Ronnie Hawkins

- Summarise the diverse manifestations of global anthropogenic environmental change that characterise the Anthropocene.

- Explain how those changes affect nonhumans and ecosystems, creating the sixth mass extinction event in the Earth’s history.

- Describe what characteristics and circumstances render an animal species particularly at risk of becoming extinct in the Anthropocene.

- Explain what food webs are, giving examples; explain how they can become ‘frayed’ by human impact.

- Summarise how marine food webs are affected by acidification, deoxygenation and marine heat waves.

- Differentiate the impacts exerted on food webs by macroplastics, microplastics and nanoplastics.

- Summarise the challenges that render global overpopulation particularly problematic and difficult to address.

- Explain how population size, consumption level, technological means work together to determine the ecological impact of a person.

- Analyse how cultural factors conspire to render patterns of mass consumption to become part of the War on Nature.

- Explore how the assumptions, beliefs and aspirations held by neoclassical economic theorists render their field non-scientific.

- Develop a personal view about justifications, critiques, prospects of humanity’s War Against Nature.

This chapter is made up of the ‘case studies’ that follow from Our War Against Nature, written from a perspective that sees human security as co-extensive with maintaining the integrity of the Biosphere; in other words, if the Biosphere goes down we go down. It is important for us to resist the ‘shifting baselines’ phenomenon, a tendency to adjust uncritically to ‘the new normal’ as ecosystems are disrupted, human-altered landscapes spread and the global climate shifts into new extremes. Instead of recapping the dynamics of climate change, discussed in Chapter 9, however, the focus here will be on some of the pressing but lesser known “other” problems our growing demand on planetary systems is generating, with connections to climate change pointed out where pertinent. Many of the articles referred to herein have appeared in the scientific literature just in the last five years, and public awakening to the stark reality of our “existential crisis” is considerably more recent. It may not yet be too late to prevent a ‘state shift’ of the Earth System and the massive loss of Holocene-adapted lifeforms likely to accompany it, but the case studies presented in Part I of this chapter are meant to stand as evidence that our current trajectory is accelerating toward such a shift. Appreciating the magnitude of our human footprint, examined in Part II, should help us to understand what sorts of moves are needed to change course; it will require transformation of many of our humanly constructed institutions and certain widely shared beliefs and values–but that’s well within our capacity as flexible biological beings. We face a choice between clinging to the habits of thought and behavior that have driven Our War Against Nature and creating new ways of living that will assure a viable future for all Life on Earth. What will we choose?

Chapter Overview

PART I: The Assault on Organisms and Ecosystems

12.1 Introduction: Welcome to the Anthropocene!

12.2 Animal Armageddon

12.3 The Fraying of Food Webs

12.3.1 Terrestrial Food Webs: Defaunation and Pollution

12.3.2 Marine Food Webs: Overfishing, Disruption and Collapse

12.4 Assault on the Oceans: Chemical and Physical Changes

12.4.1 Acidification, Deoxygenation and Marine Heat Waves

12.4.1.1 Ocean Acidification and Decalcification of Shelled Marine Life

12.4.1.2 Ocean Deoxygenation

12.4.1.3 Marine Heat Waves

12.4.2 Plastic, Microplastic and Nanoparticulate Pollution

12.4.2.1 Macroplastics

12.4.2.2 Microplastics

12.4.2.3 Nanoparticulates

PART II: The Human Footprint

12.5 The Human Footprint: Population

12.6 The Human Footprint: Consumption

12.6.1 Sustaining the Human Population

12.6.2 The Global Livestock Industry

12.6.2.1 The Diet-Environment-Human Health-Animal Ethics Quadrilemma

12.6.2.2 The Deforestation of the Amazon

12.6.3 The “Bushmeat” Crisis

12.6.3.1 Consuming Our Evolutionary Cohorts

12.6.3.2 Profiting from Body Parts

12.7 Money Games: Chasing the Symbol

12.8 Who Are We?

Resources and References

Key Points

Extension Activities & Further Research

List of Terms

References

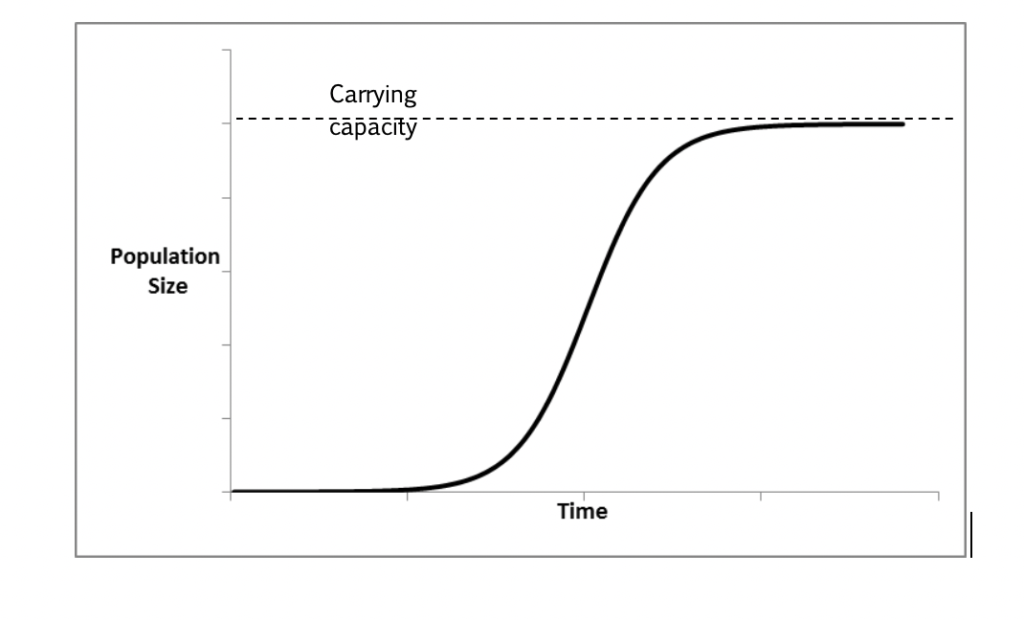

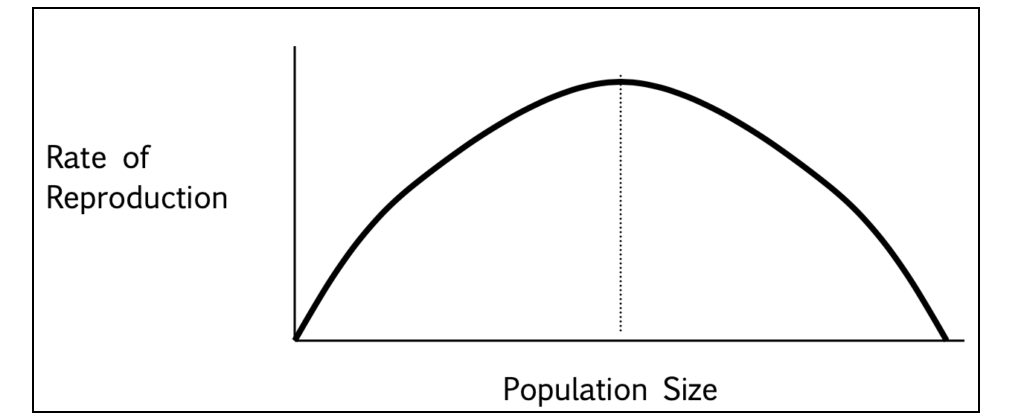

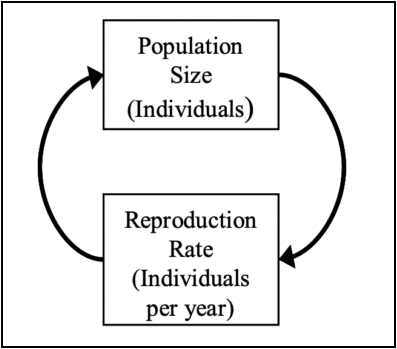

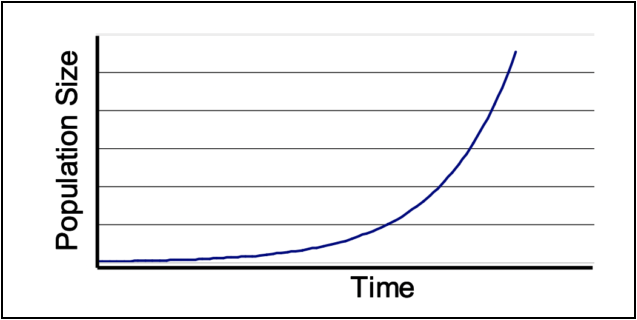

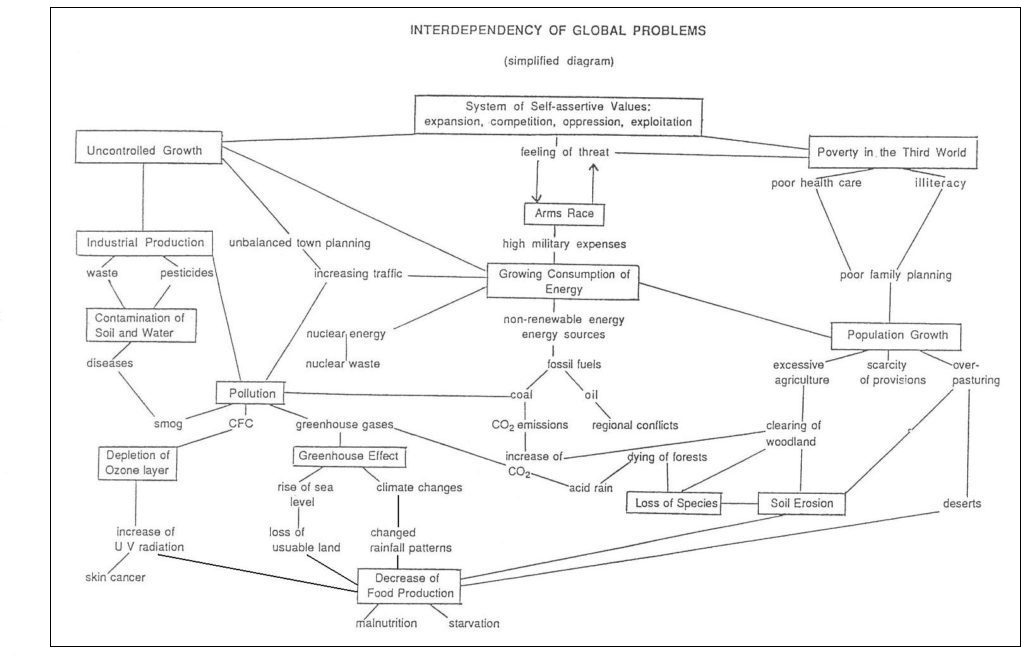

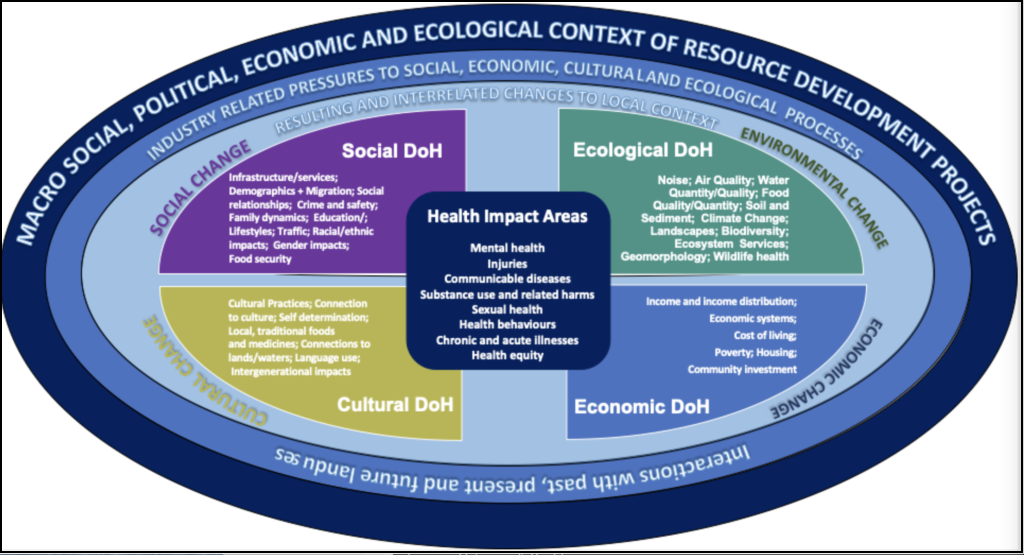

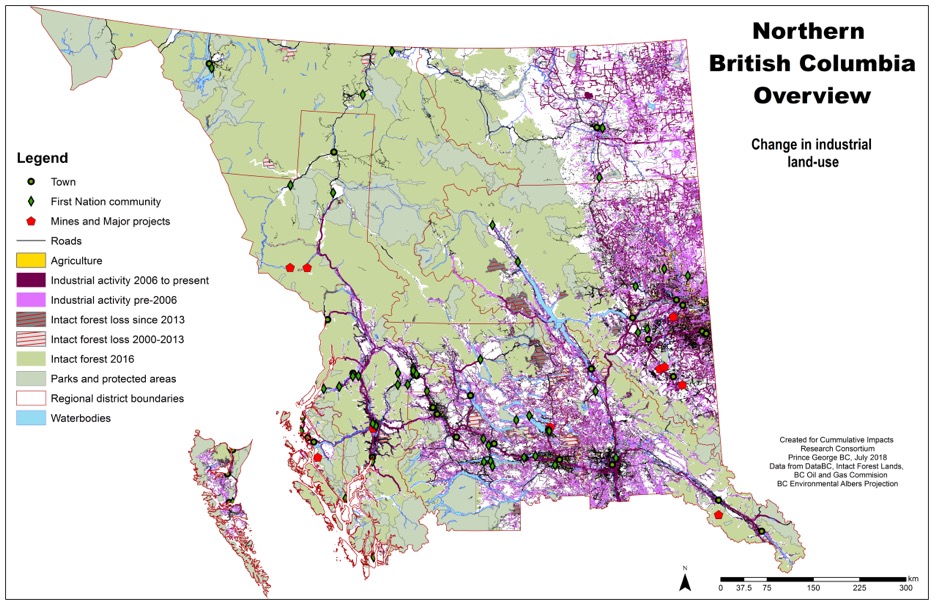

We humans have become so numerous and so powerful, the changes we have wrought on the Earth’s surface so extreme, that a new geological epoch is being named after us, the Anthropocene. It seems we have left the stability of the Holocene epoch, the preceding 10,000 to 12,000 years that followed the last Ice Age, and are now entering a period wherein many planetary parameters are shifting toward values unseen in hundreds of thousands or millions of years, with unknown consequences not only for human civilization but for all highly evolved lifeforms. Paul Crutzen dates its onset to the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s, heralded by the invention of the steam engine and, coincidently, the beginning of the anthropogenic increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide and methane (Crutzen, 2002). Representative of the emerging field of Earth System Science, Will Steffen and colleagues (2011) present a series of graphs, all reflecting the general outline of a J-curve, starting out slowly and rising to very high values rapidly near the end — the paradigm case being our human population, holding at less than one billion for all our previous existence prior to 1800 and then beginning a slow rise followed by a sharp upturn around 1950, coinciding with the onset of the “Great Acceleration” of “just about everything” else, from motor vehicles, telephones and McDonald’s restaurants to water use, fertilizer consumption, and species extinctions — and attempt to consider the effects of the changes in all these variables and their interactions with one another on the state of the biogeophysical system as a whole. Johan Rockstrom and associates (2009) delineate nine planetary boundaries that must not be crossed if we are to stay within “a safe operating space for humanity,” of which three have already been exceeded: rate of biodiversity loss, climate change, and interference with the nitrogen cycle, primarily in the form of massive amounts of reactive nitrogen created in the manufacture of fertilizer. Anthony Barnosky and co-authors (2012), meanwhile, focus specifically on the possibility of a “planetary-scale tipping point” that could trigger an irreversible shift from the present state of the Earth System into another, largely unknown one. As they explain, “biological ‘states’ are neither steady nor in equilibrium; rather, they are characterized by a defined range of deviations from a mean condition over a prescribed period of time,” and from time to time this “mean condition” can change, either as the result of a “sledgehammer” effect, such as the sudden bulldozing of an ecosystem, or via a “threshold” effect, through the accumulation of incremental changes over time, the actual threshold being unknown to us before the shift occurs. These authors list the global-scale “forcings” pushing us away from our present state, including habitat transformation, energy production and consumption, and climate change — all of which “far exceed,” in rate and magnitude, the forcings that drove the last global-scale state shift, the transition from the last ice age into the Holocene epoch, a transition that occurred over more than 3,000 years. They note, however, that “human population growth and per-capita consumption rate underlie all of the other present drivers of global change,” and so these ultimate drivers of Earth System change will be considered in more detail later in this chapter.

Steffen and colleagues (2018) recently explored the “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene,” depicting the “limit cycle” traced by the Earth when it was following its glacial-interglacial oscillation and, since many parameters are now departing from earlier values, projecting a possible alternative path that reaches a state they term “Hothouse Earth,” the impacts of which “would likely be massive, sometimes abrupt, and undoubtedly disruptive.” Analyzing the Anthropocene “from a complex systems perspective,” they illustrate our present precarious position, perched upon a “stability landscape” between two stable states, by asking the reader to visualize a marble rolling along a ridge between two valleys, representing two different “basins of attraction”–complex interactions among various parameters can trap the system in either of these two different states, should something trigger its rolling down into one or the other valley. While feedbacks in the complex relationships among many variables (greenhouse gas concentrations, ice sheet reflectivity, etc) have kept us in the relatively stable Holocene “valley” for thousands of years, anthropogenic changes are lifting us out of that valley and could potentially push us over the “hilltop” into another, possibly quite different and most likely less hospitable basin of attraction, which they describe as a “geologically long-lived, generally warmer state of the Earth System.”

To avoid the “Hothouse Earth” scenario, they stress the need for “planetary stewardship,” including “resilience-building strategies” to keep the planetary system in a “Stabilized Earth” state, noting that the current trends of our collective human activities, which tend to focus on enhancing economic efficiency rather than biogeophysical stability, “will likely not be adequate” for doing so. Carl Folke (2016) advocates seeing our human societies coupled with natural processes as interdependent social-ecological systems that need to focus on developing resilience, “the capacity to change in order to sustain identity” by “reorganizing in the face of disturbance.” He explains, “adaptation refers to human actions that sustain development on current pathways, while transformation is about shifting development into other emergent pathways and even creating new ones.” Engaging in “resilience thinking” in confrontation with our planetary boundaries, it becomes obvious that a transformation of our collective human actions is required, so as to become “in tune with the resilience of the biosphere” (2016). However, as he and his colleagues remark, “alas, resilience of behavioral patterns in society is notoriously large and a serious impediment for preventing loss of Earth System resilience” (Folke et al., 2010). Perhaps propagating awareness of the ontological difference between our socially constructed economic and political institutions and the complex systems that sustain the Biosphere — which we did not create and which we destabilize at our peril — could help foster such a transformation.

“At least 1 million plant and animal species of the estimated eight million known are now at risk of extinction,” summarizes Eric Stokstad (2019) of the report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity (IPBES) issued in May of 2019. The report follows an announcement by the Living Planet Report the previous fall, informing us of “an overall decline of 60% in the population sizes of vertebrates between 1970 and 2014 — an average drop of well over half in less than 50 years” (World Wildlife Fund, 2018). And it was followed by another shocker, a report that nearly 3 billion birds — representing almost a third of bird abundance in North America — have been “lost” from ecosystems over the last 48 years (Rosenberg et al., 2019). The recent news of how severely our collective human activities have impacted other lifeforms on this planet has been a rude awakening for many of us, but alas, a dip into the recent scientific literature assures us that it is true.

On a scientifically conservative estimate, we humans have already brought about the extinction of almost 500 species of vertebrate animals since 1900 (Ceballos et al., 2015); these scientists found that “the evidence is incontrovertible that recent extinction rates are unprecedented in human history and highly unusual in Earth’s history,” leading them to conclude that “our global society has started to destroy species of other organisms at an accelerating rate, initiating a mass extinction episode unparalleled for 65 million years.” The total number of species already declared officially extinct may not sound that alarming, however, until the number of species, vertebrate and invertebrate, that are now considered to be somewhere along the way — officially “threatened” with extinction in the near future — is revealed: it was around 28,000 in 2019 — 27% of over 100,000 assessed species–and includes, for example, 25% of all mammals, 14% of all birds, and 40% of all amphibians (IUCN Red List, 2019). The “1 million at risk of extinction” reflects the fact that more than 500,000 terrestrial species now “have insufficient habitat for long-term survival” and thus “are committed to extinction,” many of them within the coming decades unless significant habitat restoration is carried out and other threats defused quickly (Diaz et al., 2019, p. 13).

High levels of vertebrate population decline and loss are found across the tropics, and are especially prominent in the Amazon, central Africa and south/southeast Asia. The ‘proximate’ drivers of the descent toward extinction — the immediate threats responsible for taking out a species — include overexploitation (direct killing by humans), habitat destruction through land conversion and fragmentation, invasion by introduced species and disease, toxification from pesticides and other pollution, and now, increasingly, climate change (Dirzo et al., 2014). The “ultimate” drivers of these trends, however, are just about always some combination of continuing human population growth and increasing per capita consumption (Ceballos et al., 2017). Overexploitation of wildlife now takes the form of the ‘bushmeat’ trade — now including the taking of animal body parts to sell on the world market — in many tropical countries around the world, as what may have once been the ‘sustainable’ hunting of wild animals for meat has “metamorphosed into a global hunting crisis” that now threatens “the immediate survival” of over 300 species of mammals as well as other kinds of wildlife (see Ripple et al., 2016a), a problem that will be considered in more detail in Section 12.6.3.

Focusing on extinction per se is misleading, however, because it obscures the fact that an actual extinction is usually the result of a long period of loss of organisms from local populations and loss of populations from the landscape that eventually adds up to the disappearance of the species altogether. While extinction results in a permanent loss of biodiversity from the planet, moreover, population declines and alterations in species composition contribute to alterations in ecosystem function that can cascade throughout ecosystems in nonlinear fashion (as will be discussed in the following section). In 2017, Gerardo Ceballos, Paul Ehrlich and Rudolfo Dirzo reported on the “biological annihilation” that’s happening with increasing rapidity now, as numbers of individual animals shrink and populations diminish. Examining data for a sample of over 27,000 species of terrestrial vertebrates — nearly half of known vertebrate species — they found that around a third are experiencing significant population losses, both in numbers and in range size; moreover, almost half of the 177 species of mammals they examined have lost more than 80% of their geographical ranges since 1900, and all of them have lost at least a third. Most shocking of all, however, is their estimate that “as much as 50% of the number of [vertebrate] animal individuals that once shared Earth with us are already gone” (Ceballos et al., 2017). And a look at biomass ratios really brings home the massive scale of our growing human footprint, and what it is doing to our evolutionary cohorts within the Biosphere. Yinon Bar-On, Rob Phillips, and Ron Milo (2018) estimated the total biomass of all living wild mammals (terrestrial and marine) today to be, in round numbers, only about 0.006 gigatonnes of carbon (GtC), while the biomass of all the humans on the planet — more than 7 and a half billion of us–is .06 GtC, and that of all livestock (dominated by cattle and pigs) is 0.10 GtC; in other words, the total biomass of all the wild mammals on Earth is equal to only about four percent of the total biomass of humans plus their domesticated food animals. When the biomass of great whales and other marine mammals is excluded, moreover, the biomass of wild land mammals is estimated to be about 0.003 GtC, or about five percent of the biomass of humans alone, and less than two percent of the biomass of us humans and our livestock taken together. The impact of our human species on other forms of life has thus been truly staggering.

Characteristics that tend to make a species more vulnerable to diminution and eventual extinction include large body size, low reproductive rate and large home range requirements, especially when the existing habitat range is small, making many of the “terrestrial megafauna” severely threatened (see Ripple et al., 2016b, 2017). You can take almost any large-bodied wild mammal you’ve ever heard of and chart an ominous decline. Franck Courchamp and colleagues (2018) discovered that there is still very little public awareness of the dire straits of many of their favorite animals; recapping the little-known situation with our “charismatic megafauna,” tigers have been knocked down to less than seven percent of their historical levels in the wild, lions to less than eight percent, and elephants less than 10%; three of four giraffe species have experienced declines of over 50%, one more than 90%, leopards have lost up to 75% of their range, with only three percent of the original range remaining for six of nine subspecies, and cheetahs have been extirpated from 29 African countries, remaining on only nine percent of their historic range, while two gorilla subspecies have dwindled to a few hundred individuals and populations of the other two have plummeted to less than half what they were over the last 20 years.

While habitat loss has been steadily reducing populations across the board, these authors report that, when killing for bushmeat, trophy hunting and conflicts with humans are considered together, direct killing by humans is responsible for the greatest number of them being endangered overall; they estimate, for example, that “unsustainable bushmeat hunting, trophy hunting, habitat loss and human conflict all combine to make most of African lion populations surviving the next few decades unlikely” (Courchamp et al., 2018, S2). Elephants and rhinos are being slaughtered mercilessly for their ivory and their horns across Africa, and even giraffes, which have declined by 40% over the last 20 years, are in part falling prey to the trade in their highly prized tail (see Chase et al., 2016; Gibbens, 2018; and Daley, 2016, respectively). Polar bears, who typically support themselves almost exclusively by preying on seal pups emerging from crevices in the sea ice, and as the ice thins and melts, they will inexorably starve unless they learn to consume land-based prey (Whiteman, 2018). Killer whales, once abundant in the oceans, are now estimated to count only in the tens of thousands, with many populations declining as a result of a reduction in salmon and other prey, disturbance by boat traffic, acoustic injury from sonar used in naval exercises and underwater exploration, and toxic effects of oil spills and other pollution; more than half of their populations are thought to be at high risk of “complete collapse” over the next century from the bioaccumulation of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in their tissues (Desforges et al., 2018).

Among our closest evolutionary relatives, 60% of primate species are threatened with extinction “because of unsustainable human activities,” while 75% of primate populations are decreasing globally (Estrada et al., 2017). Chimpanzees are officially classified as “endangered,” and all gorillas are now listed as “critically endangered,” while the tiny mountain gorilla population is holding on at less than 500 individuals (Gray, 2013). Bonobos are also classified as “endangered,” with an estimated population of 15,000 to 20,000 individuals (Fruth et al., 2016); disturbingly, their entire range is contained within the lowland forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa and one that is subject to out-of-control slaughtering of wildlife for “bushmeat,” as well as increasing habitat fragmentation, warfare, and the rages of an ebola epidemic, to which great apes are susceptible. Meanwhile, the fourth great ape, the orangutan, may be hurtling toward extinction the fastest of all, with over 100,000 killed in Borneo between 1999 and 2015, cutting the population by more than half, leaving an estimated 70,000-100,000 there plus less than 14,000 in Sumatra; all orangutans are now listed as “critically endangered,” by expanding palm oil plantations as well as hunting in primary and selectively logged forests (Voigt et al., 2018).

Pangolins — a little-known, shy, nocturnal mammal described as resembling “an artichoke on legs” that, when threatened, rolls itself up in a scale-covered ball sufficient to protect it from all natural predators but not, unfortunately, from its human enemies — are being devastated by a burgeoning trade in their meat, skin and scales; after China’s population of pangolins was reduced by 94% since the 1960s, poaching of pangolins in Africa has reportedly increased by 150%, with as many as three million now being removed annually from Central African forests, most of them bound for China (Ingram, 2018); pangolins are being considered a “probable animal source” of the coronavirus outbreak that has now become a global pandemic (Cyranoski 2020); Sonia Shah points out that many zoonoses now affecting the human species are the result of our accelerating invasion of natural habitats for live animals and their parts to sell in so-called “wet markets” (Shah, 2020), as will be discussed further in section 12.6.3.

Hundreds of thousands of seabirds suffer high mortality as “incidental catch” in drift nets, purse seines, gill nets, traps, trawls and longlines, while wind turbines have been estimated to kill more than 400,000 birds a year, communication towers over six million, and domestic cats between 1 and 4 billion in the US alone (White, 2013), even as millions are being shot while migrating over Europe “for food, profit, sport, and general amusement” (Franzen, 2013; Margalida & Mateo, 2019). Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of wading birds have been destroyed by the closing off of the Saemangeum tidal flat by South Korea in 2006, described by Michael McCarthy (2015, pp. 66-68, 81) as “the biggest destruction of an estuary that has ever taken place,” “a giant engineering vanity project” and “one of the most egregious examples of environmental vandalism the modern world can offer”; the number of shorebirds using the flat are down by as much as 97% (Lee et al., 2018), and worse yet, 50 million wading birds using the East Asia/Australasia Flyway for their twice-yearly migration are at risk from escalating habitat destruction all along the Chinese and Korean coast of the Yellow Sea, their precipitously declining numbers already indicating “a flyway under threat” (Piersma et al., 2016). The Helmeted Hornbill, another notable bird species, was put on the “Critically Endangered” list in 2015, not only for rapidly dwindling habitat but also because demand is growing for the “red ivory” of its “casque,” which is carved into handicrafts for Chinese markets, something that was recently decried in the journal Science (Li & Huang, 2020). And, unbeknownst to many ardent admirers of Irene Pepperberg’s late Alex, the celebrated African Grey Parrot is also now in danger of extinction. African Greys used to inhabit more than a million square miles across West and Central Africa, but because of the international pet trade — the African Grey is the single most heavily traded wild bird, according to CITES, the organization that regulates global wildlife trade — it is believed that more than a million of the birds were taken from the wild over the past 20 years. Ghana reportedly has lost 90-99% of its African Greys since 1992 (Annorbah, 2015); as populations are wiped out in Ghana, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and elsewhere, birders are recognizing “the African silence” (Steyn, 2016).

Reptiles are included in the global decline, while amphibians are seriously threatened worldwide by the chytridiomycosis panzootic that is affecting over 500 species, causing the presumed extinction of at least 90 of them over the past half-century, the greatest loss of biodiversity attributable to a disease ever recorded (Scheele et al., 2019). Large fish in the oceans have reportedly dropped in numbers by over 90% (Myers and Worm 2003, SeaWeb 2003), with some species, such as cod and some tunas, falling by as much as 99%, and it has been noted that only 37% of shark species are not threatened with extinction, with up to 100 million sharks being killed every year for the global trade in shark fins, the major driver of their road to extinction (Sadovy de Mitcheson et al., 2018). And populations of mobulid rays–manta and devils rays, now known to be highly social and intelligent but also very slow to reproduce, with only one offspring every three years or so — are plunging, largely due to the growing Chinese market for their gill plates, erroneously believed to “clean impurities” when ingested but actually containing high levels of cadmium and arsenic (Guardian, 2014). They are also suffer high mortality as “incidental catch” in drift nets, purse seines, and other technologies of industrial fishing.

The dire straits of many more of our fellow members of the Biosphere could be recounted here, but perhaps it is more pertinent to ask how it is that even the well-known mammals — the ‘charismatic megafauna’ so prominent in our human imaginations — could be under such assault without it having come to our global attention long before this. How could we have missed it? This question is explored by Franck Courchamp and his colleagues (2018). They identified “the 10 most charismatic animals”: the tiger, the lion, the elephant, the giraffe, the leopard, the panda, the cheetah, the polar bear, the gray wolf and the gorilla, all but one of which are either vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered, and discovered, that fully half of people asked in surveys were not informed about their conservation status. Volunteers were then asked to document every encounter with one of these 10 animals in advertisements, entertainment, logos and so on, and they reported seeing as many as 30 individual images of each of the 10 species over the course of a week, corresponding to several hundred encounters per month; lions, for example, were seen at an average rate of 4.4 images per day, “meaning that people see an average two to three times as many ‘virtual’ lions in a single year than the total population of wild lions currently living in the whole of West Africa.” They concluded that “the public perception of the conservation status of these species appears to reflect virtual populations rather than real ones” (Courchamp et al., 2018), masking the real extinction risk, and they have proposed that companies benefiting from using images of these (and other endangered) animals in their marketing pay a fee to be spent directly on conservation efforts benefiting these animals. But, meanwhile, our War Against Nature continues to take its heavy toll.

12.3.1 Terrestrial Food Webs: Defaunation and Pollution

It is now known that “ecosystems are built around interaction webs within which every species potentially can influence many other species,” and that the “trophic downgrading” that results from the loss of large apex consumers reduces food chain length and can lead to abrupt state changes in ecosystems “with radically different patterns and pathways of energy and material flux and sequestration” (Estes et al., 2011). Anthropocene defaunation is a more precise name for the phenomenon discussed in the previous section, since the term defaunation can cover loss of individuals, populations, and species of wildlife (Dirzo et al., 2014); it is a term that needs to become as widely recognized as deforestation, since “a forest can be destroyed from within as well as from without” (Redford, 1992), as will be discussed in more detail in Section 12.6.3. Human hunting is increasingly taking a toll, especially on the larger animals, while other proximate drivers of overall terrestrial defaunation include habitat destruction, the invasion of nonnative species and climate change.

Large-bodied animals that feed at the ‘apex’ of trophic pyramids, like the great cats and other true carnivores, often exert strong top-down regulatory effects on the ecosystems they inhabit (see Ripple et al,. 2014), so the loss of a carnivore at the highest trophic level can “cascade” down through all the trophic levels in an ecosystem. When sea otters were removed from waters off the coast of Alaska, sea urchins, released from otter predation, devastated kelp beds, until they themselves were ‘fished out’ from many parts of the ocean (see Steneck, 2002); likewise, when dam construction in Venezuela created a chain of predator-free islands, leaf-eaters–howler monkeys, iguanas and leaf-cutter ants — were released from predation and there was a subsequent reduction in young canopy trees (Terborgh et al., 2001). Conversely, when an apex predator, the grey wolf, was reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park, wolf territories reduced elk grazing pressure on young aspen stands, allowing the forest to regrow and ultimately changing the landscape in a remarkable manner (see Ripple & Beschta, 2011). Large herbivores like bison and elephants are also important components of ecosystems, acting as “ecosystem engineers” by trampling and consuming vegetation (Ripple et al., 2015); they can also be important seed dispersers, and as herbivore populations become depleted around the world, a “wave of recruitment failures” is expected among animal-dispersed trees. While not typically apex consumers, primates are important seed dispersers as well, as are fruit-eating and nectar-feeding bats and many kinds of birds, which are also important in pollination and insect control.

Meanwhile, so far nothing has been said about invertebrate life — “the little things that run the world,” as E. O. Wilson called them more than 30 years ago, when the current situation was barely imaginable; even then, however, he expressed doubt “that the human species could last more than a few months” if they all disappeared (Wilson, 1987). Now several recent studies are highlighting alarming trends. Hallman and colleagues (2017), counting insects in nature reserves surrounded by agricultural fields within a typical Western European landscape, reported a decline in the biomass of flying insects of about 80% over 30 years — an average loss of 2.8% biomass per year that, if continued, could result in a total loss within the century. A parallel decline was observed in larks, swallows, swifts and other insectivorous birds, leading one of the researchers to comment, “if you’re an insect-eating bird” living in the areas studied, “four-fifths of your food is gone in the last quarter-century, which is staggering” (see Vogel, 2017). A similar 60-80% drop in biomass over 36 years was recorded for insects living in the tree canopy of a tropical forest, as well as a 98% drop in insects from the forest floor (Lister & Garcia, 2018), with “synchronous declines” documented in the lizards, frogs and birds dependent upon them for food.

Reviewing of more than 70 reports of insect decline from around the globe, Sanchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys (2019) compiled evidence of “dramatic rates of decline” in insect numbers that, if continued, they projected could “lead to the extinction of 40% of the world’s insect species over the next few decades.” More recently, Seibold and colleagues (2019) reported “widespread declines in arthropod biomass, abundance, and the number of species across trophic levels” in both grassland and forest habitats, finding the major drivers of the declines to be largely associated with agriculture at the landscape level. “Our study confirms that insect decline is real,” Seibold told BBC News, noting that it is occurring in protected areas as well as those that are intensively managed (Briggs 2019). A group of conservation biologists “deeply concerned about the decline of insect populations worldwide” provided a comprehensive overview of the problem and issued a “scientists’ warning to humanity” about the seriousness of this problem as this chapter was undergoing its final edit (Cardoso et al., 2020).

Since insects are adapted to a very narrow range of temperature variation in the tropics, climate warming may be a factor in insect decline there, but elsewhere the “root cause” of the dramatic decline is thought to be the intensification of agriculture and, in particular, “the widespread, relentless use of synthetic pesticides,” according to Sanchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys (2019). As the most widely used insecticides in the world, neonicotinoid insecticides are highly suspect as a major driver of this decline. They are systemic, meaning that they are absorbed and distributed to all parts of the plants they are applied to, not only leaves and flowers but pollen and nectar. They persist in soils for a year or more, but are water soluble, contaminating up to 80% of surface waters; there they affect a variety of aquatic insect larvae, indirectly reducing populations of fish, frogs, birds, bats and others that feed on them. Along with fipronil, the neonicotinoids are suspected of playing a large role in the decline of honeybees, bumblebees and other wild bees around the world (Sanchez-Bayo, 2014); foraging bees typically take contaminated pollen and nectar back to the hive, where sublethal effects of these neurotoxic insecticides affect movement, olfaction, orientation, and navigation, impairing the mushroom bodies (see Section 11.3.5) important in bees’ learning and memory, disturbing foraging and homing behavior and disrupting the “waggle dance” used to communicate the location of nectar plants to other bees in the colony (van der Sluijs et al. 2013). These synthetic insecticides disrupt biological controls and trigger pest resistance, and they don’t really contribute to crop yields, according to Sanchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys, so there will be “no danger” in reducing their use drastically (2019).

Meanwhile, the escalating use of herbicides–especially glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup, widely used around the world now in combination with genetically modified crops — is leading to growing concerns about their effects on soil invertebrates, as well as soil microorganisms, the functioning of below-ground ecological communities, and the aquatic communities downstream of agricultural runoff. According to Benbrook (2016), about 8.6 billion kg have been applied worldwide over the last 40 years, with dramatic increases over the last decade or so. Glyphosate acts by inhibiting the EPSPS enzyme in the shikimate pathway, essential to metabolism in plants, fungi, and some bacteria but absent in vertebrate animals, so it was originally assumed to pose minimal risks, but a potentially serious effect on honeybees has recently been reported, illustrating the complexity of ecological systems: genomes of the beneficial bacteria in honeybee gut flora contain the gene coding for EPSPS, potentially making them susceptible to glyphosate inhibition, possibly increasing mortality and reducing their effectiveness as pollinators around agricultural fields (Motta, Raymann & Moran, 2018).

Glyphosate is absorbed from the leaves of sprayed plants and transported systemically to the roots; it can be released into the rhizosphere, possibly being transferred through the roots of dying plants to living, untreated ones, affecting trees and other plants near treated fields. Kremer and Means (2009) found glyphosate interacted with the below-ground microbial community, and Kremer (2014) reported herbicide-resistant weed infestations release root exudates potentially detrimental to the mycorrhizal fungi, important for plant uptake of nutrients and water. A review article by Annett, Habibi and Hontela (2014) examines the reported effects of glyphosate and formulations with different surfactants on organisms in freshwater ecosystems, noting amphibians seem particularly susceptible to its toxic effects due to their larval dependence on water and frequent location near agricultural fields. There are also growing concerns about its effects on human health, especially since high residue levels are being found on crops subjected to post-season drying (“green burndown”) with glyphosate (Myers et al., 2016); studies on residues, and the concept of “substantial equivalency,” have been criticized as inadequate (Cuhra, 2015). In 2015, the World Health Organization found “sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in experimental animals” and “limited evidence of carcinogenicity in humans for non-Hodgkins lymphoma” following exposure to glyphosate (WHO, 2015).

Predictably, more than 200 weed species have developed resistance to one or more herbicides, with at least 24 of them resistant to glyphosate (Heap, 2013). In response, biotechnology companies are developing second-generation, “stacked” GM crops with resistance to several herbicides, typically 2,4-D and dicamba, containing synthetic auxins that interfere with the natural plant hormones involved in growth regulation; they are reportedly of low toxicity to vertebrates but extremely toxic to broadleaf plants, and their high volatility and proneness to drift risks injury to both non-GM crops and nontarget plant species, according to Mortensen and colleagues (2012). Noting that the evolution of resistance to both herbicides and insecticides is outstripping our ability to come up with new ones, Gould, Brown and Kuzma (2018) discuss why we “mostly continue to use pesticides as if resistance is a temporary issue,” calling it a “wicked problem” arising from a combination of social, economic and biological factors that decrease incentives for taking a different approach to “pest” control.

According to Hayes and Hansen (2017), “there is probably no place on earth that is not affected by pesticides; they report that an estimated 2.3 billion kilograms of pesticides are being used annually around the world, and they review evidence of alterations in landscapes, populations and gene pools of organisms from both actute toxic and chronic “low dose” effects. Many older, “legacy chemicals” are also still around, contaminating food webs around the world (Matthiessen, Wheeler & Weltje, 2018). The organochlorine insecticides, “hard” pesticides like DDT, were banned in most developed countries years ago but are still in widespread use, with 3.3 million kilograms produced annually (Hayes & Hansen, 2017); these, along with other chemicals such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), are known as persistent organic pollutants (POPs)– long-lived, fat-soluble compounds that are known to accumulate in animal tissues and biomagnify, increasing in concentration as they move up food chains, often reaching very high levels in apex predators. Many of the POPs have been shown to be toxic, endocrine-disrupting and/or carcinogenic, and long-lived vertebrates occupying high trophic levels not only risk such effects from retaining these chemicals in their own bodies for long periods of time but potentially pass them on to offspring in eggs or milk (Rowe 2008). Kohler and Triebskorn have drawn attention to how little we know about the full extent of unintended impacts of pesticides on wildlife at the higher levels of populations, communities and ecosystems (2013); immunosuppression reportedly can be caused by all the organochlorine, organophosphate, and carbamate insecticides as well as by atrazine and 2, 4-D herbicides.

Moreover, in addition to the biocides — chemicals intentionally designed to kill certain forms of life, the “pesticides” that include rodenticides, insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, and so on — there are over 4000 pharmaceuticals now in global use in human and veterinary medicine continuously being released into the environment through wastewater and sewage sludge; they are generally highly potent at low concentrations, and their modes of action show strong evolutionary conservation across vertebrate species–meaning that what affects us will probably affect many other lifeforms somewhat similarly. An Australian team found over 60 pharmaceutical compounds in the bodies of invertebrates collected from streams and in riparian spiders consuming them, considering them likely to be contaminating other consumers such as frogs, birds and bats (Richmond et al., 2018); they calculated that vertebrate predators on aquatic invertebrates such as the platypus could consume as much as half a human’s therapeutic dose of antidepressants, kilogram for kilogram.

Finally, it should be noted that pollution from small particles of plastic — “microplastics” — which is a growing concern in the world’s oceans, to be discussed in section 12.4.4, is problem for terrestrial ecosystems as well. A recent study found that microplastics are being carried by the wind to places far from population centers and are likely distributed widely around the planet; daily counts of atmospheric deposition averaging almost 250 fragments 3 mm or less in size per square meter were found in a remote and supposedly “pristine” mountain area of the French Pyrenees (Allen et al., 2019). “It suggests that this is a far bigger problem than we have currently thought about,” says one of the study’s co-authors; the concern is that it “gives us a background level of microplastic that you probably get pretty much everywhere in the world” (see Thompson, 2019). If there are worries about this atmospheric deposition contaminating soil, however, here’s an even bigger source of that problem: some farmers use treated sewage sludge to fertilize their fields, adding a load of microfibers skimmed off of wastewater along with the nutrients that could add up to tens to hundreds of thousands of tonnes of plastics added to farmlands in Europe and North America every year (Thompson, 2018a); yet another soil additive, moreover, is so-called “mixed waste — a ground-up amalgam of food scraps and unrecyclable material” that, applied thickly on one farm in Australia, added so much plastic to the topsoil that it looked like it was “glistening.” And yes, it’s finally happened — “anthropogenic debris” has been reported in beer, as well as sea salt and tap water (Kosuth, Mason & Wattenberg, 2018). It seems microplastics are now everywhere — they have even been found in human feces (Parker, 2018).

12.3.2 Marine Food Webs: Overfishing, Disruption and Collapse

Ransom Myers and Boris Worm startled the scientific community with their announcement (2003; see SeaWeb, 2003) that “the global ocean has lost 90% of large predatory fishes,” along with “general, pronounced declines of entire communities across widely varying ecosystems.” The decrease in many marine vertebrates has been severe enough that too few of them remain to carry out their normal functional role in many ecosystems, in some places leaving “empty estuaries” and “empty reefs” similar to the “empty forests” in terrestrial systems (McCauley et al., 2015). The striking marine defaunation is recent, since fishing effort intensified only over the last century with the arrival of industrial fishing techniques, the loss of fish being followed by a decline in sea turtles, sea birds, and marine mammals. As Crespo and Dunn (2017) summarize, “the world’s oceans are experiencing an unprecedented level of biotic exploitation, which is altering the abundance and population structure of many species, transforming the composition of biological communities, and threatening the integrity and resilience of entire marine ecosystems.” Marine biologist Daniel Pauly and colleagues explain (1998) that fisheries around the world have shown a pattern over recent decades of “fishing down the food web,” where what is caught is transitioning from “long-lived, high trophic level, piscivorous bottom fish toward short-lived, low trophic level invertebrates and planktivorous pelagic fish,” often with complete collapse of the high trophic level species and replacement with lower trophic level species in fishing catches.

Changes in Chesapeake Bay illustrate how these changes evolved in one coastal community. According to Jackson et al. (2001), “gray whales, dolphins, manatees, river otters, sea turtles, alligators, giant sturgeon, sheepshead, sharks and rays were all once abundant inhabitants of Chesapeake Bay but are now virtually eliminated.” Until the end of the 19th century, the Bay contained dense concentrations of oysters, filter feeders that consumed phytoplankton so efficiently that algae blooms never occurred, even with agricultural runoff. Introduction of mechanical harvesting in the late 1800s had a serious impact on the oyster reefs by the early 20th century and decimated them by the 1920s. Eutrophication began to be observed in the Bay by the 1930s. Today, with the oyster reefs essentially destroyed, Chesapeake Bay is now considered a “bacterially dominated ecosystem,” with a trophic structure completely different from what it was a century ago; it is characterized by “population explosions of microbes responsible for increasing eutrophication,” and, in combination with hypoxia, disease, and continued dredging, this now prevents the recovery of oysters and their associated ecological community (Jackson et al., 2001).

Coral reefs are in decline around the world due to global warming-induced coral bleaching, and the combination of higher temperatures and increasing acidification of ocean waters as they absorb CO2 may at some point drive them over a ‘tipping point’ into algae-dominated states; according to Hoegh-Guldberg et al. (2007), at atmospheric CO2 levels nearing 500 ppm, “reefs will become rapidly eroding rubble banks, as are already seen in parts of the Great Barrier Reef.” Australia’s Great Barrier Reef — the world’s largest and most diverse coral reef ecosystem–has undergone mass bleaching events four times over the last twenty years, the northern two thirds being severely damaged by the last two in 2016 and 2017, with the concomitant heat stress killing many reproductive adult corals, leading to nearly a 90% drop in larvae recruited into the population in 2018 (Hughes et al., 2019). Many reefs are also suffering from overfishing, with loss of the larger predatory fish cascading through the system, allowing the escape of smaller fishes and invertebrates that causes booms and busts of algal overgrazing, such that “today, the most degraded reefs are little more than rubble, seaweed, and slime”; these researchers also report that many reefs off the coast of Florida are “well over halfway toward ecological extinction” (Pandolfi et al., 2005).

Perhaps the best-known example of marine defaunation, however, is the ‘crash’ of the Northern Atlantic cod fishery off Newfoundland and Labrador in 1992, which apparently came as quite a surprise to the fishery operators and regulators. Atlantic cod had been harvested for centuries, but with modern harvesting equipment and factory ships arriving in the 1950s, catches went from around 227-327,000 tonnes per year to a peak of 735,000 tonnes in 1968 and then began to diminish, and were down by 80% by 1977. Harvesting was then restricted, but the cod never recovered to anywhere near their previous levels; technological advances in locating and capturing fish allowed increasing catch sizes despite “dramatic declines in catch rate,” concealing the true condition of the cod population throughout the 1980s until its sudden collapse (Hutchings & Myers, 1994). The cod still haven’t come back significantly, and cascading effects within the marine ecosystem have allowed small pelagic fish like herring that principally feed upon zooplankton — which include the eggs and larvae of the cod– increased in biomass by around 900%, effecting a “predator-prey role reversal” that may be largely responsible for preventing cod recovery (Frank et al., 2005; Frank et al., 2013).

Tunas are another group of particular concern. More than 60% of the tuna harvest is captured in purse seines, giant nets that pull up from below to encircle entire schools of tuna and other schooling fish once they are located with sophisticated sensing technologies, taking a significant amount of ‘bycatch,’ other species that are (usually) unintentionally caught up in the seine nets, such that “tuna fisheries are directly responsible for endangering a wide range of oceanic pelagic sharks, billfishes, seabirds, and turtles” (Juan-Jorda et al., 2011) as well as marine mammals, killing around 1000 dolphins a year and harming many more (see Brown, 2016). Unlike the cod, overall tuna catches have continued to increase since the 1950s, but this continuing increase “was achieved by halving global tuna biomass in half a century” (Juan-Jorda et al., 2011). Tunas and their relatives, along with the billfish — swordfish and marlins–are apex predators of pelagic food webs, so they very likely exert important trophic effects within the whole ocean ecosystem; unfortunately, some of them are highly valued economically and thereby increasingly threatened with extinction, with the biomass of the Southern Bluefin tuna is now said to be about five percent of its original size, so its population “has already essentially crashed,” paralleling the trend of the western Atlantic Bluefin, whose population has not rebuilt since it plummeted in the 1970s (Colette et al., 2011). Individual Bluefin tunas were selling at over $100,000 five years ago, making them among the “rhinos of the ocean” — for those of a certain mindset, they will “never be too rare to be hunted” (McCauley et al., 2015).

And it is clear all is not well with marine fisheries globally. Daniel Pauly, attempting to reconstruct the historical sizes of fish populations, concluded that most of his colleagues had fallen prey to the “shifting baselines syndrome,” whereby each new generation of scientists takes the stock sizes that prevailed at the beginning of their careers as the ‘baseline’ and evaluates changes in relation to it, not noticing that the baseline itself has been gradually shifting downward (Pauly, 1995), a phenomenon he has described in a (2010) TED talk. In a recent interview (Schiffman, 2018), Pauly called the global industrial fishing industry “a Ponzi scheme,” explaining, “a Ponzi scheme is where you pay your old investors money from new investors, not from any actual profit.” That’s what’s been happening as industrial fisheries have developed over the last 50 or 60 years, he charges — “we fish out one place, European or North American waters, for example, then we go to Southeast Asia or Africa, now even Antarctica.” With the new technologies that have become available, “we’ve destroyed all the protections that fish populations once enjoyed” — “depth was a protection, cold was a protection, ice was a protection because we couldn’t fish in those areas” — but “we can now go everywhere the fish once sheltered.” Global catches have been declining by one to two million tonnes a year since the mid-1990s, he reports; we’re getting up against the limits of the Earth now, it seems, and when you run out of new fishing stocks to exploit, “the whole [Ponzi] scheme collapses.”

But what’s happening to populations of deep-sea organisms may be cause for even more concern. Most deep-sea fisheries utilize bottom trawls, fishing gear that drags a net along the ocean floor and that can weigh several tonnes and do tremendous damage to the benthic habitat. One study found that, compared with the impacts of oil and gas drilling, submarine communications cables, marine scientific research, and the historical dumping of radioactive wastes, munitions and chemical weapons, “the extent of bottom trawling is very significant and, even on the lowest possible estimates, is an order of magnitude greater than the total extent of all the other activities” (Benn et al., 2010). Moreover, bottom trawling activities can be concentrated on ocean ridges and seamounts, which are particularly vulnerable to the effects of such disturbance. Seamounts are “true mountains under the sea,” usually 2-3 kilometers in height, that have become covered with sessile invertebrates including octocorals, hard corals, sponges, crinoids, and other suspension feeders that structure the habitat for fish but that are very fragile and easily broken (Watling & Auster, 2017). Daniel Pauly tries to describe what was “encountered” by a trawler in his “shifting baselines” TED talk: “Well,” he says, at the time “we didn’t have words for it,” but now he knows, “it was the bottom of the sea”; 90% of the catch was made up of sponges and other organisms that had been attached to the bottom, while any fish that were caught were just “little spots on the piles of debris.” The “most rational decision,” according to Watling and Auster, is to simply protect seamounts in perpetuity; meanwhile, Pauly advocates closing off the “high seas” — the open ocean outside the control of the coastal countries, which extends out to 200 miles offshore — from fishing, allowing many fish populations to rebuild and very likely increasing the harvestable catch of many less-developed coastal nations, while Eileen Crist has called for declaring the whole “area” of the high seas off limits to all extractive activity, for fish and fossil fuels as well as for minerals, renaming it “the common heritage of all Life” (Crist, 2019).

12.4.1 Acidification, Deoxygenation and Marine Heat Waves

As we humans have changed the chemistry of the atmosphere by emitting increasing amounts of carbon dioxide and other gases, we have also been changing the chemical composition and physical properties of the world’s oceans. Three major changes in the oceans are taking place globally in response to this: acidification, deoxygenation and an overall warming trend with focal areas of markedly higher temperatures than were the recent norm, all of which have ominous implications for the organisms that live there.

12.4.1.1 Ocean Acidification and the Decalcification of Shelled Marine Life

Only about half of the carbon dioxide we have emitted over recent decades has remained in the atmosphere; of the other half, about 30% has been absorbed and stored in the oceans and 20% incorporated into the bodies of terrestrial biota, holding down the amount of global temperature rise that would otherwise have occurred (Feely et al., 2004). When CO2 dissolves in seawater it forms carbonic acid, which releases hydrogen ions, making the water slightly less alkaline and more acidic. Acidity or alkalinity is measured in pH, a logarithmic scale on which 7.0 indicates neutrality. Ocean acidification doesn’t mean that the seas are “turning acid” — they are slightly alkaline, presently with a pH of 8.6 — but rather that their pH is moving downwards, toward the acid side of the scale. Ocean acidification should perhaps be called ocean decalcification, however, because the most sinister effect of reducing the availability of carbonate ions in the oceans is that it will make it harder for many different types of shelled organisms to form the calcium carbonate that mineralizes them and, if carbon emissions continue to rise as they have been, this will threaten the survival of a large percentage of the organisms making up the base of oceanic food webs, with ramifications that will reverberate throughout marine ecosystems (Hardt & Safina, 2008).

Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) can crystallize in three different forms, each with a different solubility; it takes the form of aragonite in corals and pteropods as well as many larger molluscs, as magnesian calcite in coralline algae, and as calcite in coccolithophores and foraminifera. Aragonite and magnesian calcite are about 50% more soluble than calcite, so the organisms utilizing these forms are likely to be the most vulnerable in the near future. A combination of temperature, pressure and depth determine whether or not the ocean water is saturated with the calcium ion, Ca++, a state in which the mineral will tend to be deposited, or undersaturated, in which it will tend to dissolve; a definite horizontal boundary, known as the saturation horizon, exists at a certain depth for each crystalline form, below which the shells and other calcified parts of the bodies of these marine organisms will start to dissolve, according to the following reaction:

CO2 + CaCO3 + H2O → 2HCO3− + Ca++

The saturation horizons for all these forms of calcium carbonate are becoming shallower by tens to hundreds of meters, squeezing calcifying marine organisms into an ever-shrinking available habitat between the saturation horizon and the surface (Hardt & Safina, 2008). Moreover, even in waters above the saturation horizon, as the degree of carbonate ion supersaturation decreases, the rate at which these animals are able to calcify their body parts decreases; nearly all reef-building corals are showing “a marked decline” in calcification under these conditions (Feely et al., 2004). A modeling study of calcium carbonate saturation under several emissions scenarios, “a new shallow aragonite saturation horizon emerges suddenly” in many places in the Southern Ocean between now and 2100 (Negrete-Garcia, 2019), potentially affecting shelled pteropods, cold-water corals, sea urchins, molluscs, coralline algae, and some foraminifera; this habitat contraction could occur as suddenly as within one year’s time, and occurred even under an emission-stabilizing scenario, just at a later time. “’That inevitability,” said one of the co-authors, Nicole Lovenduski, in an interview for the University of Colorado at Boulder (2019), “along with the lack of time for organisms to adapt, is most concerning.”

It is the rapidity of these anthropogenic changes, “potentially unparalleled” in the last 300 million years (Honisch et al., 2012), that has scientists extremely worried; “analog events” of relatively rapid CO2 release — but far less rapid than the one now underway–include the Paleocene-Ecocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) of 56 million years ago, which resulted in the largest extinction of deep-sea foraminifera in 75 million years, the Triassic-Jurassic (T-J) mass extinction of 200 million years ago, when CO2 levels doubled over 20,000 years, causing an almost total collapse of coral reefs, and the Permian-Triassic extinction of around 250 million years ago, the most severe extinction event since multicellular life evolved. An examination of the reef-building corals that survived the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) mass extinction of 66 million years ago and those that are presently classified as “of least concern” under the conditions being imposed by the mounting Anthropocene extinction event (Dishon et al., 2020) shows similar “survival” traits possessed by both groups, providing “alarming evidence that reef communities are currently in the process of transforming into disaster communities akin to previous extinction events.”

12.4.1.2 Ocean Deoxygenation

As if ocean acidification isn’t enough to worry about, our brave new Anthropocene is ushering in yet another grave concern: ocean deoxygenation — also a result of our unchecked emission of carbon, but in this case due to the ocean temperature increase it is causing. Many people are aware of the sudden “fish kills” that occur when a pulse of nitrogen- and phosphorus-enriched water, usually from agricultural runoff into surface waters and their outflow tracts, stimulates an algal bloom which then dies and decomposes, lowering the oxygen concentration in the water to a point that fish and other animals are unable to tolerate, but fewer are aware of the growing problem in the open oceans. The open ocean is believed to have lost about two percent of its dissolved oxygen since 1950, and has developed a number of “oxygen-minimum zones” (OMZs) that have expanded by millions of square kilometers over recent decades, now occupying a combined total area around the size of the European Union (see Breitburg et al., 2018).

Warming reduces the solubility of oxygen in water and increases stratification of ocean waters, reducing ventilation, the movement of oxygen from the surface into the interior of the ocean, and often limiting the input of nutrients as well, thereby reducing photosynthesis and thus the production of oxygen in the water. Moreover, just as the amount of oxygen available in seawater is decreasing, the metabolic processes of living organisms that consume oxygen are increasing with rising temperatures, putting the squeeze on many different types of marine life. Species vary in their oxygen requirements and their responses to low oxygen concentration, but alterations in their interactions, feeding habits, and therefore marine food webs are known to be occurring and expected to increase. Lowered oxygen concentration in the water column limits the extent of diel vertical migration, the movement of zooplankton and fish deeper into the ocean in the morning and toward the surface in the evening, compressing their available vertical habitat, reducing suitable habitat for deep-ocean organisms, and restricting some species to shallower waters where they are more vulnerable to predation and fishing pressure.

One of the most serious consequences of ocean deoxygenation is its potential to impair the vision of many marine organisms. The retina, containing photoreceptor cells, is the tissue with the highest metabolic demand in the bodies of terrestrial vertebrates, and hence of highest vulnerability; the need for oxygen is especially high in organisms with “fast” vision, where visual pigments need to regenerate rapidly, including not only fish but cephalopods like the octopus and squid and arthropods that depend on high-speed feeding and escape behavior, all of which may become subject to “visual hypoxia” after a much smaller drop in oxygen concentration than what would be metabolically limiting (McCormick & Levin, 2017). Hypoxia is also thought to be an important factor in the death of corals and their accompanying reef inhabitants. The evidence of increasing ocean deoxygenation as the climate warms is so alarming that a group of scientists and conservationists recently called for awareness of the problem to “extend to all facets of society, beyond the pages of scientific journals” (Earle et al., 2018), and the Kiel Declaration on Ocean Deoxygenation, calling for more marine and climate protection, was issued by over 300 scientists in September of 2018.

12.4.1.3 Marine Heat Waves

Another global-warming-related phenomenon that has recently emerged into common scientific parlance is the occurrence of “marine heat waves,” defined as strings of 5 or more days in which the ocean temperatures in a certain area are in the top 10% of temperatures recorded there over the past three decades. One such “marine heat wave” developed in the Gulf of Alaska in late 2013, a patch of exceptionally warm water a third the size of the continental United States that became nicknamed “the Blob” (see Cornwall, 2019). By the summer of 2015 it had doubled in size to over four million square kilometers, stretching from the waters off Baja California to the Aleutian Islands. with waters up to 2.5°C above normal. A little over a year later, marine food webs all along the western coast of North America were collapsing, with dozens of whales and tens of thousands of seabirds dying and more than 100 million Pacific cod suddenly vanishing.

The disaster apparently began with a ridge of high pressure that held winter storms at bay in the fall of 2013, reducing the effect of winds that usually brought deeper, colder water to the surface in the Gulf, and with them the nutrients the winds typically churn up, leading to a decline in the phytoplankton biomass. The decline in marine plant matter led to a decline in copepods and krill, zooplankton that formed the prey base for small forage fish like capelin and sand lance, which were staples for many seabirds. Only 166 humpback whales returned to Glacier Bay from their tropical calving grounds in the summer of 2015, down 30% from 2013, and all calves born that year were lost, while the bodies of 28 humpbacks and 17 finback whales subsequently washed up along the shoreline from Alaska to British Columbia. Thousands of young California sea lions were stranded on beaches when their mothers were forced to forage farther and farther from the shore in search of food, as many as half a million common murres died of starvation in early 2016, and the cod population dropped by 70% over 2015-2016, finally ‘crashing’ in 2017. It seems likely that what was being witnessed was a crumbling of the marine food web from the bottom upward.

The arrival of cooling La Nina winds at the end of 2016 finally broke the heat wave, stirring up the waters and reversing some of the effects of ‘the Blob.’ But by 2018, only two of five murre colonies seem to be returning to normal breeding levels; only 99 humpbacks returned to Glacier Bay, accompanied by only one calf; and cod numbers were projected to be even lower than the year before. There are some hopeful signs, with some rebounding of copepods and krill and with them forage fish and tiny cod, but the effects of this rebound will have to work their way up food chains. Meanwhile, marine heat waves are becoming more common, the number of days with a marine heat wave present somewhere around the globe having doubled since 1982. Without a major effort to slow down planetary warming, Blob-like temperatures could become typical for the northeast Pacific and perhaps elsewhere by 2050, pushing marine organisms and ecosystems to the limits of their defaunated, already-diminished resilience (Cornwall, 2019).

12.4.2 Plastic, Microplastic and Nanoparticulate Pollution

12.4.2.1 Macroplastics

The amount of plastic produced since 1950 now exceeds six billion tonnes (Chen, 2014), accelerating rapidly over the last decade; annual global production is now said to be around 320 million tonnes annually, with less than 10% ever recycled and about 40% of plastic waste resulting from single-use packaging (see Lavers et al., 2020); as a result of increasing production combined with inadequate ways of dealing with disposal, it is accumulating in the environment and persisting for long periods of time, entangling or blocking the digestive tracts of seabirds, marine mammals, sea turtles and many other species. As one example of a potential population-level impact, significant entrapment of hermit crabs was discovered in plastic debris, with as many as 500,000 crabs dying on the beaches of the uninhabited but “very polluted” Cocos Islands (Lavers et al., 2020); hermit crabs depend on shells retrieved from other animals, and are attracted to the odor of dead conspecifics, which helps them locate empty shells as they become available, but with the addition of this type of anthropogenic waste to their environment, “the very mechanism that evolved to ensure that hermit crabs could replace their shells has resulted in a lethal lure” — one single container was found to contain 526 dead and dying crabs. Since ingested plastic can potentially cause a variety of lethal and sublethal effects, ranging from the toxicity of its component monomers and plasticizers, chemical pollutants adsorbed to plastic surfaces, and micro- and nano-sized fragments interfering with nutrient absorption, entering living tissues, and accumulating at higher trophic levels in marine food webs, there has been a call to recognize plastic as a “persistent marine pollutant” like the persistent organic pollutants (POPs) whose production is largely phased out (Worm et al., 2017).

In round numbers, the amount of plastic washing into the ocean is somewhere between five and 20 million tonnes per year (see Lebreton et al., 2018); a portion of this is swept into the sea and may enter an oceanic gyre, a rotating circular current that traps it in an “accumulation zone” resembling a giant floating island. There are five major ocean gyres, circling in the North and South Pacific, North and South Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, each with its own floating patch of garbage, the North Pacific being the largest. The plastic that ends up in the ocean and along shorelines has to get there somehow, of course, and most of it comes down via riverine systems. According to Schmidt, Krauth, and Wagner (2017), 88% to 95% of all that plastic waste is thought to be coming from just 10 rivers; eight of these plastic-loaded rivers are in Asia and two in Africa, with the Yangtze River in China alone responsible for more than half of this waste stream, dumping an estimated 1.5 million tonnes into the Yellow Sea annually (for a comparison graphic, see Patel, 2019).

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) is a mass of largely plastic debris floating in a 1.6 million square kilometer area in the North Pacific Ocean off the coast of North America; it can be seen from the air, and is often pointed out by commercial pilots to interested passengers. Lebreton and colleagues (2018) estimated its total mass to be at least 79,000 tonnes; these scientists collected, classified and quantified the buoyant plastic pieces and particles composing it. Megaplastics, large pieces like fishing gear, were calculated to make up 42,000 tonnes; macroplastics, like crates and plastic bottles, 20,000 tonnes; mesoplastics, in the size range of bottle caps, 10,000 tonnes; and microplastics, 0.05-0.5 cm in diameter, 6,400 tonnes. The microplastics were generally fragments of larger plastic items, dispersed in an estimated 1.7 trillion pieces — in other words, microplastics made up around eight percent of the total mass, but 94% of the total number of pieces.

12.4.2.2 Microplastics

All of the mega-, meso-, and macroplastic pieces accumulating in the oceans are problematic enough, but the microplastic pieces and smaller ones have the scientists particularly worried; they are plastic particles less than 5mm in size (the size of “a grain of rice down to a virus”), generally formed as breakdown products of larger plastic pieces, and are now being discovered to be widely distributed in the air, water, and land around us (A. Thompson 2018a, 2018b, 2019). Extremely high concentrations of microplastic particles were recently found in Arctic sea ice by Ilka Peeken and colleagues (2018), and their findings suggest a larger circulation of them throughout the planet’s oceans, with the sea ice serving as a temporary sink; they speculate that large amounts of microplastics are likely to be released from sea ice as the Arctic meltdown accelerates. Fortunately, so far the concentration of microplastics in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica appears to be much lower, although their presence there at all indicates that marine plastic pollution is ubiquitous — “plastic-free ocean environments are increasingly rare” (Isobe, Uchiyama-Matsumoto & Tokai, 2017). There are disturbing indications that this accumulating mass of microplastics is entering marine food webs. Richard Thompson and colleagues reported finding microscopic plastic particle concentrations steadily increasing in collections of plankton samples dating from the 1960s through the 1990s; these authors demonstrated that microplastic particles were rapidly ingested by various components of marine food webs (R. Thompson et al., 2004). More recently, a group of researchers (Cozar et al., 2014) discovered a “gap” in the expected number of plastic fragments below a few millimeters in size, indicating what appears to be a massive loss of plastic from the surface of the open ocean; the size range of these “lost” plastic particles corresponds with that of zooplankton in the oceans, and plastic particles within this size range are commonly found in the stomachs of small, mesopelagic fish, the most abundant predators of zooplankton in the open ocean and in turn an important part of the prey base for upper trophic levels of the marine community. But perhaps the most serious threat is to the ocean’s large filter-feeders, including the “brainy” morbulids, manta rays and devil rays, as well as whale sharks and baleen whales (Germanov et al., 2018); supporting their large bodies on tiny zooplankton, they must swallow hundreds to thousands of cubic meters of seawater daily, and therefore must be taking in microplastics both directly from the water and indirectly from their contaminated prey. According to lead author Elitza Germanov, “It is vital to understand the effects of microplastic pollution on ocean giants, since nearly half of the morbulid rays, two thirds of filter-feeding sharks, and over one quarter of baleen whales are listed by the IUCN as globally threatened species and are prioritized for conservation” (see Gaworecki, 2018).

Revealing a major source of microplastic contamination in North America, a study of municipal wastewater treatment plant effluent from 17 facilities across the US found that, on average, each is releasing over four million microparticles per day, leading researchers to estimate that somewhere between 3 and 23 billion particles of microplastic are being released in US waterways through municipal wastewater per day overall (Mason et al., 2016), polluting lakes and rivers before making it into the oceans. High levels of microplastics, mostly in the form of fibers shed from synthetic fabrics, were also found in treated wastewater in Paris, as well as substantial levels in the River Seine (Dris et al., 2015). Not all microplastic particles that end up in rivers, lakes and oceans are from the breakdown of larger-sized pieces of plastic, however; many facial cleansers, cosmetics, toothpaste, and other personal care products contain intentionally produced plastic particles, most less than 1 millimeter in size, that escape wastewater treatment plants and can reach the oceans (Fendall & Sewall, 2009); one study estimated between 4,000 and 95,000 microbeads could be released in a single use of a facial scrub (Napper, 2015).

12.4.2.3 Nanoparticulates

If we don’t know much about what the microplastics are doing to our bodies, there’s an even bigger unknown out there: microplastics may eventually degrade all the way down into ‘nanoplastics,’ plastic pieces in the ‘nano’ size range of a few billionths of a meter, several millionths of the size of a “microparticle.” This is getting down to the size range of single atoms and molecules, and particles in this size range often have unusual properties that can be quite different from their properties in the larger size ranges, properties with largely unknown effects on living systems. So far, scientists have not found a good way to quantify the amount of nanoparticulate plastic in the oceans and surface waters, although they assume that, the smaller the particle, the more of them are going to be out there; they are just beginning to attempt assessing the effects that anthropogenic nanoparticulates have on living organisms, but they do know that particles this small can easily penetrate living tissues. Antarctic krill have been shown capable of ingesting microplastics (less than 5mm in diameter) and breaking them down into nanoplastics (less than 1 micrometer in size) through digestive fragmentation, a process possibly shared by other zooplankton (Dawson et al., 2018). The breakdown of larger pieces of plastic is not the only source of nanoparticulate contamination of aquatic and marine ecosystems, however; sunscreens containing engineered nanoparticles of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide are polluting beaches, with the potential to harm marine and aquatic organisms.

Dr. Jerome Labille discovered that almost 70 kilograms of sunblock cream was deposited at one small beach in the south of France visited by about 3000 people daily, amounting to more than 1.8 tonnes over the summer season, and releasing around almost 2 kg of titanium dioxide daily, or over 50 kg for the summer, much of it expected to accumulate on the littoral zone, affecting seaside wildlife of various kinds (AAAS Eurekalert! 17 Aug. 2018). Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide have long been used as sunblockers in traditional, ‘bulk’ formulations and are considered inert and harmless, but questions about the safety of their ‘nano’ formulations have been raised; they reportedly can cause adverse effects in living organisms, largely through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in cellular damage and possible genotoxicity and nanoparticle-sized titanium dioxide (nTiO2) has been classified as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” via inhalation (see Skocaj et al., 2011). Since so little is yet known about the effects, and there are problems with informed consent, monitoring and controlling the material after release to the public, and the proportionality of hazards versus benefits, Jacobs, van de Poel and Osseweijer (2010) have called the marketing of nTiO2 an ethically undesirable “social experiment.” In the marine environment, nTiO2 has been found to bioaccumulate in the gills and digestive glands of clams, suggesting “a potential risk for filter-feeding animals” (Ilaria, 2018). Both inorganic (titanium and zinc oxides) and various organic sunscreens have been found to have deleterious effects on phytoplankton, which carries out the preponderance of photosynthesis going on in the oceans and thus make up the base of virtually the entire oceanic food web (Tovar-Sanchez et al., 2013).