life has played – and continues to play – a crucial role in every aspect of our lives.

Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw people have sacred teachings on sustainably harvesting the bark of red cedars for our regalia, our woven cedar hats, or our headbands; this regalia plays a vital role in our Potlatch ceremonies. The tree of life is often in our artwork, our regalia; it represents the spirit of hope our communities have for our families, our communities, and the other nations interconnected with ours.

The connection between our traditional teachings and protocols around red cedars is very similar to how we support people in mental health distress. A sense of connection, community, dignity, and respect are essential.

So much of a tree’s determinants of health lie within the soil, a place we cannot see. When supporting a student who is very distressed and possibly considering suicide, it is important to remember all of the protective factors they may have below the surface:

Our role in supporting students with suicidal ideation is to determine the most appropriate resources to help the student, the same way the roots of the tree of life share their resources to the forest around them.

—Jewell Gillies, Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw Nation (Ukwana’lis, Kingcome Inlet, B.C.)

Video: Live Through This

Live Through This is a series of portraits and true stories of suicide attempt survivors. Its mission is to change public attitudes about suicide. To start this section, you may want to show a short four-minute video of suicide survivors from the Live Through This website. Alternatively, you could share the link with participants prior to the session to help them prepare.

Because we don’t talk about suicide a lot, people often have a lot of questions and there are a lot of misunderstood ideas and myths about suicide. Let’s take some time to talk about some of these myths.

ACTIVITY: Talking About Myths and Misunderstood Ideas

In small groups, have participants discuss one of the myths below. You could have each group discuss a different myth and then bring their thoughts back to the larger group for a larger group discussion. Also ask them to consider the following two questions:

![]() Adaptations

Adaptations

As a large group, ask people to share their thoughts about the myths and give everyone an opportunity to ask questions. If online, you could have people share thoughts and ideas in chat.

Debrief with the group. Below are some talking points about the myths.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/suicideawareness/?p=81

Myth: People who talk about suicide are only trying to get attention. They won’t really do it.

Few people die by suicide without first letting someone else know how they feel. Those who are considering suicide give clues and warnings as a cry for help. In fact, most seek out someone to rescue them. Over 70% who do threaten to carry out a suicide either make an attempt or die by suicide.

It is best to treat talk and threats about suicide seriously. Research indicates that up to 80% of suicidal people signal their intentions to others, in the hope that the signal will be recognized as a cry for help. These signals often include making a joke or threat about suicide, or making a reference to being dead. If we do take someone seriously and ask them if they mean what they are saying, the worst that can happen is we will learn that they really were not serious. Not asking about suicide could result in a far worse outcome.

Myth: If someone is seriously contemplating suicide, they don’t want to make a decision to live.

We know that those at risk for suicide do not necessarily want to die, but do want help in reducing the pain they are experiencing so that they can go on to lead productive, fulfilling lives. There is a lot of ambivalence surrounding the decision to take one’s own life, and by recognizing this, and discussing it, we can help the suicidal person start to recognize alternative options for managing their suffering. Often people who are suicidal are experiencing intolerable emotional pain, which they believe to be unrelenting. They often feel hopeless and trapped. By helping them to recognize and explore alternatives to dying, you are planting the seeds of hope that things can improve.

Myth: Talking about suicide to a person will make them suicidal.

There is no research evidence that indicates talking to people about suicide, in the context of care, respect, and prevention, increases their risk of suicidal ideation or suicidal behaviours. Research does indicate that talking openly and responsibly about suicide lets a person who is potentially suicidal know they do not have to be alone, that there are people who want to listen and who want to help. Most people are relieved to finally be able to talk honestly about their feelings, and this alone can reduce the risk of an attempt.

Myth: If someone makes a suicide attempt, but does not die, they are just looking for attention.

At some level, all suicide attempts are usually because an individual is experiencing high levels of emotional pain and desperation. It is important to treat all attempts as serious. Once an attempt is made at any level of lethality, the risk for suicide or more serious suicide attempts increases significantly.

Myth: Self-harm is always a sign that someone is contemplating suicide.

Self-harm is the intentional and deliberate hurting of oneself. It is very upsetting to notice that someone is self-harming, but self-harm does not necessarily mean a person is thinking about suicide. Self-harm is often a coping method, a way to deal with feelings such as anxiety, anger, or pain. It can also be a way that people communicate their emotional pain and a way to reach out for help. Although self-harm is not the same as suicide, self-harm can become suicide, and it is important that this person get help.

Note: If participants have questions specifically about self-harm, suggest that they talk to you after the session for resources to understand more about it. A very good resource on self-harm is Self-Injury Outreach and Support.

Every expression of suicide needs to be taken seriously because no one can predict who will die by suicide even though many people have had thoughts of suicide at some point in their lives. Anyone can be at risk for suicide. Let’s have a look at some statistics for more insight.

An average of 10 people die by suicide each day in Canada.

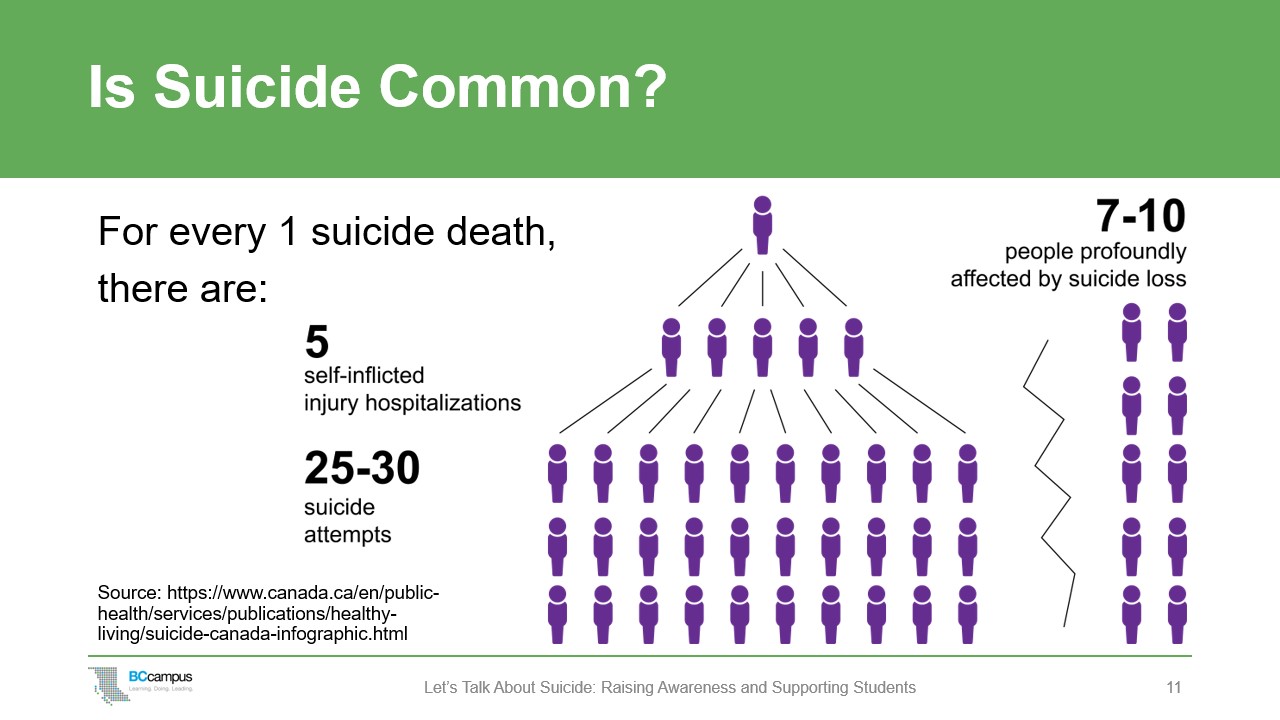

For every 1 suicide death there are:

In the post-secondary context, Canadian data from the 2019 National College Health AssessmentAmerican College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Canadian Reference Group Data Report Spring 2019. Silver Spring, MD: American College Health Association; 2019. https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_SPRING_2019_CANADIAN_REFERENCE_GROUP_DATA_REPORT.pdf tells us that:

(For this survey, 58 Canadian post-secondary institutions self-selected to participate and over 55,000 surveys were completed.)

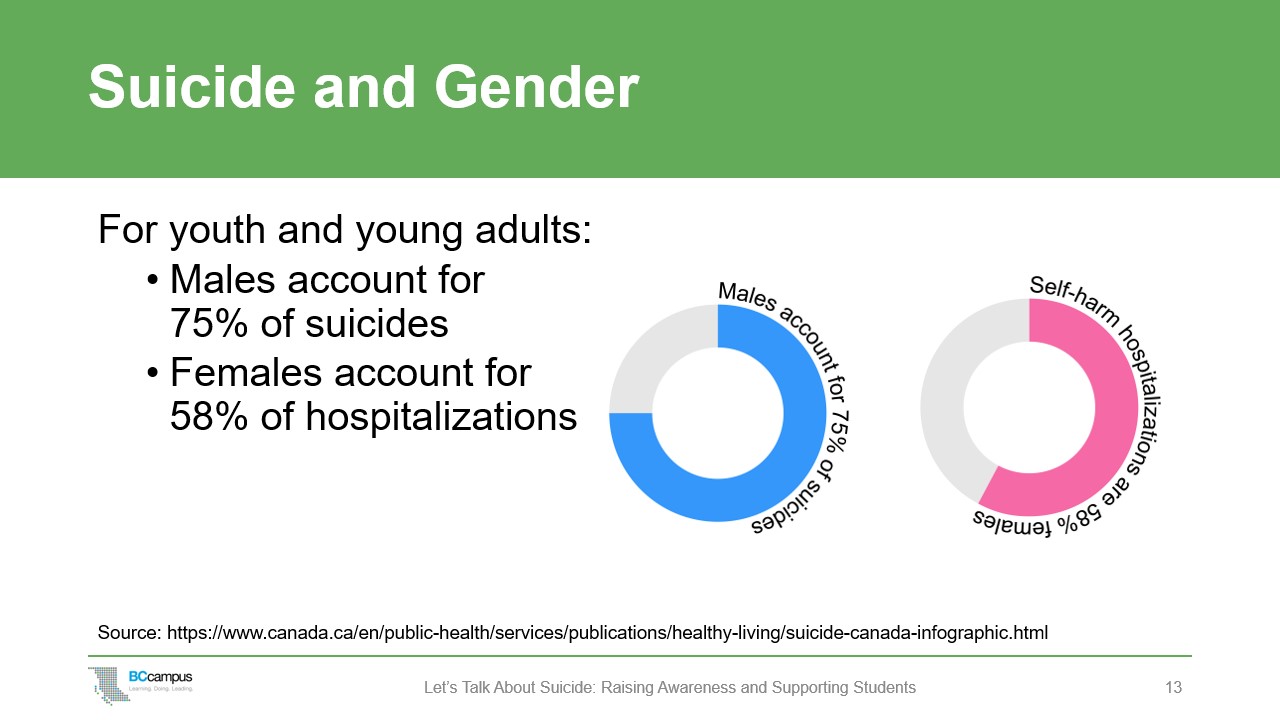

When we consider gender, Statistics Canada tells us that males account for 75% of suicide, but females account for 58% of hospitalizations for attempted suicide.

Women are three to four times more likely to attempt suicide than men, but men are three times more likely to die by suicide than women.Canadian Mental Health Association. (2016). Preventing suicide. (2019, July 22). https://cmha.ca/documents/preventing-suicide There are several reasons for this:

Among non-binary students, the suicide rate is very high: 44% of non-binary students had seriously considered suicide, and 17% had attempted suicide in the past year.McCreary Centre Society. (2018). B.C. adolescent health survey. https://www.mcs.bc.ca/about_bcahs

Stats don’t take into account the impact that suicide has on others. For each death by suicide it has been estimated that the lives of 7 to 10 people will be affected.

The more we have these types of conversations, the more of the iceberg is brought to the surface.

Statistics can quickly show how prevalent suicide or thoughts of suicide are among post-secondary students. The slides include information about suicide in Canada. However, there may be statistics on student mental health and suicide at your institution or in your community that you can use. Or you may want to share information and statistics about groups at higher risk of suicide. Some examples to consider:

Or you may want to use both quantitative data and qualitative data (for example, brief statements from students).

Suicide is a complex topic and there is no single cause that makes an individual suicidal. When a person feels helpless or alone, overwhelmed by pain, fear, and suffering, their hope wanes and they may consider ending their life.

Many people experience passing thoughts of ending their lives without ever having any intention to act on those thoughts. Suicidal thinking becomes more concerning when it is persistent and driven by increased emotional distress. When a person’s thoughts become directed toward how and when they might kill themselves and actual gestures or attempts elevate the overall level of risk.

Factors that may increase risk of suicide:

Protective factors include:

When we talk about mental health and suicide risks, we also need to be aware of factors like race, sexual orientation, social class, age, disability, and gender and the unique life experiences and stressors that accompany them. Some students face inequality, discrimination, and violence because of their race or gender orientation. These unique and specific stressors impact mental and physical health, and these students often experience greater mental health burdens while at the same time facing more barriers to accessing care. Research and statistics tell us that suicide risk is higher for Indigenous and LGBTQ2S+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirit) than it is for the general population.

Suicide among Indigenous people is significantly higher than the general population. Estimates suggest that, in some years, the suicide rate for Indigenous people in specific communities is as much as 30% higher than that for non-Indigenous people.Statistics Canada. (2019). Suicide among First Nations People, Métis and Inuit (2011–2016): Findings from the 2011 Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohort (CanCHEC). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/ n1/daily-quotidien/190628/dq190628c-eng.htm

Suicide rates are highest for youth and young adults (15 to 24 years) among First Nations men and Inuit men and women. However, there is great variability in suicide rates at the community level; some Indigenous communities may have a very high suicide rate; other communities may have a very low rate.

For Indigenous communities, high rates of suicide are connected to a variety of factors including the historical and ongoing trauma from colonialism, systemic racism, discrimination, and the loss of culture and language. The impact of residential schools and other colonial policies have created ongoing adversity for Indigenous people, and these effects have been passed on from one generation to the next, causing intergenerational trauma.

Many Indigenous people lack trust in educational and health care institutions because of the negative or traumatic experiences they or family and friends have experienced in the past. The 2020 report In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care reported on the widespread systemic racism against Indigenous peoples in the B.C. health care system. The study reported that 84% of Indigenous people described personal experiences of racism and discrimination that discouraged them from seeking necessary care.Turpel-Lafond, M. E. (2020). In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care. https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2021/02/In-Plain-Sight-Data-Report_Dec2020.pdf1_.pdf

It is important to note, however, that while the suicide rate is higher for Indigenous people compared with non-Indigenous people, not all Indigenous communities have regular incidents of suicide. In communities where there is a strong sense of culture, community ownership, and other protective factors, it is believed that there are much lower rates of suicide and sometimes none at all.Kirmayer, L., et al. (2007). Suicide among Aboriginal people in Canada. Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

People who are LGBTQ2S+ are at a much higher risk than the general population for mental health disorders, substance abuse, and suicide. Homophobia and negative stereotypes about being LGBTQ2S+ can make it challenging for a student to let people know this important part of their identity. When people do openly express this part of themselves, they worry about the potential of rejection from peers, colleagues, and friends, and this can exacerbate feelings of loneliness. Health needs may be unique and complex for some LGBTQ2S+ people, and health care settings can feel unsafe or uncomfortable for many.

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth are more at risk for suicide than their straight peers. They are five times more likely to consider suicide and seven times more likely to attempt suicide.Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2008). Suicide risk and prevention in gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender youth. Education Development Center, Inc. http://www.sprc.org/sites/default/files/migrate/library/SPRC_LGBT_Youth.pdf

Transgender people are at an even greater risk for suicide as they are twice as likely to think about and attempt suicide than LGB people.Haas, A., et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(1),10-51. DOI: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038; McNeill, J. et al. (2017). Suicide in trans populations: A systematic review of prevalence and correlates. Psychology of Sexual Orientation. DOI:10.1037/sgd0000235.; Irwin, J. et al. (2014). Correlates of suicide ideation among LGBT Nebraskans. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(8), 1172–1191. Studies have shown that 22% to 43% of transgender people have attempted suicide.Bauer, G., et al. (2015). Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: A respondent driven suicide risk sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-015-1867-2. Transgender people face unique stressors, including stress from being part of a minority group, as well as stress related to not identifying with one’s biological sex. Transgender people also experience higher rates of discrimination and harassment than their cisgender counterparts and, as a result, experience poorer mental health outcomes.

While there is a growing awareness of the needs and challenges faced by LGBTQ2S+ community members, much still needs to be done to create truly inclusive and safe spaces within health and educational environments.

We need to take care to understand and acknowledge oppressions faced by Indigenous people, LGBTQ2S+, people with disabilities, and people from racialized and other marginalized groups. By providing a culturally safe environment, we can all play a role in ensuring that each student feels their personal, social, and cultural identity is respected and valued.

It is helpful to know the campus and community resources for students from marginalized groups. Connecting an Indigenous student to an Elder or to someone from Indigenous services or introducing an LGBTQ2S+ student to a pride centre on campus can help to reduce feelings of isolation and help students feel heard and supported. We’ll talk more about supports and referrals a bit later in the session.

ACTIVITY: Discussion

Either in small groups or as a large group, ask participants to discuss the following:

7

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/suicideawareness/?p=86

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

Before we start to talk about how we can provide a support role for others, let’s take a moment to explore our own feelings and attitudes around suicide. It’s helpful to think about this ahead of time so that you don’t bump into surprising feelings or attitudes while trying to support someone; this way you can make sure the experience is more about them. You don’t have to do a complete assessment of yourself at this point, but this is an invitation to consider your own feelings and attitudes because you likely do have some beliefs and thoughts about this topic.

It’s okay to have different feelings and attitudes about suicide. Some of these beliefs will be more helpful than others. The goal is to forget about some of the less helpful ones to make sure that the interaction is about supporting someone else.

There are people who believe that suicide is wrong. We’re not here today to argue about the ethics or morality of it. We’re going to focus on questions, feelings, worries, and thoughts. Please be honest but also remember that there may be people here who have experience with loved ones dying by suicide. Let’s make sure we treat each other with compassion and respect.

ACTIVITY: What Questions and Worries Do You Have?

Ask participants to divide up into pairs to discuss this question:

Imagine that you are able to ask someone if they are thinking about suicide. What questions, thoughts, beliefs, worries, feelings come up for you? What are your worst fears?

As a large group, ask people to share their responses. (If online, people could share their responses in the chat.) Responses may include:

![]() Adaptations

Adaptations

You could also ask participants to think about their own beliefs and ideas about who does or does not end their own life. For example, a person may assume that seemingly in-control people are not at risk of suicide. Or perhaps they hold stereotypes or ideas about specific groups of people and suicide. This is a good opportunity to explore any biases.

The thought of asking someone about suicide can be overwhelming. One concern that people often have is that if they bring up suicide and a person isn’t considering it, this person may start thinking about it as an option. That is untrue. Asking about suicide will not put the thought into someone’s mind. It can give the person a sense of relief, (for example, “Finally, someone has seen my pain,”) or give them permission to open up further about something they have been hiding.

Before having a difficult conversation, there are a few things to first ask yourself. If there is a student you think may be at risk of suicide, first think about your own emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and values. Ask yourself how you feel about starting this conversation with a student. You may realize you are not emotionally ready to talk to the student, and this is okay. You can reach out to other people on campus, such as a counsellor, to get their advice and support.

If you feel ready to have this sensitive conversation, you will want to think about how and where the conversation will happen. You will want to:

III

8

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/suicideawareness/?p=106

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

There are thoughts, feelings, physical effects, actions, and events that are common to a person’s experience and may give us clues to the possibility of suicide.

We need to be observant and notice these things, which by themselves may not be definitive indicators but will give us valuable clues to probe further. Remember:

What are possible thoughts that people who are contemplating suicide might be having?

They may be thinking:

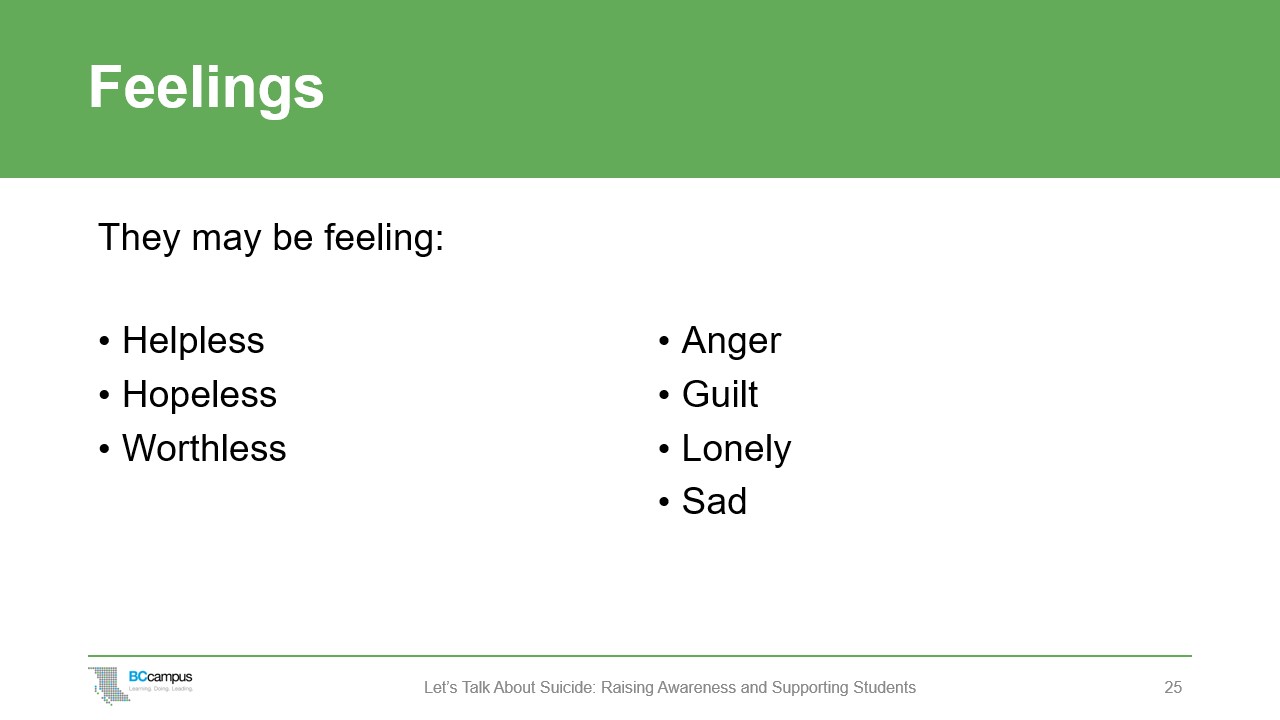

If you hear a student say they feel helpless, hopeless, or worthless, these are red flags that they may be thinking about suicide. They may also be feeling angry, guilty, lonely, or sad.

People may feel ambivalent about dying. There is a huge difference between wanting to die and not wanting to live. Suicidal thoughts often come when pain exceeds a person’s resources.

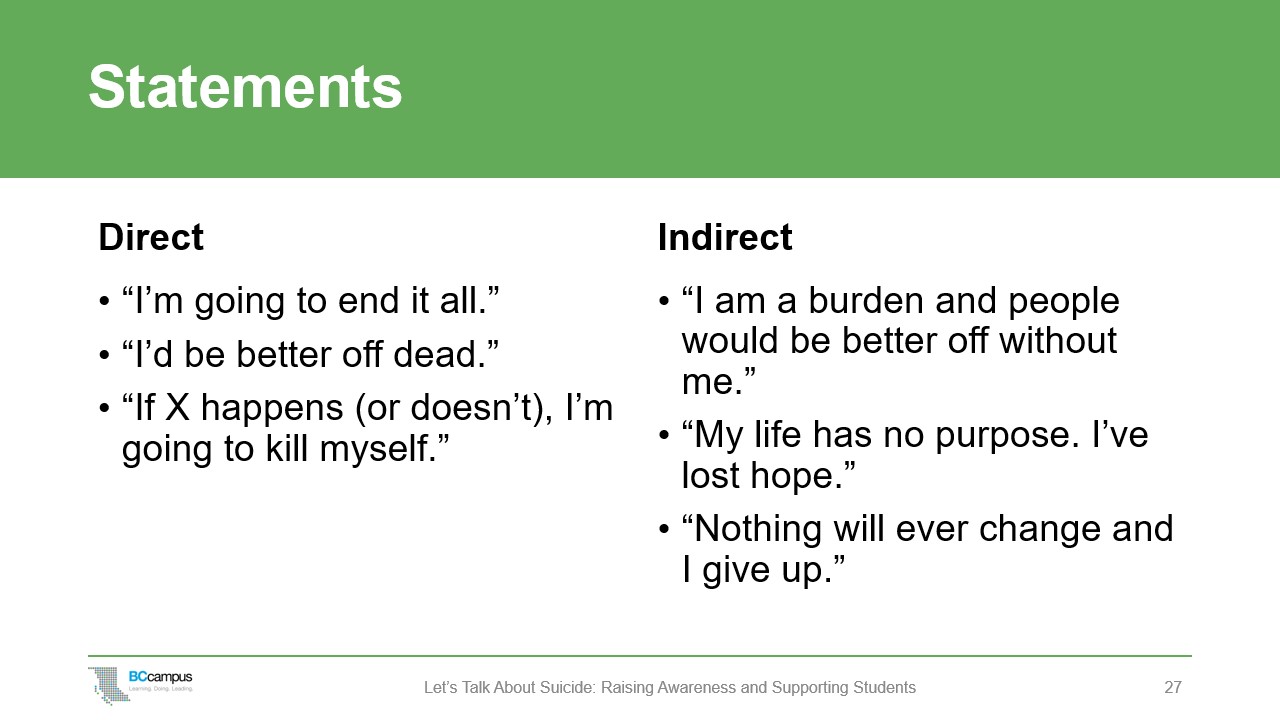

Sometimes a person will make statements about their intention.

Direct statements could be:

Indirect statements could be:

What physical signs might indicate someone is contemplating suicide?

A person’s actions can be a sign that they are considering suicide. Any of the following actions could be a warning sign:

Ask the group: What stressful events would likely contribute to a person contemplating suicide?

Write down people’s answers, which may include:

The two most common themes are:

Suicide Contagion

Suicide contagion, or copycat suicide, refers to the increase in suicide-related behaviour as a result of inappropriate exposure to or messaging about suicide. There is evidence to show that copycat suicides do occur under some circumstances. If someone is already vulnerable (depressed, anxious, isolated, has previously attempted suicide, or is showing other warning signs), one suicide can trigger another.

Suicide contagion is most pronounced when someone loses someone close to them. Youth appear to be especially vulnerable. Other conditions that can increase the risk of suicide contagion are high-profile, sensational portrayals of suicide in the media, or inadvertent glorification of a suicide victim. Providing safe and appropriate information about suicide helps to start positive dialogue and reduce the stigma associated with suicide.

Sometimes a person doesn’t give any signs that they are having suicidal thoughts before they end their life. This is a very difficult and painful thing to deal with. It brings us back to the importance of resiliency, self-care, and supporting each other.

However, there are things we can do. The next section looks at how we can respond to and support someone who may be thinking of suicide.

9

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/suicideawareness/?p=96

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

If you observe clues that lead you to suspect someone may be suicidal, it is important that you check it out in more detail.

It can be difficult to acknowledge clues that seem to indicate that a person you know may be planning to kill themselves. But it can be tragic to disregard them.

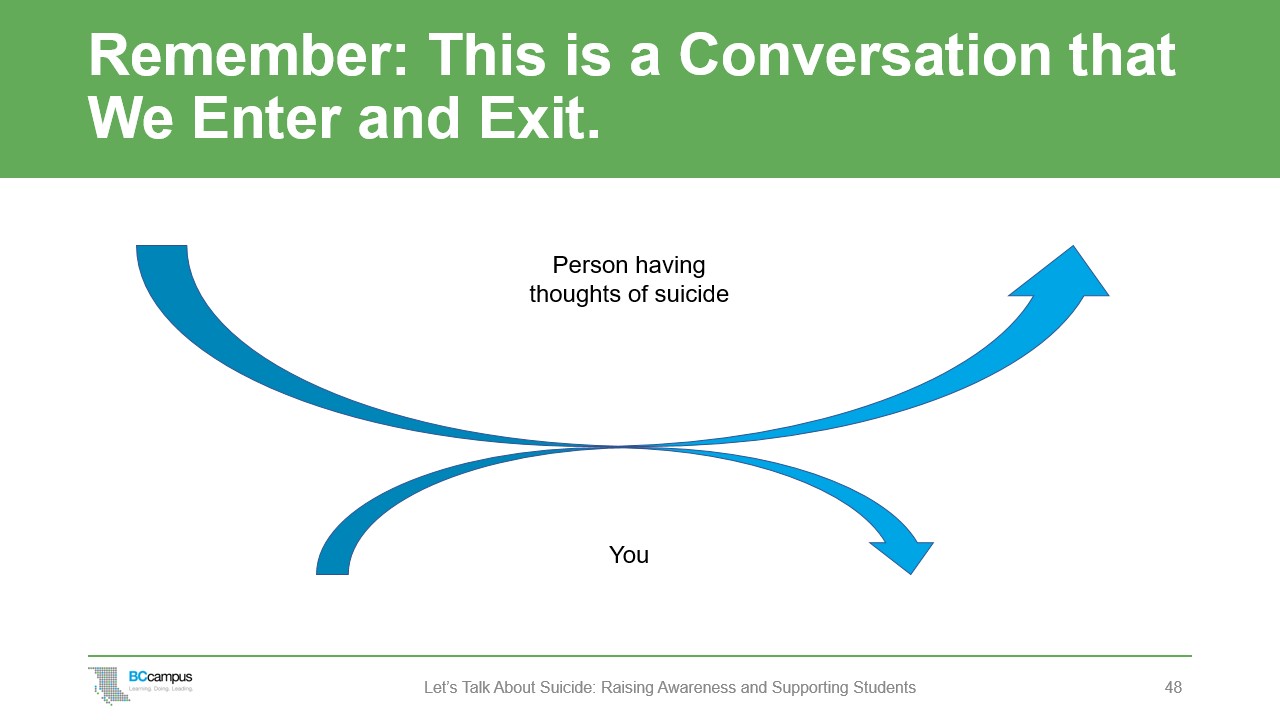

The main thing that people need is to be heard and not judged. The most effective intervention you can do is to listen with empathy and be non-judgmental.

Let the person know you hear them, believe them, and understand their distress as best you can. Tell them that you will help connect them to appropriate resources.

It does not have to be a lengthy conversation. Sometimes a conversation and a referral can be made within 10 minutes. What is most important is that the conversation is based on active listening and care. Sometimes just a few genuine words of concern and understanding can make a big difference and help get a person to connect with a counsellor or the best person to help them. You can’t take away their pain or solve their problems. But you can care.

There are no magic words. Be yourself. If you are concerned, your voice and manner will show it. Be patient, calm, accepting. This is more important than having the perfect words.

You may think that it’s all just talk and wonder how that’s going to help, but asking a person and having them talk about how they feel greatly reduces feelings of isolation and distress. Simply talking about their problems for a length of time will give a suicidal person relief from loneliness and pent-up feelings. They become aware that another person cares, and this can give them a feeling of being understood. A conversation can take the edge off their agitated state, and it may help them get through a bad night.

Communicate your concern for their well-being by offering to listen. Good listening is more than just listening quietly. It means demonstrating that you can be supportive without being judgmental. It means accepting their feelings as the truth for the person, no matter how irrational they might appear to you. It means that you are comfortable enough with your own feelings to set them aside and listen to theirs.

To demonstrate how to respond in a helpful, compassionate way, you could show a short video from well-known sociologist Brené Brown: Brené Brown on Empathy. The BCcampus resource Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students’ Mental Health and Wellness has more information on developing empathetic listening skills if you want to explore empathy more with your group.

Here are some ways you can introduce the signs that you notice:

These questions can start a conversation with someone you are concerned about, and this is also just normal empathic human interaction. You can check things out without it being a scary conversation. The goal is to practise asking about things you have noticed and to probe and listen for other warning signs.

You could start with:

You could then ask directly: “Are you feeling so bad that you’re considering suicide?”

Or:

Other ways to ask about suicide:

Scenario Walk-Through

To help help participants think about how they would talk to a student they’re concerned about, you could read the scenario out to them and then have a discussion about the best way to respond to the student.

Scenario

A student is facing final exams and says to you, “It’s no use. I’ll never be able to pull this off.” As the student speaks, they hardly seem to stop to draw breath. The student tells you they have a voice in their head that is always criticizing and saying they are worthless.

This student also mentions that they can’t concentrate or focus. They feel like they are failing and just can’t get back on track. They don’t see the point in continuing and say, “It’s not going to matter much longer anyway.”

How would you respond?

Key points

A possible response could be:

If the student refuses, you could say, Another option is for us to call the crisis line together right now so you can talk with them and find out about some resources.

If the student says no, you could say, I care about you and am worried about you, so for me to feel comfortable, I need to have someone contact you to see how you’re doing and help support you.

If the person says they are not thinking of suicide, accept their response. You’ve shown you are ready, willing, and able to engage in a serious conversation.

When a person says no, they usually will explain why not:

They may say they have stronger reasons for living and usually are reluctant and have concerns about the effect on others they care about. Listen supportively and offer resources as necessary.

If a person says they are thinking about suicide:

The goal is to keep the other person safe. Now is not the time to solve all problems.

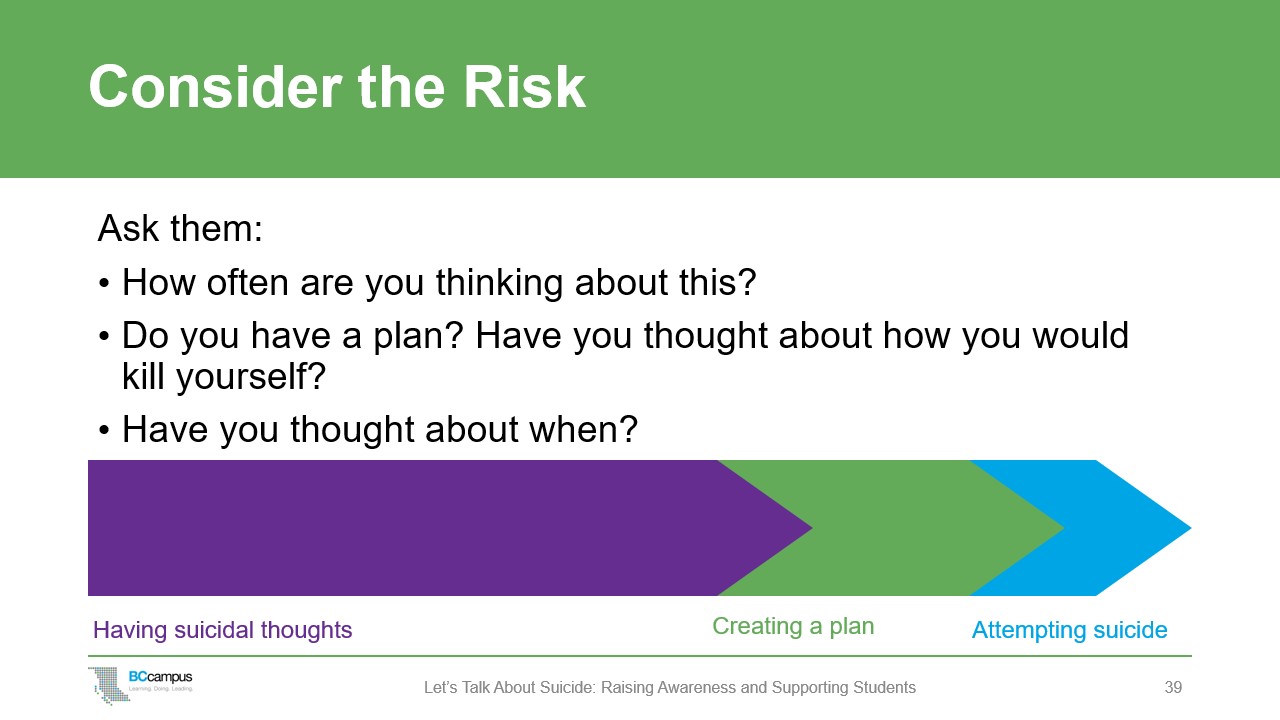

If a person says they are thinking of suicide, you need to consider the risk. Ask them:

By asking these questions, you can get a sense of how serious they are. The more prepared they are, the greater the risk.

It is similar to taking a trip and the preparations a person makes before the trip. How serious is this person about the trip? Are they just talking about wanting to take the trip or have they started looking into trip destinations? Or are they really prepared for the trip and have already booked their flight and started packing their bags?

More often than not, people do not have a plan for suicide, but if the plan is immediate, if steps have already been taken (pills, self-harm), or if a conversation is not possible, call 911 and stay with them until help arrives.

What to Keep in Mind When Talking About Suicide

The most appropriate way to raise the subject will differ according to the situation, and what the people involved feel comfortable with.

When having a conversation about suicide, you want to:

10

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/suicideawareness/?p=113

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Preparing for the Session.

When talking to a student in distress, you will want to look for a natural point in the conversation to mention resources.

To introduce the idea of a referral, you could say:

If it is not an emergency situation, you can refer the student to supports on campus. There may be a list with services and contact information for these services at your institution. If not, Handout 1 is a fillable PDF that has space to add in contact information for key supports. Below are some of the services available at most campuses:

If the student is not on campus, you can connect with these services and ask that they connect with the student by telephone or video.

Support for Marginalized Groups

When a person has a sense of belonging and connectedness with family, friends, culture, and community, they are less likely to take their own life. Unfortunately, not all students have this sense of belonging, and some students, such as Indigenous students, international students, students with disabilities, and LGBTQ2S+ students, are at a higher risk of isolation and may not have the support they need.

There are a number of provincial crisis lines that offer support. Here are some key ones:

If you haven’t already passed out Handout 1: Quick Reference: Responding to Students in Crisis, share handout out now so participants have a sheet with referral information.

If You’re Concerned for a Student’s Immediate Safety

If it’s an emergency situation, such as the student has taken pills, is experiencing psychosis, or is a danger to themselves or others, call 911 and then contact campus security (if the student is on campus). If the student is not on campus, call 911 and tell the operator the student’s current location as soon as possible.

If it’s not an emergency, but you are concerned, it can be helpful to offer to contact support services on the student’s behalf while they are with you. You may also offer to walk with the student to counselling services.

When you are unsure what to do, consult with your colleagues, chairs, deans, or others whom you trust. Counsellors can meet with staff and faculty who are concerned about a student and are unsure how to handle the situation. You can also call a crisis line if you have serious concerns about a student. You are encouraged to consult when:

Sometimes a student may not want to see a counsellor or refuses help.

Your first step in these cases will be to consider safety: Is anyone at risk of immediate harm, whether it’s the student or someone else? If so, share your concerns with a counsellor or someone who can help ensure safety. If a student expresses thoughts about suicide, you don’t have to carry that knowledge alone or assess the risk yourself – consult, refer, and if the risk is imminent, then contact emergency services.

If there is no risk of harm to anyone, keep in mind that ultimately it is the individual’s right to choose whether to seek help. Individuals are resilient and often come to their own solutions or find their own supports when they are ready.

Ensure you are supported! Talk to friends, family, other instructors, an Elder, or a counsellor to share your concerns and decide how to proceed.

Please be aware that if you refer a student to counselling services and are hoping to follow up to find out about the student, it is up to the student to give consent to release information.

Unless a student gives permission, faculty and staff won’t be notified of what has happened.

Responding on Social Media

This session focuses primarily on face-to-face communication, but many departments have social media accounts, and it’s possible a student may reach out to faculty or staff through social media or post a comment on a department’s social media. If a student says anything on social media that makes you think they may be suicidal, take the threat seriously. Treat people online the same way you would treat them in person.

If the person is in imminent danger, contact 911 and give whatever information you have.

If something still doesn’t feel right consult with your supervisor/chair/dean, student centre, campus security, or campus resources.

Remember: the most important thing you can do is listen and help connect the person to resources. Knowing that someone cares and that there is help available is what helps people recover.

Having a sense of purpose, hope, belonging, and meaning are essential to recovery.

People who are considering suicide have lost hope, and they need to be reminded that there is hope. Some hopeful messages for people who have thoughts of suicide:

When you are supporting someone, remember:

IV

11

In this section, you’ll find examples of scenarios you can use, either in person or online, to provide opportunities for participants to practise using the knowledge they’ve gained.

These scenarios provide helpful tips on what to say to students in different situations. If you don’t have time for practice and discussion, try to allow some time to briefly review some of the responses. You can provide the scenarios as a handout or PDF (see Handout 2: Talking About Suicide: Scenarios and Responses).

ACTIVITY: Scenarios

Ask participants to work in pairs to talk through some possible things to say to the student. Give the participants one of the five scenarios provided below to discuss together.

Working in pairs, you can either role-play or discuss together how you might respond and offer support to the student in this scenario. This is a chance to think through how to express your care and concern for the student and offer support and any further resources that seem appropriate. It is also an opportunity to practise asking the question: Are you thinking about suicide? It is a difficult question to ask and having a chance to say it out loud and practise will help build confidence.

Questions to discuss as a group:

How did people respond? Debrief with the large group.

Online

If your video-conferencing software allows you to create breakout rooms, you can have people work together in smaller groups in breakout rooms to discuss the scenarios. You could share the scenarios in the chat and then assign each group to read a specific one to discuss. Alternatively, you could move from room to room and verbally provide the scenario.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://opentextbc.ca/suicideawareness/?p=116

A student is facing final exams and says to you, “It’s no use. I’ll never be able to pull this off.” As the student speaks, they hardly seem to stop to draw breath, and you notice that they are fidgeting and having a hard time sitting still. The student tells you they have a very critical voice in their head that is always criticizing and saying they are worthless. This student also mentions that their focus and concentration are quite poor. They feel like they are failing and just can’t get back on track. They don’t see the point in continuing and say, “It’s not going to matter much longer anyway.”

I can see that you’re upset about the exams. I can hear the fear in your voice and understand your worries about what will happen. When you say, “It’s not going to matter much longer anyway,” I wonder if you mean you are thinking about suicide? I want to support you to be safe and to have a good outcome from this challenging time. I wonder if you’d be willing to talk to a counsellor? It’s confidential and I think it’s a wise thing to do. I’d like to walk over there with you.

If the student refuses, you could say, Another option is for us to call the crisis line together right now so you can talk with them and find out about some resources.

If the student says no, you could say, I care about you and am worried about you, so for me to feel comfortable, I need to have someone contact you to see how you’re doing and help support you.

A mature Indigenous student comes into your office upset. They disclose to you that a close relative has just died by suicide, and they are overwhelmed with mixed feelings of grief and helplessness. They want to be home with their family and community, but they also have upcoming projects due in many of their courses. They express feelings of hopelessness and say, “I don’t think I can cope with this. I think it would be easier to just end it.”

I’m so sorry to hear about your loss; dealing with the grief from someone dying can be difficult, particularly so when they died by suicide. I can see this has been very troubling for you. Thank you for confiding this to me.

When you say, “It would be easier to just end it,” do you mean you’re thinking of suicide? We have counselling services on campus that are confidential and free for all students. Can I walk you down to their office so you can meet them and see if it would be a good fit to talk with one of their team? You are going through a tremendously difficult time and should be proud of yourself for seeking support.

Are there any cultural supports here that I can assist you in connecting with? Have you spoken with the staff in Indigenous services? I can introduce you to the staff there if you don’t already know them. I think they’ll be really receptive to supporting you and might have community or cultural supports that you can use.

A student who has disclosed to you in the past that they are transgender approaches you in tears. When you ask what is happening, they tell you that they were home with their family over the holiday break and they came out to their family. Their family’s response was not supportive, and the student tells you their parents made hurtful and derogatory comments during the discussion. The student makes statements like “This is so difficult. I can’t keep going like this” and “I don’t know why I even try anymore; my own parents don’t love me or accept me for who I am” and “I’m tired of having to validate myself and who I am.” They share other more general feelings of loneliness and hopelessness.

Thank you for sharing this with me. I can appreciate this is such a difficult time for you and this has a significant impact on your well-being. While I don’t personally know what it’s like to identify with the LGBTQ2S+ community and not have the support or acceptance of your family, I can appreciate that this is a fundamentally important aspect of your well-being. Do you have any ideas on how I might be able to support you through this? Have you connected with our pride centre or student union office on campus? I am happy to walk you over there now if you would like.

I have heard you make some statements about feeling hopeless and losing a sense of purpose in your life generally. Are you having any thoughts of suicide? We have counselling services on campus that are confidential and free for all students; can I walk you down to their office so you can meet them and see if it would be a good fit to talk with one of their team?

If the student says no, you could say Another option is for us to call the crisis line together right now so you can talk with them and find out about some resources. I want you to know that I support you; you’re a valued and important member of our campus community. I’d like to support you in any way that I can to know that you are seen, valued, and celebrated here on campus.

You noticed a student in class who has been wearing the same clothes on a few occasions and looks somewhat dishevelled. They appear tense at times and other times they’ve seemed sleepy in class. Last class you walked by them and wondered if you smelled alcohol. They have been handing in their assignments but doing mediocre, and their grades have been dropping. The most recent assignment wasn’t handed in. You feel concerned that the student may be suicidal but you’re not sure.