Digital Accessibility as a Business Practice by Digital Education Strategies, The Chang School is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Digital Accessibility as a Business Practice by Digital Education Strategies, The Chang School is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Most business leaders would agree that reaching the broadest audience is good for a business’s bottom line. A good portion of that audience will be people with disabilities. How, though, would an organization go about ensuring it is as accessible as it can be to all its potential clients or customers, including people with disabilities?

This resource has been created to answer this question and to demystify “digital accessibility” as a business practice. It brings together all the pieces of the digital accessibility picture and provides strategies and resources that will help make digital accessibility a part of an organization’s business culture.

This resource is an adaptation of the massive open online course (MOOC) of the same name, developed through The G. Raymond Chang School of Continuing Education at Ryerson University and offered through the Canvas Network. To see when the course will be offered next, check the course website.

Though the resource originates in Ontario, Canada, and includes some discussion of the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA), the content will be relevant to a global audience. Accessibility as it applies to AODA and Ontarians applies equally in other jurisdictions, albeit perhaps in some cases without the motivation of the law to enforce it as a requirement. Many are watching Ontario as it rolls out its 20-year plan to make the province the most accessible jurisdiction in the world.

Though the learning materials here are aimed at educating business leaders and managers about digital accessibility as a business practice, it will be of interest to anyone who wants to understand organizational culture in general and how digital accessibility fits into that culture. What you’ll learn here goes well beyond accommodating people with disabilities or adhering to the law. It is about improving your bottom line and ensuring your business or organization is able to serve its whole audience — not just those who are able bodied or using the latest technology, but also those from the margins of society, who are often overlooked by the mainstream. Being a good “corporate citizen” and “doing the right thing” are phrases often used to justify making an effort to remove potential barriers to goods and services, but it’s more than that.

The business arguments for accessibility are many. They are about reaching the broadest audience possible. People with disabilities have family and friends, who will go elsewhere if together they are unable to effectively access your business’s website or digital content. When you consider that people with disabilities make up nearly 15% of the population (WHO), and when you include their mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, and more, that number can reach 50% of the population who are affected by disability in one way or another. Most businesses would have a hard time justifying serving only 50% of their potential customer base.

The bottom line: Digital accessibility is good for business.

This resource has been made possible with the help of many others.

Funding for this project was provided by the Government of Ontario’s Enabling Change Program.

Human resources were provided by the Digital Education Strategies team at The G. Raymond Chang School for Continuing Education at Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada, including an instructional designer, web developer, and production editor. Contributors include:

Welcome to Digital Accessibility as a Business Practice. We are glad that you are learning about this important topic!

By the time you complete the instruction here, you should be able to:

(More specific learning objectives are included with each unit.)

There are no prerequisites to successfully learn from the materials provided here. However, basic familiarity with the principles of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.0) will be beneficial.

To learn more, read through the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines and the Introduction to WCAG.

You will need the following applications to apply the knowledge you’ll gain and to complete the activities:

The content here is made up of the introductory section that you are reading now, plus six units.

Throughout the units there are a number of short Challenge Tests that will help reinforce what you are learning. They are interactive, with instant feedback in the web ebook version, and with a text-based alternative and answer key in the other available formats.

Throughout the materials, a storyline about “The Sharp Clothing Company” will unfold, and as a project manager for the company, you will investigate what the company must do to create a “digital accessibility culture.” The company will be introduced in Unit 2, and the story will continue from there.

Throughout the materials, a storyline about “The Sharp Clothing Company” will unfold, and as a project manager for the company, you will investigate what the company must do to create a “digital accessibility culture.” The company will be introduced in Unit 2, and the story will continue from there.There are many Readings & References boxes mentioned throughout the units that expand on the content being presented. You are encouraged to explore these resources, but you will not be tested on them.

Readings & References:

For those who would like to go beyond what they’ve learned here, The Chang School offers additional resources on digital accessibility aimed at a variety of audiences.

The information presented here is for instructional purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice on any particular issue, including compliance with relevant laws. We specifically disclaim any liability for any loss or damage any participant may suffer as a result of the information contained. Furthermore, successful completion of activities contained here does not result in formal accreditation or recognition within or for any given field or purpose.

This unit is an orientation and provides the information you need to successfully learn from the instruction provided here. Though we do not talk about digital accessibility in this unit, it is still important to read through it.

This resource is aimed primarily at those who are responsible for implementing accessibility at an organizational level. These people tend to be managers, but may also be accessibility specialists, whose role it is to oversee the implementation of accessibility strategies and awareness throughout an organization.

Web developers may also wish to read the materials here to expand their understanding of the organizational aspects of implementing accessibility, thereby extending their role to that of an IT accessibility specialist, who is often the person to lead the implementation of accessibility culture in an organization.

While managers and web developers are the primary audience here, anyone who has an interest in the aspects of implementing accessibility culture in an organization will find the materials informative.

A variety of elements have been added throughout the materials here to aid your learning. These are described here.

Throughout the content, we’ve identified elements that should be added to the Accessibility Toolkit you will be assembling as you keep reading. These elements will include links to resource documents and online tools, as well as software or browser plugins that you may need to install or introduce to your staff. These will be identified in a green Toolkit box like the following:

Though the instruction here has been developed without much of the technical details of accessibility, there are places throughout the content where important technical information has been included. These details are contained in the blue Technical boxes. It’s a good idea for those managing web accessibility efforts to be aware of some key technical elements of implementing digital accessibility, so they understand what technical staff should know.

Important or notable information will be highlighted and labelled in Key Point boxes such as the one that follows. These will include “must know” information.

Try This boxes contain activities designed to get you thinking or to give you first-hand experience with something you’ve just read about.

These short tests are included throughout the units to help you reinforce what you are learning.

The Final Project is writing a digital accessibility policy. Copy the template of topics listed below and paste them into the policy document you will develop. As you progress through the materials here, the readings and activities will provide information that you can use to help write the content for the document.

A digital accessibility policy should be written as a guide or set of instructions that management and staff can refer to when they need to understand what they should be doing to meet the organization’s accessibility requirements.

The following is a list of potential sections for the policy document. You can start with these and make the following changes and additions: add or remove sections or subsections; provide text for each section explaining the what, how, and/or who the section of the policy applies to; and organize it in a coherent way.

Key Point:

Though we attempt to make all elements of this resource conform with international accessibility guidelines, we must acknowledge a few accessibility issues that are out of our control.

This unit provides an overview of elements in digital accessibility culture, as well as background information to provide context for what you will learn about in the units that follow. You will develop a big picture of digital accessibility culture. This knowledge will act as a framework in which you will assemble key materials and resources as you progress through the content.

In the following video from the Whitby Chamber of Commerce, four local Durham region and Toronto business owners tell us what accessibility means to their businesses. (Note: The captions for this video no longer seem to be working.)

Video: What does accessibility mean to your business?

© TheWhitbychamber. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

By the end of this unit, you should be able to:

By the end of this unit, you should be able to:

The narrative here revolves around the story of “The Sharp Clothing Company” who recently received a complaint about the accessibility of their online store, which included a threat to take legal action if the company does not address the issue in a reasonable amount of time. This complaint came as a surprise to the company, who thought they were compliant with local accessibility laws, having recently retrofitted several of their retail locations to accommodate wheelchair access. However, they did not consider digital accessibility.

The narrative here revolves around the story of “The Sharp Clothing Company” who recently received a complaint about the accessibility of their online store, which included a threat to take legal action if the company does not address the issue in a reasonable amount of time. This complaint came as a surprise to the company, who thought they were compliant with local accessibility laws, having recently retrofitted several of their retail locations to accommodate wheelchair access. However, they did not consider digital accessibility.

The company currently has twelve stores across Ontario and Quebec located primarily in shopping malls, and a distribution centre where clothing imported from around the world is distributed to physical stores and out to customers purchasing online. The head office is located in central Toronto.

The company has been growing rapidly, opening about two new stores per year since going public in 2012, with 222 people currently employed, across a broad range of roles. The company is making plans to expand into international markets in the coming year.

Total number of employees: 222

The complaint that was filed ended up with the company’s CEO. She has come to you to handle the issue and tasks you to ensure that this type of complaint does not happen again. You already have a little background in accessibility, but it is primarily around customer service and design of physical spaces to accommodate people with disabilities. You gained this experience as the project manager during the company’s efforts to make its stores accessible to people with disabilities. However, you have little experience with “digital accessibility” and have a limited technical background.

Your goal is to educate yourself about digital accessibility and implement a plan to address the complaint to ensure no other similar complaints occur. You have a budget which might cover hiring one or two additional staff members, training staff, updating technology, and launching promotional activities to raise awareness of digital accessibility throughout the company.

You will be working closely with other managers and specific staff in order to bring the company into compliance with digital accessibility laws, both locally and in the jurisdictions where the company is planning to do business.

As you progress through the reading and activities, you will be introduced to the various elements that need to be addressed in order to accomplish the company’s compliance goals. In the final unit, you will assemble what you have learned into a Digital Accessibility Policy for the Sharp Clothing Company, a document that you can take away and ultimately use as a guide to implementing an accessibility plan for your own organization.

In 2011 and 2012, Karl Groves wrote an interesting series of articles that looked at the reality of business arguments for web accessibility. He points out that any argument needs to answer affirmatively to at least one of the following questions:

He outlines a range of potential arguments for accessibility:

What accessibility really boils down to is “quality of work,” as Groves states. So, in approaching web accessibility, you may be better off not thinking so much in terms of reducing the risk of being sued, or losing customers because your site takes too long to load. Rather, the work you do is quality work, and the website you present to your potential customers is a quality website.

Video: The Business Case for Accessibility

Readings & References: If you’d like to learn more about business cases, here are a few references:

Video: AODA Background

For readers from Ontario, Canada, we’ll provide occasional references to the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA). If you’re studying here to work with accessibility outside Ontario, you may compare AODA’s web accessibility requirements with those in your local area. They will be similar in many cases and likely based on the W3C WCAG 2.0 guidelines. The goal in Ontario is for all obligated organizations to meet the Level AA accessibility requirements of WCAG 2.0 by 2021, which, ultimately, is the goal of most international jurisdictions.

The AODA provided the motivation to create this resource. All businesses and organizations in Ontario with more than 50 employees (and all public sector organizations) are now required by law to make their websites accessible to people with disabilities (currently Level A). Many businesses still don’t know what needs to be done in order to comply with the new rules, and this resource hopes to fill some of that need.

The AODA was passed as law in 2005, and, in July of 2011, the Integrated Accessibility Standards Regulation (IASR) brought together the five standards of the AODA, covering information and communication, employment, transportation, and design of public spaces, in addition to the original customer service standard.

The AODA sets out to make Ontario fully accessible by 2025, with an incremental roll-out of accessibility requirements over a period of 20 years. These requirements span a whole range of accessibility considerations, including physical spaces, customer service, the web, and much more.

Our focus here is on access to information, information technology (IT), and the web. The timeline set out in the AODA requires government and large organizations to remove all barriers in web content between 2012 and 2021. The timeline for these requirements is outlined in the table below. Any new or significantly updated information posted to the web must comply with the given level of accessibility by the given date. This includes both internet and intranet sites. Any content developed prior to January 1, 2012 is exempt.

| Level A | Level AA | |

|---|---|---|

| Government | January 1, 2012 (except live captions and audio description) | January 1, 2016 (except live captions and audio description) |

| January 1, 2020 (including live captions and audio description) | ||

| Designated Organizations* | Beginning January 1, 2014, new websites and significantly refreshed websites must meet Level A (except live captions and audio description) | January 1, 2021 (except live captions and audio description) |

| * Designated organizations means every municipality and every person or organization as outlined in the Public Service of Ontario Act 2006 Reg. 146/10, or private companies or organizations with 50 or more employees, in Ontario. | ||

Readings & References: For more about the AODA you can review the following references:

Video: AODA: IASR: Information and Communications

© Melanie Belletrutti. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

The Sharp Clothing Company recently completed upgrading all of its premises to include wheelchair access ramps, accessible washrooms, wheelchair-height customer service desks, and so on. The management was confident everything was done to meet accessibility standards, so they were surprised to receive a customer complaint about the company’s online store being completely inaccessible by keyboard.

The Sharp Clothing Company recently completed upgrading all of its premises to include wheelchair access ramps, accessible washrooms, wheelchair-height customer service desks, and so on. The management was confident everything was done to meet accessibility standards, so they were surprised to receive a customer complaint about the company’s online store being completely inaccessible by keyboard.

You have been asked to investigate the issue. After looking into the complaint you are surprised to find that there were many different types of disabilities and each one with its own accessibility challenges. You decide you need to learn more about how people with different disabilities use the web and digital information, since you see now there is more to accessibility than providing access for wheelchair users.

To understand where accessibility issues can arise, it is helpful to have a basic understanding of a range of disabilities and the related barriers found in digital content. These include:

Not all people with disabilities encounter barriers in digital content, and those with different types of disabilities encounter different types of barriers. For instance, if a person is in a wheelchair, they may encounter no barriers at all in digital content. A person who is blind will experience different barriers than a person with limited vision. Many of the barriers that people with disabilities encounter on the web are often barriers found in electronic documents and multimedia. Different types of disabilities and some of their commonly associated barriers are described here.

Watch the following video to see how students with disabilities experience the Internet.

Video: Experiences of Students with Disabilities

© Jared Smith. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

In this video, David Berman talks about types of disabilities and their associated barriers.

Video: Web Accessibility Matters: Difficulties and Technologies: Avoiding Tradeoffs

© davidbermancom. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

People who are blind tend to face the most barriers in digital content, given the visual nature of much digital content. They will often use a screen reader to access their computer or device, and may use a refreshable Braille display to convert text to Braille.

Common barriers for this group include:

For a quick look at how a person who is blind might use a screen reader like JAWS to navigate the web, watch the following video.

Video: Accessing the web using screen reading software

© rscnescotland. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

People with low vision are often able to see digital content if it is magnified. They may use a screen magnification program to increase the size and contrast of the content to make it more visible. They are less likely to use a screen reader than a person who is blind, though in some cases they will. People with low vision may rely on the magnification or text customization features in their web browser or word processor, or they may install other magnification or text reading software.

Common barriers for this group include:

See the following video for a description of some of the common barriers for people with low vision.

Video: Creating an accessible web (AD)

© Media Access Australia. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

Most people who are deaf tend to face barriers where audio content is presented without text-based alternatives, and encounter relatively few barriers in digital content otherwise. Those who are deaf and blind will face many more barriers, including those described for people who are blind. For those who communicate with American Sign Language (ASL) or other sign languages (e.g., langue de Signes Quebecoise or LSQ), the written language of a website may produce barriers similar to those faced when reading in a second language.

Common barriers for this group include:

Mobility-related disabilities are quite varied. As mentioned earlier, one could be limited to a wheelchair for getting around, and face no significant barriers in digital content. Those who have limited use of their hands or who have fine-motor impairments that limit their ability to target and click elements in digital content with a mouse pointer, may not use a mouse at all. Instead, they might rely on a keyboard or perhaps their voice to control movement (i.e., speech recognition) through digital content along with switches to control mouse clicks.

Common barriers for this group include:

Learning and cognitive-related disabilities can be as varied as mobility-related disabilities, perhaps more so. These disabilities can range from a mild reading related disability, to very severe cognitive impairments that may result in limited use of language and difficulty processing complex information. For most of the disabilities in this range, there are some common barriers, and others that only affect those with more severe cognitive disabilities.

Common barriers for this group include:

More specific disability-related issues include:

While we generally think of barriers in terms of access for people with disabilities, there are some barriers that impact all types of users, though these are often thought of in terms of usability. Usability and accessibility go hand-in-hand. Adding accessibility features improves usability for others. Many people, including those who do not consider themselves to have a specific disability (such as those over the age of 50) may find themselves experiencing typical age-related loss of sight, hearing, or cognitive ability. Those with varying levels of colour blindness may also fall into this group.

Some of these usability issues include:

Knowing the lengths your company recently went to to ensure physical accessibility at the storefront locations, you are eager to gain an understanding about how accessibility legislation may extend into the digital realm. The added risk of potential legal action and reference to a human rights violation in the complaint has drawn concern from the company’s leadership. They have asked you to investigate further into what legislation might already exist with reference to digital accessibility.

Knowing the lengths your company recently went to to ensure physical accessibility at the storefront locations, you are eager to gain an understanding about how accessibility legislation may extend into the digital realm. The added risk of potential legal action and reference to a human rights violation in the complaint has drawn concern from the company’s leadership. They have asked you to investigate further into what legislation might already exist with reference to digital accessibility.

You discover that, in fact, there is legislation in place in Ontario as part of the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA), specifically Section 12 and Section 14 that speak to digital accessibility, which cover accessible formats and web content, respectively. You see that, indeed, accessible websites are addressed in Section 14(4).

While you are reading about the AODA Information and Communications Standard, you remember the discussion at the last manager’s meeting, about the plan coming together that will see several new stores open over the next year, located in the United States, the European Union, and Australia. It occurs to you that these countries may have their own digital accessibility standards, and that you should look into those while learning about the local accessibility requirements.

The W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.0) has become broadly accepted as the definitive source for web accessibility rules around the world, with many jurisdictions adopting it verbatim, or with minor adjustments, as the basis for accessibility laws that remove discrimination against people with disabilities on the web.

While you do not need to read the whole WCAG 2.0 document, it is good to have a basic understanding of what it covers.

After reviewing the 10 Key Guidelines, start by learning about the Canadian and U.S. web accessibility regulations, then take the Challenge Test to check your knowledge.

The materials here haqve been written in the context of the AODA, which came into effect in 2005 with the goal of making Ontario the most inclusive jurisdiction in the world by 2025. Part of this twenty-year rollout involved educating businesses in Ontario, many of which are now obligated by the Act to make their websites accessible, first at Level A between 2012 and 2014, and at Level AA between 2016 and 2021.

Key Point: AODA adopts WCAG 2.0 for its Web accessibility requirements, with the exception of two guidelines:

Otherwise, AODA adopts WCAG 2.0 verbatim.

In 2011, the Government of Canada (GOC) introduced its most recent set of web accessibility standards, made up of four sub standards that replace the previous Common Look and Feel 2.0 standards. The Standard on Web Accessibility adopts WCAG 2.0 as its Web accessibility requirements with the exception of Guideline 1.4.5 Images of Text (Level AA) in cases where “essential images of text” are used, in cases where “demonstrably justified” exclusions are required, and for any archived Web content. The standard applies only to Government of Canada websites.

In 2014 the British Columbia government released Accessibility 2024, a ten-year action plan designed around twelve building blocks intended to make the province the most progressive in Canada for people with disabilities. Accessible Internet is one of those building blocks. The aim is to have all B.C. government websites meet WCAG 2.0 AA requirements by the end of 2016.

Currently a work in progress, this act intends to produce national accessibility regulations for Canada. Visit the Barrier-Free Canada website for more about the developing Canadians with Disabilities Act, and the Government of Canada on the consultation process.

The ADA does not have any specific technical requirements upon which it requires websites to be accessible, however, there have been a number of cases where organizations that are considered to be “places of public accommodation” have been sued due to the inaccessibility of their websites (e.g., Southwest Airlines and AOL), where the defendant organization was required to conform with WCAG 2.0 Level A and Level AA guidelines.

There is a proposed revision to Title III of the ADA (Federal Register Volume 75, Issue 142, July 26, 2010) that would, if passed, require WCAG 2.0 Level A and AA conformance to make Web content accessible under ADA.

Section 508 is part of the U.S. Rehabilitation Act and its purpose is to eliminate barriers in information technology, applying to all Federal Agencies that develop, procure, maintain, or use electronic and information technology. Any company that sells to the U.S. Government must also provide products and services that comply with the eleven accessibility guidelines Section 508 describes in Section 1194.22 of the Act.

These guidelines were originally based on a subset of the WCAG 1.0 guidelines, and were recently updated to include WCAG 2.0 Level A and AA guidelines as new requirements for those obligated through Section 508. Though in effect as of March 20, 2017, those affected by the regulation are required to comply with the updated regulation by January 18, 2018.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

http://pressbooks.library.ryerson.ca/dabp/?p=654

The Equality Act in the United Kingdom does not specifically address how web accessibility should be implemented, but in Section 29(1), require that those who sell or provide services to the public must not discriminate against any person requiring the service. Effectively, preventing a person with a disability from accessing a service on the web constitutes discrimination.

Sections 20 and 29(7) of the Act make it an ongoing duty of service providers to make “reasonable adjustments” to accommodate people with disabilities. To this end, the British Standards Institution (BSI) provides a code of practice (BS 8878) on web accessibility, based on WCAG 1.0.

For more about BSI efforts, watch the following video:

Video: BSI Documentary – Web accessibility – World Standards Day 14 Oct 2010

© BSI Group. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

Readings & References:

Throughout Europe, a number of countries have their own accessibility laws, each based on WCAG 2.0. In 2010, the European Union itself introduced web accessibility guidelines based on WCAG 2.0 Level AA requirements. The EU Parliament passed a law in 2014 that requires all public sector websites, and private sector websites that provide key public services, to conform with WCAG 2.0 Level AA requirements, with new content conforming within one year, existing content conforming within three years, and multimedia content conforming within five years.

This does not mean, however, that all countries in the EU must now conform. The law now goes before the EU Council, where heads of state will debate it, which promises to draw out adoption for many years into the future, if it gets adopted at all.

Readings & References:

In Italy, the Stanca Act 2004 (Disposizioni per favorire l’accesso dei soggetti disabili agli strumenti informatici) governs web accessibility requirements for all levels of government, private firms that are licensees of public services, public assistance and rehabilitation agencies, transport and telecommunications companies, as well as ICT service contractors.

The Stanca Act has 22 technical accessibility requirements originally based on WCAG 1.0 Level A guidelines, updated in 2013 to reflect changes in WCAG 2.0.

Readings & References:

In Germany, BITV 2.0 (Barrierefreie Informationstechnik-Verordnung), which adopts WCAG 2.0 with a few modifications, requires accessibility for all government websites at Level AA (i.e., BITV Priority 1).

Readings & References:

Accessibility requirements in France are specified in Law No 2005-102, Article 47, and its associated technical requirements are defined in RGAA 3 (based on WCAG 2.0). It is mandatory for all public online communication services, public institutions, and the State, to conform with RGAA (WCAG 2.0).

Readings & References:

The web accessibility laws in Spain are Law 34/2002 and Law 51/2003, which require all government websites to conform with WCAG 1.0 Priority 2 guidelines. More recently, UNE 139803:2012 adopts WCAG 2.0 requirements and mandates that the following types of organizations comply with WCAG Level AA requirements: government and government-funded organizations; organizations larger than 100 employees; organizations with a trading column greater than 6 million Euros; or organizations providing financial, utility, travel/passenger, or retail services online.

(See: Legislation in Spain )

Readings & References:

Though not specifically referencing the web, section 24 of the Disability Discrimination Act of 1992 makes it unlawful for a person who provides goods, facilities, or services to discriminate on the grounds of disability. This law was tested in 2000, when a blind man successfully sued the Sydney Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (SOCOG) when its website prevented him from purchasing event tickets.

The Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) shortly after released the World Wide Web Access: Disability Discrimination Act Advisory Notes. These were last updated in 2014, and, while they do not have direct legal force, they do provide web accessibility guidance for Australians on how to avoid discriminatory practices when developing web content, based on WCAG 2.0.

Readings & References:

Readings & References: For more about international web accessibility laws, see the following resources:

Establishing a culture of accessibility in an organization requires buy-in from senior management. These managers may not always understand the implications of accessibility barriers on the company. Using the knowledge you have gained to this point, write an elevator pitch to convince a senior manager that accessibility is important to the company.

Establishing a culture of accessibility in an organization requires buy-in from senior management. These managers may not always understand the implications of accessibility barriers on the company. Using the knowledge you have gained to this point, write an elevator pitch to convince a senior manager that accessibility is important to the company.

If you are not familiar with elevator pitches, they often unfold when you, the speaker, getting on the elevator, happen to run into a key senior person in the company, who typically spends her day running from meeting to meeting. You have her as a captive audience for one minute while the elevator ascends. This is the only opportunity you will have to pitch your idea to this person, and if you succeed in convincing this person, she will support you in your effort.

Your task in this activity is to convince one of the following people that digital accessibility is very important and you have a good idea that is sure to benefit the company. You may want to consider different arguments to convince different people.

For help with creating your elevator pitch, read Mindtools’s How to Create an Elevator Pitch.

Suggested Viewing: If you would like to see examples of an elevator pitch, have a look through the following video resources.

1. Video: 6 Elevator Pitches for the 21st Century

© THNKR. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

2. Video: Elevator Pitch Winner (Utah State)

© UtahStateCES. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

3. Video: Sarah Bourne Makes the Business Case for Implementing Accessible Technology

© PEATworks. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

4. Video: Mike Paciello Makes the Business Case for Implementing Accessible Technology

© PEATworks. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

In this unit, you learned that:

In this unit, you learned that:

If your organization has more than a handful of employees, or has multiple groups or departments that serve different purposes within the organization, it is helpful to recruit staff to represent and speak for each group on an Accessibility Committee (or whatever you choose to call it). These will typically be comprised of people in senior positions, people with influence, and employees with disabilities. These committee members must be willing to sell the ideas put forth by the committee to raise awareness and affect the culture within the group they represent.

You will probably also want to assign a person to be in charge of the whole committee: A person we will refer to as the Accessibility Champion. This person should have expertise in the accessibility area, be able to lead, manage change, and oversee the organization’s accessibility efforts as a whole.

By the end of this unit, you should be able to:

By the end of this unit, you should be able to:

Having learned about how people with disabilities use digital content and the Web, and knowing about the local and international digital accessibility regulations, you now want to determine what led to the customer’s complaint in the first place.

Having learned about how people with disabilities use digital content and the Web, and knowing about the local and international digital accessibility regulations, you now want to determine what led to the customer’s complaint in the first place.

The person who submitted the complaint has identified that he is blind and uses a technology called a screen reader to access content on the Web. From your research on how people with disabilities use the Web, you know that screen readers read out the text content from web pages.

The complaint mentions two particular issues. First, many images in the shopping area of the company’s website are announced as file names, such as “rt-004.jpg”, rather than something meaningful like “add to shopping cart.” You discover the problem is the result of images in the shopping cart application not having a text description. You know that “alt text” is the way to provide a text description for images on the Web.

Second, the buttons in the shopping cart cannot be activated with a key press; rather, they require a person to click the buttons with a mouse. Since people who are blind typically cannot use a mouse (not being able to see a mouse pointer), you have learned that they usually rely on their keyboard to navigate through content and to press buttons or activate links. When these website elements cannot be accessed or operated with a key press, they are inaccessible to anyone who relies on a keyboard to navigate.

You first approach the content developer who set up the products in the shopping cart application, and ask that she go through the product list and add the missing text descriptions. But, she tells you the shopping cart editor does not have a way to add text descriptions, or alt text, for product images.

You then approach your company’s web developer to see if it is possible to add an alt text field to the editor used to add product images. As it turns out, the shopping cart application is a third-party proprietary application, and, apart from simple changes to brand the shopping cart, there is little that can be done to make changes to the editor without going back to the vendor. You also ask your web developer about the keyboard access problem, and he tells you this cannot be modified either without going back to the vendor.

You wonder how the company ended up purchasing this shopping cart application given its limited accessibility support. The next stop in your investigation is your purchasing department. You ask about the accessibility requirements that were included with the request for proposals (RFP), and discover that no accessibility requirements were outlined in the RFP. The purchasing department did not know about the requirement to purchase accessible technologies when they are available.

Through this investigation, you begin to realize that accessibility knowledge needs to be weaved through many roles in the company. The next area you focus on is understanding what types of digital accessibility knowledge is needed for various roles in the company, and the potential training that might be needed to ensure various roles understand their accessibility responsibilities.

The roles you identify include:

Depending on a person’s role in a company, different types of accessibility knowledge may be needed. The following is an example of the different knowledge various roles may need, though depending on the size of a company and the nature of the business, this knowledge could be adapted across roles. For instance, if a company does not have a human resource (HR) department, then knowledge of accessible hiring practices and accessibility knowledge requirements for various roles may shift to senior managers responsible for hiring new staff.

Retail store staff: Since retail staff often do not use digital tools or content beyond perhaps a web-based checkout, the main focus of their knowledge should be disability sensitivity, so they are able to interact comfortably and appropriately when people with disabilities are shopping in the retail stores.

People are often unsure how to interact with a person with a disability, if they have little experience with it. They may feel uncomfortable and wary of saying the wrong thing. In general, people with disabilities should be treated like anyone else, though this may be difficult for some, for instance, who have never met a person who is blind or deaf or uses a wheelchair.

Retail store managers and assistant managers: Like other retail store staff, store managers should also receive disability sensitivity training, and they should be able to provide training to other store staff.

Managers should also have a general overview of the business’s accessibility requirements as a whole, so they are able to identify and potentially resolve any accessibility issues they may encounter through the day-to-day retail store operation.

Web developers: The company’s web developers play a key role in ensuring that the company’s public website, in particular, meets accessibility requirements. They should have a good understanding of the W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.0), in addition to having expert knowledge of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. WCAG is the international guideline for developing accessible web content and is the basis for many international web accessibility regulations.

A web developer may also be a good person to oversee the company’s digital accessibility efforts, as they have a good understanding of the technologies involved and the ability to evaluate and remediate accessibility issues. An accessibility lead should have both understanding of accessibility technology, and an understanding of disability and related accessibility barriers. This combination of expertise can be difficult to find, so it would be more effective to educate a web developer on disability and accessibility issues than training a disability expert on the technical aspects of implementing digital accessibility.

Web content editors: Those who develop the content for a website should have basic understanding of WCAG 2.0, though they typically do not need the level of understanding that web developers need. Among the many potential accessibility issues in digital content, web content editors should be aware of things like including text descriptions for images, structuring content with the proper use of headings, and creating links in content that describe in a meaningful way where the link leads.

Communications and marketing staff: Marketing staff should also have the basic understanding of WCAG that content editors have, though there are some other guidelines that may be relevant, such as effective use of colour when developing promotional materials (e.g., having sufficient contrast between foreground and background and ensuring that colour alone is not used to represent meaning).

Marketing staff may also produce documents that are distributed both internally and externally to the public. They should also have an understanding of how to use accessibility features in various document authoring tools such as Microsoft Word or Adobe Acrobat Pro, among others. Most current document authoring tools should have features for testing and authoring accessible documents. Upgrades may be necessary to take advantage of those features, if older software is still being used.

Procurement and purchasing staff: Those who buy products and resources for a company need to have a good understanding of WCAG 2.0, or at a minimum understand that when purchasing, software in particular, and choosing between comparable products, the more accessible one should be purchased. Purchasing agents may make use of third party accessibility evaluation services to report on the accessibility of potential purchases. The company’s web developers may also be a good source for evaluators, assuming they have acquired the necessary expertise with WCAG.

Procurement staff also need to know how to ask for accessibility features from vendors and how to critically evaluate the responses to those requests, ensuring vendors are being honest about the accessibility of their products. Some vendors may tell you what you want to hear, which may not necessarily be the whole truth, while others may not know about accessibility, which is a good indication that there products are not accessible.

Telephone support staff: These staff should have similar disability sensitivity training, though typically, unless a person identifies themselves as having a disability, they may not be aware of such facts. Nonetheless, if they are interacting with a person they know to have a disability, they need to know how to interact in an acceptable way.

Telephone support staff should know how to use a TTY (Teletype or Teletypewriter), used by people who are deaf to communicate with hearing individuals by phone. If your support services do not include TTY access, telecommunications providers can typically provide the service.

Video support staff: Video production editors need to know about captioning and audio description. Captioning provides access to the audio track in multimedia content for those who are deaf, and audio description provides access to meaningful visual elements or activity in a video that are not obvious by listening to the audio track, for those who are blind.

Graphic artists: Similar to marketing staff, graphic artists need to be aware of the basic WCAG guidelines and issues around the use of colour.

Senior managers and directors: The senior people in a company need to have a basic understanding of digital accessibility as a whole, as well as a good understanding of the accessibility regulations that govern a business’s accessibility requirements. They also need to be open to change and to understand the business arguments for creating an inclusive business. Ultimately, it is the senior management in a company that make or break a company’s accessibility efforts.

Human resource staff: HR staff need to have a good understanding of the local accessibility laws, and related accessible hiring practices. They also need to know about the required accessibility knowledge for the roles described here, as well as other potential roles. HR staff also need to be able to ask the right questions to determine, for instance, if a web developer has expertise with WCAG, or to perhaps assess the marketing department or office personnel’s understanding of accessibility features in the authoring tools they use.

HR staff may also be responsible for training efforts. While having accessibility knowledge for a given role should give applicants an advantage over others, in reality it is often difficult to find candidates with both expert understanding of the job they are being hired for, and knowledge of accessibility elements for that role. Fortunately, for many roles, accessibility training is often quick, like training office staff to use PDF accessibility features. With a few hours of training, staff can acquire all the skills they need to get started creating accessible content. However, for other roles, like web developers, it can take a significant amount of training and time to develop their expertise.

Distribution centre staff: These staff members may need little accessibility training. These people may include inventory control staff, a shipper/receiver, truck drivers, or a warehouse manager, among others. They may have no interaction with the public, and may not be involved in activities that produce digital content, but should be aware of their company’s accessibility obligations.

Office support staff: These staff members are likely to use various document authoring tools, and should be aware of, and use, the accessibility features tools such as Microsoft Word and Acrobat Acrobat Pro provide.

Understanding the diversity of skills and knowledge in the company’s workforce, you decide that it will be more effective if each department managed their own digital accessibility efforts. You decide to create an accessibility committee, made up of senior or influential people from each of the major groups in the company. Your goal is to take a proactive approach to accessibility, addressing issues before they become complaints, rather than a reactive approach, where issues are addressed only when a complaint has been received.

Understanding the diversity of skills and knowledge in the company’s workforce, you decide that it will be more effective if each department managed their own digital accessibility efforts. You decide to create an accessibility committee, made up of senior or influential people from each of the major groups in the company. Your goal is to take a proactive approach to accessibility, addressing issues before they become complaints, rather than a reactive approach, where issues are addressed only when a complaint has been received.

By implementing a proactive approach, you are aiming to address potential barriers before they result in lost customers. While the company did receive a complaint, you understand that many people who encounter accessibility barriers do not complain. They just leave, perhaps going to the competition. You are convinced that if they come to your website and have a pleasant, accessible experience, they will likely return and make additional purchases.

You plan to have the accessibility committee initially meet several times over a two month period, to get accessibility efforts underway, then reduce the frequency of meetings to once per quarter, to receive updates from each group and discuss any new issues that arise.

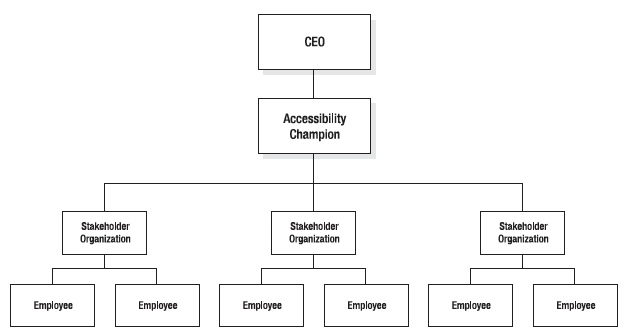

Ideally the Accessibility Committee (AC) should be made up of influential and knowledgeable representatives from different areas of the company, starting with a senior executive who can affect the company’s accessibility policy. In Figure 2.1, the CEO at the top of the organizational structure would be that person, though it does not necessarily need to be the company’s top officer.

Below the senior executive is the person who will oversee the committee, in this case referred to as the “Accessibility Champion.” This person should be in a relatively senior position, or have substantial influence in the company, who has a good understanding of accessibility, disability, and the technical aspects of implementing accessibility. This person should also find accessibility interesting and challenging, and should not be forced into the role. Depending on the size of the company, it may be a person dedicated specifically to overseeing the company’s accessibility efforts, or it could be someone in another role who manages accessibility efforts on a part-time basis.

You debate whether you are the best person to take on the Accessibility Champion role. While you are becoming more familiar with digital accessibility, and you find it very interesting, you are not sure if you have the technical knowledge to fully understand the possibilities or options for developing and implementing digital accessibility. For now, you take on the role yourself, but leave the option open to assign the role to another member of the accessibility committee once it has been established, or even look outside the company for a person with the right balance of technical background and disability/accessibility knowledge to understand the technologies involved.

You debate whether you are the best person to take on the Accessibility Champion role. While you are becoming more familiar with digital accessibility, and you find it very interesting, you are not sure if you have the technical knowledge to fully understand the possibilities or options for developing and implementing digital accessibility. For now, you take on the role yourself, but leave the option open to assign the role to another member of the accessibility committee once it has been established, or even look outside the company for a person with the right balance of technical background and disability/accessibility knowledge to understand the technologies involved.

You decide to approach the CEO, who originally asked you to investigate the complaint, and ask her if she would be a member of the committee. She agrees, but suggests that after initially establishing the committee, she will pass that role to the senior VP. You also approach the director of retail sales, who oversees the retail managers and visits retail stores regularly. You also ask the IT manager to participate, as well as one of the senior web developers who reports to him and who has some web accessibility experience.

Other members of the accessibility committee are strategically selected from throughout the company, with the aim of including representatives across all areas of the company where digital accessibility is a concern, as well as those known to be knowledgeable on the subject of digital accessibility, which may include people within the company who have disabilities.

Clear goals for the accessibility committee should be defined and promoted throughout an organization so that everyone understands the committee’s function.

The accessibility committee should be responsible for:

Source: Implementing Accessibility in the Enterprise, pp. 73-74

Readings & References:

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

http://pressbooks.library.ryerson.ca/dabp/?p=677

The Accessibility Champion will be the person who leads an organization’s accessibility efforts. The title may vary from organization to organization, though the role will be the same.

The Accessibility Champion should be able to relate to others at their level. For instance, when working with developers to promote accessibility practices, being able to talk to them with appropriate technical language will help get the message across convincingly. Similarly, when working with designers, this person should be able to talk in terms of Universal Design and Inclusive Design practices.

Though an Accessibility Champion does not necessarily need to have formal computer science or design backgrounds, knowledge in these areas is important to be effective in the role. At a minimum, the Champion needs to be comfortable working with technology, and have a good understanding of how people with disabilities access information and digital content.

The Accessibility Champion should have a particular set of necessary, and desirable characteristics, described here:

Playing the role of the Digital Accessibility Project Manager, one of your decisions will be who takes on the role of the Accessibility Champion. You could very well be the Champion, but do you have the characteristics to take on this role?

Playing the role of the Digital Accessibility Project Manager, one of your decisions will be who takes on the role of the Accessibility Champion. You could very well be the Champion, but do you have the characteristics to take on this role?

Using the “Characteristics of a Digital Accessibility Champion,” how many of the characteristics do you possess? How many are you lacking? What skills could you learn to make you better suited for the role? Are there other characteristics of a champion you have that are not mentioned?

In this unit, you learned that:

In this unit, you learned that:

“Culture,” in the context of digital accessibility, refers to an overarching consciousness or awareness throughout an organization of potential barriers — barriers that may prevent people with disabilities from participating in digital activities or consuming digital information at the same level as their fully able peers.

It means that attention to accessibility is weaved into an organization’s processes and integrated with quality assurance, so, when products and services are evaluated, accessibility is part of that evaluation. Everyone who is involved in producing products or delivering services has accessibility in mind while they carry out their duties. They know how to address accessibility in their work, and, if they encounter potential barriers they are not sure of, they ask questions, perhaps, addressing questions to accessibility experts on staff or to the Web or third-party experts to search out answers. In short, they will persevere until they find a solution.

Developing digital accessibility culture requires buy-in from the most senior executive in an organization. That buy-in trickles down through an organization, influencing senior managers, who influence junior managers, who influence the staff reporting to them, and so on, flowing all the way down the organizational hierarchy.

This culture, by way of its adoption throughout an organization, becomes a practice that guides business activities in designing and developing new products, to production, to service delivery, to marketing and communications, to procurement, to hiring, and more. All aspects of the organization are influenced by attention to digital accessibility inclusion.

By the end of this unit, you should be able to:

By the end of this unit, you should be able to:

One of the the accessibility committee’s first tasks is to determine where the company is in terms of its compliance with accessibility guidelines and to identify gaps where improvements are needed. Since you do not have an accessibility expert on staff, you decide to look into firms that provide accessibility auditing services.

One of the the accessibility committee’s first tasks is to determine where the company is in terms of its compliance with accessibility guidelines and to identify gaps where improvements are needed. Since you do not have an accessibility expert on staff, you decide to look into firms that provide accessibility auditing services.

Unless there is already an accessibility expert on staff, organizations likely want to hire a third-party auditor or find a person to hire on as one.

It is typically easier to find an auditing service than to find an accessibility expert to hire. Depending on the size of the company, and the amount of digital information it produces, you may or may not want to hire a permanent accessibility person.

Finding a reputable auditing service can also be a challenge. With the growing public awareness of accessibility issues, there are a growing number of so-called accessibility experts popping up, taking advantage of the market for these services that has emerged with this awareness. You want to evaluate these auditor services to ensure their reputability.

Factors you might take into consideration when selecting an accessibility service could include:

There are a number of reputable international services, so companies do not necessarily need to choose a local auditor. Since most accessibility regulations are based on WCAG, most international and local services audit based on those guidelines (or they should).

While searching for an accessibility-auditing firm on the Web, you come across a few accessibility-testing tools. Before you decide whether you need a third-party accessibility auditing service, you want to understand what you can do yourself with these tools to get a general sense of your company’s accessibility status. You decide to do a little research on tools that can be used to test/check accessibility. You find there are a wide variety of free and commercial accessibility-testing tools.

While searching for an accessibility-auditing firm on the Web, you come across a few accessibility-testing tools. Before you decide whether you need a third-party accessibility auditing service, you want to understand what you can do yourself with these tools to get a general sense of your company’s accessibility status. You decide to do a little research on tools that can be used to test/check accessibility. You find there are a wide variety of free and commercial accessibility-testing tools.There are quite a number of automated tools for testing web accessibility with varying degrees of coverage and accuracy. Much like choosing an accessibility auditor, choosing a good testing tool also requires a little critical evaluation. You may refer to existing evaluations of these tools and choose based on your needs. You may also want to adopt a number of accessibility checkers that complement each other.

Keep in mind that no automated accessibility checker can identify all potential barriers. In most cases, some human decision-making is required, particularly where meaning is being assessed. For example, does an image’s text alternative describe an image accurately, or does link text effectively describe the destination of the link? Both require a human decision on the meaningfulness of the text.

There a number of different types of web accessibility checkers. Depending on your needs, one type may serve your organization better than others.

API stands for application programming interface. An API allows developers to integrate the accessibility checker into other web-based applications, such as web-content editors, to provide accessibility testing from within the application. For instance, with a content editor, the checker assesses the contents of the editor while creating and editing content. Tenon and AChecker provide APIs that can be used for integrations with other applications. To take advantage of an API, a developer would need to create the integration in many cases, though some applications may already have an integration with an accessibility checker.

Text-based checkers typically output a list of accessibility issues it has identified; and, in some cases, provide recommendations to correct those issues. Some checkers may also categorize issues based on their importance or whether an issue is either a definite barrier or a potential barrier, which would need to be confirmed by a person. Some checkers evaluate single pages while others spider through a site and produce a site-wide accessibility report. These checkers often ingest one of the following: a URL of a web page, a user-uploaded HTML file, or copied and pasted HTML code; then, they produce a report based on the input provided. AChecker is a good example of a text-based accessibility checker, which also provides an API for integrations.

A third type of accessibility checker provides a visual presentation of a web page, pointing out where the issues appear on a page. The WAVE accessibility checker is a good example of a visual accessibility checker.

Some accessibility checkers are available as a browser plugin, making it easy, while viewing a web page, to click a button and get an accessibility report. The WAVE Chrome Extension is a good example of a browser-based plugin.

The accessibility checkers mentioned above are just a tiny sample of the tools available. A well-crafted Google search, using terms like “accessibility checker” turns up many more. Or, you can browse through the list of accessibility checkers compiled by the W3C at the following link.

While using automated web-accessibility checkers is a good start for assessing the accessibility of an organization’s web resources, there are likely other tools needed to assess different types of content. Examples of such tools include:

As mentioned above, automated testing cannot identify all potential accessibility barriers. There are a few easy manual tests that can be used to identify issues automated checkers may not pick up.

Understanding now that there are gaps in the company’s compliance with accessibility guidelines, you start to think about the approaches you might take to implement solutions to fill those gaps.

Understanding now that there are gaps in the company’s compliance with accessibility guidelines, you start to think about the approaches you might take to implement solutions to fill those gaps.

Having spent some time learning about accessibility testing and trying the tools and strategies you came across, you discover there are lots of potential accessibility problems with the company’s website. You share the results of your testing, and the tools and strategies with your senior web developer, who you ask to review and come up with an estimate of the time it would take to fix the issues you discovered.

The web developer reports back to you after a few days with a plan that will take longer than you expected. But, he also suggests, having reviewed the details of WCAG and the local accessibility regulations, perhaps he could prioritize the issues by first addressing the critical Level A issues described in WCAG, as well as addressing some of the easier Level AA issues.

He also suggests that you go back to the shopping cart vendor and see whether they are open to making some changes to their system to improve accessibility, reviewing the relevant business arguments if necessary in order to convince them the work will be good for their business.

Retrofitting an inaccessible website can be time consuming and expensive, particularly when the changes need to be made by someone other than the website’s original developer. Adding accessibility to a new development project will require much less effort and expense, assuming the developers have accessibility forefront in their mind while development is taking place.

Sometimes retrofitting is the only solution available. For instance, a company is not prepared to replace its website with a new one. In such cases, it may be necessary to prioritize what gets fixed first and what can be resolved later. WCAG can help with this prioritizing. It categorizes accessibility guidelines by their relative impact on users with disabilities, ranging from Level A (serious problems) to Level AAA (relatively minor usability problems). These levels are described below.

Level AA is the generally agreed-upon level most organizations should aim to meet, while addressing any Level AAA requirements that can be resolved with minimal effort. For organizations that directly serve people with disabilities, they may want to address more Level AAA issues, though it should be noted that full compliance with Level AAA requirements is generally unattainable, and in some cases undesirable. For instance, the WCAG lower-level high school reading level requirement is a Level AAA requirement. For a site that caters to lawyers, or perhaps engineers, high school-level language may be inappropriate, or even impossible, thus it would be undesirable to meet this guideline in such a case.

It is not uncommon for vendors, particularly those from jurisdictions that have minimal or no accessibility requirements, to resist an organization’s requests to improve accessibility of their products. But, there are also vendors who will jump at an opportunity to take advantage of an organization’s accessibility expertise to improve their product. The latter mentality is becoming more and more common as accessibility awareness grows around the world.

You realize that replacing the shopping cart on the company’s website, which was the subject of the complaint the company received, is not currently an option. The company has just renewed a three-year contract with the shopping cart provider and breaking that contract would be very costly. You understand that local regulations allow “undue hardship” as a legitimate argument for not implementing accessibility, and the company’s lawyer agrees.

You realize that replacing the shopping cart on the company’s website, which was the subject of the complaint the company received, is not currently an option. The company has just renewed a three-year contract with the shopping cart provider and breaking that contract would be very costly. You understand that local regulations allow “undue hardship” as a legitimate argument for not implementing accessibility, and the company’s lawyer agrees.

Regardless, you also understand that your company is losing a potentially large number of customers, who leave the website and shop elsewhere when they encounter accessibility barriers. You want to demonstrate that the company takes accessibility complaints seriously, so you approach the shopping cart vendor with a proposal to help them improve the accessibility of their product.

Depending on the vendor, various approaches may be taken to either guide the vendor through the process of addressing accessibility in their products, or convince a vendor that this is something they need to do.

Ideally, you want the collaboration with a vendor to be a collegial one, where both your company and the vendor are benefiting. You could offer to have an accessibility audit performed on the software being (or having been) purchased, which should have been done anyway as part of the procurement process, and offer that audit to the company. Contributing to a vendor in this way may create a sense of “owing your company” and they will be more receptive to working together to address accessibility issues. When purchasing a new product, it is often possible to have the vendor cover the cost of an accessibility audit performed by an auditor of the company’s choice. After the fact though, it’s unlikely a vendor will want to take on that expense. Thus, an audit may be more of an offering to keep the vendor on the side of the company when asking for work from them that will likely be unpaid.

On the other hand, if a vendor is resistant, and not interested in your offer, as a last resort you may need to apply more cunning tactics, for instance, by threatening to publish the accessibility audit.

Of course, these scenarios describe only a couple potential vendor/client relationships, which really require a clear understanding of a vendor’s position before approaching them with work they will likely not be paid for. Often the business arguments, introduced earlier, work well to convince vendors that accessibility is something that they can benefit from.

The bottom line is that some vendors will be more approachable than others and different strategies may be needed to have your accessibility requirements met by what may be considerable effort on the part of the vendor.

Suggested Viewing:

Video: Integrating Accessibility and Design: Five Hot Tips for Start-ups (Jutta Treviranus)

© MaRS Entrepreneurship Programs. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

Video: An Introduction to Digital Accessibility

© Tinmouse Animation Studio. Released under the terms of a Standard YouTube License. All rights reserved.

The initial goals reached by the accessibility committee through its first few meetings are to create an “accessibility culture” where the whole company is aware of the importance of accessibility, creating a policy that guides how digital accessibility is addressed throughout the company.

The initial goals reached by the accessibility committee through its first few meetings are to create an “accessibility culture” where the whole company is aware of the importance of accessibility, creating a policy that guides how digital accessibility is addressed throughout the company.

With a number of gaps identified, the committee suggests several initial areas to focus on, which together will provide the basis for the company’s accessibility policy.

One of the main reasons barriers arise is a lack of awareness. Most people have never met a person who is blind, let alone get to know such a person. As a result, they have little reason to think about accessibility and the potential barriers that may prevent a blind person from accessing digital content.

One sure way to raise awareness of accessibility is to hire people with a disability. Having people with disabilities in a company’s workforce helps build diversity, spread tolerance, and raise awareness of inequalities that are created when people have little or no experience with disability.

Hiring a person who is blind, for instance, will help expose your workforce to the challenges a blind person faces in everyday life and at work. This person could be a member of the accessibility committee, providing valuable input based on firsthand experience. This person could also provide screen reader testing of the company’s digital resources and quickly identify accessibility issues before they become complaints.

People who are blind can be just as skilled at many activities as people who can see. There are blind programmers, accountants, teachers, lawyers, even hairstylists, to name just a few occupations. Many are highly educated with advanced degrees and doctorates.

Blindness is used here as an example because this group tends to face the most barriers in digital content. However, many people with disabilities are skilled workers. They are often overlooked as a result of systemic misconception of what people with disabilities are capable of.

Accessibility awareness campaigns can take a variety of forms and can involve publicity, training opportunities, presentations, an archive of resource materials, and an initiative for more company staff. Depending on the size and type of business, some of the following strategies could be used to implement an awareness campaign:

Posters can be placed in prominent places where staff are likely to encounter them. Some of these locations may include elevators, printer and copier rooms, lunch rooms, reception areas, and bathrooms. Posters could also be made available through an archive linked from the company’s website, where accessibility resources are gathered.

Here is a sample of the types of posters that might be used in an accessibility awareness campaign: Accessible PDFs [PDF]

Instructional materials can also be created or gathered and added to the accessibility resources. Here are a few examples of the types of instructional materials that could be distributed:

Instructional videos can also be created, or gathered, and made available to staff. There are a great many videos from sources like YouTube that can be gathered into a single, easily accessible location, then publicized throughout the organization. Here are some examples of accessibility-related instructional videos. Search YouTube for more.

Email campaigns can also be another effective way to raise awareness, perhaps as part of a company newsletter include an “Accessibility Awareness” section. This section might include a link to video tutorials, perhaps updated from accessibility efforts ongoing throughout the company, links to various resources, or announcements about upcoming accessibility workshops. The possibilities are many, and, because a newsletter is distributed regularly, staff are consistently reminded of their accessibility responsibilities.

Or, you could set up a company mailing list, that anyone with an accessibility question can post to, as well as posting accessibility-related information similar to a newsletter. A person or two from the company’s accessibility committee could be assigned to monitor the mailing list and provide responses when others have not replied. All employees can be added to the mailing list, so everyone becomes aware of ongoing accessibility efforts, and receive regular “reminders” through the dialog occurring there.

Educating staff and teaching them new accessibility-related skills can help raise awareness throughout an organization. You may make workshops mandatory for particular staff, like web developers, or optional with a little bribery, like a pizza lunch, to get staff in the same room for a presentation and a question-and-answer session.

Providing an on-demand collection of resources related to accessibility and encouraging employees to use them can also help raise awareness. A knowledge base can be created with various types of educational materials, such as printable how-to tutorials, video, and examples of good practices. Employees should be encouraged to use these resources and contribute their own accessibility solutions. New additions to the knowledge base, or simply reminders to use what’s there, can be encouraged through the company newsletter, or perhaps with a prominent link on the company’s employee portal.

Your accessibility resources are beginning to accumulate. You’ve decided to put up a few posters and add an accessibility awareness section to your company’s monthly newsletter.

Your accessibility resources are beginning to accumulate. You’ve decided to put up a few posters and add an accessibility awareness section to your company’s monthly newsletter.